- Home

- A State Of Decline: What A TABOR Would M...

A State of Decline: What a TABOR Would Mean for Kansas

If a constitutional amendment to limit expenditures — similar to Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR) — had been in place over the last decade in Kansas, state services would have deteriorated substantially. Had the TABOR limit most recently proposed by state Representative Brenda Landwehr (House Concurrent Resolution 5015) and the Americans for Prosperity Foundation taken effect in 1993, a cumulative total of $8.4 billion would have been cut from state expenditures for programs and services over the ensuing 12 years.

State General Revenue Fund expenditures in fiscal year 2005 could be no higher than $3.8 billion, had the Kansas TABOR limit begun in 1993.

- The limitation would have held FY 2005 expenditures to approximately $890 million below actual expenditures.

- The limit would have required expenditures for FY 2005 to be 19 percent lower than they actually were.

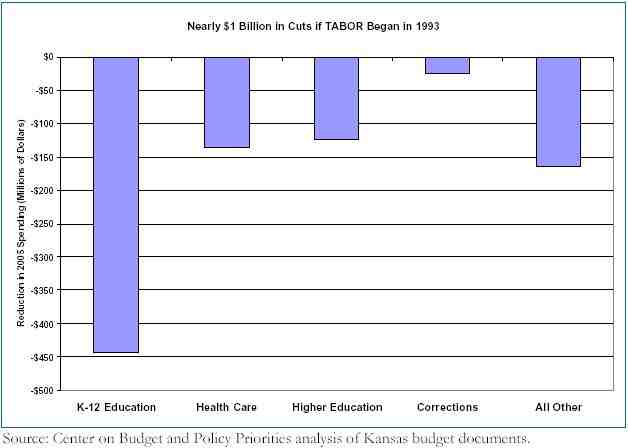

This report illustrates the potential magnitude and impact of such a cut. It looks at reductions in programs and services in FY 2005 if a TABOR limit had been in effect since FY 1993, the same year Colorado’s TABOR was enacted. For sake of discussion, it assumes that total expenditures would be reduced to the permitted level by cutting all areas of state government expenditures proportionally. Thus if K-12 education makes up one-half of the budget, it would receive one-half of the expenditure reductions.

While actual reductions likely would differ from this assumption, proportional reductions provide an indication of the types of reductions that would be required (Figure 1). Lesser cuts in any one area would have to be offset with deeper cuts in another. (See box below.)

FIGURE 1

Education

Reductions in state funding for K-12 education spending would have totaled $444 million in FY 2005. A reduction of this magnitude could have been accomplished in a number of ways.

- Kansas schools could have employed 10,000 fewer teachers in FY 2005. This would have raised the pupil-teacher ratio from 15.3 children per teacher to 23.4 children per teacher. The increase in the pupil-teacher ratio would move Kansas’ national ranking from the middle to the worst of the 50 states. Pupil-teacher ratios would continue to rise in subsequent years, as the funding reductions required by the limit grow.

- Kansas could have closed school 23 days early to save the $444 million in FY 2005. Again, fewer and fewer days of school would be affordable in future years as the limit would continue to pinch funding.

Health Insurance for Low-Income Households

State funding for Medicaid and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) would have been $135 million lower in FY 2005. Expenditures could be cut by reducing the number of people eligible to be covered by Medicaid or by reducing the type of services that are covered under the program. For reductions of this magnitude, both approaches would be necessary.

Moreover, for every dollar from own-source resources that Kansas expends on services in Medicaid, the federal government contributes an additional $1.56. Thus a $135 million reduction in state expenditures would also trigger the loss of $227 million in federal matching funds, for a total $362 million reduction in total payments to hospitals, physicians, and other health care providers to provide services under Medicaid or SCHIP (HealthWave).

A $362 million reduction could have been accomplished by making all of the following cutbacks.

- Dropping health insurance for all children enrolled in Kansas’ child health insurance program (HealthWave) — eliminating coverage for more than 50,000 Kansas children — would have reduced expenditures by about $55 million. The HealthWave (SCHIP) program covers infants with family incomes between 150 percent and 200 percent of the poverty line, children from 1 to 5 years of age with family incomes between 133 percent and 200 percent of the poverty line, and children 6 to 19 years of age with incomes between 100 and 200 percent of the poverty line. Children between age 6 and age 19 living in a family of three people, for example, would lose coverage if their family’s annual income was between $16,092 and $32,184. Many parents in that income range are not offered health insurance by their employers or cannot afford the steep premiums required to cover their children.

- Eliminating Medicaid payments to the statewide network of 29 Community Mental Health Centers would have cut expenditures by another $90 million. Community Mental Health Centers provided a range of treatments — medication management, crisis services, and ongoing support to help people live in their communities and homes — for 42,000 Kansans in 2005. Cutting $90 million in payments to the Centers would result in fewer services, fewer beneficiaries, or both.

- Eliminating funding for about two-fifths of Kansas’ home and community-based care services could have cut expenditures by $154 million, but would have adversely affected the 25,000 frail and disabled Kansans who depend on these services. The state of Kansas funds a variety of programs to enable different populations — children and adults with developmental disabilities, severe emotional disturbances, serious head injuries, and severe physical disabilities — to remain at home or in community settings (e.g. group homes, as opposed to institutions). Eliminating two-fifths of the funding for these programs would mean denying care to thousands of disabled Kansans and reducing the services to those remaining in the programs.

- Ending prescription drug coverage for half of adult Medicaid beneficiaries who are not also enrolled in Medicare could have cut expenditures by about $63 million in 2005.[1] This would end some prescription drug coverage for a wide range of classes of medications, including drugs for cancer, heart disease, mental illness, HIV, infections, etc. for tens of thousands of adults with serious health problems.

The Slow Squeeze of TABOR

This report shows the impact in FY 2005 of a TABOR that became effective in 1993. It looks over this long time period because the effects of a strict spending limit may take years to be felt fully.

Spending limits typically rise at a rate only modestly lower than the cost of providing services, perhaps a difference of one or two percentage points (Figure 2). Over time, however, the difference grows and compounds. A one- or two-percentage point difference every year can translate into a 13 to 26 percent gap over the course of a dozen years.

A state may react to the early years of a limitation by using accounting maneuvers and short-term deferrals. A state may push spending into future years, but that deferred spending can exacerbate the even tighter limits that lie ahead. A state may defer routine maintenance items, capital improvements, staff training, or other investments in infrastructure or workforce. Such changes may help balance the budget in the short run, but can be costly in the long run.

When public expenditures are investments, it may take many years for the harm from lack of investment to be evident. Much state spending is intended to have long-term impacts. Studies show, for instance, that early childhood spending has great benefits that do not begin to show up for many years. Infrastructure spending is another example. Failure to make expenditures now can have a negative effect on a state’s quality of life in future years.

These policies would have serious repercussions for thousands of Kansas children, people with disabilities and mental health problems, and other low-income adults. In many cases, such cuts would make people’s health problems worse and require them to use more expensive care. For example, cutting home and community-based care would force many into nursing homes or other institutions that are more expensive and cutting prescription drug coverage would make many people sicker and push them into hospital or emergency room care. Our estimates are conservative and do not include such offsetting increases in Medicaid costs that might arise if TABOR was adopted. If such offsetting adjustments were included, even deeper cuts would be required to accommodate the restrictive TABOR limits.

Corrections

State funding for correctional facilities would have been $25 million less than it actually was in fiscal year 2005. Cutting $25 million from the corrections budget would limit the state’s ability to follow current incarceration policies.

- For instance, a $25 million cut could require incarceration of about 1,300 fewer inmates — one out of every seven inmates in state corrections facilities in 2005. That may not be possible, however, because Kansas’ inmate population increased 30 percent in the past decade and is projected to increase by 15 percent in the next decade.

- Another way to view a $25 million cut is that Kansas could have cut 610 employees in the state’s eight correctional facilities. This reduction would constitute a 22 percent cut in the corrections workforce. A reduction of this magnitude in staff would have to be accompanied by the release of a substantial number of prisoners to avoid endangering the safety of the correction personnel and the inmates.

- As an alternative to spreading cuts across facilities, Kansas could close some of its correctional facilities. Kansas could achieve $25 million in savings by closing the Hutchinson correctional facility or the El Dorado correctional facility or both the Norton and Topeka correctional facilities. Of course, these savings would not occur if those prisoners were simply transferred elsewhere. These examples assume for the sake of illustration that the inmates would no longer be incarcerated.

Higher Education

Higher education — more precisely, the operating support of the state’s six public universities, nineteen community colleges, the University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC), Kansas State University Veterinary Medical Center (KSU-VMC), and Kansas State University Extension Systems & Agriculture Research Programs (KSU-ESARP) — would have faced a proportional share of state spending cuts in 2005 of a combined $123 million. Of this total, Kansas’ six public universities would have faced cuts of $76 million, community colleges cuts of $16 million, KUMC and KSU-VMC cuts of $21.5 million, and KSU-ESARP cuts of $9 million.

- To cut spending at the six public universities by $76 million, Kansas could have reduced its general support across the board and made up the difference through increases in undergraduate and graduate in-state tuition and fees. The increase would have to average $1,400 per year, which would represent a 33 percent increase in tuition and fees. Increases would range from 26 percent at Kansas State University to 47 percent at Fort Hays State University. These increases would be on top of tuition hikes ranging from 41 percent to 99 percent at the six public universities from 2000 to 2005.

- Rather than raising tuition across the board, the state could eliminate its entire general support for Wichita State University. To remain viable, Wichita State would have to charge the full rate to students, rather than the in-state rate.

- Alternatively, state universities could choose not to raise tuition but reduce instructional faculty instead to make up the $76 million funding shortfall. The state’s six public universities combined could reduce teaching staff by about 1,200, or 39 percent. This would increase course size, reduce course offerings, and likely lower the quality of instruction across the public university system in Kansas.

- To cut $9 million from the KSU-ESARP programs could be achieved by cutting one-third of the state appropriation for the state’s agricultural experiment station or by dropping one-half of state funding for the cooperative extension program in Kansas. Reductions of this magnitude would likely reduce the number of extension offices around the state, as well as hinder Kansas’ extensive research into making agriculture more efficient and safe.

Other

The service cuts detailed above in the areas of K-12, higher education, health care, and corrections would have achieved approximately $727 million of the $890 million in reductions required in FY 2005 if a TABOR had been effective since 1993. The other $163 million in cuts would have come from other areas of the budget, including agriculture, public safety, judicial, and youth service spending. To cut an additional $163 million from the budget, Kansas legislators could cut all state funding for the following.

- The entire state judiciary program ($91 million)

- Highway patrol ($31 million)

- Agriculture and natural resources, which includes money for food and water safety and environmental protection ($27 million)

Different Ways to Make TABOR Cuts in Kansas

The body of this report shows what would have happened if the cuts required by TABOR had been distributed proportionally across all areas of state government expenditures. For example, K-12 education makes up one-half of the state general fund budget, and thus would receive one-half of the required $890 million in expenditure reductions. Overall, every area of the budget would be cut by 19 percent.

Alternatively, Kansas policymakers might have chosen to protect funding for certain parts of the budget. In that case, other areas of the budget would have been cut much more deeply. Two alternative scenarios include holding K-12 funding harmless and holding K-12 and corrections funding harmless (Table 1). In the first alternative scenario, policymakers protect full funding for K-12 education, causing other areas to experience cuts of 38 percent.

In the second alternative, policymakers protect funding for K-12 education and corrections. In that case, all other areas would have to be cut by 40 percent.

| Table 1: | |||

| All Programs | K-12 Excluded | K-12 & Corrections Excluded ($ millions) | |

| K-12 | $444 | $0 | $0 |

| Higher Education | 123 | 246 | 260 |

| Education – Other | 13 | 25 | 27 |

| Medicaid | 135 | 269 | 285 |

| Other Health & Human Services | 74 | 147 | 155 |

| Public Safety – Corrections | 25 | 49 | 0 |

| Public Safety – Other | 37 | 75 | 79 |

| Agriculture & Natural Resources | 5 | 10 | 11 |

| General Government | 35 | 70 | 74 |

| Source: CBPP analysis of Kansas budget documents. | |||

Sources and Methodology

The base used in this analysis — Kansas General Fund Expenditures — is similar to the base proposed in recent Kansas TABOR proposals. The TABOR proposals exclude federal funds from the base. Kansas general fund expenditures totaled $4.7 billion in fiscal year 2005.

Estimated teacher reductions were calculated as the total K-12 expenditure shortfall divided by the average annual Kansas teacher salary plus compensation. Source: Kansas Department of Education, Salary Reports. Available at http://www.ksde.org/leaf/reports_and_publications/salary_reports/salary.htm .

Source (for current pupil-teacher ratios): Kansas Department of Education, Selected School Statistics. Available at http://www.ksde.org/leaf/reports_and_publications/selected_school_statistics/schl_stats.htm .

Estimated number of school days lost was computed by dividing the total annual operating expenditure for Kansas public K-12 schools by the number of school days per year (186). The result was an average cost per day of operating all Kansas public K-12 schools. Source: CBPP analysis of National Education Association data.

The estimate of $362 million in reduced Medicaid services is derived from adding $135 million in state expenditure reductions to the product of $135 million times the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid or SCHIP. The FMAP, which is based on a state’s per capita income, determines the federal dollar match for each dollar of state expenditure. In Federal fiscal year 2005, the Medicaid FMAP for Kansas was 61.01 percent and the rate for SCHIP was 72.71 percent.

All expenditure and enrollment data are from the Kansas Department of Social and Rehabilitation Services and the Kansas Department on Aging, Medical Assistance Report – Title XIX and Title XXI, June 2005. Available at http://www.srskansas.org/hcp/medicalpolicy/pdf/MAR.pdf.

Estimated inmate reduction calculated from average annual expenditure per inmate in state correctional facilities. Source: CBPP analysis of data in Kansas Department of Corrections, 2005 Corrections Briefing Report. Available at http://docnet.dc.state.ks.us/briefrep/2005BriefRept.pdf.

Inmate population estimates from Kansas Department of Corrections, 2005 Corrections Briefing Report, pages 33-36.

Estimates of staff reductions combine uniformed and non-unformed staff in the eight state correctional facilities. Uniformed employees comprise 71 percent of the total, so most of the employees cut would be front-line security personnel. Source: Kansas Department of Corrections, 2005 Corrections Briefing Report.

The total staffing and operating budgets of these facilities in fiscal year 2005 was approximately $25 million (Hutchinson), $21.2 million (El Dorado), and $24.3 million (Norton and Topeka). Source: Kansas Department of Corrections, 2005 Corrections Briefing Report.

The state of Kansas contributed 70 percent of its general fund support for higher education to six public universities in 2005 — University of Kansas, Kansas State University, Wichita State University, Emporia State University, Pittsburg State University, and Fort Hays State University. The state also provides funding for University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas State University – Extension Systems and Agriculture Research Programs, and Kansas State University Veterinary Medical Center, and community colleges. Tuition, salary, and enrollment data are from the Kansas Board of Regents, Data Book, May 2005. Available at http://www.kansasregents.org/download/universities/databook05.pdf.

End Notes

[1] Note that this example of a spending cut does not include any cuts to benefits for seniors and people with disabilities who are enrolled in Medicare. Under the new Medicare drug law, all Medicaid beneficiaries who are dually enrolled in Medicare will get prescription drug coverage under Medicare instead to Medicaid by January 2006. The state will be obligated to reimburse the federal government for a portion of the cost of covering those dual eligibles.

More from the Authors