BEYOND THE NUMBERS

U.S.-based multinational corporations that are lobbying Congress to adopt a “territorial” tax system, which would cut their taxes on foreign profits to zero or a very low rate, often note that many other developed countries have such systems. But those countries are a warning, not a model, as a great new analysis by former Joint Tax Committee Chief of Staff (and now University of Southern California Law School Professor) Edward Kleinbard shows.

The United Kingdom has a territorial system, so it generally only taxes profits that a corporation earns in the UK. UK policymakers and citizens have been outraged to learn that Starbucks UK, despite capturing nearly a third of the UK coffee market in 2011, paid no corporate tax in 2011 (or in 12 of the 13 years before that).

How did Starbucks UK do it? By claiming big losses instead of big (taxable) profits.

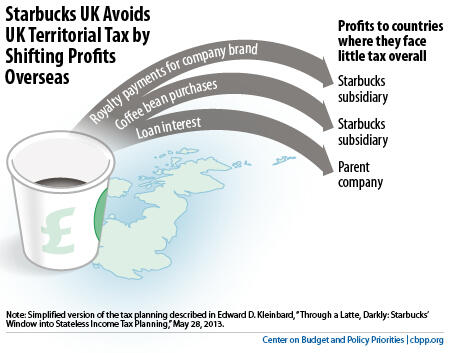

As Kleinbard shows, Starbucks UK apparently used three classic accounting techniques to shift profits to countries where it faces very little tax overall, such as to Starbucks subsidiaries in low-tax and tax-haven countries. In each case, Starbucks UK imposed more costs on itself (thus lowering its profits in the UK) while, at the same time, boosting its profits in lower-tax countries overall.

- Royalties. Starbucks UK paid Starbucks companies in other countries (such as the Netherlands) huge royalties for the right to use the Starbucks brand, store design, and other intellectual property. As Kleinbard points out, Starbucks is generally viewed as a traditional retail business that sells tangible goods and services; if it can shift large profits offshore through royalty payments for intellectual property, then any company can do it.

- “Transfer pricing.” Starbucks UK paid what appear to be inflated prices on coffee beans to Starbucks-owned bean companies in low-tax countries.

- Interest payments. Starbucks UK took a big loan from its U.S. parent company and paid large amounts of interest on it. (As Kleinbard details in the paper, however, this doesn’t mean that Starbucks paid significant U.S. tax on that interest.)

Where did all these profits ultimately go? Some of the royalty payments and coffee bean sales income came to rest in a Starbucks subsidiary in the Netherlands where, Kleinbard says, they faced a virtually zero tax rate. But given Starbucks’ web of subsidiaries across the globe, and the fact that it doesn’t have to report all of its tax arrangements to any one country or its shareholders, it’s impossible to know where all the profits ended up. In fact, Kleinbard points out, some of Starbucks’ profits may have ended up “stateless” – that is, not taxed anywhere.

If the United States adopted a territorial tax system, multinationals would have a similar incentive to move U.S.-earned profits to tax havens and low-tax countries rather than report them – and pay tax on them – in the United States. The Starbucks example shows just how easy that is.