- Home

- Bowles-Simpson Plan Commendably Puts Eve...

Bowles-Simpson Plan Commendably Puts Everything on the Table But Has Major Deficiencies Because It Lacks an Appropriate Balance Between Program Cuts and Revenue Increases

Plan Needs Substantial Improvement in Key Areas

I. Overview and Summary

The November 10 plan from the co-chairs of President Obama’s Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform helps move the budget debate beyond misguided claims that policymakers can tame deficits simply or primarily by eliminating earmarks and “waste, fraud, and abuse.” It also wisely subjects all parts of the budget to review and outlines an array of hard choices.

Unfortunately, the plan does not represent a truly balanced approach to bringing deficits under control. The co-chairs — former Clinton White House Chief of Staff Erskine Bowles and former Republican Senator Alan Simpson — describe a real problem of deficits and debt that will grow to unsustainable levels, and they propose a number of policy changes that should be part of any serious debate on the budget. Yet, as a whole, their package falls far short of an appropriate or equitable plan for the federal budget in the years and decades ahead, as a careful analysis of it shows.

Specifically, the plan starts to take effect in fiscal year 2012, which could threaten the fragile economic recovery; it proposes policy steps that would prove a serious hardship for some of the nation’s most disadvantaged individuals; it relies far too much on spending cuts as opposed to revenue increases (both as a whole and, in particular, in its proposals to strengthen Social Security’s finances); and it calls for adopting policies that will hold annual revenues and spending to 21 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in future decades, which is both unrealistic and unwise.

Bowles and Simpson presented their plan as a “starting point” for the commission’s deliberations. This analysis focuses on the areas where their plan poses the most serious problems; it identifies the aspects of it that the commission most needs to change if the “starting point” is to become a balanced plan that would help to put the federal budget on a sound course without causing substantial damage in the process.

The Plan’s Principles

The plan starts with a series of “guiding principles,” most of which are exemplary. But, as this analysis explains, the specifics of the plan violate some of the co-chairs’ core principles — namely, the principle “Don’t Disrupt a Fragile Economic Recovery” and the principle to “Protect the Truly Disadvantaged.” In addition, at least one principle is deeply misguided and could do serious harm to the nation in the future — the call to hold revenues and spending to no more than 21 percent of GDP, despite the challenges the nation faces in the decades ahead. [1]

“Don’t Disrupt a Fragile Economy”

The proposal to start implementing budget cuts in fiscal year 2012 — a short 10½ months from now — runs a substantial risk of impeding the economic recovery. In its most recent economic forecast, the Congressional Budget Office projects that unemployment will still average 8.4 percent in fiscal year 2012 and that the gap between actual GDP and its potential level will not be closed until the end of 2014. A growing number of private economic forecasters are expressing deepening concern over the economy’s lack of steam and its potential to experience growth too anemic to lower unemployment significantly over the next few years. It would be far better to delay implementation of significant deficit-reduction policies at least until fiscal year 2013, when there should be less chance of stifling the recovery and locking the economy into a long period of sub-par performance.

“Protect the Truly Disadvantaged”

While the plan aims to avoid violating the co-chairs’ principle “to protect the truly disadvantaged” by not proposing widespread cuts in means-tested programs, it nevertheless threatens benefits and services for millions of Americans who have very modest incomes and would experience significant hardship.

For instance, while the proposed changes in Social Security would produce benefit increases for many among the poorest fifth of Social Security beneficiaries — a praiseworthy accomplishment — the changes would cut benefits for those in the next-to-the-bottom fifth and the middle fifth of beneficiaries. Social Security Administration data show that in 2008, the median income for elderly Social Security beneficiaries (including any income they get from other sources, as well as their spouses’ income) was only $14,100 for those in the next-to-the-bottom fifth and $20,600 for those in the middle fifth.

Indeed, the plan would cut Social Security benefits for a medium earner (one whose earnings are in the middle of the wage distribution) by 15 percent below the currently scheduled amount in 2050 and 22 percent by 2080. Yet a lifelong medium earner who retires at age 65 in 2010 receives a benefit of just $1,397 a month, or $16,764 a year — which is only about 55 percent above the poverty line — and generally does not have significant income from other sources.

The plan’s cuts in Medicaid and Medicare would pose further problems for millions of people of modest means. The plan calls for increasing the amounts that elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries must pay for health care services (presumably through higher co-payments) under both Medicare and the Medigap policies that supplement Medicare coverage. The plan lacks details on how these changes would work, and they might well be reasonable parts of a balanced deficit-reduction plan — if they were not being extracted from the same modest-income seniors and people with disabilities whose Social Security benefits were being cut at the same time. As Drew Altman, the highly respected president of the Kaiser Family Foundation, recently explained, many of these modest-income Social Security and Medicare beneficiaries

have low incomes and already pay a significant share of their incomes for health care today. It will be difficult if not impossible to ask the majority of beneficiaries to pay more or make do with less. This has been the missing element in the entitlement/deficit reduction debate: Warren Buffet is not the typical Medicare beneficiary. Instead the prototype is an older woman with multiple chronic illnesses living on an income of less than $25,000 who spends more than 15 percent of her income on health care. It is the people on these programs and the realities of their lives that have been left out of the discussion.[2]

Another health-care element of the plan poses still greater risks for the nation’s most vulnerable people by threatening severe cuts over time in Medicaid, Medicare, and the subsidies to help modest-income people purchase coverage in the new insurance exchanges that the health reform law will establish. The plan proposes to contain growth after 2020 in federal health expenditures for these programs and the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored insurance to no more than 1 percent more per year than the rate of growth in GDP.

Tough, but rational, targets for slowing health care cost growth virtually always are based on per- beneficiary costs, not aggregate costs. For example, the target for Medicare cost growth that the Independent Payment Advisory Board established by the health reform law must hit is GDP plus 1 percent per beneficiary.[3] The difference here is crucial. The Bowles-Simpson target is for total health program costs, rather than costs per beneficiary, to rise no faster than GDP+1; that would likely lead to draconian results. It would mean that as the share of the population that is elderly increases, cuts of increasing severity likely would have to be made in Medicaid and Medicare to fit total federal health-care expenditures within an entirely unrealistic constraint. Over time, the effects on vulnerable Americans could be grim.

Why the Plan Has These Serious Deficiencies

The extent and depth of these and other budget cuts that would overreach and threaten the ability of the federal government to meet the nation’s needs are largely the result of a problem that lies at the heart of the co-chairs’ plan — its highly unbalanced nature. If the co-chairs had not adopted the misguided principle of holding federal outlays in future decades to no more than 21 percent of GDP and had produced a plan that was more balanced — one that did not propose to extract two-thirds of its deficit reduction from program cuts and only one-third from increased revenues and that instead struck an even balance — they could have avoided some or all of the elements of the plan that risk doing the greatest harm and could have done so without raising taxes too much. If half of their proposed deficit reduction were achieved by revenue increases, revenues in 2020 would be about 20.7 percent of GDP, about where they were in 2000. (It is noteworthy that even with the revenue measures in the plan, it would leave revenues below where they would be under current law — that is, where they would be if the Bush tax cuts and other expiring provisions of tax law were allowed to expire or had the costs of extending them paid for through offsetting revenue-raising measures. Compared to a “current law” baseline, the co-chairs’ plan actually lowers revenues and gets all of its deficit reduction from budget cuts.)

The same lack of balance is reflected in one of the most controversial aspects of the Bowles-Simpson plan — its Social Security recommendations. Analysis of its recommendations by the Social Security actuaries shows that over the next 75 years, two-thirds of the solvency improvements in the co-chairs’ plan would come from Social Security benefit cuts and only one-third from new revenues — and that by the 75th year, fully 80 percent (or four-fifths) of the financing improvements would come from benefit cuts, with just one-fifth coming from revenues. No past bipartisan Social Security plan has ever tilted so heavily toward cutting benefits; a 50-50 split has been a more traditional goal for bipartisan efforts. Here, as well, the lack of a balanced approach is responsible for the most severe problems that the co-chairs’ recommendations would cause.

Bowles and Simpson have been praised as “brave” in proposing their plan. This certainly is true in many respects. But their plan is not brave regarding the level of revenues the nation will need in the future, and does a disservice by not leveling with the American public on this issue. The plan also does not say a word about the most consequential deficit issue that Congress faces immediately — the fate of the Bush tax cuts for high-income households, which if made permanent, would widen deficits and debt by as much as the entire Social Security shortfall that the plan proposes to close in a painful manner.[4] It will be especially difficult to explain a proposal to cut Social Security benefits and raise Medicare co-payments on elderly widows living on $20,000 a year if Congress has just made permanent tax cuts that average over $100,000 a year for people making over $1 million a year.

Finally, the plan pretends that federal expenditures and revenues can be held to 21 percent of GDP for decades to come, despite the aging of the population and continued increases in health care costs, which are inevitable (hopefully at a reduced growth rate) as a result of continued advances in medical technology that improve health and lengthen lives, but at added cost.

The notion that limiting federal expenditures to 21 percent of GDP in coming decades represents an extreme position — and will require draconian cutbacks and produce undesirable results — is broadly shared among budget analysts (except those on the Right end of the political spectrum). At a recent Brookings Institution event on deficit reduction, panelists in or near the center of the political spectrum concurred that to meet the nation’s needs 20 years or so from now, revenues will need to be in the 23 percent to 25 percent of GDP range. Moreover, when an expert committee on deficit reduction convened by the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Public Administration issued a major report earlier this year, it outlined four possible paths to stabilize the debt.[5] Committee co-chair (and former CBO director) Rudolph Penner explained that the committee designed paths at two “extremes” — one that achieved most of its deficit reduction by cutting programs and another that got most of its deficit reduction by raising taxes — and two intermediate paths that blended program and tax changes. The extreme low-spending path included cuts that ultimately became deep in Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, and reductions of about 20 percent in aggregate funding for all other federal programs including defense, education, infrastructure, veterans’ health care, veterans’ disability payments, medical research, and the like. Under this extreme path, federal spending would be about 21 percent of GDP — the very level that Bowles and Simpson propose as a target. As the NAS report indicates, this level is not achievable over time without devastating cuts that violate Bowles and Simpson’s own principles (including the principle to “invest in education, infrastructure, and high-value R&D”). [6]

II. The Plan’s Pluses

The co-chairs deserve credit for forthrightly rejecting claims that many people have used to avoid engaging in a serious debate about the budget. They make clear that the budget can only be put onto a sustainable path through a combination of reductions in spending and increases in revenues. While this conclusion is commonplace among serious budget analysts, it runs counter to the claims heard from too many policymakers that the budget problem is simply a spending problem and that revenue levels under current policies will be adequate to fund the government in coming decades. (This conclusion also runs counter to the claim that we do not need to reduce spending below the levels under current policies, but that claim is one that few lawmakers now are making.)

Bowles and Simpson also face the fact that it is not possible to reduce federal spending substantially without cutting programs that are popular and provide benefits to millions of Americans — and without cutting the defense budget. This, too, is obvious to anyone who has carefully examined the federal budget but runs counter to claims made by lawmakers such as Senator Jim DeMint, who recently said on “Meet the Press” that “If we can just cut the administrative waste we can cut hundreds of billions of dollars a year at the federal level.”

Nor do the co-chairs let lawmakers off the hook by blaming the inability of policymakers to agree on a deficit reduction plan on problems with the budget process. They do propose some process changes to help enforce policy decisions, such as multi-year caps on discretionary spending at levels agreed to by lawmakers as part of an overall budget deal. But they do not evade the need to face up to real policy decisions on specific programs and taxes by focusing instead on budget process changes that are supposed to make lawmakers enact budget cuts or tax increases in the future that they are unwilling to make today — an approach that has failed before.

Beyond injecting some reality into the budget debate, the co-chairs have included in their plan a number of proposals that deserve serious consideration in any discussion of deficit reduction. Many — such as reducing subsidies to large and prosperous farms, ending first-dollar coverage of Medicare co-payments by Medigap insurance, eliminating tax breaks for certain companies or industries, curtailing certain individual income tax breaks, raising the gasoline tax (to fund needed infrastructure projects), and using a more accurate measure of inflation for cost-of-living adjustments in benefit programs and annual inflation adjustments in the tax code — represent sound ways to produce deficit reduction or meet important needs without adding to the deficit.

III. The Plan’s Minuses

Despite the plan’s laudable features, its adoption would be unwise without substantial changes. Because the proposed savings are so heavily skewed to the spending side of the budget — roughly two-thirds of the deficit reduction comes from spending cuts, with only one-third coming from increased revenues[7] — the plan calls for much deeper cuts in some program areas than would be wise (and likely would be sustainable) over time.

For instance, the proposed savings in Medicaid could undercut health reform, both by making it more difficult to ensure that reimbursement rates will be adequate to attract enough providers to serve the greatly increased number of low-income people who will be served through Medicaid and by cutting the federal share of state Medicaid administrative costs just as states will face large increases in those costs to handle the larger Medicaid beneficiary population. Similarly, the plan proposes to accelerate cuts in payments to hospitals that provide charity care to the uninsured without accelerating the health reform coverage expansions that make those budget cuts viable in the first place. And it proposes a new round of cuts in payments to Medicare providers on top of the substantial cuts that the health reform law already makes, which in turn could lead many physicians and other providers to decline to accept Medicare patients.

Stan Collender on the Plan’s Federal Workforce Proposals

Stan Collender of Qorvis Communications, one of Washington’s leading budget experts for more than 30 years, issued a short commentary last week on the Bowles-Simpson plan. In discussing the plan’s federal workforce proposals, Collender observed:

The plan calls for a substantial reduction in federal employees. A reduction in employees generally results in the government relying on more outside consultants to get the work done but, in addition to the recommended reductions-in-force, Bowles and Simpson also calls for significant cuts in the use of contractors.

The combination of those two seems to indicate that the now smaller number of federal employees will have to do everything that was done before, that is, that they will have to be much more productive. But Bowles and Simpson also calls for a three-year freeze on federal employee salaries, and that almost inevitably means an increasing number of federal workers will quit. That will reduce rather than increase productivity as new and less experienced workers replace the more senior folks who will have left for greener pastures.

In other words, Bowles and Simpson projects substantial savings based on the expectation that a less experienced and much smaller federal workforce will be more productive and just as effective as the more experienced and larger workforce it replaces. That makes absolutely no sense.

Stan Collender, “The Bowles-Simpson Deficit Reduction Plan Doesn’t Add Up,” November 11, 2010,

Another example involves the proposals affecting the federal workforce. Nearly half of the $100 billion in possible domestic discretionary cuts in 2015 that the plan lists would come from freezing federal salaries and compensation for three years, substantially cutting the number of staff at every federal agency except those dealing with national security, and slashing the number of government contractors — all at the same time. Taken together (and especially in light of the co-chairs’ proposal to achieve mandatory savings by significantly reducing the value of retirement benefits for federal employees), this package of cuts seriously overreaches. It would make it hard for the federal government to keep and attract qualified workers and would reduce the ability of the remaining workers to manage the operations of the federal government effectively. It is difficult to justify, for example, cutting staffing at the Social Security Administration just as the baby boom generation retires in large numbers and the number of Social Security beneficiaries swells. As long-time budget expert Stan Collender has explained, taken as a whole, this package of charges would make the federal government less productive, less efficient, and less competent in performing its work. (See the box above).

Deleterious cuts such as these could be avoided or reduced under a more balanced plan that counts on increased revenues for at least half of the targeted deficit reduction.

The highly disproportionate reliance on budget cuts in the co-chairs’ plan stems from the misguided determination to constrain spending to 21 percent of GDP, approximately the average for federal government spending over the last 40 years. As a major analysis that the Center issued in July explains, a 21 percent of GDP target ignores the reality that circumstances today are very different than they were over the past 40 years; it would be impossible to limit federal spending to the average of past decades without making cuts of extraordinary severity in Social Security, Medicare, and an array of other crucial federal activities.[8]

The aging of the population and continuing increases in the per-person cost of health care (in both the private and public sectors) will increase the cost of meeting longstanding federal commitments to seniors and people with disabilities. Furthermore, federal responsibilities have grown in recent years in a number of areas — aid to veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, homeland security in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks (the federal government spent little in this area before 2001), education (the federal government promised to help states meet the new requirements imposed by the No Child Left Behind Act), the Medicare prescription drug benefit, and health reform that extends coverage to millions who would otherwise be uninsured (health reform legislation reduced the deficit, but increased federal spending). Moreover, spending for interest on the debt will be substantially higher in the future as a result of the large growth in the debt held by the public relative to the size of the economy.

Because of the increased cost of both longstanding and recent federal commitments, it does not make sense to assume that federal spending in coming decades should be no greater than it was on average over the last four decades. And another factor makes this problem still worse. The Bowles-Simpson plan would curb the tax break for employer-sponsored health coverage, thereby encouraging more employers to drop coverage and shift their employees to the health exchanges created under health reform, where many would receive federal subsidies to purchase coverage. That change would increase both taxes and spending as a share of GDP, and it is another illustration of why capping revenues at — and aiming to limit spending to — 21 percent of GDP for decades to come would be misguided.

Social Security Proposal Would Impose Hefty Benefit Cuts on Seniors And People with Disabilities Who Are Not Affluent

The co-chairs’ proposal would assure Social Security’s long-run solvency but at the cost of making significant benefit cuts for most retirees, including many with modest incomes.

Past discussions of potential bipartisan plans to restore Social Security solvency have often envisioned half of the solvency improvements coming from increased revenues and half from benefit reductions. And in recent years, a number of Social Security experts have pointed out that even that goal may be hard to achieve in a reasonable manner. Social Security benefits already are very modest, are being reduced further as a result of benefit cuts enacted in 1983 that are still being phased in, and are steadily being eroded further by rising Medicare premiums, which climb at a faster rate than Social Security benefits and are deducted from Social Security checks. Nevertheless, the co-chairs’ proposal relies on Social Security benefit cuts for two-thirds of its improvements in solvency over the next 75 years. By the 75th year, the plan gets four-fifths of its financing improvement from benefit cuts and just one-fifth from revenues. (A statement that 43 percent of the Social Security savings would come from tax increases is mistaken; see the box on page 9.)

The proposal would cut Social Security benefits in three ways:

- Increasing the Retirement Age . Currently, retirees may claim Social Security benefits starting at age 62. The full retirement age used to be 65, is now 66, and is scheduled to increase to 67 for people born in 1960 and later. The co-chairs’ plan would index the full retirement age to life expectancy (after it reaches 67) and would increase the “early eligibility age,” or the age at which people can claim a reduced level of benefits. By about 2050, the early eligibility age would reach 63 and the full retirement age would reach 68. By about 2075, the early eligibility age would reach 64 and the full retirement age would reach 69.

The Mix of Benefit Cuts and Tax Increases in the Bowles-Simpson Social Security Proposal

Calculating the fraction of savings attributable to benefit cuts and the fraction attributable to tax increases in the co-chairs’ Social Security proposal has given rise to some confusion. The confusion stems in part from the fact that the proposal includes not only changes in benefits and taxes but also an expansion of Social Security coverage to newly hired employees of state and local governments.

At present, about 30 percent of state and local employees are not covered by Social Security, although many of them eventually qualify for Social Security based on other work. The proposed expansion of coverage to more state and local employees creates an initial infusion of revenues, but it has essentially no effect on Social Security solvency after 75 years because the additional payroll taxes paid by state and local workers result in a roughly equal increase in benefits paid. Because this proposal affects revenues and benefits equally in the long run, it should not be included in calculating the balance between benefit cuts and tax increases.

The analysis the Social Security actuaries produced for the co-chairs shows that, excluding the proposal to expand coverage, the plan eliminates Social Security’s 75-year deficit by improving Social Security’s finances by an amount equal to 2.03 percent of taxable payroll over 75 years.a (Taxable payroll represents the amount of earnings in the U.S. economy that are subject to the Social Security payroll tax.) The proposed increase in the amount of earnings subject to the payroll tax — the one tax increase in the plan — accounts for 0.67 percentage points, or one-third of the total; the benefit reductions account for the remaining two-thirds.

After 75 years, the plan improves Social Security’s finances by 4.43 percent of payroll, of which the increase in the amount of earnings subject to the payroll tax represents 0.90 percentage points — just one-fifth of the total. Net cuts in benefits provide the other four-fifths of the savings.

Some proponents of the plan have asserted that benefit cuts provide 57 percent (rather than 67 percent) of the savings over the first 75 years. This claim not only counts the extension of coverage to more state and local workers as a tax increase but also mistakenly uses the wrong denominator. (It uses the amount of Social Security’s 75-year deficit rather than the total amount of the changes that the co-chairs actually propose, which is a somewhat larger number.)

a Stephen C. Goss, Chief Actuary, Social Security Administration, Memorandum to Fiscal Commission Staff, November 9, 2010, http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/solvency/FiscalCommission_20101109.pdf.

Although this is not widely understood, an increase in the full retirement age amounts to an across-the-board cut in benefits for people at all earnings levels, regardless of the age at which they retire. A one-year increase in the full retirement age is equivalent to roughly a 7 percent cut in benefits for a person retiring at any given age, whether it is age 65, age 67, or age 70. The proposal also specifies that the Social Security Administration should develop a way to allow continued retirement at age 62 for people in physically demanding jobs. This is a laudable goal, but experts have wrestled with it for years and have been unable to come up with an effective way of doing so. - Changing the Benefit Formula. The proposal would further reduce benefits by changing the program’s basic benefit formula. The cuts would be greatest for workers with above-median earnings but would affect the majority of retired and disabled workers. (The document the co-chairs distributed gives the impression that this change would affect only the top half of beneficiaries, but the Social Security actuaries’ analysis of the proposal, made public last week, shows that some beneficiaries in the bottom half would be affected as well.)Image

- Reducing Cost-of-Living Adjustments. The proposal would reduce cost-of-living adjustments by about 0.3 percentage points a year by adopting a different measure of inflation, the chained Consumer Price Index, which analysts generally regard as a more accurate measure of inflation for the economy as a whole. This change would start in December 2011 and affect everyone on the benefit rolls at that time. Its effect would be softened by providing a 5-percent benefit increase to people after they have been eligible for benefits for 20 years. This change in the CPI measure also would be applied to cost-of-living adjustments in other benefit programs and the annual inflation adjustments in the tax code, a change that a number of analysts (including the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities) have recommended for some time.

The co-chairs’ plan also contains the following elements:

- Providing a New Minimum Benefit for Lifetime Low-Wage Earners Equal to 125 Percent of the Federal Poverty Level. The full minimum benefit would be available to workers who have earned at least $4,480 a year (in today’s terms) for 30 years. This would increase benefits for very low-wage workers.

- Covering All Newly Hired State and Local Workers under Social Security . At present, about 30 percent of state and local government workers remain outside the Social Security system, although many of them eventually qualify for Social Security based on other work.

- Increasing the Amount of Earnings Subject to the Social Security Payroll Tax. The proposal would gradually increase the maximum taxable amount so that 90 percent of all earnings would be subject to the tax by 2050. This is the one revenue provision in the plan.

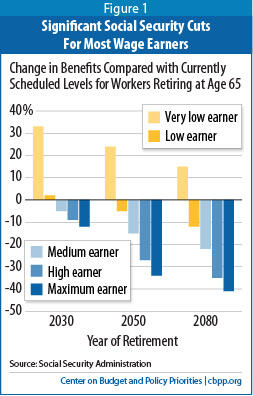

As a result of these changes, all beneficiaries except those with low earnings throughout their career would face significant losses in benefits (see Figure 1). The benefit of a medium earner (someone earning about $43,000 in today’s terms) would be cut by 15 percent below the currently scheduled amount in 2050 and by 22 percent in 2080.[9]

The typical beneficiary could not easily absorb such reductions. As noted earlier, Social Security benefits are modest; a lifelong medium earner retiring at 65 in 2010 receives a benefit of just $1,397 a month ($16,764 a year), only about 55 percent above the poverty line and barely more than what researchers reckon is a “no-frills, bare-bones” budget for retirees. The typical retiree does not have significant income from other sources.

The overly deep benefit reductions in the plan are a result of the previously noted lack of balance between Social Security benefit cuts and revenue increases, with two-thirds of the Social Security savings coming from benefit cuts over the next 75 years, and four-fifths coming from benefit cuts by the 75th year.

Health Care Savings Likely to Be Overly Ambitious

The co-chairs’ plan identifies $282 billion in health care savings over the next ten years to pay for the cost of fixing Medicare’s flawed payment formula for physicians (the sustainable growth rate formula, or SGR). It also calls for an additional $200 billion in health care savings through 2020 and provides illustrative options that total $395 billion. After 2020, the proposal would set a target for limiting the growth of total federal health spending to the rate of GDP growth plus one percentage point. This global target would apply to Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, the premium subsidies and cost-sharing assistance that many participants in the health insurance exchanges would receive, and the value of the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance.

Some of the co-chairs’ specific health-care proposals are troublesome because they could harm low- and moderate-income individuals and families. Examples include the proposals to increase cost-sharing for Medicaid beneficiaries (most of whom live in poverty), place elderly and disabled Medicaid beneficiaries in managed care (which could pose risks for very frail seniors and people with severe disabilities and ought to be tested and evaluated with this group before being applied to millions of poor elderly and disabled people nationwide), convert federal Medicaid payments for long-term care into a block grant, cut the federal share of state Medicaid administrative costs even as states face much larger Medicaid caseloads as a result of health reform, and accelerate cuts in payments to hospitals that provide charity care to the uninsured.

Of still greater concern is whether the plan’s overall level of health care savings can be achieved without creating widespread health-care access problems or impairing the quality of care. If not, beneficiaries with low incomes would likely suffer the most because they would be unable to afford to purchase supplemental care, such as Medigap policies that supplement Medicare coverage.

Another problem stems from the design of the plan’s longer-term target for constraining health-care program costs. The provisions of the health reform law (the Affordable Care Act, or ACA) in this area are already tough. The ACA establishes an Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB) that is charged with developing and submitting proposals to slow the growth of Medicare spending if the projected growth in Medicare spending per beneficiary exceeds a specified level. In 2018 and subsequent years, the ACA directs the IPAB to limit the growth of Medicare spending per beneficiary to per-capita GDP growth plus one percentage point.[10] The ACA also limits growth in federal costs for the refundable tax credits that will be provided to help low- and moderate-income people purchase health insurance coverage in the new state-based health insurance exchanges. After 2018, the tax credit for someone at a given income level will be constrained to grow no faster than consumer prices rather than keep pace with health costs, which means that the subsidies will cover a smaller share of premium costs — and beneficiaries will pay a larger share — with each passing year.[11]

The Six Most Important Improvements Needed in the Plan

In unveiling their plan, Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson stressed that it was only a starting point. Based on the analysis in this paper, we regard the following as the six most important changes needed in the plan.

- Relax the revenue and expenditure targets. The proposal to cap revenues at an arbitrary level of 21 percent of GDP is highly ill-advised in light of the aging of the population, continued increases in health care costs, and the fact that the United States could face major unforeseen challenges in the future — at home or abroad — that require expenditures that cannot be anticipated today. Similarly, limiting expenditures to 21 percent of GDP in future decades will be impossible without draconian and unsound cutbacks in essential areas.

- Address the imbalance between budget cuts and revenue increases. The highly problematic features in the plan stem largely from an effort to extract two-thirds of the deficit reduction from budget cuts and only one-third from revenues.

- Address the overly deep benefit cuts on Social Security beneficiaries of modest means. Here, too, the problems stem from excessive reliance on benefit cuts and inadequate contributions from revenues. It is not possible to take two-thirds of the Social Security savings from benefit cuts —rising to four-fifths by the 75th year — without doing serious damage to people who can’t afford to absorb those cuts.

- Scale back excessive health care cuts, especially those that could harm vulnerable people or endanger health reform. Policymakers should also ensure that any health care expenditure target for future decades is set on a per-beneficiary basis, with adjustment for demographic changes in the mix of beneficiaries.

- Moderate the depth of the domestic discretionary cuts, particularly with an eye to ensuring that the federal government can function effectively. Cuts that would impair federal agencies’ ability to perform their assigned tasks should be avoided.

- Avoid instituting cuts 10½ months from now (i.e., in fiscal year 2012) in order to avoid impeding the fragile economic recovery. The cuts should not begin before fiscal year 2013 to give the economy more time to get a point where it can safely absorb them.

Some analysts have questioned whether these ACA targets can be achieved without impairing the access of Medicare beneficiaries to doctors and hospitals and without making health insurance unaffordable over time to many people with modest incomes. In light of these concerns, it would not be prudent to count on additional very large budgetary savings from imposing even tighter limits, as the Bowles-Simpson plan would do — unless the growth in private health spending can also be slowed further. Further limiting the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance, as the co-chairs propose, would help to slow the growth of private health spending somewhat, but their proposal is much more heavily weighted toward reductions in federal health programs.

Growth in health care costs is not driven by factors that are unique to Medicare, Medicaid, and other federal health programs. To the contrary, for 30 years, per-beneficiary spending in Medicare and Medicaid has grown at rates nearly identical to those for the overall health care system. Attempting to force substantial cuts in federal health spending without requiring comparable measures to restrain the growth of health costs system-wide would likely disadvantage the poor, the elderly, and people with serious disabilities.

The plan’s call to limit the growth of total federal health program expenditures to the growth of GDP plus one percentage point is likely to prove an impossibly stringent standard. Unlike the Medicare spending target in the ACA — which is based on the growth in spending per beneficiary — the health spending target that the co-chairs have proposed makes no allowance for circumstances where the number of beneficiaries grows more rapidly than the overall population. Yet that is precisely what is expected to occur in Medicare and Medicaid, as members of the baby boom generation move into their retirement years.

The proposal also neglects to make any adjustment for changes in the composition of the beneficiary population. Health care costs much more for elderly Medicaid beneficiaries than for child beneficiaries and working-age adults; this is a crucial consideration, because in the years after 2020, the proportion of Medicaid beneficiaries who are elderly will rise while the proportion who are younger will decline, raising overall program costs even if the growth in costs for health services has been successfully contained. Moreover, the co-chairs’ tax reform proposals may themselves push up the cost of the tax credits in the health insurance exchanges; reducing or eliminating the tax preference for employer-sponsored insurance, as the plan proposes, will likely cause fewer employers to offer coverage and more workers therefore to qualify for subsidies in the exchanges.

Because it does not take these factors into account and departs from the normal approach of designing health-care cost-growth targets on a per beneficiary basis, this aspect of the plan likely could lead over time to cutbacks that have sharp effects on large numbers of very vulnerable people, especially those who have limited incomes and serious health conditions. To be sure, the plan’s health-care cost-growth target would not be a hard cap that triggers automatic cuts if it is exceeded. But even requiring the President and Congress to propose and consider cuts to shrink program costs to get down to the target, as the co-chairs propose, could result in policy changes that would be very harmful. Furthermore, lawmakers who support a hard cap on health spending might adopt the commission’s recommended target as a hard cap. It is therefore important that any target be set judiciously and appropriately.

IV. Conclusion

The co-chairs have struggled to develop a plan that they hope can lead to a bipartisan deficit-reduction effort. They have put all components of the budget on the table and laid down proposals for specific program and tax changes. But they have fallen well short on basic considerations of balance and equity and have produced a plan that — despite their intentions — would harm millions of people who are disadvantaged or have very modest incomes. In some areas, the plan also does not appear sufficiently well thought through. To address these significant shortcomings, the plan needs important modifications.

The co-chairs have described their plan as a starting point. The question now is whether the commission members and the co-chairs will make the changes that are badly needed.

End Notes

[1] One of the co-chairs’ guiding principles is to “Bring spending down to 22% and eventually to 21% of GDP.” Under their proposal, spending would be about 22% of GDP in 2020.

[2] Drew Altman, “The People Behind the Entitlement Debate,” Pulling It Together, Kaiser Family Foundation, November 11, 2010, http://www.kff.org/pullingittogether/People-Behind-The-Entitlement-Debate.cfm .

[3] Technically, the IPAB target is that Medicare costs per beneficiary should grow no faster than GDP per capita plus 1 percentage point.

[4] The plan’s tax reform proposal is intended to raise approximately the same share of revenues from high-income taxpayers as they would pay if the 2001 and 2003 high-income tax cuts are allowed to expire. But part of the plan’s purpose is to educate policymakers and the public and to talk straight with them, and decisions on the high-end tax cuts are imminent, while the changes the plan proposes in tax expenditures like the mortgage interest deduction, the deduction for charitable giving, the deduction for contributions to retirement plans, the employer health exclusion, and preferential tax rates for capital gains and dividends are among the least likely components of the plan to be enacted.

[5] National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences and National Academy of Public Administration, “Choosing the Nation’s Fiscal Future,” January 2010.

[6] The report stated that the low spending “path would limit what government can do to provide health care, pensions, and a range of other benefits. Certainly, in that scenario, many people who rely on the federal government for income, health care, or other benefits will suffer, even if some spending reductions are offset by more efficiency in government programs. Much slower spending growth would almost certainly also slow the rate of public investment in future growth — in people, infrastructure, and technology — which would probably limit the opportunities for future generations.” Ibid, pp. 69-70.

[7] According to the table on page 11 of the co-chairs’ plan, discretionary and mandatory savings combined account for $241 billion (71 percent) of the total policy changes of $339 billion in 2015 (this does not include reductions in debt service, which result from the changes in spending and tax policies). These savings account for $360 billion (64 percent) of the total policy changes of $564 billion in 2020, and $2,197 billion (70 percent) of the total policies changes of $3,158 billion in 2012 through 2020.

[8] Paul N. Van de Water, “Federal Spending Target of 21 Percent of GDP Not Appropriate Benchmark for Deficit-Reduction Efforts,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 28, 2010.

[9] Stephen C. Goss, Chief Actuary, Social Security Administration, Memorandum to Fiscal Commission Staff, November 9, 2010, http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/solvency/FiscalCommission_20101109.pdf.

[10] Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Public Law 111-148), as amended, section 3403.

[11] Affordable Care Act , section 1401.