House Republicans and the Trump Administration have sought to justify the House-passed health care bill (the American Health Care Act or AHCA), which would radically restructure Medicaid by converting it to a per capita cap or block grant, by claiming that Medicaid does not work for low-income individuals and families.[2] This claim is false. A wide body of research demonstrates that Medicaid provides critical access to comprehensive, cost-effective care for tens of millions of children and families, seniors, people with disabilities, and other adults. In reality, it’s the AHCA — which would cut federal Medicaid spending by $834 billion over ten years by capping federal Medicaid funding and reducing Medicaid enrollment by 14 million people by 2026, relative to current law[3] — which would eliminate many beneficiaries’ health coverage or access to needed care by forcing states to make increasingly severe Medicaid cuts.

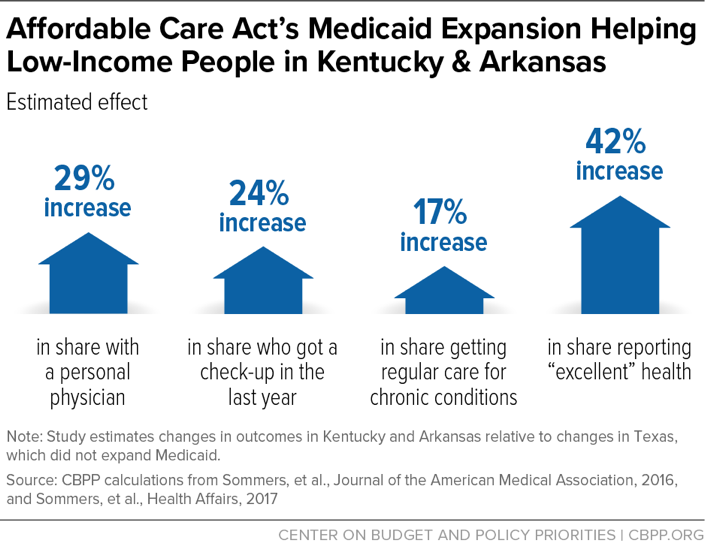

Research shows that Medicaid improves health across a variety of indicators. For example, one recent study compared Arkansas and Kentucky, which have adopted the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion, with Texas, which hasn’t.[4] In the expansion’s first three years, the uninsured rate among the group eligible for expansion coverage dropped more than 20 percentage points more in Arkansas and Kentucky than in Texas. In Arkansas and Kentucky, the expansion fueled a 29 percent increase in the share of people with a personal doctor and a 24 percent increase in the share of people who received a checkup in the past year. With greater access to care came better outcomes: Medicaid expansion resulted in a 42 percent increase in the share of people who said they were “excellent” health. (See Figure 1.) In Arkansas and Kentucky, Medicaid expansion has made people more financially secure: the share of people having trouble paying their medical bills dropped by 25 percent.[5]

Medicaid also produces long-term improvements in health and well-being. For example, among African American children, Medicaid eligibility during early childhood reduced mortality rates in their later teenage years by 13 to 20 percent.[6] In addition, research published in the New England Journal of Medicine reported that expansions of Medicaid coverage for low-income adults in Arizona, Maine, and New York reduced mortality by 6.1 percent.[7] Likewise, the expansion of Medicaid and other health coverage in Massachusetts in 2006 significantly reduced mortality, especially deaths from causes affected by health care.[8] Other studies show that children eligible for Medicaid for more of their childhood earn more as adults and are likelier to attend and complete college.[9] (For a discussion of the findings and limitations of the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, see box.)

In contrast, the AHCA’s cap on Medicaid funding would undermine Medicaid’s positive effects on health by shifting significant costs and risks to states, placing beneficiaries at serious risk of losing their Medicaid coverage entirely or access to needed services.

The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment is a randomized study of Medicaid expansion in Oregon in 2008. Proponents of Medicaid cuts frequently cite this landmark study, claiming it shows that Medicaid beneficiaries’ health outcomes are no better than those of uninsured or even that Medicaid reduces life expectancy.a These claims are not borne out by the study’s findings.

The study showed that Medicaid beneficiaries were likelier than the uninsured to obtain preventive care, such as mammograms for women, and had far less financial hardship caused by health care spending. The researchers also reported significant improvements in diagnosing depression and diabetes among the Medicaid recipients they tracked.

The researchers also noted the study’s limitations, including small sample sizes that prevented them from concluding that some positive trends in the data were statistically significant. For example, some patients’ cholesterol levels fell, but larger samples of patients would be needed before the researchers could be certain of the findings’ validity. Additionally, the results reflect an average of just 17 months of additional health insurance coverage.

While these limitations prevented the researchers from drawing broader conclusions about the effect of Medicaid coverage on long-term health outcomes, they do not undermine the study’s primary finding: that Medicaid gives people access to needed health care. Oregon’s Medicaid beneficiaries used more preventive care — a factor that may take years, or even decades, to show its full effect on their health. b Other studies have shown that Medicaid is also effective in improving beneficiaries’ health.c

a Rick Perry Speaks at the National Press Club, July 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-xOu_o0ugg0; Katie Couric interviews Ted Cruz, Yahoo Politics, June 2015, https://www.yahoo.com/katiecouric/katie-couric-interviews-ted-cruz-ted-cruz-joined-122596925536.html.

b Judith Solomon, “Oregon Medicaid Study Strengthens — Not Weakens — Case to Expand Medicaid,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 3, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/oregon-medicaid-study-strengthens-not-weakens-case-to-expand-medicaid.

c Edwin Park et al., “Frequently Asked Questions About Medicaid,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated March 29, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/frequently-asked-questions-about-medicaid.

Evidence does not support claims that Medicaid fails to provide access to providers and high-quality care. Medicaid beneficiaries have access to health care services that are comparable to — but less costly than — what they would receive from job-based coverage[10] or individual market coverage,[11] with health care quality at least as high as private coverage.[12]

One important measure of access to care is the proportion of people with a regular health care provider. Surveys show that Medicaid beneficiaries have a regular health care provider at rates comparable to people with private coverage and are likelier than people with private coverage to say their care was excellent or very good.

Medicaid beneficiaries are also less likely to forgo seeing a specialist when needed than people with private insurance or those who are uninsured. And, compared to the uninsured, Medicaid beneficiaries and people with private insurance are much likelier to get preventive services[13] and likely to have an unmet need for behavioral health services.[14]

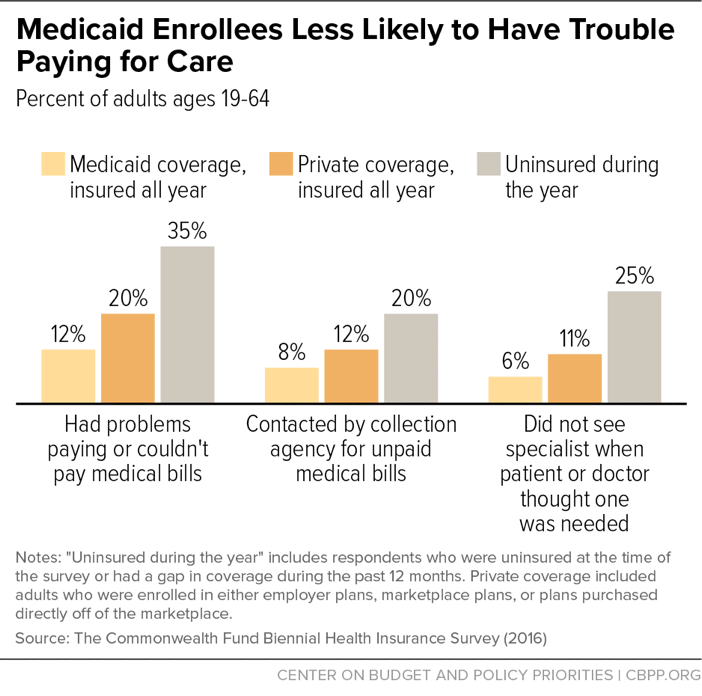

Medicaid also insulates beneficiaries from financial strain. Although beneficiaries typically have low incomes, they are much less likely to have trouble paying for care out of pocket, or to have financial problems due to medical costs, than people with private coverage or those who are uninsured, a survey found.[15] (See Figure 2.) Another study found that people with Medicaid are 40 percent less likely than those without insurance to go into medical debt or leave other bills unpaid in order to cover medical expenses.[16] Yet another found that Medicaid coverage “nearly eliminated catastrophic out-of-pocket medical expenditures.”[17]

Some critics have cited a survey in which 31 percent of primary care physicians in primarily office-based practices said they did not accept new Medicaid patients to argue that Medicaid fails to offer access to care.[18] The survey, however, did not show that Medicaid beneficiaries can’t get the care they need. In fact, the study showed that more doctors accept new Medicaid patients in areas with more Medicaid beneficiaries: in areas with at least 15 percent of people in poverty, providers were about 12 percent likelier to accept new Medicaid patients. This suggests that where the demand for Medicaid providers is higher, physicians are likelier to accept new Medicaid patients.

The study also showed that states that pay providers higher Medicaid rates (rates closer to those paid by Medicare) saw slightly higher provider participation. Thus, cutting federal Medicaid spending and forcing states to cut reimbursement rates — as under the AHCA bill — would reduce access to care.

Medicaid is much more efficient and cost-effective than private insurance: adults on Medicaid cost about 22 percent less than if they were covered by private insurance, after adjusting for differences in health status, Urban Institute research shows.[19] Medicaid also provides more comprehensive benefits than private insurance with significantly lower out-of-pocket cost to beneficiaries.

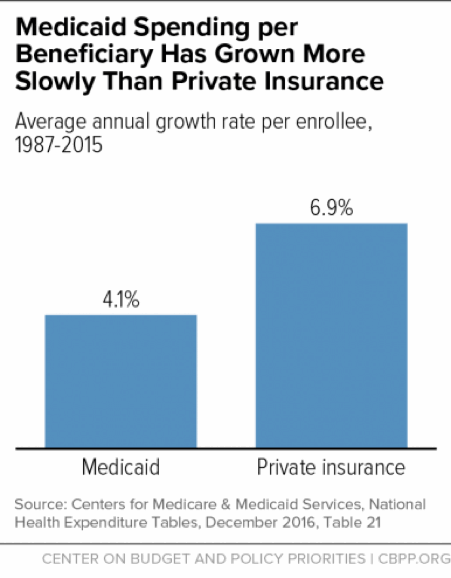

Over the past 30 years, Medicaid costs per beneficiary have essentially tracked costs in the health care system as a whole, public and private. In fact, costs per beneficiary grew much more slowly for Medicaid than for private insurance between 1987 and 2015[20] (see Figure 3) and are expected to continue growing more slowly than for private insurance in coming years, according to both the Urban Institute and the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission.[21]

Medicaid is a federal-state partnership. The federal government pays a set share of each state’s costs, and states follow federal rules setting minimum standards for eligibility, benefits, beneficiary protections, provider payments, and how benefits are delivered. There are some things that states must do, such as making almost all poor children eligible. But states have flexibility, for example, over whether and to what degree to offer benefits such as dental and vision care, physical therapy, and even prescription drugs.

States also are largely free to design their health care delivery systems to meet their beneficiaries’ needs. They can make monthly payments to managed care organizations that are responsible for delivering Medicaid-covered services to their members, or they can set up accountable care organizations, which are groups of providers that agree to coordinate care for groups of beneficiaries in exchange for monthly payments. New options that states received through the ACA, such as the health homes program, have allowed them to provide intensive care coordination to beneficiaries who make unnecessary and frequent visits to the emergency room. Missouri’s health homes program is credited with producing better health outcomes while reducing state costs.[22]

Similarly, Maine launched the Accountable Communities initiative in 2014 as part of a statewide strategy to reward doctors, hospitals, and other providers for offering high-quality health care. The initiative rewards providers for working together to provide physical and behavioral health care, long-term care, and dental care in a coordinated way. If they cut costs while maintaining quality of care, they share in the savings. Program payments reward providers for offering high-value care and keeping costs low.[23]

States, however, need reliable funding in order to continue to innovate. The large and growing Medicaid cuts under the AHCA would significantly limit states’ flexibility to design new ways of providing care. States would have to quickly figure out how to live within fixed, increasingly inadequate amounts of federal funds, making it much harder for them to continue making the upfront investments generally needed to develop systems that can provide high quality care at lower costs over time.