BEYOND THE NUMBERS

As Congress debates whether to extend expired federal unemployment insurance (UI) benefits, the issue of offsetting its costs has become a flash point. At the same time, members of both parties are pushing to extend several dozen tax breaks that expired at year-end (mostly for corporations), with little concern about whether they are paid for. That’s backwards.

The emergency UI program is truly temporary; similar past programs have all ended once the labor market improved significantly. The program has little impact on the long-term budget outlook if it isn’t paid for. In contrast, the so-called “tax extenders” are truly perennial because Congress routinely extends them year after year, and they consequently have a vastly greater impact on our long-term budget problems if their cost is not offset.

Policymakers should commit to offsetting the cost of tax extenders. And the need to pay for continuing those extenders that withstand scrutiny should provide an opportunity to pare inefficient tax subsidies, with which the tax code is replete.

Temporary programs like the Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) program, which policymakers have established in every major recession since the 1950s, do two things. First, the relatively modest weekly checks they provide reduce real hardship for people who want to work but can’t find jobs in a weak labor market. Second, these checks help prop up overall consumer demand, thereby encouraging economic growth and job creation.

EUC is a textbook example of a temporary “counter-cyclical” program that helps cushion the impact of economic downturns, and continuing EUC for one more year poses negligible long-term risk to the budget. Moreover, when more than 1 million Americans lost emergency UI benefits over the holidays as EUC expired, it became harder for many of them to heat their homes, feed their families, and make car and other monthly payments.

Policymakers have nonetheless expressed concern about the fiscal effect of extending EUC, arguing that these emergency benefits must be paid for. A statement from Senator Kelly Ayotte’s (R-NH) office, for example, states that she has “concerns that the proposal is not paid for and would add $6.4 billion to the national debt over the next 10 years.”

Senator Ayotte’s concern is worth keeping in mind when one considers that continuing all of the tax extenders — those that just expired plus those scheduled to expire in later years — would cost about $50 billion a year. And, their supporters view these tax breaks as anything but temporary. Once an extender is enacted, its supporters push — usually successfully — to extend it year after year.

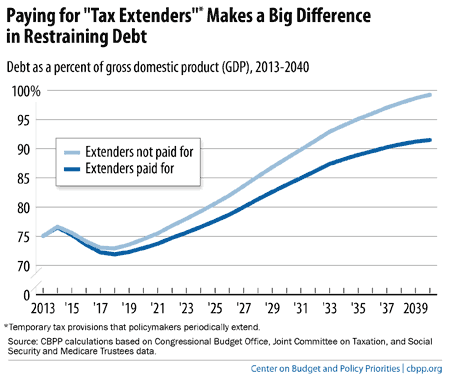

If extended without offsets, whether permanently or one year at a time, these provisions would cost roughly $500 billion over the next decade. That’s real money that adds significantly to the debt, as the chart makes clear:

In last month’s budget deal, policymakers required that the cost of replacing sequestration cuts in 2014 and 2015 be fully offset. As noted, they’re now searching for offsets to extend emergency UI benefits. And they also plan to offset the cost of continuing relief for physicians from scheduled deep cuts in Medicare reimbursement rates.

Policymakers should similarly focus on offsetting the cost of the tax extenders. If they are truly concerned about the debt, as they claim, then there is no excuse for offsetting the costs of sequestration relief, a UI extension, and relief for Medicare physicians but not offsetting the cost of continuing this grab-bag of tax breaks. The Administration and Congress should insist that policymakers fully pay for the extenders from now on. That step alone would erase as much as one-third of the expected climb in the debt as a share of the economy between now and 2040.