BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Due to the proposal in the House Republican health bill to convert Medicaid to a per capita cap or block grant, the aging of baby boomers would likely exacerbate the federal Medicaid spending cuts over the long run.

The Congressional Budget Office already estimates that the version of the legislation that the House Budget Committee approved recently would cut federal Medicaid spending by $839 billion over ten years, and Medicaid enrollment by 14 million, by 2026. But the spending cuts could likely grow faster after the first decade because the per capita or block grant amounts in the legislation won’t account for the considerably higher health and long-term care costs that will result from a growing share of the baby boomers moving from “young-old age” to “old-old age,” — i.e., age 85 or older.

Starting in 2020, the House plan would limit federal Medicaid funding to states either on a per beneficiary basis (per capita cap), or on an overall program basis (block grant) — whichever a state chooses. Under either scenario, the plan uses states’ Medicaid per beneficiary spending in 2016 to set a federal funding limit that grows each year more slowly than current spending projections.

Average health care spending per beneficiary, however, is very different for the four standard populations enrolled in Medicaid — seniors, people with disabilities, children, and other adults. Seniors’ average health care spending is about five times that of children and other non-disabled adults. The House plan proposes to account for this difference by setting separate per beneficiary federal funding caps for seniors and other beneficiary groups, which it then uses to determine the per capita cap or block grant amounts starting in 2020.

Neither the per capita cap nor the block grant accounts for expected changes within Medicaid beneficiary groups, such as among seniors. As noted, the per capita cap and block grants are based on what states spent in 2016. So this locks in the beneficiary mix within that group at the time, including the age distribution of seniors.

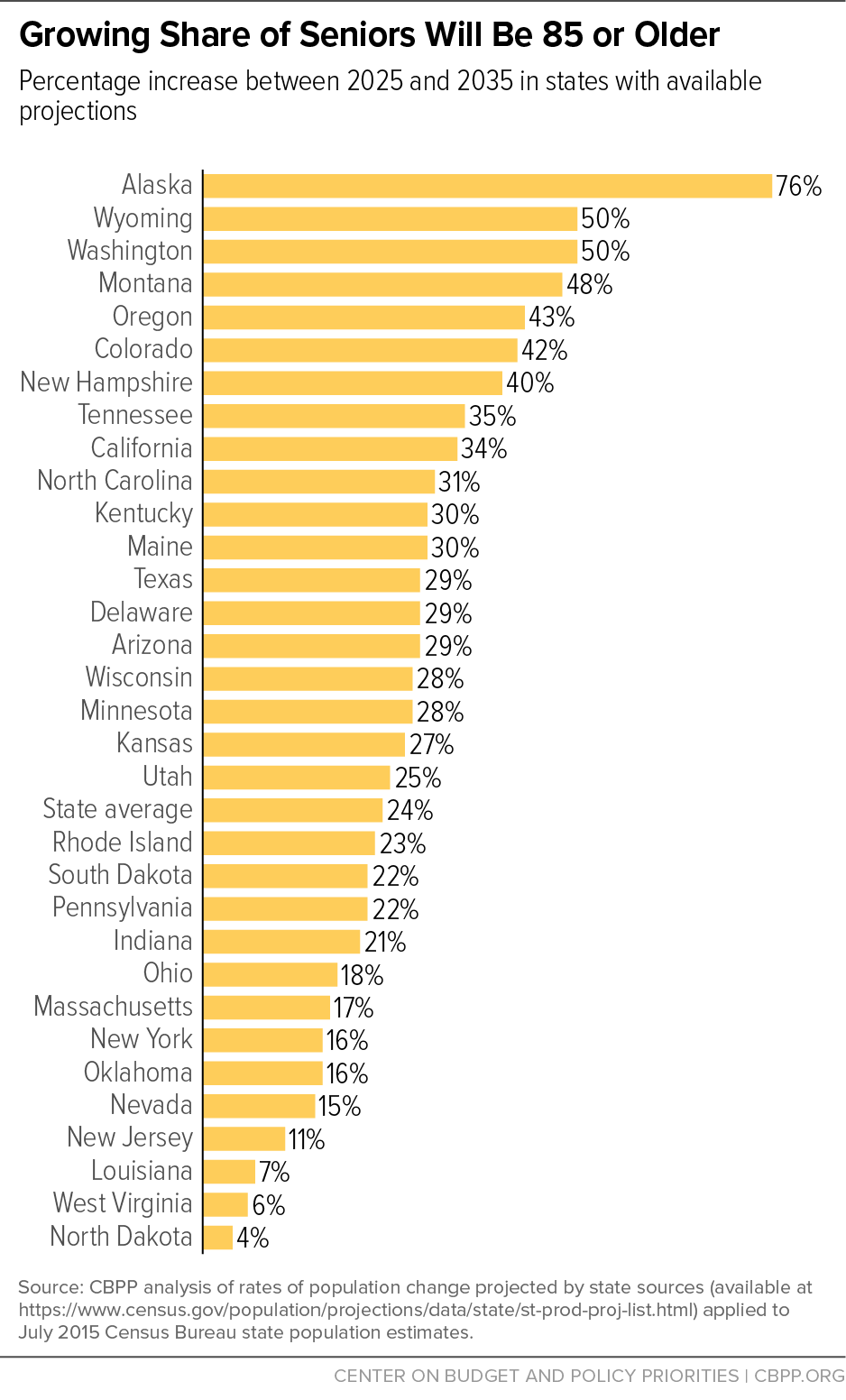

But over time, a growing share of seniors, including those on Medicaid, will be 85 or older. For example, all 32 states with available projections estimate that the share of their seniors who are 85 and older will rise between 2025 and 2035, and well more than half of these states project an increase of at least 25 percent. Alaska will see a 76 percent increase between 2025 and 2035. (See graph.)

People in their 80s or 90s have more serious and chronic health problems and are likelier to require nursing home and other long-term care than younger seniors. For example, seniors aged 85 and older incurred average Medicaid costs in 2011 that were more than 2.5 times higher than those aged 65 to 74, based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. A per capita cap or a block grant would thus cut state Medicaid programs by increasingly deep amounts over the long run as more boomers move into “old-old age,” just as the explicit cuts under the per capita or block grant exceed 25 percent, relative to current law.

This is yet another reason why the House bill’s proposal to convert Medicaid to a per capita cap or block grant would prove so damaging. It would shift more and more costs to states and, to compensate, states would have to make increasingly draconian cuts to their Medicaid programs, driving many millions into the ranks of the uninsured or reducing access to needed care. These problems would be exacerbated when the population’s aging puts even more severe fiscal pressures on states to shrink their programs. Millions of seniors as well as children and families, people with disabilities, and other adults who rely on Medicaid today would pay the price.