off the charts

POLICY INSIGHT

BEYOND THE NUMBERS

BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Social Security Disability Insurance (DI) maintains high levels of program integrity, despite periodic claims to the contrary, and the program has many safeguards against fraud and abuse.

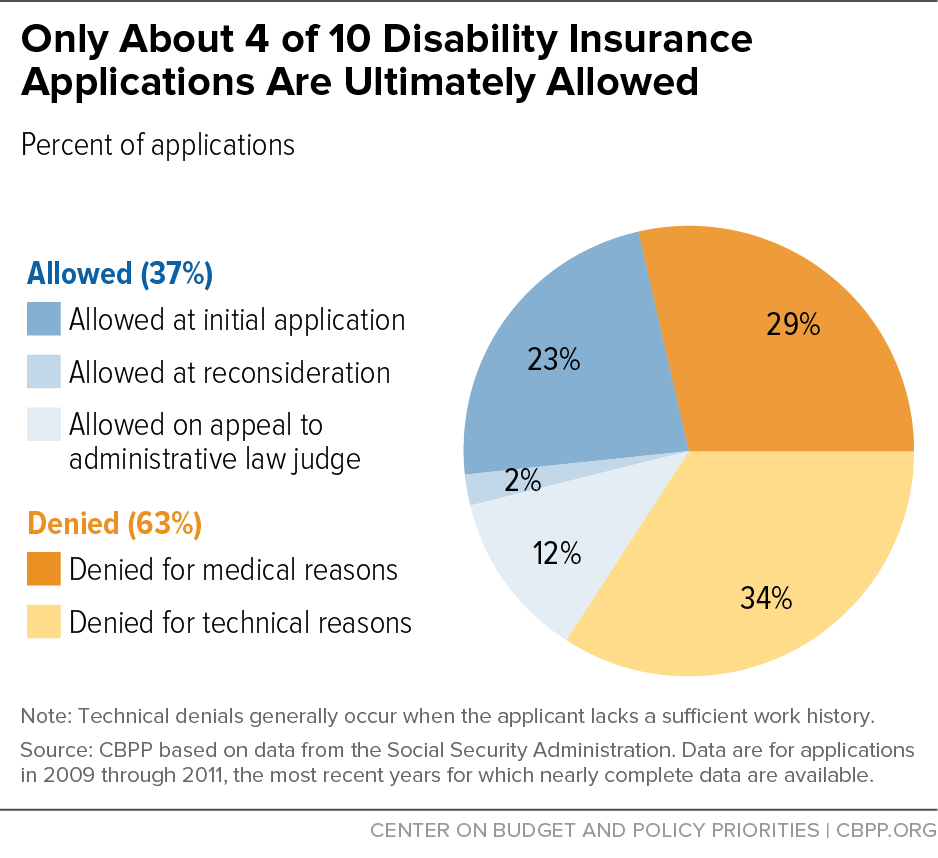

- Strict eligibility standards. DI’s most potent defense against fraud and abuse is strict eligibility rules. By law, DI requires a past work history, a severe and long-lasting impairment that prevents the applicant from doing substantial work and is documented by medical evidence, and a five-month waiting period. These standards are among the toughest among developed countries. Only about 40 percent of DI applicants are awarded benefits (see graph), and there’s little evidence that most beneficiaries could support themselves by working.

- Quality control over disability decisions. The Social Security Administration (SSA) constantly monitors decisions by the states’ Disability Determination Services and its own administrative law judges. Many of these reviews are conducted before a penny of benefits is paid, thus ensuring that SSA keeps errors as low as possible. These reviews consistently find 97 percent or greater accuracy.

- Payment accuracy. DI overpayments averaged less than 1 percent of spending over 2011-2013. “Improper payments” often stem not from fraud but from delays or errors — such as when beneficiaries don’t report their earnings immediately or SSA can’t process them swiftly. SSA aggressively pursues overpayments: half of DI and Supplemental Security Income overpayments over the 2003-2014 period — including three-fourths of the oldest overpayments — were recovered, and only 14 percent were written off, according to a recent study that tracked them through mid-2014.

- Continuing disability reviews. Whereas “upfront” quality reviews aim to make sure that only eligible people receive DI benefits, continuing disability reviews (CDRs) strive to ensure that they don’t receive them for too long. CDRs weed out the relatively few beneficiaries who’ve recovered from their impairments. CDRs save about $10 for each $1 they cost to conduct, but Congress has underfunded them.

- Law enforcement. SSA and its Office of Inspector General (OIG) attack the rare cases of outright fraud — in which applicants or beneficiaries deliberately falsify information to get or keep undeserved benefits. SSA and OIG team with state and local authorities in Cooperative Disability Investigations to investigate suspected fraud. The Disability Fraud Pilot pursues possible fraud involving third parties such as medical providers and attorneys. The agency is working to develop a predictive model and has taken numerous other anti-fraud initiatives. In 2014, OIG received 121,461 fraud allegations; investigated 8,335 that it deemed to have merit; obtained 1,291 criminal convictions, and assessed 412 civil penalties.

Though SSA works hard to fight fraud and reduce improper payments, it could do more — especially if it had the resources and powers to do so. Several bills in Congress would give SSA more legal tools. Crucially, the agency needs stable and predictable funding — as an expert panel of the Social Security Advisory Board and OIG have urged.

As the Bipartisan Policy Center notes, “fraud is not the reason for [DI’s] current funding shortfall.” Lawmakers should support SSA’s anti-fraud efforts, not use fraud as an excuse to gut this vital program.

Topics:

Policy Basics

Retirement Security

Stay up to date

Receive the latest news and reports from the Center