BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Most states’ prison populations are at historic highs, I explained yesterday, imposing high costs on states even as many states have cut education funding. Here’s a closer look at the causes and impacts of high incarceration rates:

Incarceration rates have risen mainly because states are sending a much larger share of offenders to prison and keeping them there longer — two factors under policymakers’ direct control. Reforms to reduce prison populations will need to target these two areas.

More specifically, research on the causes of rising incarceration rates has found:

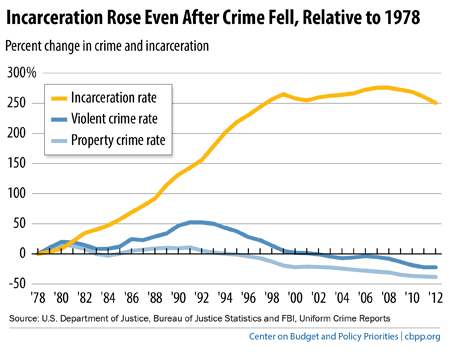

- Crime rates have risen and fallen independently of incarceration rates. Crime rates began rising in the early 1960s, roughly a decade before incarceration rates did. In the 1980s, violent and property crime rates fluctuated, while incarceration rates continued rising. By the end of the 1990s, crime rates had fallen to 1970s levels, and they have continued to fall throughout the 2000s; yet incarceration rates continued to grow well into the 2000s, peaking in 2007 (see graph).

- Arrests per crime have been relatively stable. Incarceration rates may rise even when crime rates remain stable if police become more effective at apprehending offenders. Yet, “by the measure of the ratio of arrests to crimes, no increase in policing effectiveness occurred from 1980 to 2010 that might explain higher rates of incarceration,” a recent National Research Council report concluded.

- The share of offenders sent to prison has climbed dramatically. For all major crime types, the likelihood that a person convicted of a crime will go to prison has risen sharply over the past 30 years. That’s especially true for drug offenses; the likelihood of being sent to prison for a drug-related crime rose by 350 percent between 1980 and 2010. The increase in the share of offenders sent to prison accounts for 44 to 49 percent of the long-term growth in state incarceration rates, the National Research Council study estimated.

- Length of stay in prison has grown for all types of crimes. Between 1990 and 2009, the average time served rose by nearly 25 percent for property crimes and by roughly 37 percent for violent and drug crimes, the Pew Center on the States estimates. The increase in average sentences has contributed as much to the growth in incarceration rates as the rise in the share of offenders sent to prison, and possibly slightly more.

High incarceration rates impose significant human (as well as budgetary) costs. People with criminal convictions face serious challenges in finding stable, decent-paying jobs. Time behind bars is generally time lost developing the skills and education increasingly necessary in today’s labor market, a particular problem given that formerly incarcerated people typically have less education.

Even those who do find jobs typically earn less than otherwise-similar people who haven’t been incarcerated. A Pew study found that men with a criminal conviction worked roughly nine fewer weeks, and earned 40 percent less, each year than otherwise similar non-offenders.

Incarceration also increases poverty, for former inmates as well as other household members, including children. Many inmates are also parents and/or partners, and their incarceration leaves households with one less potential wage earner.

Tomorrow I’ll outline some ways that states can reduce high incarceration rates, generating savings that they can use more productively.