- Inicio

- Tributación Federal

- House Bill Takes Major Steps Forward For...

House Bill Takes Major Steps Forward for Children, Low-Paid Workers

House Ways and Means Committee Chair Richard Neal released a bill yesterday to extend the American Rescue Plan’s increase in the Child Tax Credit amount and its provision as a monthly payment through 2025, while making the full Child Tax Credit permanently available to children in families with the lowest incomes — which is the main driver of the policy’s anti-poverty impact. The expansion in the Child Tax Credit would result in a landmark reduction in poverty, reducing the number of children with incomes below the poverty line by more than 40 percent. The expansion would have particularly large impacts on Black and Latino children and children in rural communities — about half of children in these groups received only a partial credit or no credit at all because their incomes were too low prior to the Rescue Plan expansion. The Child Tax Credit expansion would help narrow gaping racial disparities in child poverty rates.

The bill would also make permanent the Rescue Plan’s expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for adults not raising children at home who work for low pay, largely preventing 5.8 million of them from once again being taxed into, or deeper into, poverty, while helping 17 million adults with low earnings make ends meet.[1]

These are historic policy advances that should remain in the legislation throughout the process and become law. They would promote lifelong opportunity by better protecting children from the damaging effects of poverty and hardship and would largely end the practice of taxing childless adults into or deeper into poverty. In particular, permanently extending the provision that ensures that children in families with the lowest incomes no longer receive less help from the credit than children in families with middle incomes would bring us closer to the ultimate goal of making the landmark full expansion — including the increase in the credit amount — permanent.

The House Ways and Means bill also permanently extends the Rescue Plan’s expansion of the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC). This credit helps offset some of the costs of child care; the Rescue Plan made it, too, fully available to low-income families. The CDCTC expansion would complement an expansion in child care assistance (provided largely through vouchers) that the House Education and Labor Committee approved last week. Taken together, these measures would help many more families afford the high cost of child care, easing pressure on family budgets and enabling more parents to work.

Child Tax Credit Improvements Would Raise Millions of Children Above the Poverty Line

Since the Child Tax Credit’s creation in 1997, policymakers have worked on a bipartisan basis, involving every administration, both to increase the credit’s maximum amount and to make the credit available to more children in families with low or moderate incomes. This year’s American Rescue Plan took the boldest steps to date in both areas. The Ways and Means bill would extend its increase in the credit through 2025 and make the provision that provides the full credit to the lowest-income children permanent.

The Rescue Plan raised the maximum credit from $2,000 to $3,000 for children ages 6-17 (including 17-year-olds for the first time) and to $3,600 for children under age 6. It also provided that the credit be allocated as a monthly payment. Those improvements are only for 2021, however. The Ways and Means bill would extend the increase in the credit amount and the monthly payment mechanism through 2025. The bill also would index the increased credit amount over time by inflation. Under the Ways and Means bill, the increase in the maximum credit begins to phase down for unmarried tax filers making more than $112,500 and for married couples making over $150,000. (The underlying, $2,000-per-child credit begins to phase out at higher income levels.)

Critically, the Rescue Plan also ensured, for the first time, that millions of families with low incomes would get the full credit — but, again, only for one year. (This change is sometimes called making the credit “fully refundable.”) The Ways and Means bill makes this change permanent.

Prior to the Rescue Plan, an estimated 27 million children received less than the full credit or no credit at all because their families lacked earnings or had earnings that were too low.[2] (See Table 1.) They included roughly half of all Black children and half of all Latino children, whose families (along with other families of color) are overrepresented in low-paid work and face worse employment prospects due to historical and ongoing discrimination in education, housing, employment, and criminal justice that has systematically limited opportunity.[3] (By comparison, about 20 percent of white children received less than the full credit or no credit at all because their families’ incomes were too low.) Similarly, about half of children who live in rural areas also received a partial credit or no credit at all because their families’ incomes were too low, reflecting lower incomes and higher poverty levels in many rural communities; median annual wages for year-round workers are lower (by roughly 19 percent) in rural than in metropolitan areas.[4]

This upside-down policy gave less help to the very children who needed it most. The Rescue Plan fixed this policy on a temporary basis, and the Ways and Means bill would ensure on a permanent basis that children in families with low incomes receive the same credit as children in middle-income families.

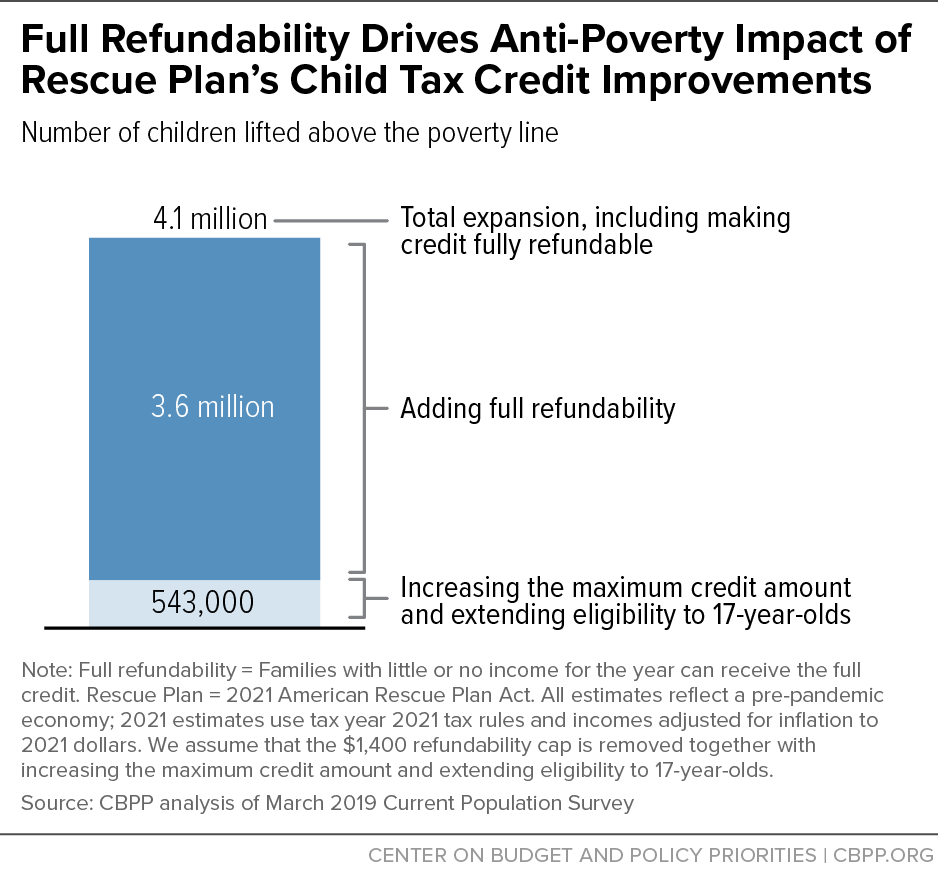

Making the credit fully refundable has a major anti-poverty impact for children. Extending the Rescue Plan’s credit improvements other than full refundability — that is, raising the maximum amount and adding 17-year-olds — would only lift an estimated 543,000 children above the poverty line, reducing child poverty by 5 percent. That’s because most children with incomes below the poverty line didn’t receive the full credit prior to the Rescue Plan, so increasing the credit doesn’t benefit them. But those changes plus full refundability would raise 4.1 million children above the poverty line and cut child poverty by more than 40 percent.[5] (See Figure 1.)

In other words, the full refundability component makes the overall Child Tax Credit expansion nearly eight times as effective in reducing child poverty.

An example illustrates the power of the Child Tax Credit expansion in the Ways and Means bill. A single mother with a toddler and a second-grader, who works part-time as a home health aide and earns $12,000 a year, would see her credit increase from about $1,425 before the Rescue Plan expansion (which was $2,575 less than middle- and high-income families received) to $6,600 under the Rescue Plan and Ways and Means expansions — which would be an economic game changer for her children. Moreover, as under the Rescue Plan, the family would receive the credit on a monthly basis under the Ways and Means bill, making it easier for the mother to use the credit to meet her monthly expenses.

Most families benefiting from the expansion include an adult who works in that year. But it would also help families with parents who are out of work, most of whom are between jobs or who have health or other issues preventing them from working at least temporarily.

In addition, the Ways and Means bill would also extend the Child Tax Credit expansion to all the U.S. territories.

Importantly, the Ways and Means bill would also restore eligibility for the Child Tax Credit to children who aren’t eligible for a Social Security number because of their immigration status but may be claimed as tax dependents by using an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN). A provision in the 2017 tax law denied the credit to such children — even though there is broad support to grant them legal status and ensure that their families, like others, have the resources to meet their children’s needs and help them thrive. Repealing this provision, as the Ways and Means bill does, would give children with ITINs access to the same credit as other children.

Overall, the Child Tax Credit expansion is expected to benefit more than 65 million children, generating landmark reductions in poverty among children and in the gaping disparities in poverty rates by race and ethnicity.[6] The impact would go well beyond reducing near-term hardship. Research shows that poverty and its attendant hardships shortchange children’s futures.[7] Research also shows that additional family income improves outcomes for children in areas including education, earnings in adulthood, and health, which can yield benefits over the course of their lives that also benefit the nation as a whole.[8]

Important Improvements to Monthly Payment Provisions, Mechanisms for Facilitating Enrollment

The Ways and Means bill would make important improvements to the monthly delivery structure starting in 2023 (though the credit would be delivered monthly in 2022 as well). For example, starting in 2023, eligibility would be determined on a monthly rather than annual basis to help ensure that the monthly payments follow the child if their caregiver changes during the course of the year, once the new caregiver informs the IRS of the change. This means that if a child lives with both parents and the credit payment goes into a joint bank account and then the parents split up and the child goes to live with the mother, the payment can follow the child and start going to the mother’s account — regardless of when during the year the child’s living situation changes. Or, if a child can’t be cared for by a parent and goes to live with their grandparent, the payment can switch to the grandparent, once the grandparent notifies the IRS.

The bill also proposes critical IRS funding to administer the credit and for outreach and enrollment efforts to increase the number of children — particularly those in families that have not traditionally filed a tax return — who participate. The bill authorizes the Treasury Department to develop mechanisms to enroll newborns in the Child Tax Credit and to use information from other sources to facilitate enrollment of children who appear eligible for, but are not receiving, the monthly credit. The bill also requires the IRS to maintain online portals for families to enroll in Child Tax Credit payments and update their information during the year. (The Biden Administration created an online portal and has taken steps to make mobile-friendly and Spanish-language non-filer tools available this year.[9])

Since the first monthly payments of the expanded Child Tax Credit were issued on July 15, families with low and moderate incomes largely spent their initial payments on meeting essential needs, including food, utilities, clothing, and housing, and paid down debt (including overdue utility bills). The number of adults with children who said their household didn’t have enough to eat dropped significantly after the payments started, according to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. Many families also focused their spending on education, such as school books and supplies.[10]

Permanent EITC Improvements for Millions of Low-Paid Working Adults

The EITC is a powerful wage subsidy, but before the Rescue Plan it largely excluded workers without children at home, providing only a tiny credit to a small number of them, and excluding younger and older workers. The Ways and Means bill would fix this glaring flaw on a permanent basis by extending Rescue Plan provisions that raised both the maximum EITC for these workers (from roughly $540 to roughly $1,500) and the income cap for them to qualify (from about $16,000 to at least $21,000). It would also permanently expand the age range of eligible workers without children to include younger adults aged 19-24 (excluding students under 24 who are attending school at least part time), as well as people aged 65 and over.

This expansion would boost the income of more than 17 million working adults without children who do important work for low pay. (See Table 2.) They include 5.8 million people ages 19 to 65 whom the federal tax code would otherwise tax into, or deeper into, poverty — the lone group for whom that happens — in large part because their EITC would be too low without an extension of the Rescue Plan’s expansions.[11] The shares of such people who are Latino and Black workers are disproportionately high (about 26 percent are Latino and 18 percent are Black, compared to their 19 percent and 12 percent shares of the overall population, respectively) — again reflecting historical barriers to economic opportunity that have led to their overrepresentation in low-paid work.

| TABLE 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before American Rescue Plan Expansion, Child Tax Credit Partly or Entirely Excluded 27 Million Children Due to Low or No Family Earnings | ||||||

| State | Total | White | Latino | Black | Asian | Another race or multiple races |

| Total U.S. | 27,000,000 | 8,763,000 | 9,904,000 | 5,738,000 | 813,000 | 1,782,000 |

| Alabama | 480,000 | 181,000 | 55,000 | 220,000 | 3,000 | 22,000 |

| Alaska | 53,000 | 15,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 27,000 |

| Arizona | 692,000 | 153,000 | 407,000 | 39,000 | 8,000 | 84,000 |

| Arkansas | 323,000 | 157,000 | 56,000 | 86,000 | N/A | 22,000 |

| California | 3,524,000 | 450,000 | 2,480,000 | 227,000 | 221,000 | 146,000 |

| Colorado | 346,000 | 120,000 | 176,000 | 19,000 | 8,000 | 22,000 |

| Connecticut | 199,000 | 53,000 | 92,000 | 37,000 | 7,000 | 10,000 |

| Delaware | 67,000 | 19,000 | 17,000 | 26,000 | N/A | N/A |

| District of Columbia | 53,000 | N/A | 8,000 | 43,000 | N/A | N/A |

| Florida | 1,730,000 | 466,000 | 657,000 | 498,000 | 26,000 | 84,000 |

| Georgia | 1,044,000 | 273,000 | 221,000 | 473,000 | 21,000 | 57,000 |

| Hawai’i | 92,000 | 9,000 | 19,000 | N/A | 16,000 | 47,000 |

| Idaho | 153,000 | 95,000 | 46,000 | N/A | N/A | 10,000 |

| Illinois | 982,000 | 295,000 | 352,000 | 265,000 | 26,000 | 44,000 |

| Indiana | 558,000 | 307,000 | 96,000 | 107,000 | 11,000 | 36,000 |

| Iowa | 197,000 | 120,000 | 32,000 | 24,000 | 5,000 | 16,000 |

| Kansas | 218,000 | 106,000 | 65,000 | 23,000 | 4,000 | 20,000 |

| Kentucky | 422,000 | 292,000 | 38,000 | 59,000 | 5,000 | 27,000 |

| Louisiana | 530,000 | 160,000 | 41,000 | 296,000 | 5,000 | 28,000 |

| Maine | 75,000 | 62,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6,000 |

| Maryland | 352,000 | 82,000 | 85,000 | 148,000 | 13,000 | 24,000 |

| Massachusetts | 356,000 | 119,000 | 146,000 | 50,000 | 21,000 | 22,000 |

| Michigan | 810,000 | 406,000 | 97,000 | 232,000 | 16,000 | 60,000 |

| Minnesota | 322,000 | 133,000 | 57,000 | 74,000 | 23,000 | 36,000 |

| Mississippi | 351,000 | 103,000 | 16,000 | 215,000 | N/A | 15,000 |

| Missouri | 502,000 | 296,000 | 46,000 | 112,000 | 5,000 | 43,000 |

| Montana | 78,000 | 51,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 21,000 |

| Nebraska | 141,000 | 65,000 | 47,000 | 13,000 | 5,000 | 11,000 |

| Nevada | 271,000 | 53,000 | 142,000 | 42,000 | 10,000 | 23,000 |

| New Hampshire | 52,000 | 40,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| New Jersey | 561,000 | 144,000 | 252,000 | 122,000 | 23,000 | 20,000 |

| New Mexico | 245,000 | 34,000 | 166,000 | 3,000 | N/A | 42,000 |

| New York | 1,552,000 | 471,000 | 574,000 | 316,000 | 123,000 | 69,000 |

| North Carolina | 926,000 | 300,000 | 241,000 | 300,000 | 18,000 | 66,000 |

| North Dakota | 39,000 | 20,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 12,000 |

| Ohio | 950,000 | 512,000 | 91,000 | 249,000 | 11,000 | 88,000 |

| Oklahoma | 398,000 | 153,000 | 100,000 | 51,000 | 4,000 | 90,000 |

| Oregon | 291,000 | 146,000 | 102,000 | 10,000 | 8,000 | 25,000 |

| Pennsylvania | 893,000 | 428,000 | 192,000 | 196,000 | 25,000 | 54,000 |

| Rhode Island | 67,000 | 22,000 | 30,000 | 8,000 | N/A | N/A |

| South Carolina | 476,000 | 156,000 | 66,000 | 220,000 | 4,000 | 30,000 |

| South Dakota | 67,000 | 28,000 | 6,000 | N/A | N/A | 30,000 |

| Tennessee | 635,000 | 314,000 | 93,000 | 188,000 | 7,000 | 33,000 |

| Texas | 3,086,000 | 476,000 | 2,040,000 | 430,000 | 60,000 | 79,000 |

| Utah | 233,000 | 129,000 | 74,000 | N/A | 4,000 | 19,000 |

| Vermont | 30,000 | 26,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Virginia | 532,000 | 194,000 | 102,000 | 179,000 | 17,000 | 39,000 |

| Washington | 477,000 | 191,000 | 173,000 | 32,000 | 20,000 | 61,000 |

| West Virginia | 170,000 | 145,000 | 4,000 | 9,000 | N/A | N/A |

| Wisconsin | 366,000 | 171,000 | 75,000 | 73,000 | 13,000 | 34,000 |

| Wyoming | 35,000 | 22,000 | 8,000 | N/A | N/A | 4,000 |

Notes: Figures are rounded to the nearest 1,000 and may not sum to totals due to rounding. N/A indicates reliable data are not available due to small sample size. Estimates reflect a pre-pandemic economy, using tax year 2021 tax rules and incomes adjusted for inflation to 2021 dollars. Children partly or entirely excluded from the credit (meaning their families received less than the full credit or none at all prior to the Rescue Plan) are those under age 17 whose families lacked earnings or had earnings that were too low. Racial and ethnic categories do not overlap; figures for each racial group such as Black, white, or Asian do not include individuals who identify as multiracial or people of Latino ethnicity. Latino includes all people of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin regardless of race. Due to limitations of the Census data, the figures do not reflect IRS rules that require children to have a Social Security number to qualify for the Child Tax Credit. This omission likely has little effect on most of the estimates shown here; the Latino share of children left out, however, may be somewhat overstated.

Source: Tax Policy Center national estimate allocated by state and by race or ethnicity based on CBPP analysis of American Community Survey data for 2016-2018.

| TABLE 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 Million Working Adults Without Children Would Benefit Each Year From Permanently Extending Rescue Plan’s EITC Expansion Relative to before Rescue Plan’s temporary expansion | ||||||

| State | Total | White | Latino | Black | Asian | Another race or multiple races |

| Total U.S. | 17,445,400 | 9,658,700 | 3,639,600 | 2,739,300 | 815,700 | 592,100 |

| Alabama | 274,300 | 157,100 | 15,200 | 92,000 | 4,000 | 6,000 |

| Alaska | 38,900 | 20,400 | N/A | N/A | 3,100 | 10,500 |

| Arizona | 385,200 | 196,800 | 130,900 | 22,700 | 10,800 | 24,000 |

| Arkansas | 173,700 | 118,500 | 12,800 | 34,200 | 2,800 | 5,300 |

| California | 2,070,100 | 668,800 | 941,300 | 138,100 | 247,600 | 74,300 |

| Colorado | 293,300 | 197,700 | 61,600 | 15,200 | 8,900 | 10,000 |

| Connecticut | 160,900 | 88,700 | 37,100 | 23,800 | 6,100 | 5,300 |

| Delaware | 46,500 | 25,500 | 4,600 | 13,200 | 1,500 | 1,700 |

| District of Columbia | 33,200 | 9,100 | 4,500 | 17,300 | N/A | N/A |

| Florida | 1,323,000 | 629,200 | 401,300 | 232,400 | 30,500 | 29,700 |

| Georgia | 569,900 | 261,700 | 62,700 | 214,600 | 18,600 | 12,300 |

| Hawai’i | 71,700 | 17,100 | 7,300 | N/A | 24,100 | 21,700 |

| Idaho | 104,300 | 86,200 | 13,100 | N/A | N/A | 3,500 |

| Illinois | 620,700 | 353,100 | 113,500 | 113,100 | 28,800 | 12,300 |

| Indiana | 367,100 | 273,700 | 27,100 | 47,900 | 8,000 | 10,500 |

| Iowa | 171,400 | 146,200 | 9,000 | 9,400 | 3,100 | 3,600 |

| Kansas | 163,700 | 118,900 | 20,100 | 15,700 | 2,900 | 6,100 |

| Kentucky | 256,000 | 205,600 | 11,200 | 30,600 | 2,900 | 5,700 |

| Louisiana | 281,900 | 137,600 | 17,800 | 115,900 | 4,900 | 5,700 |

| Maine | 85,300 | 79,400 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2,400 |

| Maryland | 263,300 | 115,400 | 36,600 | 87,600 | 16,200 | 7,400 |

| Massachusetts | 299,500 | 197,200 | 46,500 | 26,800 | 19,500 | 9,500 |

| Michigan | 571,000 | 407,600 | 33,300 | 98,900 | 13,700 | 17,700 |

| Minnesota | 276,300 | 210,800 | 17,900 | 23,100 | 11,700 | 12,800 |

| Mississippi | 166,500 | 79,600 | 6,500 | 76,400 | 1,900 | 2,200 |

| Missouri | 338,800 | 257,400 | 15,800 | 50,500 | 6,500 | 8,600 |

| Montana | 77,900 | 67,800 | 2,600 | N/A | N/A | 6,100 |

| Nebraska | 101,000 | 75,900 | 11,900 | 7,300 | N/A | 3,600 |

| Nevada | 175,300 | 78,100 | 53,500 | 20,100 | 14,400 | 9,100 |

| New Hampshire | 66,400 | 59,900 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| New Jersey | 388,400 | 168,600 | 116,700 | 69,300 | 25,200 | 8,700 |

| New Mexico | 132,000 | 48,500 | 64,100 | 4,300 | 1,800 | 13,300 |

| New York | 982,700 | 463,500 | 235,500 | 158,900 | 98,100 | 26,600 |

| North Carolina | 593,900 | 334,300 | 63,800 | 161,200 | 13,800 | 20,700 |

| North Dakota | 39,300 | 29,100 | 2,900 | N/A | N/A | 3,300 |

| Ohio | 651,600 | 473,900 | 27,500 | 119,200 | 13,000 | 17,900 |

| Oklahoma | 229,200 | 141,900 | 26,500 | 25,100 | 3,700 | 32,000 |

| Oregon | 255,300 | 191,100 | 35,700 | 6,200 | 9,900 | 12,300 |

| Pennsylvania | 662,700 | 475,200 | 59,000 | 93,700 | 21,200 | 13,500 |

| Rhode Island | 47,600 | 32,300 | 9,300 | 2,500 | N/A | N/A |

| South Carolina | 303,300 | 164,800 | 21,600 | 104,600 | 4,800 | 7,400 |

| South Dakota | 49,800 | 37,500 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 8,200 |

| Tennessee | 381,400 | 262,100 | 25,100 | 80,500 | 6,300 | 7,400 |

| Texas | 1,505,300 | 532,800 | 674,800 | 212,800 | 55,100 | 29,700 |

| Utah | 142,300 | 103,600 | 26,100 | N/A | 4,700 | 5,800 |

| Vermont | 37,200 | 34,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Virginia | 415,700 | 230,000 | 46,600 | 105,000 | 20,900 | 13,300 |

| Washington | 358,300 | 233,300 | 54,600 | 19,500 | 24,800 | 26,100 |

| West Virginia | 102,900 | 90,200 | 2,700 | 7,300 | N/A | 1,700 |

| Wisconsin | 303,700 | 240,700 | 18,500 | 28,300 | 6,600 | 9,600 |

| Wyoming | 35,500 | 30,400 | 2,900 | N/A | N/A | 1,700 |

Note: Figures are rounded to the nearest 100 and may not sum to totals due to rounding. N/A indicates reliable data are not available due to small sample size. Estimates reflect a pre-pandemic economy, using tax year 2021 tax rules and incomes adjusted for inflation to 2021 dollars. Working adults without children counted as benefiting from the EITC expansion are those aged 19 and older (excluding students under age 24 attending school at least part time). Racial and ethnic categories do not overlap; figures for each racial group such as Black, white, or Asian do not include individuals who identify as multiracial or people of Latino ethnicity. Latino includes all people of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin regardless of race. Due to limitations of the Census data, the figures do not reflect IRS rules that require all EITC family members to have a Social Security number. This omission likely has little effect on most of the estimates shown here; the Latino share of those benefiting, however, may be somewhat overstated.

Source: CBPP analysis of the Census Bureau’s March 2019 Current Population Survey (for national total) allocated by state and by race or ethnicity based on CBPP analysis of American Community Survey data for 2016-2018.

Más sobre este tema

Recovery Package Should Permanently Include Families With Low Incomes in Full Child Tax Credit

Compendios de política pública

Tributación federal

End Notes

[1] Chuck Marr et al., “Congress Should Adopt American Families Plan’s Permanent Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC, Make Additional Provisions Permanent,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 24, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/congress-should-adopt-american-families-plans-permanent-expansions-of-child.

[2] Marr et al., op. cit.

[3] Sophie Collyer, David Harris, and Christopher Wimer, “Left behind: The one-third of children in families who earn too little to get the full Child Tax Credit,” Center on Poverty & Social Policy at Columbia University, May 14, 2019, https://www.povertycenter.columbia.edu/news-internal/leftoutofctc; Danilo Trisi and Matt Saenz, “Economic Security Programs Reduce Overall Poverty, Racial and Ethnic Inequities,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated July 1, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/economic-security-programs-reduce-overall-poverty-racial-and-ethnic. Even in the relatively strong pre-pandemic economy, 1 in 3 Black (33 percent) and Latino (34 percent) workers earned below-poverty wages, as did nearly 1 in 5 white workers (19 percent). Economic Policy Institute, State of Working America Data Library, “Poverty-level wages,” 2019, https://www.epi.org/data/#?subject=povwage.

[4] Rural communities are diverse: about one-quarter of rural residents identify as Black, Latino, Asian, American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander, or identify with more than one race. Chuck Marr et al., “Expanding Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit Would Benefit More Than 10 Million Rural Residents, Strongly Help Rural Areas,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 6, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/expanding-child-tax-credit-and-earned-income-tax-credit-would-benefit-more.

[5] Chuck Marr, Kris Cox, and Arloc Sherman, “Recovery Package Should Permanently Include Families With Low Incomes in Full Child Tax Credit,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 7, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/recovery-package-should-permanently-include-families-with-low-incomes-in-full.

[6] Marr et al., op. cit., see https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/congress-should-adopt-american-families-plans-permanent-expansions-of-child#table4.

[7] National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, “A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty,” 2019, https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25246/a-roadmap-to-reducing-child-poverty.

[8] See Arloc Sherman et al., “Recovery Proposals Adopt Proven Approaches to Reducing Poverty, Increasing Social Mobility,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 5, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/recovery-proposals-adopt-proven-approaches-to-reducing-poverty; Claire Zippel and Arloc Sherman, “Bolstering Family Income Is Essential to Helping Children Emerge Successfully From the Current Crisis,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 25, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/bolstering-family-income-is-essential-to-helping-children-emerge.

[9] The White House, “Child Tax Credit for Non-Filers,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/child-tax-credit/sign-up/.

[10] Claire Zippel, “After Child Tax Credit Payments, Many More Families Have Enough to Eat,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 30, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/after-child-tax-credit-payments-begin-many-more-families-have-enough-to-eat.

[11] Marr et al., May 24, 2021.

Más de los autores

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work: