BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Taking Stock of the Safety Net, Part 5: Helping Families Stay Afloat During Unemployment Spells

Unemployment Insurance (UI) replaces up to half of the income that workers lose when they become unemployed through no fault of their own. That lessens the financial strain on their families while these workers look for new jobs. In a weak economy like the current one, UI also helps sustain consumer demand, keeping a downturn from being worse and providing a boost for a recovery.

As in previous recessions, policymakers responded to the deep recession that began in December 2007 by giving additional weeks of federally funded UI benefits to workers who run out of regular, state-funded UI benefits before they can find a job.

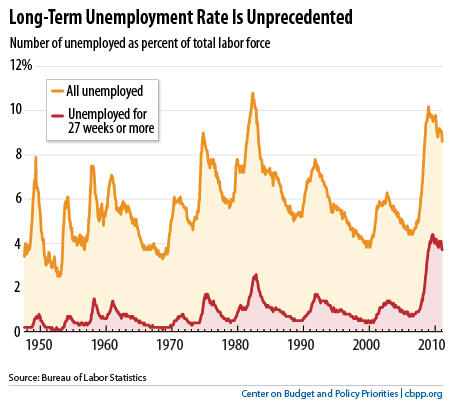

The number of people receiving UI benefits in a given week quadrupled from about 3 million at the start of the recession to a peak of 12 million in early 2010, according to Labor Department data. Although that number has since dropped below 7 million, jobs remain hard to find and the long-term unemployment rate is unprecedentedly high (see chart). Two-fifths of the unemployed have been looking for work for more than 26 weeks, the most weeks that state UI programs typically provide.

UI has done its job well thus far, such as by keeping 4.6 million people out of poverty in 2010 — 3.2 million of them as a result of the federal emergency UI benefits. But the prolonged economic slump has placed considerable strain on the UI system:

- Federal benefits in danger. Congress has never let emergency federal UI expire when the unemployment rate has been as high as it is now, yet the fate of federal UI benefits in 2012 remains in legislative limbo. If Congress doesn’t act before the end of this year, almost 2 million workers face a loss of benefits in January.

- State benefit reductions. Arkansas, Missouri, and South Carolina reduced the maximum number of weeks of UI benefits in 2011, and three more states — Florida, Illinois, and Michigan — will reduce benefits in January 2012.

- “Reform” proposals that weaken the system. UI has always been a social insurance program that helps workers who have lost their job through no fault of their own. Proposals like those in the recent House UI bill, which would require drug tests for UI recipients, deny benefits to all workers who lack a high school diploma or GED certificate and are not enrolled in classes to get one, and allow states to use UI funds for purposes other than paying benefits, would alter the very nature of the program and make it harder to qualify for benefits. They also would make the system more costly to administer.

- Unaddressed solvency issues. A number of states’ UI trust funds were inadequately prepared for the recession because states had kept the employer tax that pays for UI benefits artificially low. Most states have borrowed from the federal government in the past few years to help pay benefits, and that debt is creating significant pressure in state legislatures to cut UI benefits.

Moreover, without reform, most state UI trust funds likely will face the next recession either still in debt from the current downturn or so weak that they will quickly be back in debt. A bill introduced in the Senate earlier this year, building on a proposal by President Obama, would give states a framework to restore the health of their trust funds. Unfortunately, Congress hasn’t acted on it — or any other proposal to improve UI financing for the future.