Thank you for the opportunity to testify. I am Peggy Bailey, Vice President for Housing Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The Center is an independent, nonprofit policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income families. The Center’s housing work focuses on increasing access and improving the effectiveness of federal low-income rental assistance programs.

Seventy-five percent of households eligible for federal rental assistance do not receive it due to limited funding.[1] Families may wait for years to receive housing assistance, and overwhelming demand has prompted most housing agencies to stop taking applications entirely.[2] According to the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, this contributes to over 47 percent (20.5 million) of renter households spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs, and almost 25 percent (11 million) spending more than 50 percent of their income on housing.[3]

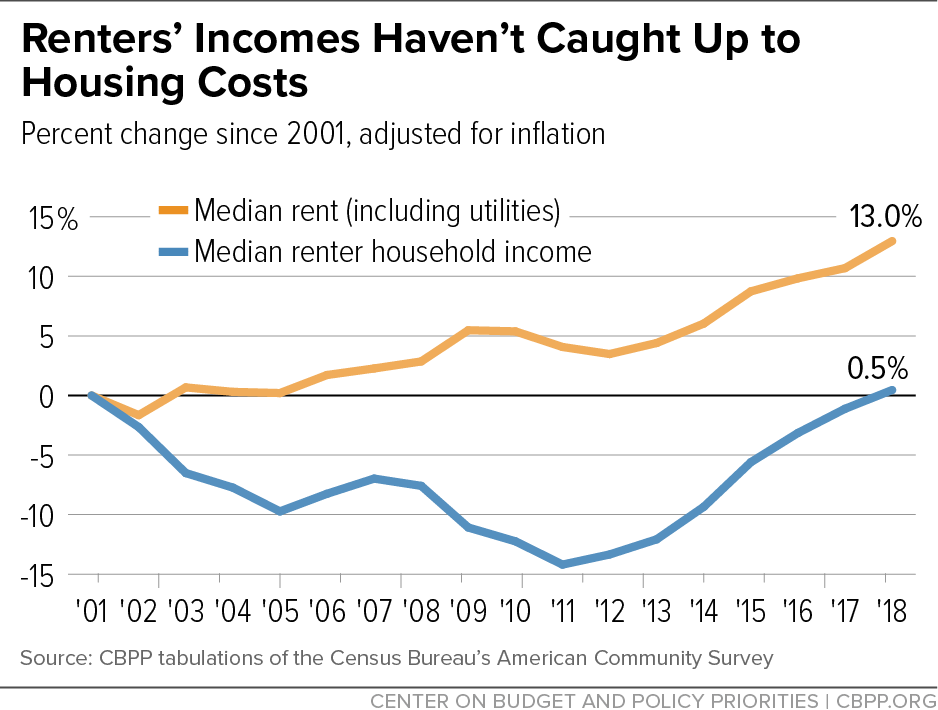

The gap between housing costs and people’s incomes isn’t getting better. Recent Census data show that, after adjusting for inflation, between 2001 and 2018 rent costs including utilities grew by 13 percent but incomes rose only .5 percent. (See Figure 1.)

When people struggle to pay the rent, they not only face financial and housing instability, but they are also at heightened risk for a host of negative health outcomes. More generally, high housing costs worsen the adversity that people with low incomes experience, forcing them to face a persistent threat of eviction and make difficult choices between paying the rent and paying for medicine, food, heating, transportation, and other essentials. High costs may also compel people to live in housing or neighborhoods that are rife with health and safety risks. These consequences can contribute to “toxic stress” and other mental health conditions that alone can be devastating but can also exacerbate physical health conditions for adults and children.[4]

Youth leaving the foster care system are a particularly vulnerable group and are disproportionately at-risk of homelessness and housing instability. These young adults often have limited or no family financial or emotional support, they can struggle to continue their educations or succeed in jobs, and if employed, often are paid low wages. They are navigating the adult world at a young age, with few of the resources — both financial and the support of caring, mature adults — that middle- and high-income young adults often rely on.

Federal and state policymakers have an obligation to do more to help these young people, who have been the responsibility of both federal and state government during formative years, to transition successfully to independence. This testimony focuses on what can be done to help more young people who have exited foster care to find decent, stable, affordable places to live, which is so important to protecting them from further hardship and trauma and helping them to transition successfully to adulthood.

Specifically, it’s essential that Congress:

- Advance HR 4300 Fostering Stable Housing Opportunities Act of 2019, which:

- Expands foster youths’ access to Housing Choice Vouchers by streamlining the administration of the Family Unification Program (FUP).

- Incentivizes housing agencies by allowing HUD to distribute additional administrative support to agencies that serve these young people.

- Allows housing agencies to lengthen the duration of assistance for foster youth who are working, in school, receiving training, engaged in substance use treatment services, are parents of young children, or have documented medical conditions that limits their ability to work or attend school.

- Accept the proposed funding increases in the FUP targeted to at-risk foster youth that are currently included in both the House and Senate fiscal year 2020 appropriations bills.

- Protect youth from discrimination and ensure access to housing and social service supports.

Of the approximately 400,000 children in foster care, some 20,000 young people age out of foster care each year; in some states this happens at age 18 while other states extend foster care modestly to ages 19 to 21.[5],[6] Foster youth enter adulthood facing challenges that place them at a severe disadvantage relative to other young people. While large shares of other young adults live at home with their parents — or attend a residential college or university — and receive substantial financial and emotional support from their parents, foster youth typically have few financial resources and receive little or no family support. In addition, many enter adulthood with histories of trauma, incomplete educational preparation, and poor job skills.[7]

Based on their representation in the United States as a whole compared to their representation in the foster care system, a disproportionate share of youth exiting foster care are Black or Hispanic and may face racism and discrimination when seeking housing, jobs, and educational supports.[8] Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning (LGBTQ) young people are also over-represented in the foster care system and face unique challenges — such as job discrimination and trauma that can stem from not being accepted by their families and communities of origin — as they transition to adulthood that can be more difficult if they are uncertain how they will afford a place to live or take care of other basic needs. Young people who exit foster care strive to make progress — about three-quarters are either enrolled in an educational program or working at age 21 — but their experience in foster care, lack of financial resources, and the lack of support from caring, mature adults can make it difficult to transition successfully to independence.[9]

Deepening the challenges, many of these young people struggle to find a stable place to live. About 1 in 4 former foster youth who are 21 years old report having been homeless at least once during the prior two years, while other surveys find that as many as 1 in 3 experience homelessness by age 26.[10] Not surprisingly, foster youth make up a large share of the broader population of youth who are homeless — as many as one-half according to one survey.[11] Surveys also indicate that, of the foster youth who experience homelessness, more than half experience homelessness repeatedly or for extended periods.[12] Often, the experience of homelessness extends well into adulthood.

Homelessness and other types of housing insecurity make it very hard for young adults to succeed in school or work. While few studies focus on homelessness’ effects on the educational achievement of foster youth, there’s reason for concern. Numerous studies find that homelessness undermines children’s school achievement generally, and studies find that a larger-than-average share of foster youth are already not making adequate progress in school at the time of their emancipation. At age 19, for example, nearly half of foster youth have not completed high school, and nearly one-third still have not by age 21.[13]

Homelessness also increases foster youths’ risk of rape and assault, substance use, depression, and suicide.[14] A survey of homeless youth in 11 cities found, for example, that 15 percent had been raped or sexually assaulted, 28 percent had agreed to have sex in exchange for a place to spend the night, and 32 percent had been beaten. Almost two-thirds reported symptoms of depression, and more than one-third reported using hard drugs.[15]

Expanding Foster Youths’ Access to Housing Vouchers Is Part of the Solution

Federal and state agencies have a special responsibility to help former foster youth transition successfully to adulthood. State agencies — with some funding and oversight from the federal government — have legal custody of children in foster care and are responsible for ensuring they receive adequate care. These agencies in effect stand in for parents unable to care for their children. But most American parents continue to help their children in various ways after they turn 18 (or even 21).

In light of foster youths’ extreme vulnerability and the special responsibility that federal and state agencies have for them, Congress should do more to help them transition successfully to independence. Child welfare agencies clearly have an important role to play, and policymakers have approved several major pieces of legislation in recent years aimed at encouraging and equipping child welfare agencies to expand services and support for young people up to age 21, and even beyond in some cases.[16] But federal, state, and local housing agencies also have important roles to play, and Congress should look for opportunities to strengthen their roles, in part by strengthening the housing assistance programs they administer, as well as to improve the coordination of housing and child welfare agencies in supporting former foster youth.

One important tool is the federal Housing Choice Voucher program. Created in the 1970s, the housing voucher program helps low-income people pay for housing they find in the private market. A network of 2,200 state and local housing agencies administer the program. More than 5 million people in 2.2 million low-income households use housing vouchers. Nearly all of these households contain children, seniors, or people with disabilities.

Rigorous research consistently finds that housing vouchers sharply reduce homelessness, housing instability, overcrowding, and other hardships.[17] Indeed, housing vouchers have played a central role in policymakers’ successful efforts to reduce veterans’ homelessness, which has declined by nearly 50 percent since 2010, evidence that well-resourced, targeted programs can move the needle on a difficult problem.

Housing vouchers are also cost-effective and flexible. For instance, because they are portable, families may use them to move to safer neighborhoods with quality schools and other opportunities that can improve their health and well-being, as well as their children’s chances of long-term success. (Many young adults who have left foster youth are young parents, making this evidence relevant for this population.) Housing agencies may also “project-base” a share of their vouchers — that is, link the housing voucher to a particular housing development where, for example, residents may have access to services that help them to remain stably housed and improve their well-being. Project-based vouchers are used successfully in supportive housing, for example, which connects affordable housing with mental health and other services that support people and help them remain stably housed, and has been used successfully to reduce homelessness among people who have lived on the street or in shelters for long periods, including youth exiting the foster care system.[18] Project-based vouchers may offer opportunities for housing agencies to partner with child welfare agencies and community partners to link housing and other forms of support for former foster youth learning to navigate the adult world.

Young people who have left foster care are eligible for Housing Choice Vouchers. But, as stated above, there’s a severe shortage of housing vouchers overall: only 1 in 4 eligible households receives a voucher or other federal rental assistance due to limited funding, and applicants typically wait years to receive aid. Under authority provided by Congress and the President, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) makes a small pool of vouchers (Family Unification Program or FUP vouchers) available to state and local housing agencies that partner with child welfare agencies to help at-risk youth and families. But there are only 20,000 FUP vouchers in use total and only a small share of the vouchers go to former foster youth.

- The geographic reach of FUP vouchers is limited. Only some 280 agencies — or roughly 1 out every 8 of the more than 2,200 housing agencies nationwide — are even authorized to administer FUP vouchers.[19] Because the vast majority of housing agencies administer vouchers within a limited geographic area (state housing agencies are a major exception), this limits youth and families’ access to FUP vouchers based on geography, in addition to the overall shortage of the vouchers.

- Most FUP vouchers go to families, not former foster youth. Of the nearly 20,000 FUP vouchers that are currently in use, less than 1,000 are being used by former foster youth, according to HUD.[20] Most FUP vouchers, understandably, go to families to help prevent the need for a child to be removed and placed in foster care or to families that, with a voucher, will be able to reunite with children placed in foster care.

Streamlining and Strengthening FUP Vouchers for Foster Youth

The Fostering Stable Housing Opportunities Act of 2019 (HR 4300), sponsored by Representatives Madeleine Dean (D-PA), Mike Turner (R-OH), Karen Bass (D-CA), and Steve Stivers (R-OH), would institute several important changes to improve the efficacy of FUP vouchers for foster youth. Specifically, the bill, which the House Financial Services Committee recently reported out on a unanimous, bipartisan vote, would:

- Streamline the FUP voucher allocation process to enable many more housing agencies to make them available to eligible foster youth. Historically, HUD has been required to allocate FUP vouchers to housing agencies through a cumbersome, time-consuming competitive process that has limited the number of housing agencies that administer FUP vouchers. This, combined with inadequate funding, means that some foster youth have no chance of receiving a voucher; if funding is increased, additional agencies could become eligible to administer FUP vouchers, but the benefits would remain concentrated in too few geographic areas. The Fostering Stable Housing Opportunities Act would authorize HUD to make FUP vouchers available to every housing agency that currently administers vouchers and would like to administer FUP vouchers, so long as the agency meets program requirements (and subject to the availability of funds). The goal of this more streamlined process is to enable housing agencies to receive a voucher from HUD when a child welfare agency requests one on behalf of an at-risk young person. This “on-demand” process — particularly if paired with additional vouchers, as proposed by both the House and Senate appropriations bills — would better meet the needs of at-risk foster youth, particularly in communities where FUP vouchers are not currently available.

- Support foster youths’ participation in educational, training, and work activities. The Fostering Stable Housing Opportunities Act also encourages housing agencies and child welfare agencies to connect youth to supports that can help them become independent. It also would allow youth to use their FUP vouchers for up to 60 months (i.e., 24 months beyond the current limit of 36 months) if they are enrolled in educational or training programs, or are working. Supporting youth for an extended period can be critical to helping them complete educational or training programs and provide an incentive for them to engage in activities that help them advance towards independence.

- Provide supplemental funding for housing agencies to support their partnerships with child welfare agencies and connect youth to services and other resources in the community.

It is important to note that 71 organizations representing foster youth from across the country — spearheaded by Foster Action Ohio, an organization that is led by foster care alumni and supported by the National Center for Housing and Child Welfare — not only support the Fostering Stable Housing Opportunities Act but have played a central role in designing and drafting the bill.[21]

These important policy changes must be accompanied by additional funding for FUP vouchers in order to expand the availability of rental assistance for former foster youth and enable more of them to avoid homelessness during their transition. Fortunately, there are opportunities on this front, as well. Both the House and Senate versions of the Transportation-HUD appropriations bill for fiscal year 2020 include $20 million to expand the availability of FUP vouchers for at-risk foster youth. This funding would enable more than 2,000 young people who have exited foster care and are at-risk of homelessness to live in decent, stable housing. The House bill also includes an additional $20 million for FUP vouchers (i.e., $40 million in total for FUP, some of which would be used to provide housing vouchers to at-risk families). Congress should make it a priority to include these funds — including the additional funding for new FUP vouchers for at-risk families in the House bill — in the final fiscal year 2020 appropriations legislation that it will negotiate in coming weeks.

As mentioned above, LGBTQ youth are over-represented in the foster care system. LGBTQ people are at high risk of experiencing violence, homelessness, and poor outcomes that threaten their mental and physical health.[22] Unfortunately, the Administration has put forward two proposed rules — one from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and one from HUD — that would put LGBTQ people, including young people generally and former foster youth specifically, at higher risk of sleeping on the streets or taking dangerous steps to access housing. These rules would prohibit federally funded homeless shelter providers, including those serving runaway and homeless youth, and other social service providers from delivering vital services to this population.[23],[24] Congress should call on the Administration to withdraw the HHS and HUD proposed regulations that would to roll back equal access and anti-discrimination protections for LGBTQ people.