CBO Provides New Evidence That the 2001 and 2003 Tax Cuts Have Only Modest Economic Effects And Do Not Pay For Themselves

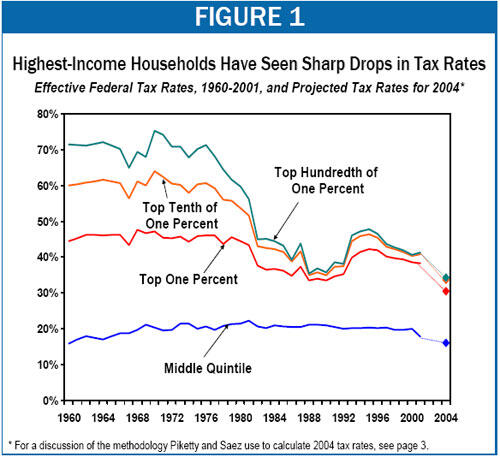

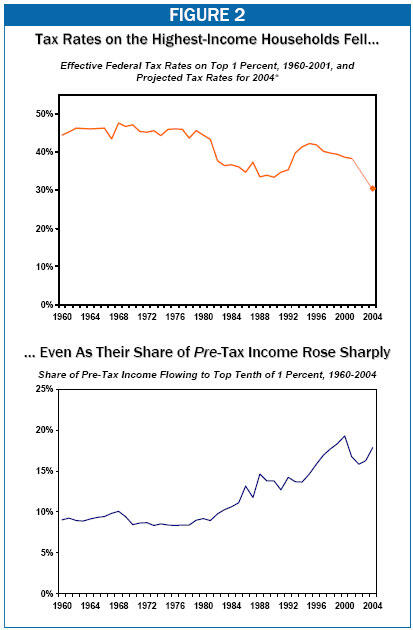

Largest Reductions in Progressivity Occurred in 1980s and Since 2000

End Notes

[1] Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, “How Progressive Is the U.S. Federal Tax System? A Historical and International Perspective,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Winter 2007. Thomas Piketty is a professor of economics at the Paris School of Economics. Emmanuel Saez is a professor of economics at the University of California Berkeley. This analysis also relies on data the authors made available on the web: http://elsa.berkeley.edu/~saez/jep-results-standalone.xls.

[2] A household’s effective tax rate is the share of its income actually paid in taxes, taking into account deductions, exclusions, and other provisions that raise or lower tax liability. The Congressional Budget Office publishes data on effective federal tax rates going back to 1979 that include income, payroll, corporate, and excise taxes, but not estate taxes. CBO examines income groups up to the top 1 percent, but not groups within the top 1 percent. For those years and income groups for which CBO and Piketty and Saez both provide data, the trends in the data are very similar.

[3] Congressional Budget Office data show the same trend.

[4] For a discussion of the methodology Piketty and Saez use to calculate 2004 tax rates, see page 3.

[5] High-income households likely faced somewhat higher effective federal tax rates in 2005 because corporate tax revenues increased significantly in 2005. Economists generally assume that the burden of corporate taxes falls on households in proportion to their shares of total investment income; high-income households hold the lion’s share of investment income. As a result, increases in corporate tax payments generally raise effective tax rates for these households.

[6] Some supporters of recent tax cuts have claimed that these tax cuts are progressive because, since they were enacted, the share of taxes paid by high-income groups has increased. As Piketty and Saez point out, “when the share of income received by the top income groups is changing, the share of tax paid by those top income groups is a misleading method for evaluating the progressivity of the tax system.” This measure is also misleading when used to evaluate the progressivity of deficit-financed tax cuts. For further discussion, see Aviva Aron-Dine, “Have the 2001 and 2003 Tax Cuts Made the Tax Code More Progressive,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 19, 2007, https://www.cbpp.org/3-19-07tax.htm.

[7] Specifically, they use the available data on aggregate income growth between 2000 and 2004, but assume the 2000 income distribution. That is, they simulate what tax rates would have been in 2004 had all households’ incomes grown at the same rates between 2000 and 2004. (This approach is similar to that used by the Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center and many other analysts.) In fact, the incomes of the highest income households grew less between 2000 and 2004 than those of other households (due to large income losses in 2001 and 2002, following the decline in the stock market). In actuality, therefore, the incomes of the highest-income households were lower in 2004 than Piketty and Saez assume for purposes of their simulation, and these lower incomes likely translated into lower tax rates. Thus, the actual decline in tax rates at the pinnacle of the income scale was likely slightly larger than Piketty and Saez project. Piketty and Saez’s methodology captures only the decline in effective rates due to legislative changes, not the decline in effective rates due to changes in the income distribution.