- Home

- Food Assistance

- Testimony Of Zoë Neuberger, Senior Polic...

Testimony of Zoë Neuberger, Senior Policy Analyst, Before the House Education and the Workforce Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education

Thank you for the invitation to testify today. I am pleased to be able to speak to you about accuracy and integrity in the school meal programs and WIC. I am Zoë Neuberger, a Senior Policy Analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, where I have worked for 14 years. We are a Washington, D.C.-based policy institute that conducts research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic policy, policies related to poverty, and a number of social programs. The Center has no government contracts and accepts no government funds.

Part 1: The School Meal Programs

The National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs play a critical role in ensuring that our nation’s children are well nourished so they can learn and thrive. On a typical school day, these programs provide meals to more than 30 million children, nearly three in four of whom (72 percent) qualify for free or reduced-price meals due to their families’ economic circumstances. Despite improvements in the economy since the recession, many families continue to struggle to afford basic necessities, like food and housing, each day. Nearly 16 million children live in a household experiencing food insecurity; 8.5 million children live in a household where children, not just adults, experience food insecurity. The federal food assistance programs, including school meals, play an important role in shielding children from hunger.

Hungry children can find it hard to focus and to perform in the classroom. School meals can help make their time in school more successful. Research shows, for example, that eating breakfast at school improves student achievement, diet, and behavior. In addition to helping meet children’s immediate needs, the school meal programs yield longer-term benefits. Low-income children are more likely to face chronic health and developmental difficulties, which can have lasting negative consequences. Receiving healthy meals at school can mitigate the risk.

Making sure that eligible low-income children can access breakfasts and lunches, which support a successful school day and healthier lives, is the most fundamental goal of the school meal programs. We recommend that the Committee place top priority during the reauthorization process on strengthening the programs to ensure that they continue meeting the needs of eligible low-income children.

| Table 1: School Breakfast Program 2014-2015 Reimbursement Rates* | |

|---|---|

| Meal Category | Rate** |

| Free | $1.62 |

| Reduced Price | $1.32 |

| Paid | $0.28 |

|

*These rates apply in the contiguous states. For the higher rates for Alaska and Hawaii, see http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/cn/NAPs14-15chart.pdf. **Schools that serve more than 40 percent of their lunches to children who qualify for free or reduced-price meals (among other criteria) receive an extra 31 cents in “severe need” reimbursement for each free or reduced-price breakfast. |

|

At the same time, the programs must also endeavor to ensure that federal meal subsidies are provided only for meals that meet program requirements and only to children who qualify for them. Delivering the correct benefit to each child is a fundamental aspect of sound stewardship and a core responsibility of the programs. Moreover, public support of these very important programs is compromised if federal funds are not used as intended due to problems with program administration and operation.

| Table 2: National School Lunch Program 2014-2015 Reimbursement Rates* | |

|---|---|

| Meal category | Rate** |

| Free | $2.98 |

| Reduced Price | $2.58 |

| Paid | $0.28 |

|

* These rates apply in the contiguous states. For the higher rates for Alaska and Hawaii, see http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/cn/NAPs14-15chart.pdf. **School districts that serve more than 60 percent of their lunches to children who qualify for free or reduced-price meals receive an extra 6 cents per meal for each meal category. Each meal, regardless of category, also receives 24.75 cents worth of commodities from the federal government. |

|

My testimony will address this issue in four sections: a review of the school meal eligibility determination and counting and claiming processes, a discussion about the kinds of errors that occur during these processes, a review of the efforts in the 2004 reauthorization law to address errors, and a framework for assessing error-reduction policy proposals, including steps already taken as well as recommendations for areas to explore to make further progress on improving program accuracy.

Eligibility for Federal School Meals Subsidies

Generally, public or nonprofit private schools may participate in the school lunch or breakfast program. The school districts that choose to take part get cash subsidies from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for each meal they serve; they also receive some foods for each lunch they serve. In return, they must serve meals that meet federal requirements and must offer free or reduced-price meals to eligible children.

Any child at a participating school may purchase a meal through the National School Lunch Program or the School Breakfast Program. Children from families with incomes at or below 130 percent of the poverty level are eligible for free meals. Those with incomes above 130 percent and at or below 185 percent of the poverty level are eligible for reduced-price meals, for which students can be charged no more than 40 cents for lunch or 30 cents for breakfast. (For the period July 1, 2014, through June 30, 2015, 130 percent of the poverty level is $31,005 for a family of four; 185 percent is $44,123.) Children from families with incomes over 185 percent of poverty pay a full price, though their meals are still subsidized to some extent. Local school food authorities set their own prices for full‐price (paid) meals but must operate their meal services as non‐profit programs.

Most of the support USDA provides to school districts through the school meal programs takes the form of a cash reimbursement for each meal served. School districts receive no additional federal funds for administrative costs. Tables 1 and 2 show the current (July 1, 2014 through June 30, 2015) basic cash reimbursement rates for breakfasts and lunches.

Eligibility Determination Process

Schools must determine which subsidy category students qualify for through an eligibility process. A single determination is made for breakfast and lunch. Federal rules govern eligibility determinations, although they are operationalized in different ways across the roughly 100,000 schools that participate in the meal programs. These schools are spread across over 13,000 school districts, which range from small rural, or charter, districts with a single school to large school systems that serve hundreds of thousands of students daily.

Certification

When possible, children are approved for free meals based on information from another program, a process known as “direct certification.” Children receiving Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps) or cash assistance benefits, for example, can be directly certified based on a data-matching process between a student database and the state’s human services database. Children who are homeless can be directly certified if identified by the district’s designated “homeless liaison.” Once approved, children remain eligible for free meals for the rest of the school year, even if household circumstances change.

Children who are not directly certified and whose parents seek help from the free or reduced-price meal programs must apply. The application is often distributed as part of the package of enrollment forms at the start of the school year. Parents typically complete these forms on their own, without assistance. If they have a question about whether to include a certain kind of income, what “gross” income means, or whether to list a relative who’s staying with them, clarifications may not be readily available. They could try to find the instructions online or seek out someone at the school to help, but they may instead do their best to provide the information they believe is asked for. If they make a mistake, it would be considered a “household error” that may affect eligibility.

Once a family submits an application, someone at the school or district must review it to calculate household size and income and compare them to federal poverty guidelines. Reviewing applications is rarely a school district employee’s expertise or full-time job, as meal applications are submitted and processed primarily in the weeks just before the school year starts. Often, school officials process applications for just a small portion of the year while juggling many responsibilities. If the data from a paper application has to be entered into an electronic system, data entry errors can be made. When adding up income for multiple sources and multiple people, math errors can be made. More and more schools use electronic systems, which reduce opportunities for such errors, but many families still submit paper applications, and in some places that is the only option.

Verification

Once a child is approved based on an application, he or she receives free or reduced-price meals for the remainder of the school year unless the application is selected for eligibility verification. Under the annual verification process, a small sample of applications is selected and the school district must make sure that a correct determination was made based on the information on the application; then, the district confirms the child’s eligibility again by obtaining documentation from a third party or the family. Verification is an important part of the eligibility process. It helps reinforce to districts and families the importance of accurate eligibility determinations. And, when the verification process catches errors, it can provide useful information to program operators about potential deficiencies in application and review processes.

If the school district cannot verify eligibility from a third-party source such as the state’s human services office (which can inform the school whether the child is enrolled in SNAP, cash assistance, or Medicaid), it must contact the household to ask for documentation of the child’s eligibility. If the household does not respond, the child’s free or reduced-price meals are terminated. If the household provides satisfactory documentation, the district uses it to assess whether the child may continue to receive free or reduced-price meals.

Usually the verification sample is 3 percent of approved applications (capped at 3,000 in larger districts), selected from applications where monthly income is within $100 of the limit for free or reduced-price meals. The law targets those with reported income close to the limit because these applications are considered error prone. The process also is designed to encourage districts to obtain documentation from households. This is important because:

- The goal is to verify households’ eligibility by reviewing their circumstances.

- Some households may need assistance to understand the verification process.

- Children in households that do not reply lose access to free or reduced-price school meals.

To encourage districts to obtain verification rather than terminate benefits to households, districts that successfully lower their non-response rate can choose the next year between a smaller sample size and selecting the sample at random from all approved applications, either of which is easier than the standard approach.

For the 2013-2014 school year, 35 percent of families selected for verification did not respond and their children stopped receiving free or reduced-price meals, regardless of whether they were actually eligible. The initial eligibility determination was confirmed for 38 percent of verified applications, changed for 24 percent to reduce the subsidy level, and changed for 2 percent to raise the subsidy level. It is important to note that these rates cannot be applied to the whole program because the verification system focuses on the most error-prone certifications.

In addition to this standard annual verification process, school districts must seek documentation of eligibility from applicants if they have reason to believe that the information on a household application is incorrect. This may occur, for example, if a parent employed by the school district does not list his or her correct income information or if the family has completed another form and provided different information. This is called “verification for cause.”

The Government Accountability Office’s (GAO) 2014 report on school meal verification, USDA Has Enhanced Controls, but Additional Verification Could Help Ensure Legitimate Program Access, and this week’s report from USDA’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) on its audit of the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs, noted that some school districts do not use verification for cause because they are uncertain about the circumstances under which it is permitted. USDA issued guidance in February 2012 clarifying that school districts may use data on the salaries of district employees to identify applications with questionable income data for purposes of conducting verification for cause and added examples of appropriate circumstances in which to conduct verification for cause in the August 2014 Eligibility Manual for School Meals.

If a child’s free or reduced-price meals are terminated as a result of verification, the family can reapply at any time but must provide income documentation along with the application.

Counting and Claiming Process

As noted above, in order for a meal to qualify for a federal subsidy, the school must ensure that the meal meets basic federal nutrition standards, count the meal to obtain reimbursement, and identify whether the child qualifies for the free, reduced-price, or paid subsidy rate. If the child is in the paid category, the school’s meal fee is also collected. The counts of children by meal category must be tallied across schools and then submitted by the district to the state child nutrition program office for reimbursement. This aspect of the program is called the “counting and claiming process.” It is another area where errors can occur.

Most of the aforementioned activities typically occur at the “point of service,” which may be a cafeteria checkout line or the classroom. This process can be rushed. In many districts, students have less than 30 minutes for lunch, which includes time to wait in line, select their food, stop at the register, and eat. In some districts, the person operating the register may have little training or support. Errors in this area, known as “operational errors,” are therefore not surprising. Research show that they tend to be concentrated in a limited number of school districts.

Overall, the processes for making eligibility determinations as well as counting and claiming meals for correct reimbursement aim to maximize program accuracy while being navigable for families and administratively feasible for schools and cost-effective for the program.

Assessing Errors in the School Meal Programs

USDA oversees the annual verification process and monitors school meal program accuracy. Every few years, USDA conducts the Access, Participation, Eligibility and Certification (APEC) study; the one released this week examined the 2012-2013 school year and built on one for the 2005-2006 school year. This study entails a comprehensive review of program accuracy with respect to eligibility and reimbursements. Household interviews are conducted to determine whether students were certified for the right category and whether the verification process resulted in needed corrections. Monitors observe cafeterias to determine whether only meals that meet nutrition standards are reimbursed and to determine whether schools count and claims meals accurately. The report helps make transparent the areas where errors occur and the ways in which state child nutrition and district officials can help schools improve accuracy.

The APEC report serves as a comprehensive audit of how well the program is managing each of these steps. In addition, it helps clarify the types of errors that occur:

- Certification errors that result from household errors, including math errors, unintentional mistakes, and deliberate misreporting;

- Certification errors that result from school clerk errors, including data entry errors, math errors, and fraud; and

- Counting and claiming errors, including reimbursements for meals that do not meet nutrition standards and math errors when tallying meals across a district or state.

In each category, APEC disaggregates overpayments and underpayments, which allows for a calculation of net costs and helps target interventions. Although the overall extent of improper payments remains consistent with the levels found in the earlier study, the share of children approved for the wrong meal category has been reduced slightly and errors associated with incorrectly tallying meal counts have been greatly reduced.

Certification Errors

Certification errors are mistakes by school staff or parents that cause children to receive higher or lower subsidies than they qualify for.

Household errors can result when a parent reports take-home pay net of withholding, instead of gross pay, on a school meal application or calculates a household’s monthly income by multiplying its weekly income by 4 instead of 4.33 (the number of weeks in the average month). Consider a household of four with weekly earnings of $610. Calculating their monthly income by multiplying that figure by 4 would result in $2,440, whereas multiplying by 4.3 would result in $2,623. The former monthly income qualifies for free meals; the latter qualifies for reduced-price meals.

Similarly, forgetting to include a household member, such as a grandparent, on an application can result in overstating the household’s income relative to the poverty line. As a result, the children in the household might get a lower subsidy than they qualify for.

Household errors also include intentional misstating of income in order to qualify for free or reduced-price meals. There is often no way to distinguish an accidental misstatement of income from a deliberate one, but it is important to recognize that most errors are likely unintentional. Nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of the underpayments associated with certification errors that APEC found for the 2012-2013 school year resulted from incorrect reporting by households. Because these households are unlikely to have deliberately reported information that reduced their own benefits, this finding highlights some parents’ difficulty in understanding school meal applications.

Examples of administrative certification errors by school districts include transposing a number when entering data from a paper application into a data management system, applying the wrong income threshold, and making a math error when combining income obtained from multiple sources at different frequencies.

Operational Errors

While the focus of the May 2014 GAO report and this week’s OIG report is the eligibility determination process, it is important to keep in mind that eligibility is only one source of program error. Operational errors are administrative mistakes by cashiers or school administrative staff that result in miscounts of the number of subsidized meals served in a given category. Typical examples include counting a meal that does not meet the nutritional requirements for reimbursement or incorrectly adding up the number of meals served at all schools in a district or state. The kinds of training and administrative oversight needed to prevent errors like these are very different than the kind of policy responses that can reduce certification error.

Operational errors can happen when the cafeteria is crowded and there is limited time to move many students through. There can also be trade-offs between reducing errors and reducing plate waste. If the server puts required foods on the plate with no student choice, there’s less room for error and the line moves more quickly. Children, however, may not eat as much as they would if they had some choice and may throw away unwanted items. Likewise, putting robust checks in place at the register to ensure that each meal is categorized and counted correctly can cause the line to move more slowly, leaving children with less time to eat or necessitating that districts extend the lunch period.

Operational errors are also more likely in school systems that have less technological capacity and rely more heavily on paper processes. If the cashier has to check off each student on a paper list of all students and then make sure the meal meets nutritional standards, the process is more time consuming and error prone than if all students enter their personal account number (which tracks meal categories) into an automated system while the cashier checks the meal. Similarly, adding up the number of meals served by category across schools and days via a paper system creates opportunities for simple math errors. Minor mistakes can also occur in small schools when the cafeteria worker misses a day of work and someone else, often a front-office staffer or the principal, steps in to check out students during the lunch period.

To be clear, most schools count and claim meals correctly every day. But it is important to understand how the design and staffing of the system across 100,000 schools each day can contribute to honest errors.

Underpayments and Overpayments

It is also important to keep in mind that improper payments include underpayments as well as overpayments. The APEC study found that as a result of certification errors, 12 percent of children who applied for school meals received higher subsidies than they were eligible for. But certification errors also resulted in 8 percent of applicants getting lower subsidies than they were eligible for, causing them to miss out on needed benefits. And, the improper denial rate is very high. More than one-quarter of the children who were denied free or reduced-price meals should have received them.

While underpayments have the negative consequence of needy children not getting the meals for which they are eligible, they do lower federal costs. To identify the cost of errors to the federal government, one must subtract underpayments from overpayments to obtain a net figure. The net cost to the federal government of the errors studied was about $1.4 billion.

Making Sense of Different Errors

Adding up the different kinds of improper payments does not clarify the best ways to improve program accuracy and accountability. Different types of errors require different interventions. A math error by a school official requires a different response that a math error by a family. An antiquated paper application system requires a different response than a cashier who isn’t properly trained to identify meals that meet federal standards. And different kinds of responses have widely different costs.

Errors that result from design or operational flaws, such as confusing forms or lack of time for meals, may be addressable through modest design improvements that may not cost much or through technical assistance on best practices. Errors that result from poorly trained staff or lack of automation can require significant investments. Errors that result from individuals seeking to defraud the program are likely specific to small numbers of individuals and typically require more targeted interventions.

To prioritize, it’s important to look at the magnitude and scope of different kinds of error. Policymakers also must consider how much in new funds it makes sense to invest in error reduction and whether those resources are best devoted to error reduction at all. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ focus is to develop error-reduction strategies that do not cause eligible low-income children to lose free and reduced-price meals, do not overly burden schools that are already stretched thin trying to educate children, are effective and adequately financed, and do not cost more than they save.

Efforts in the 2004 Reauthorization to Address Error in the School Meal Programs

As Congress began developing the reauthorization legislation eventually enacted in 2004, some policymakers were concerned that ineligible children were being approved for free or reduced-price meals. Some suggested mandating that schools verify a larger share of approved applications. School officials, in turn, were deeply concerned at the possibility of new unfunded mandates and many believed that such efforts would cause eligible low-income children to lose access to school meals.

Research had consistently shown that a substantial portion of families that do not respond to the verification notice are actually eligible for free or reduced-price meals. They may fail to respond because they don’t receive the notice, cannot read it, do not understand it, or are reluctant to share income information with school staff. We also worry that parents may not understand the consequences of failing to respond — particularly if their children do not inform them that they have lost eligibility for free or reduced-price meals or if the school begins charging parents but doesn’t send home a bill for several weeks.

To inform the reauthorization debate, USDA conducted several studies on the impacts of expanded verification. It briefly described its findings in NSLP Certification Accuracy Research — Summary of Preliminary Findings in 2003 and several volumes detailing each study. We summarized them in a 2003 report What We Have Learned from FNS’ New Research Findings about Overcertification in the School Meals Programs. As with GAO’s May 2014 report and this week’s OIG report, these studies did not involve nationally representative samples, but their findings can inform policy development.

- Expanded income documentation requirements did not reduce the extent to which ineligible children were certified to receive free or reduced-price meals.

- Expanded income verification requirements led substantial numbers of eligible children to lose free or reduced-price meals. In metropolitan areas, children in more than one of every three families selected for income verification lost their free or reduced-price meal benefits despite being eligible. For every ineligible child that lost benefits as a result of verification, at least one eligible child lost benefits as well.

As a result of these findings, Congress wisely focused on reducing opportunities for error and strengthening the verification process, rather than expanding verification or income documentation. In the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004, the focus of verification sampling was shifted to error-prone applications (those close to the income limits for free or reduced-price meals). School districts were permitted to use Medicaid data to verify eligibility.

School districts were also required to follow up with households that do not initially respond to the verification notice. Despite an increased focus on obtaining responses to verification notices, more than one in three families selected for verification (35 percent) for the 2013-2014 school year did not respond. While some were likely ineligible, the research indicates that many eligible families likely lost access to school meals or reapplied following the verification process, which creates more paperwork for schools.

These findings also reveal why the recommendation in this week’s OIG report to require income documentation at the time of application is unlikely to effectively prevent certification errors but would substantially increase the workload for school districts and result in eligible low-income children not applying for free or reduced-price school meals. USDA found that requiring income documentation at the time of application, which was then used to certify students, did not reduce the extent to which ineligible children were approved for free or reduced-price meals, which is the main argument in favor of this policy noted in the OIG report. But having to gather such documentation did deter eligible families from applying.

Even if districts did not use the documentation unless the application was selected for verification, as the OIG report recommends, collecting, managing, and storing large quantities of new documentation would create a significant new workload for school districts. They would need a process for maintaining documents submitted with applications, which are currently usually only a single page. They would need more file storage capacity or an electronic scanning and document management system. They would also need to ensure that sensitive personal information, such as that on pay stubs, was kept securely and that all confidentiality protocols were followed.

Framework for Strengthening Integrity in the School Meal Programs

We encourage the Committee to consider ways to continue supporting a culture of accountability and continuous improvement in the school meal programs at every level of administration — federal, state, and local. Given what we know about the programs’ role in addressing child hunger, the challenges for resource-constrained schools in determining eligibility and claiming reimbursements, the extent of errors in different aspects of the program, and previous efforts to improve program accuracy, there is ample information to guide new initiatives in this area.

USDA’s APEC report shows that there is significant room to improve program accuracy — and that school districts and state child nutrition programs can do so without compromising access for the most vulnerable children or imposing unreasonable burdens on schools and states. We know this because many districts and states have strong track records regarding certification and operational errors. Congress and USDA can work to better understand what distinguishes them from places that struggle with errors. Policymakers can use this information to equip the program at all levels with the resources and oversight needed to continue improving.

These efforts will likely require new investments to build administrative systems that prevent and catch errors, help train the hundreds of thousands of school food service and school district employees that oversee program operations, identify sound practices that can be exported from one successful system to another, and experiment with new methods of identifying and curbing errors and fraud.

We strongly recommend that that any new policy or effort to reduce improper payments be assessed against the following criteria:

- Does it have a demonstrated impact on reducing error? We can learn a great deal from districts and states that are successful in reducing errors and, where possible, export their practices to others.

- Will it maintain program access for the most vulnerable children? School meals are critical to children’s immediate needs and long-term development. Strengthening program integrity must not come at the expense of ensuring that every low-income child receives needed nutrition.

- Is it feasible? High-quality information technology systems or reduced staff turnover due to competitive pay may have helped some districts lower error rates but may be too costly for all districts to adopt. Simplifying the school meal application with helpful instructions may be a much better solution to confusing applications than purchasing an expensive new online system. Likewise, a more time-consuming documentation or verification system might catch more errors but require school staff district staff to spend considerably more time on school meal eligibility determinations at the expense of other educational priorities.

- Is it cost-effective? The cost of an ineligible child getting free lunches and breakfasts for a school year is between $700 and $800; efforts that target infrequent problems could easily cost more than they save. Providing local school food officials with a clear message that program accuracy is important, that it will be measured, and that state child nutrition officials and USDA will support local program managers in their efforts to implement needed improvements, builds a stronger system in the long run than punitive policies.

Fortunately, the APEC report and recent efforts to address program errors offer a strong menu of ideas to explore as a part of reauthorization.

Reducing Opportunities for Error in the School Meal Programs

Over the last decade, the school meal programs have made increasing use of highly accurate data from other programs, abetted by provisions in the last two reauthorization laws. Relying on such data reduces the number of school meal applications, often paper applications, that schools have to certify and verify. This reduces opportunities for error and gives school personnel more time to focus on the applications submitted through the traditional process.

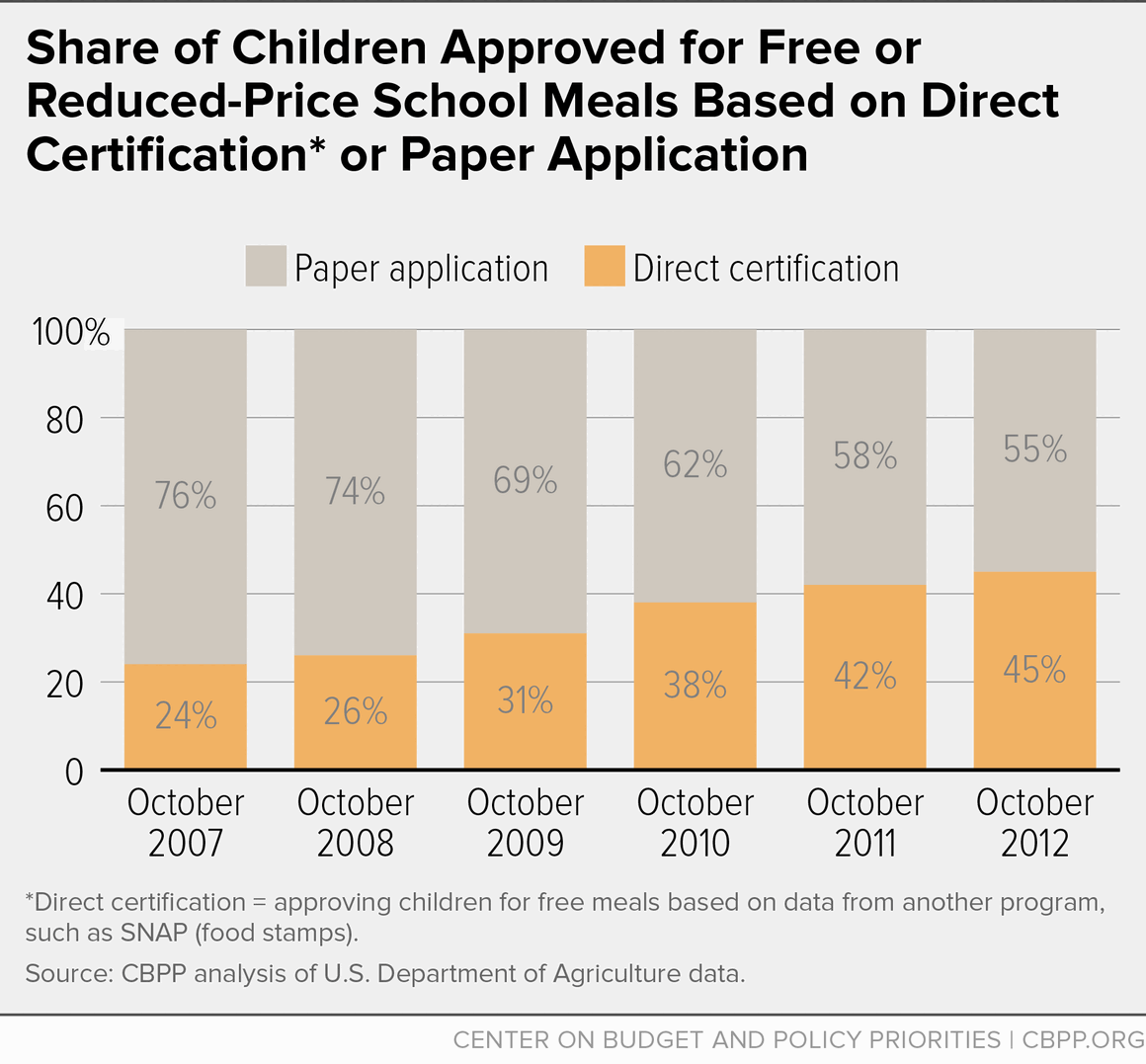

- There has been steady improvement in and expansion of the use of “direct certification” — approving children for free meals based on highly accurate data from another program, the largest of which is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps). Direct certification improves the accuracy of eligibility determinations while reducing paperwork for schools and families. For the 2007-2008 school year, 76 percent of children approved for free or reduced-price meals were approved based on a paper application. As shown in Figure 1, by the 2012-2013 school year, the share of paper applications had fallen to 55 percent. As a result, even though 4 million more children were approved for free or reduced-price meals that year due to the recession, school districts processed applications for 2.5 million fewer children.

- A new option known as “community eligibility” allows schools with large concentrations of low-income students to be reimbursed on the basis of the share of students that are directly certified if they serve all meals at no charge, which eliminates the need for meal applications altogether and thereby greatly simplifies program administration. This new option builds on decades-old options under the National School Lunch Act to allow high-poverty schools to serve all meals at no charge. As a result, these schools have fewer opportunities for administrative errors and can shift resources from paperwork to improving their program.

Additional School Meals Program Integrity Measures

Strengthening program rules so that school meal subsidies flow to meals and children that qualify for them is important. Such changes must meet the criteria described above by responding to specific issues without impeding low-income children’s access to free or reduced-price meals or overly burdening schools, which already face many challenges when educating low-income children. Cost and cost-effectiveness are also important considerations. The funds needed to equip tens of thousands of schools with modern technology for online applications, access to third-party data sources, automated checkout lines, quality counting and claiming software, and training either require new federal investments or the cost would have to be covered within the meal budget in many districts.

Over the last decade, many carefully designed program integrity measures have been implemented. In addition to the 2004 changes to the verification process described above, the following well-tailored measures strengthen program integrity without impeding access or overly burdening schools.

Improving Direct Certification

As explained above, direct certification has been improved and expanded to reduce opportunities for certification error by reducing the number of children approved for free meals based on an application.

- States or school districts are required to conduct a minimum of three electronic data matches using SNAP records each year, with more frequent matching encouraged.

- USDA must issue an annual report analyzing state performance and highlighting best practices.

- The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 established performance benchmarks, requiring states to directly certify 95 percent of the school-age children in households receiving SNAP benefits.

- States that do not meet the direct certification performance standards are required to develop a Continuous Improvement Plan (CIP) identifying action steps, a timeline for implementing them, and measures to assess progress.

- Direct certification improvement grants have been available to help states improve their data-matching hardware or software and train school districts on direct certification.

- High-performing states and those that made substantial improvements in their direct certification performance have received bonus awards.

- Seven states participate in a demonstration project permitting them to use Medicaid data to directly certify eligible low income-children for free school meals.

Simplifying the School Meals Application to Reduce Errors

While applications must follow program rules and USDA makes a model available, school districts are not required to use a particular form. We have conducted several thorough reviews of applications over the last decade and found that many are confusing. They may be incomplete or imply that parents need to provide information that is not necessary. They are rarely translated into languages other than Spanish, even though USDA provides translations in 33 languages. The instructions are often in a separate document and use legalistic language that is hard to understand. As a result, families may make mistakes because they simply do not understand what is being asked of them and school nutrition staff may spend time following up with families to explain the forms.

It is important to help school districts improve their applications so families can understand them and staff can obtain the information they need. To reduce incidents of certification error due to household misreporting of information, USDA is improving its model application.

- Just last month, USDA released a newly designed prototype meal application, which includes clearer instructions on the form itself; separate instructions provide specific details about more complicated issues like the kinds of income that must be reported. The new design is also meant to reduce mistakes by school nutrition staff when reviewing applications. The new design will likely be broadly adopted, since many state model applications and large district applications have closely followed USDA’s prototype in the past. USDA plans to assess understanding of the new application by households and school nutrition staff once it is in use in order to continue to improve it.

- USDA has announced plans to develop a prototype electronic application, which has never been available. Existing electronic applications do not take full advantage of the ways in which the electronic environment could simplify the application and provide more detailed instructions to elicit accurate information. By developing a prototype, USDA can reduce household errors. Moreover, states could incorporate the new electronic prototype into online application systems that offer the potential for prompt comparison to other data sources to identify inconsistencies.

Strengthening Districts with High Rates of Certification Error

School districts with high rates of incorrect eligibility determinations warrant more support and intervention from state child nutrition staff and USDA. To reduce instances of certification error due to administrative mistakes, oversight has been strengthened.

- Under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, school districts identified by state child nutrition officials as having high error rates regarding eligibility determinations based on applications must conduct a second, independent determination before approving any household for free or reduced-price meals. This is a targeted intervention designed to prevent errors from resulting in improper payments.

- USDA has established an Office of Program Integrity for Child Nutrition Programs, which will develop and test policies and practices to strengthen program integrity. This office is involved in improving USDA’s prototype application. Dedicating federal staff to reducing program error sends a strong signal to state and local school food administrators that USDA values a culture of accuracy and continuous improvement.

Identifying and Addressing Operational Error

Errors that result from claiming reimbursement for meals that do not meet federal standards are concentrated in a relatively small number of school districts and can be addressed through targeted training and technical assistance. But maintaining low levels of operational errors amidst changing program rules and frequent staff turnover requires a commitment to ongoing training and oversight. Over the last decade, investments have been made in this kind of continuous improvement, which keeps counting and claiming error rates low in most places.

- As a result of the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004, state child nutrition staff were required to conduct reviews focused solely on strengthening administrative processes in selected school districts with, or at risk of, high error rates. Under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, these administrative reviews were incorporated into a more rigorous, risk-based review process that addresses all aspects of program management. Reviews are now conducted more frequently (every three years rather than every five years), the areas to be reviewed have been updated, and USDA is developing ways to use the results of the reviews to strengthen program management.

- Under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, USDA developed new professional standards with regard to continuing education and training for school nutrition staff. One goal of the new standards is to reduce program error and improper payments.

- The Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 established a $4 million annual grant program focused on reducing administrative error. USDA distributes the funds through a competitive process to states for technology improvements and to identify, review, monitor, and train school districts that have demonstrated a high level of, or a high risk for, administrative error. For example, the Kansas Department of Education received a $1.3 million grant to update its online claiming and review management system and improve staff training regarding counting and claiming accuracy. These grants are likely partly responsible for the decrease in meal aggregation errors found in the recent APEC study.

Future School Meal Programs Improvements

The reauthorization process offers an opportunity to identify new ways to support school districts’ efforts to reduce errors in the school meal programs and build a shared culture of accuracy and accountability. Once we have had time to review the APEC study, just released this week, more thoroughly, it may point the way toward additional promising ideas. In the meantime, we recommend that the Committee consider the following ideas for further exploration:

- Electronic applications. Electronic applications are becoming more prevalent in the school meal programs. In 2011, about one-third of the 100 largest school districts provided an electronic application; by 2013, about two-thirds did. But existing applications do not take full advantage of the opportunity to simplify the process, provide more detailed instructions as needed, or check income data against other sources. USDA’s plan to development a model electronic application is a very promising way to improve the quality of electronic applications and the information parents provide on them. States could then explore whether electronic applications could be linked to other data sources to pre-populate certain fields or flag inconsistent information. Congress may also want to provide funding to support districts that cannot afford to build an online application platform on their own. With small grants, many districts might be able to adapt USDA’s electronic form and software in lieu of building or buying new applications.

- Improved direct certification of SNAP and TANF recipients. Children who receive SNAP or Temporary Aid for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance benefits who were not certified based on the direct certification data-matching process can submit an application with the household’s SNAP or TANF case number. As direct certification improves, the number of applications that include a case number is shrinking. Nonetheless, for the 2012-2013 school year there were 1.7 million children approved based on applications with case numbers. The May 2014 GAO report recommends verifying or reviewing a sample of these applications. Because all of these applications should have been directly certified and there should be fewer of them each year, it does not make sense to establish a new verification process focused on them. A better approach would be to explore whether school districts should be required to develop a process for attempting to directly certify such applications, which some districts already do, by working with a state or local human services agency. If that process reveals that the human service agency cannot confirm benefit receipt, then the application would meet the existing criteria for verification for cause and the school district could follow up that way.

- Expanded direct certification. As noted above, seven states (California, Florida, Illinois, Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania) are participating in a demonstration project that allows them to use Medicaid data to identify children eligible for free school meals. This option should be available to all states and school districts. Approximately 3.5 million children receive Medicaid but not SNAP or TANF cash assistance and have income low enough to qualify for free school meals. Making use of the robust eligibility determination already made by Medicaid would allow more children to be directly certified, further reducing the number of applications that school districts must review and verify.

- Improper denials. USDA’s APEC study found that one in four applications that were denied free or reduced-price meals should have been approved based on actual household circumstances. To date, verification has focused on correcting improper approvals for benefits. It is equally important, if not more so, to correct improper denials. Methods of checking a sample of denied applications should be explored.

- Data-matching to determine the verification sample verification. The 2004 reauthorization law encouraged school districts to “directly verify” eligibility using data from other public benefit programs and permitted the use of Medicaid data for this purpose. If eligibility can be confirmed based on data from these programs, the school district does not have to contact the household, which reduces the paperwork burden for schools and low-income families. But these data are used once the verification sample has been selected. GAO’s May 2014 report recommended using data-matching to select applications for verification. While this could prove to be a more effective approach than the current focus on applications near the income limits for free and reduced price meals, it needs to be explored further. Promising sources must be identified that have data recent enough to match the time period when the application was completed and can successfully be matched using the data elements available on meal applications. The cost-effectiveness of verifying applications based on discrepancies of various sizes would need to be explored. And policies would need to be developed to ensure that children do not lose benefits unless their parents have been given ample opportunity to explain or document any discrepancy. Once these factors have been explored, policy makers could consider whether to expand the share of applications verified using this approach, as recommended by the GAO, which would increase the workload for school districts, or instead substitute it for the current focus on error-prone applications.

- Expanded direct verification. School districts are already permitted to use data from SNAP, Medicaid, and TANF to verify eligibility without having to contact households. Additional data sources could be explored, such as state tax or wage databases. For example, a pilot could be conducted in a large district with the technological capacity to explore the feasibility of linking these data bases with student databases or school meal program systems and, if this is possible, whether the share of applications that can be directly verified can be increased. Data-matching, however, is a complex process. Often the information available from third-party sources, such as state wage databases or private wage data sources, is not available in formats that are easily translatable to the school meals household. School staff would need to be trained on the implications of accessing private data (including having appropriate security measures in place) and using the data appropriately in a school meal programs context.

- Verification for cause. Both the May 2014 GAO report and this week’s OIG report highlighted the limited use of verification for cause in some districts and recommended that USDA develop further guidance regarding its use. Further guidance would help school districts understand when it is appropriate to conduct verification for cause and provide safeguards to ensure that it is not used in a discriminatory manner. During the 2013-2014 school year, about 1,600 school food authorities out of nearly 20,000 that submitted data to FNS made use of verification for cause. Other districts could certainly benefit from using verification for cause in appropriate circumstances. It is worth exploring, for example, whether it would be beneficial to routinely verify for cause any application submitted by a household that was found to have misreported income during the prior year’s verification process, as recommended in the OIG report. It would not be wise, however, to routinely verify for cause any application for which benefits were reduced or terminated as a result of the verification process, as further recommended in the OIG report. Of the students whose benefits were reduced or terminated as a result of the 2013-2014 verification process, three in five lost benefits due to non-response, not because the school district found misreporting.

- Data mining. It is worth exploring whether data mining, a process by which statisticians look for unusual patterns in data, could be used to identify potential fraud by finding patterns in applications; in a district that houses applications in an automated system, for example, it might be possible to identify applications that appear suspicious. Again, this approach could be tested in a large district with both a school meal data system into which income information is entered and the technological capacity for data mining.

Part 2: The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, popularly known as WIC, provides nutritious foods, counseling on healthy eating, breastfeeding support, and health care referrals to more than 8 million low-income women, infants, and children at nutritional risk.

Infants and very young children can face lifelong cognitive and health consequences if they don’t get adequate nourishment. WIC aims to ensure that pregnant women get the foods they need to deliver healthy babies and that those babies are well-nourished as they grow into toddlers.

Extensive research shows that WIC contributes to positive developmental and health outcomes for low-income women and young children. In particular, WIC participation is associated with:

- Healthier births. Women who participate in WIC give birth to healthier babies who are likelier to survive infancy.

- More nutritious diets and better infant feeding practices. WIC participants now buy and eat more fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy products, following introduction of new WIC food packages more closely aligned to current dietary guidance.

- Stronger connections to preventive health care. Low-income children on WIC are just as likely to be immunized as more affluent children, and are likelier to receive preventive medical care than other low-income children.

- Improved educational prospects. Children whose mothers were on WIC while pregnant scored higher on assessments of mental development at age 2 than similar children whose mothers were not, and they later performed better on reading assessments while in school.

- Healthier neighborhood food environments. Improvements to the WIC food packages in recent years have contributed to healthier food environments in low-income neighborhoods, enhancing access to fruits, vegetables, and whole grains for all consumers regardless of whether they participate in WIC.

WIC is not meant to provide the full array of foods that a family with young children needs. Instead, it provides vouchers for specific types of foods chosen through a rigorous science-based process because they tend to be lacking in the diets of low-income women and young children. USDA revised the WIC food packages in 2009 based on recommendations from the Institute of Medicine, which is conducting a new review of WIC foods to recommend any needed updates.

While WIC promotes breastfeeding as the optimal feeding choice for infants, it provides infant formula to mothers who do not breastfeed. To contain program costs, it uses a competitive bidding process under which infant formula manufacturers offer discounts, in the form of rebates, to state WIC programs in order to be selected as the sole formula provider to WIC participants in the state. This process yields $1.5 billion to $2 billion a year in rebates, with WIC paying on average only 8 percent of the formula’s wholesale cost.

As a result of these savings, while WIC provided an average value of $61.58 in food per participant per month in fiscal year 2014, the average monthly cost to the federal government was much lower: $43.42 per participant.

In addition, while food prices rose by 28 percent between fiscal years 2004 and 2014, WIC food costs grew by only 16 percent. Over the last five years, food prices rose by 10 percent, while WIC food costs rose by only 2 percent.

The portion of WIC funds devoted to nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and other services — a key part of the program’s success — has remained stable over time. Similarly, WIC’s administrative costs were 8 percent of total program costs in fiscal year 2013 and had been at that level or lower for more than a decade. By law, WIC funding per participant for nutrition services and administration combined may rise no faster than inflation. This constraint on administrative costs has limited federal expenditures but also can impede new initiatives, such as data system improvements, that require up-front investments in order to secure longer-term administrative savings.

Eligibility for WIC Benefits

Pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding women, infants, and children up to age 5 are eligible if they meet income guidelines and an appropriate professional has determined them to be at “nutritional risk.” Most applicants who meet the income requirements have a medical or dietary condition, such as anemia, that places them at nutritional risk.

All postpartum women who meet the income guidelines and nutritional risk criteria are eligible for WIC benefits for up to six months after childbirth; women who continue to breastfeed their infants beyond six months are eligible for WIC benefits for up to a year after childbirth.

Applicants who receive no other relevant means-tested benefits must have gross household income at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty level (currently $36,612 for a family of three) to qualify for WIC benefits. To simplify program administration, an applicant who already receives SNAP (formerly food stamps), Medicaid, or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families cash assistance is automatically considered income-eligible for WIC, even if the program’s income limit is above 185 percent of poverty. Roughly 75 percent of people approved for WIC benefits receive one of these other benefits.

Women may be referred to WIC by their doctor or when they apply for Medicaid or SNAP. They can apply for WIC benefits at one of WIC’s 9,000 local clinics, located in community health centers, schools, hospitals, and local health departments. Applicants must provide documentation confirming where they live, their identity, and their income or receipt of other qualifying benefits. Once approved, an individual usually receives WIC benefits for six months or a year, after which the participant must reapply. Errors can occur during this process if the applicant reports income or household size incorrectly or the WIC agency miscalculates income.

Purchasing WIC Foods

More than 48,000 grocery stores nationwide have been approved to accept WIC food vouchers based on their prices and the variety of foods they offer. Participants select their WIC foods from the shelves and use WIC vouchers to pay at the register. The state WIC program then reimburses the store for the retail value of the WIC foods. To ensure that WIC pays market prices, stores must charge the same price to all customers, regardless of whether they are participating in WIC.

Most states still use paper vouchers, but WIC is gradually transitioning to electronic benefit cards, which simplify WIC transactions in the checkout line, eliminate the stigma of paying with paper vouchers, and allow for stronger program management and oversight. Approximately one in four WIC participants receive electronic benefits; all states must make the switch by 2020. USDA anticipates that this change will increase efficiency and reduce inadvertent errors in the checkout line.

To be approved to accept WIC food vouchers, grocery stores must meet WIC food stocking and pricing requirements. WIC-approved vendors can be the source of program error and improper payments in various ways. To ensure compliance with program rules, managers, clerks, and cashiers at each of the thousands of WIC-approved vendors must be trained. And because there may be frequent staff turnover, such training must occur frequently.

Grocery Store Transactions

For WIC participants, especially the majority who still use paper food vouchers, choosing the correct WIC foods and going through the checkout line can be a daunting process. Within federal rules that determine the foods that can be offered to WIC participants, states are encouraged to adopt restrictions to contain costs. For example, a state might require participants to purchase a block of cheese rather than the same amount of shredded cheese or a gallon of milk rather than two half gallons. States may also require participants to choose a generic brand or the least expensive brand available.

These are important cost-saving mechanisms, but they make it harder for participants to choose the correct items and harder for vendors to ensure that program rules are followed. Local WIC staff train participants on these rules, but they can be hard to apply in the grocery store aisle. Once a participant goes through the checkout line, the cashier must make sure that each item is allowable and that the participant has a current voucher for that item. Participants report that when a mistake is identified, the process of correcting it can be so embarrassing and time consuming that they sometimes forgo the food item rather than trying to correct it.

Although a single voucher can only be used during a specified month, WIC clinics often issue more than one month’s worth of vouchers at a time to reduce multiple trips to the clinic or multiple mailings. Vouchers typically contain more than one food, but each participant may receive several vouchers each month, which together cover all of the prescribed WIC foods. So if a mother with an infant and a toddler is receiving WIC benefits, and each of them received five vouchers each month, the mother would receive 45 separate vouchers to be used over three months at a single appointment. When at the register, she must provide the correct vouchers to the cashier for the date she is shopping and the items she is purchasing.

Vendor Management

To ensure that the WIC program pays fair prices for foods, each state WIC program must implement a vendor management system with three main components: vendor peer groups, vendor pricing criteria, and maximum reimbursement rates.

When authorizing vendors, state WIC programs must ensure that all participants have reasonable access to a WIC-approved grocery store. WIC participants live in areas with widely divergent grocery stores and retail prices, and WIC-approved stores reflect this diversity. While the bulk of WIC-approved stores are large supermarkets, which tend to have the lowest retail prices, in some instances the WIC program authorizes smaller or more remote stores with higher retail prices to ensure participants have access to a store. Stores are categorized into “peer groups” based on factors such as size or geographic location, so that they can be compared to similar stores when considering pricing.

For each peer group, the state WIC program sets pricing criteria. To become a WIC-authorized vendor, each store must have retail prices that meet these pricing criteria. In addition, the state sets a maximum reimbursement amount for each voucher. These maximum reimbursement levels must take into account that even within a peer group or a single store, prices will vary somewhat over time and across similar items. But WIC does not reimburse stores for amounts in excess of the maximum reimbursement.

Electronic Benefits

Under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, state WIC agencies are required to transition to electronic benefit issuance by 2020. Most states have begun to develop the data systems necessary to make the transition, but currently only about one in four WIC participants receive electronic benefits. The one-time investment needed to develop and launch electronic benefits are difficult for states to funds with their regular WIC funding. Therefore, in recent years Congress has provided dedicated funding to improve management information systems, including the transition to electronic benefit systems.

Electronic benefits offer tremendous promise with regard to improving program integrity as well as simplifying the shopping experience for participants and store clerks. Electronic benefits can be programmed to prohibit the purchase of foods that are not allowable, without relying on cashiers’ understanding of WIC rules. They also allow state WIC programs to track reimbursements for each food separately, which is not possible with paper vouchers that cover several WIC foods. As a result, states can monitor reimbursements for patterns of high pricing or evidence of fraud. In addition, the information from electronic benefit systems can help states determine the best approach to peer grouping and setting pricing criteria and maximum reimbursement levels.

Assessing WIC Errors

USDA monitors and oversees WIC program accuracy. WIC errors have been thoroughly examined in two recent, nationally representative, studies: the 2012 National Survey of WIC Participants—II and the 2013 Vendor Management Study. These studies measure error rates and improper payments in two areas:

- Certification errors that result from household mistakes or mistakes by WIC staff, which are assessed by reviewing income documentation and conducting household interviews;

- Vendor errors that result from violations of program rules or errors when seeking reimbursement for WIC sales, which are assessed through “compliance buys” at WIC-approved stores.

In each category, USDA disaggregates overpayments and underpayments, which allows for a calculation of net costs and helps target interventions. These reports help make transparent the areas where errors occur and the ways in which federal and state program managers can improve accuracy.

WIC Program Integrity Measures

Since 1997, when Congress began providing enough WIC funding so that all eligible applicants can be served, USDA and Congress have taken steps to strengthen program integrity. While state WIC programs have discretion over specific vendor management practices, federal WIC rules require state agencies to authorize and manage their vendors to ensure the lowest practicable food prices while ensuring adequate access to WIC foods. About 1,900 local agencies in about 10,000 clinics around the country work hard on balancing these priorities, so it is important to ensure widespread understanding and consistent application of program rules regarding eligibility and allowable services and foods.

To strengthen efforts to reduce improper payments and ensure compliance with program rules, USDA in 2014 created a new WIC Program Integrity and Monitoring Branch. This is an important development that ensures USDA has a dedicated team of staff focused on strengthening oversight and supporting state efforts to ensure sound stewardship of federal funds. Additional efforts to address the main sources of program error are described in the remainder of this section.

Reducing Certification Errors

WIC eligibility rules have changed very little since the program’s inception. To ensure consistent application of those rules and provide additional direction in areas where there is state or local discretion, USDA issued updated guidance on income eligibility and documentation rules in April 2013. USDA then held a webinar in each region to train state staff on the guidance and address questions that emerged. State WIC staff are responsible for training local staff on the guidance.

To assess implementation of the new guidance and adherence to all eligibility rules, USDA will focus on eligibility determinations in its regular reviews, known as “management evaluations,” of state agencies over the course of fiscal years 2015 and 2016. These reviews are underway and will continue to be conducted over the next year and a half.

Strengthening Vendor Management

There are multiple kinds of vendor errors. For example, a vendor could allow participants to purchase foods or other items that are not part of WIC’s carefully tailored food package, either deliberately or because a cashier or participant does not understand WIC rules. A vendor could allow a participant to use an expired voucher. Or a vendor could seek reimbursement from the state for more foods than the participant actually received or for higher prices than the store actually charges.

State WIC programs are responsible for vendor oversight. As described above, states are required to establish criteria for approving WIC vendors based on business practices, pricing, and stocking practices. States also assign them to peer groups, ensure that their prices are consistent with local grocery prices, and set limits on the reimbursement WIC will provide for each voucher.

At various points in WIC’s history, WIC-approved vendors have found ways to violate, or exploit loopholes in, vendor rules. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was a rapid proliferation of “WIC-only” stores. These stores generally sold only WIC foods and only attempted to serve WIC participants. Because they made the shopping transaction much easier than at regular grocery stores and provided incentives to participants to shop there, they quickly attracted large segments of WIC participants in certain states. For example, in California, where these stores were most prevalent, 40 percent of WIC purchases in 2004 were made at WIC-only stores.

But WIC-only stores tended to have higher shelf prices than regular stores and as a result were driving up the cost of providing WIC benefits. WIC participants receive the same food items regardless of the shelf price charged for these foods. Participants consequently are not price-sensitive to the amounts that stores charge for WIC food items. Since regular retail food stores need to attract a wide customer base, market forces induce them to keep prices for WIC food items low enough to attract non-WIC shoppers; if a store prices these items too high, it is likely to lose customers to other stores. But WIC-only stores had no need to attract non-WIC customers — and thus no need to keep prices for WIC foods in line with the amounts charged at comparable stores that serve non-WIC customers. Therefore, WIC-only stores tended to have higher shelf prices than regular competitive stores.

The Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 strengthened vendor management rules for all stores and curbed the ability of WIC-only stores to drive up program costs. Since then, if a state chooses to authorize WIC-only stores, their peer group placement and pricing criteria must be designed to ensure that WIC-only stores are cost-neutral to the program. Moreover, WIC-only stores are not permitted to offer incentives of more than minimal value to entice WIC participants to shop there.

More recently, vendors in a few states found ways to violate program rules and exploit loopholes. For example, regular small grocery stores in California, which are not subject to the rules that apply to WIC-only stores, began applying for WIC authorization in increasing numbers and charging much higher prices for WIC-approved foods than other similar products. USDA’s regular management evaluation uncovered the problem and USDA worked closely with the state WIC program to establish an entirely new vendor management system, which quickly brought program costs back in line with competitive pricing. While the new system was being developed and implemented, USDA required the state to maintain a moratorium on authorizations of new vendors. USDA allowed the state to lift the moratorium only when the new system had been implemented, specific corrective actions had been taken, and the state program had sufficient vendor monitoring staff in place to ensure compliance with the new vendor rules.

In response to similar troubling findings in management evaluations in a couple of other states, USDA decided to focus management evaluations during fiscal years 2013 and 2014 on vendor management. USDA is now using those findings to identify areas where states could benefit from additional support and where stronger oversight is needed. In addition, USDA has identified specific follow-up activities that state WIC programs must take to address deficiencies.

Up until now, states have designed their vendor management rules and targeted oversight efforts without the benefit of a systematic review of best practices. To provide states with more guidance and information, USDA has launched two studies focused on vendor management. One study is closely examining peer grouping in six states to assess the effectiveness of the peer group criteria in use and hypothetical alternatives. This study will also identify best practices and innovative approaches to peer grouping. The other study focuses on how states can best identify high-risk vendors so they can target oversight and compliance resources most effectively.

Future WIC Program Integrity Improvements

The reauthorization process offers an opportunity to identify and support strategies to reduce errors in the WIC program. We recommend that the Committee consider the following ideas for further exploration. Some of these ideas do not require authorizing language but would require sufficient appropriations to support the new or expanded activity.

- Certification guidance. The findings of USDA’s management reviews focused on eligibility determinations will offer a rich supply of information to help target additional efforts to improve the accuracy of eligibility determinations. Once USDA has conducted the reviews, the department can assess the findings to identify areas where more guidance or oversight would be helpful. USDA can then develop guidance and conduct trainings focused on these areas.

- Electronic benefits. In certain recent years, Congress has provided dedicated funding for management information system improvements, including the transition to electronic benefit issuance. Continued funding for these improvements is essential to reducing errors in the WIC program and enabling state WIC programs to strengthen program management and compliance on a long-term basis. It will also make it substantially easier for participants to obtain WIC foods, enhancing WIC’s effectiveness. Providing the full amount of funding needed to allow states to transition to electronic benefits without the uncertainty of the annual appropriations process would allow USDA and states to plan their transitions and would help ensure that all states are offering electronic benefits by the 2020 deadline in federal law.

- Management evaluations. Since fiscal year 2013, USDA has focused its regular reviews of state WIC programs, known as management evaluations, on the two primary areas of program error: certification error and vendor error. These evaluations have identified specific weakness that states are then required to address. Another important use of the information gathered in these evaluations is to identify patterns across states so that USDA can provide support where it is most needed and share best practices. USDA has begun the process of gathering this kind of information, but it is worth exploring whether this Committee can further that process.

- Implement vendor study findings. The two studies that are underway — focused on identifying vendor peer grouping best practices and identifying high-risk vendors — will yield important information that states can use to restructure and strengthen their vendor management rules and oversight efforts. But the release of the reports is only the first step. It will be important to develop channels for disseminating the results and helping states implement them.

- Identify and disseminate cost-containment best practices. USDA encourages states to adopt policies that contain the costs of the foods WIC provides. But it has been more than a decade since a systematic assessment of the effectiveness of these policies was conducted. USDA has launched new research to identify best practices with regard to food package cost containment, such as policies related to the brand and form of WIC foods participants may purchase. One study will update a 2003 analysis of the effectiveness of specific cost-containment practices. In addition, the Duke-UNC-USDA Center for Behavioral Economics and Healthy Food Choice Research is offering research grants focused on WIC food cost-containment. As in the arena of vendor management, the findings from these research grants can inform the policy decisions that states regularly make. Developing a plan for trainings or peer-to-peer sharing that will allow states to apply these and other research findings will help ensure that investments in research yield real world results.

Conclusion

The school meals and WIC programs help shield children from hunger, are important investments in children’s health and development, and prepare them to learn and thrive. The school meals and WIC programs help shield children from hunger. To keep these programs strong, it is important to make sure that program rules are sensible and followed. USDA’s nationally representative studies of the school meal programs and WIC show that there is room for improvement in program accuracy and integrity. The APEC report, in particular, includes a wealth of information that can be used to develop measures to improve program integrity by building on the efforts of the many school districts and states that have already achieved high accuracy. USDA’s recent oversight actions on WIC provide a strong framework for identifying and addressing current concerns and targeting future program integrity measures.

When developing program integrity proposals, we urge Congress and USDA to carefully tailor interventions to specific problems and assess whether a proposed measure meets key criteria:

- Will it have a demonstrated impact on reducing error?

- Will it maintain program access for the most vulnerable children?

- Is it feasible?

- Is it cost-effective?

Proposals that meet these criteria can be pursued without exacerbating food insecurity for low-income children or overly burdening schools. Proposals that focus on expanded use of data from other programs and sources are especially promising, as are measures that take advantage of more widespread use of technology by school systems in recent years. To ensure that low-income children receive the benefits for which they qualify, it is important to address errors that result in underpayments as well as overpayments.

More from the Authors