BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Critics continue to offer potentially misleading claims about the Disability Insurance (DI) program — a vital part of Social Security that pays modest benefits to people who can no longer do substantial work due to a severe medical impairment — and a recent Washington Post editorial gave some of them wider attention.

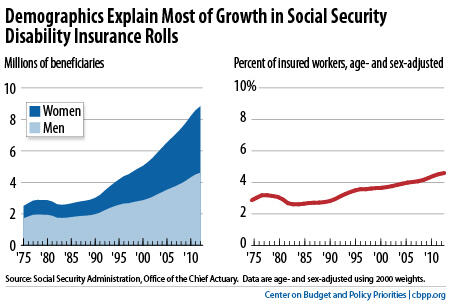

The critics whom the Post cites give short shrift to the role of demographic factors in growing the DI rolls. As we’ve noted, three big demographic factors — the aging of the baby boomers into their 50s and 60s (the peak ages for DI receipt), the rise in women’s labor force participation (which means more women now qualify for DI benefits), and the rise in Social Security’s full retirement age (which delays DI beneficiaries’ reclassification as retired workers) explain most of the growth.

While the number of disabled workers tripled between 1980 and 2012, the Social Security Administration’s (SSA) actuaries show that — when properly adjusted for age and sex — they represented 3.1 percent of the insured population (people who have worked long enough to qualify for DI in the event of a severe medical impairment) in 1980 and they represent 4.6 percent today. (See graph.) That’s not “explosive growth,” as the Post claims. Several of the academic researchers in question express DI receipt as a share of the entire population aged 20 to 64, a different measure that — especially over certain time periods — tends to downplay the impacts of demographic change. In particular, a recent study by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, which the Post cites, may leave the mistaken impression that 44 percent of today’s cases can’t be explained. That would mark a misreading of the study (as we’ll examine in a forthcoming paper).

The critics also suggest that eligibility standards are lax. In fact, most applications are denied. That’s especially true in economic downturns, when applications soar. The agency requires convincing medical evidence from qualified sources. The disability criteria are so strict that most beneficiaries — despite significant work incentives — do not work to supplement their modest benefits, and even rejected applicants struggle in the labor market. And SSA regularly reviews beneficiaries to weed out those who have recovered, though Congress has stymied this effort by starving the watchdogs.

While some benefit and eligibility rules merit review, the program does its job pretty well. It pays modest, but vital, benefits to severely impaired workers, mostly in their 50s and 60s with limited education and high mortality rates. Policymakers should therefore approach reform with caution, as an earlier Post editorial argued convincingly. For example, proposals to turn DI into a block grant or require employers to pay more of the cost raise serious concerns about the resulting erosion of benefits and possible discrimination in hiring and retention. And as a practical matter, such ideas should be carefully tested and analyzed in small-scale pilots. That’s not feasible before the separate DI fund needs to be replenished in 2016, a date that comes as no surprise and poses no crisis.

As eight former Commissioners of Social Security from both parties recently wrote, “With the lives of so many vulnerable people at stake, it is vital that future reporting on the DI and SSI programs look at all parts of this important issue and take a balanced, careful look at how to preserve and strengthen these vital parts of our nation’s Social Security system.” We agree.