Commentary: Happy Birthday, Medicaid! Program Plays Key Role in People’s Health and Well-Being

End Notes

[1] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), March 2023 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html; Colleen M. Grogan and Sunggeun Ethan Park, “The Politics of Medicaid: Most Americans Are Connected to the Program, Support Its Expansion, and Do Not View It as Stigmatizing,” Millbank Quarterly, December 2017, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29226447/.

[2] KFF, “5 Charts about Public Opinion on Medicaid,” March 30, 2023, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/poll-finding/5-charts-about-public-opinion-on-medicaid/.

[3] Ibid.; Memo from Geoff Garin and Guy Molyneux, Hart Research Associates, to Protect Our Care, February 28, 2023, https://www.protectourcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Hart-Research-Fighting-Republican-Cuts-to-Medicaid-and-the-ACA.pdf.

[4] Jennifer Tolbert and Meghana Ammula, “10 Things to Know About the Unwinding of the Medicaid Continuous Enrollment Provision,” KFF, June 9, 2023, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/10-things-to-know-about-the-unwinding-of-the-medicaid-continuous-enrollment-provision/#three.

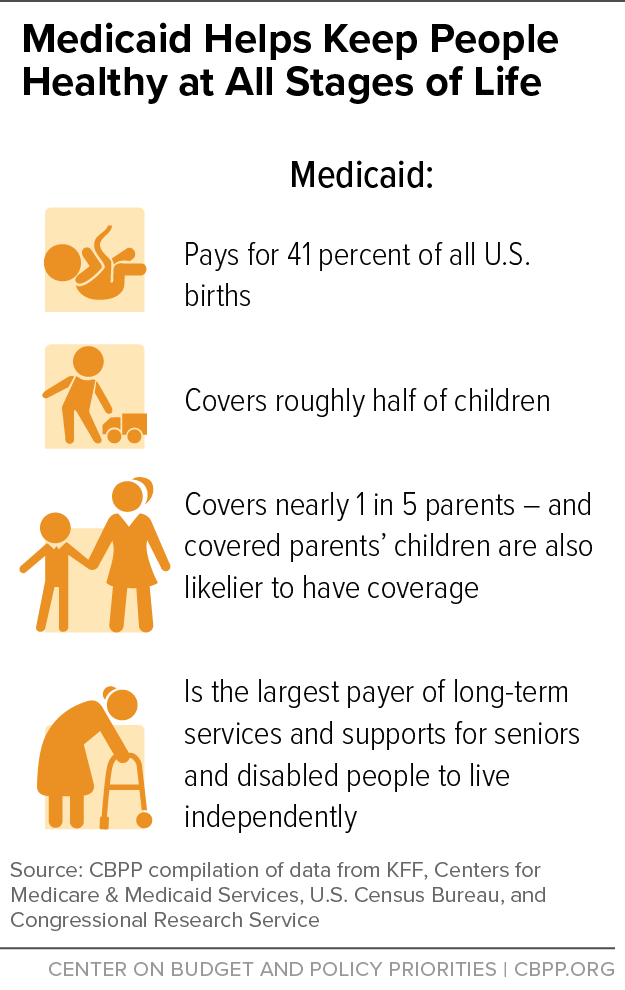

[5] KFF, Births Financed by Medicaid, 2021, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/births-financed-by-medicaid/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D; CMS, op. cit.; U.S. Census Bureau, National Population by Characteristics: 2020-2022, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-national-detail.html; Kirsten J. Colello, “Who Pays for Long-Term Services and Supports?” Congressional Research Service, updated June 15, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10343.

[6] CBPP tabulations of 2021 American Community Survey data.

[7] Anita Soni, “Healthcare Expenditures for Treatment of Mental Disorders: Estimates for Adults Ages 18 and Older, U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population, 2019,” Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, February 2022, https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st539/stat539.pdf.

[8] Christian E. Weller, “African Americans Face Systematic Obstacles to Getting Good,” Center for American Progress, December 5, 2019, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/african-americans-face-systematic-obstacles-getting-good-jobs/; Anthony P. Carnevale et al., “The Unequal Race For Good Jobs: How Whites Made Outsized Gains in Education and Good Jobs Compared to Blacks and Latinos,” Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2019, https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/raceandgoodjobs/.

[9] Madeline Guth, Rachel Garfield, and Robin Rudowitz, “The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Studies from January 2014 to January 2020,” KFF, March 17, 2020, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review/; Madeline Guth and Meghana Ammula, “Building on the Evidence Base: Studies on the Effects of Medicaid Expansion, February 2020 to March 2021,” KFF, May 6, 2021, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/building-on-the-evidence-base-studies-on-the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-february-2020-to-march-2021/.

[10] Elizabeth Williams, Robin Rudowitz, and Alice Burns, “Medicaid Financing: The Basics,” KFF, April 13, 2023, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-financing-the-basics/.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Laura Guerra-Cardus and Gideon Lukens, “Last 11 States Should Expand Medicaid to Maximize Coverage and Protect Against Funding Drop as Continuous Coverage Ends,” CBPP, January 24, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/last-11-states-should-expand-medicaid-to-maximize-coverage-and-protect-against.

[13] CBPP, “The Medicaid Coverage Gap: State Fact Sheets,” updated March 3, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/the-medicaid-coverage-gap.

[14] KFF, “Medicaid Enrollment and Unwinding Tracker,” June 29, 2023, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-enrollment-and-unwinding-tracker/; Ashley Kirzinger et al., “The Unwinding of Medicaid Continuous Enrollment: Knowledge and Experience of Enrollees,” KFF, May 24, 2023, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/poll-finding/the-unwinding-of-medicaid-continuous-enrollment-knowledge-and-experiences-of-enrollees/.

[15] Allison Orris and Sarah Lueck, “Congressional Republicans’ Budget Plans Are Likely to Cut Health Coverage,” CBPP, updated March 20, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/congressional-republicans-budget-plans-are-likely-to-cut-health-coverage.

[16] Laura Harker, “Taking Medicaid Away for Not Meeting a Work-Reporting Requirement Would Keep People From Health Care,” CBPP, updated April 28, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/taking-medicaid-away-for-not-meeting-a-work-reporting-requirement-would-keep-people; Gideon Lukens, “McCarthy Medicaid Proposal Puts Millions of People in Expansion States at Risk of Losing Health Coverage,” CBPP, April 21, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/mccarthy-medicaid-proposal-puts-millions-of-people-in-expansion-states-at-risk-of.

[17] KFF, State Adoption of 12-Month Continuous Eligibility for Children’s Medicaid and CHIP, as of January 1, 2023, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-adoption-of-12-month-continuous-eligibility-for-childrens-medicaid-and-chip/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

[18] Elizabeth Williams et al., “Implications of Continuous Eligibility Policies for Children’s Medicaid Enrollment Churn,” KFF, December 21, 2022, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/implications-of-continuous-eligibility-policies-for-childrens-medicaid-enrollment-churn/.

[19] KFF, “Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Approved and Pending Section 1115 Waivers by State, Table 1, Section 1115 Eligibility Changes – Other Eligibility and Enrollment Expansions,” July 17, 2023, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-waiver-tracker-approved-and-pending-section-1115-waivers-by-state/#Table1.

[20] Ibid; CMS, “Opportunities to Test Transition-Related Strategies to Support Community Reentry and Improve Care Transitions for Individuals Who Are Incarcerated,” SMD #23-003, April 17, 2023, https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd23003.pdf.

[21] Reentry Act of 2023, H.R. 2400/S. 1165, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/2400/text?s=1&r=1&q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22Medicaid+Reentry+Act%22%5D%7D.

[22] Jennifer Sullivan et al., “New House Build Back Better Legislation Would Make Long-Lasting Medicaid Improvements,” CBPP, November 3, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/new-house-build-back-better-legislation-would-make-long-lasting-medicaid.

[23] KFF, “Health Coverage and Care of Immigrants,” updated March 30, 2023, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-and-care-of-immigrants/.

[24] LIFT the BAR Act, H.R. 4170, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/4170?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22lift+the+bar%22%5D%7D&s=1&r=1.

[25] States may offer Medicaid benefits on an FFS basis, through managed care plans, or both. Under the FFS model, the state pays providers directly for each covered service received by a Medicaid beneficiary. Under managed care, the state pays a fee to a managed care plan for each person enrolled in the plan. CMS’ two proposed rules are: CMS, Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Managed Care Access, Finance, and Quality Proposed Rule, 88 Fed. Reg. 28092, May 3, 2023, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2023-05-03/pdf/2023-08961.pdf; and CMS, Ensuring Access to Medicaid Services, 88 Fed. Reg. 27960, May 3, 2023, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/05/03#centers-for-medicare-medicaid-services.

[26] Allison Orris, “Newly Proposed Rule Would Help Kids, Seniors, and Others Get and Stay Enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP,” CBPP, September 12, 2022,https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/newly-proposed-rule-would-help-kids-seniors-and-others-get-and-stay-enrolled-in.

[27] Madeline Guth et al., “Medicaid and Racial Health Equity,” KFF, June 2, 2023, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-and-racial-health-equity/.