As the House and Senate appropriations committees begin work on appropriations for fiscal year 2023, they should set overall non-defense appropriations at a level adequate to meet national priorities, remedy shortfalls that hamper delivery of government services, and help build a stronger, more equitable economy. The 2023 budget proposed by the Biden Administration provides a good roadmap in these and other areas.

This year’s appropriations should be seen in the context of relative austerity over the past decade, resulting largely from the caps set by the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA). The BCA imposed tight annual caps on defense and non-defense appropriations (often referred to as “non-defense discretionary” or NDD funding) from 2012 through 2021. The starting point for those caps was the 2011 level, effectively locking in substantial cuts in non-defense programs that had been made that year. Under the BCA, NDD appropriations reached a low point in 2013.

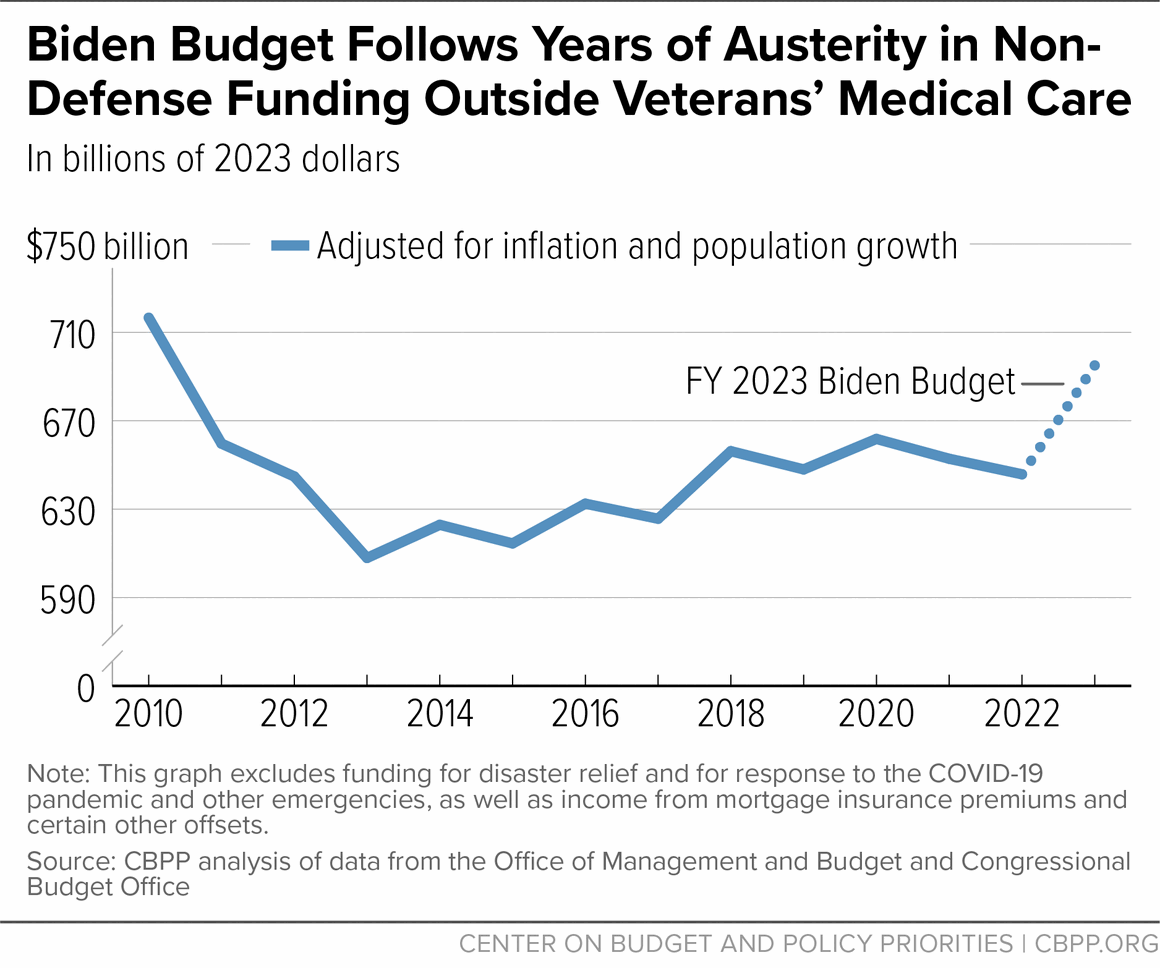

While NDD funding has grown since that low point, looking over multi-year periods requires accounting for factors that affect costs and needs. Prices, and hence program costs, rise over time. The nation’s population also continues to grow, increasing the number of people that the federal government serves while spreading the costs of the programs among a greater population. Adjusted for inflation and population growth, while overall NDD funding has risen above the BCA’s low point in 2013, by 2022 it was still 4 percent below what it had been in 2010.

Non-defense appropriations support a wide range of important functions. Those include education and job training, medical care for veterans, housing and other assistance for families with low income, financial aid for college students, public health measures and other health services, scientific and medical research, management of national parks and forests, the Internal Revenue Service, administration of Social Security and Medicare, weather forecasting and warnings, the Coast Guard, international assistance, air traffic control, rural development, and upgrades to wastewater and drinking water treatment.

Within the non-defense category, medical care for veterans is by far the largest program. Its funding has been rising much more rapidly than the overall NDD total, due to factors such as increasing numbers of veterans using the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health system, rising health care costs in general, and some expansion of health benefits. Overall funding for NDD programs other than veterans’ medical care, in contrast, remains 10 percent below its 2010 level adjusted for inflation and population growth.

Because of these divergent trends, it’s important to look beyond the total for NDD programs when assessing funding levels, to ensure that sufficient funding is provided to take care of both veterans’ medical care needs and other priorities as well. The President’s budget for 2023 reinforces that point by displaying veterans’ medical care as a separate category from the rest of NDD programs.

The budget proposes a 21 percent increase for veterans’ medical care and a 12 percent increase in NDD programs outside of veterans’ health. The two categories combined would increase by 14 percent.

| TABLE 1

|

|

|

|

|

Change, 2022 to 2023

|

|

|

FY 2022

|

FY 2023

|

Dollar

|

Percent

|

| Veterans’ Medical Care

|

101.9

|

123.8

|

21.9

|

21%

|

| All Other NDD Programs

|

619.5

|

695.1

|

75.6

|

12%

|

| Veterans’ Medical Care and All Other NDD Programs

|

721.5

|

818.9

|

97.4

|

14%

|

The increase for programs outside of veterans’ medical care would support a diverse range of priorities, such as maintaining and modestly expanding housing assistance, boosting funding to improve equity in elementary and secondary education, increasing Pell Grants to help students with modest incomes afford college, and increasing child care assistance and Head Start funding. It would also reduce serious funding shortfalls at agencies such as the Social Security Administration, Internal Revenue Service, and Environmental Protection Agency, and enable them to better carry out their missions.

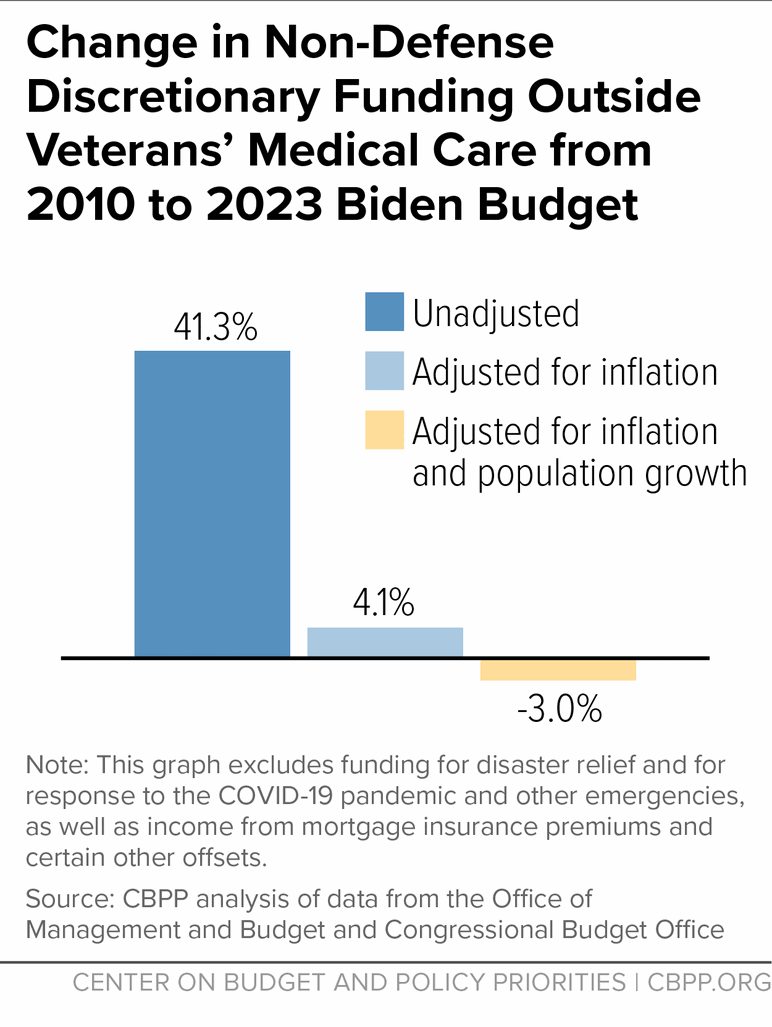

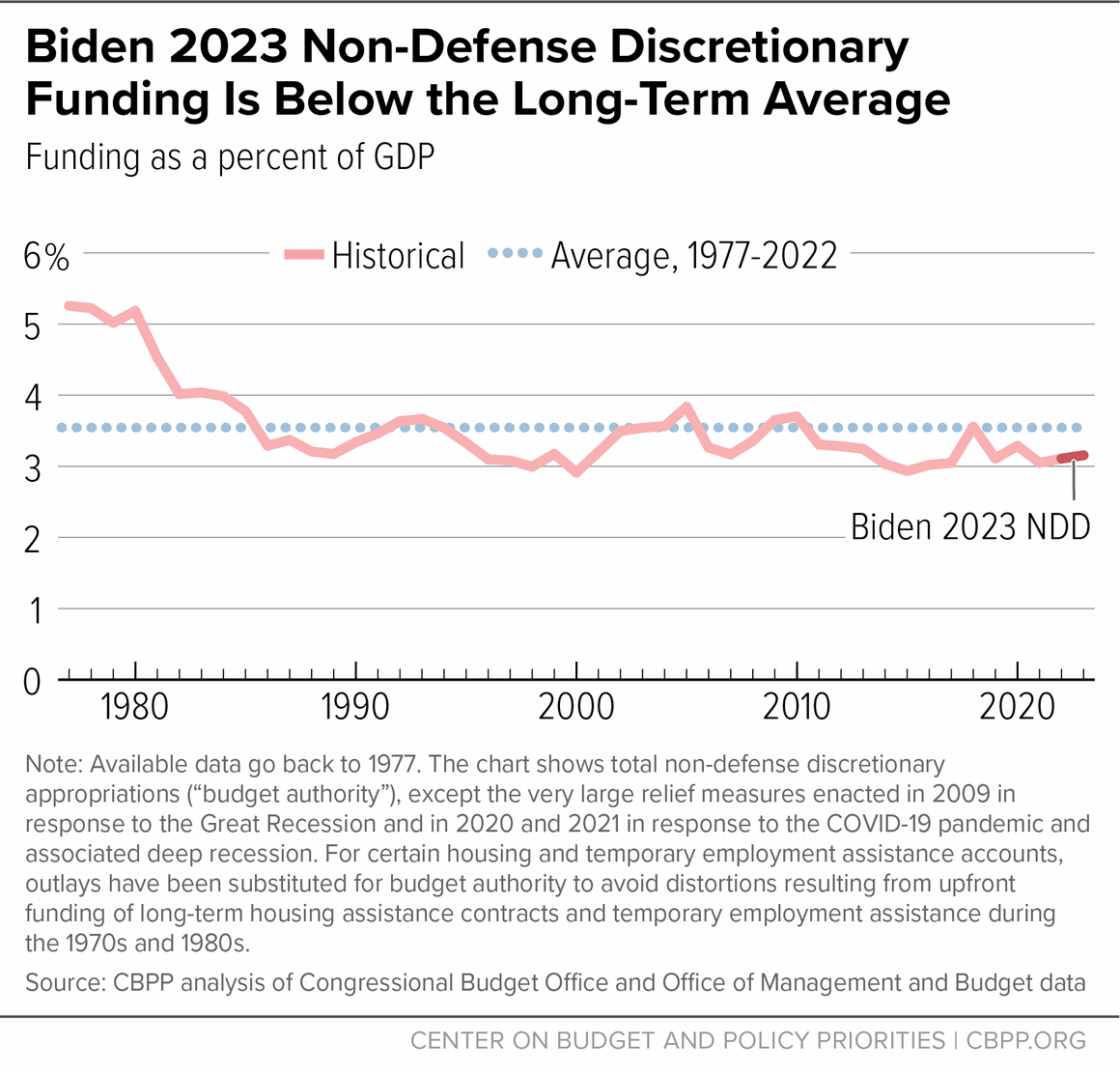

Even enactment of the full Biden proposals, however, would not completely reverse the remaining cuts made under the BCA; they would still leave NDD programs outside of veterans’ medical care 3 percent below where it was in 2010 after adjusting for inflation and population growth. Some budget categories would be above their 2010 levels while others would remain below. As a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) — a standard way of examining budget trends over long periods — NDD funding in 2023 would be less than the long-term average going back to 1977.

Due to its large size and rapid growth, funding for veterans’ medical care[1] through the VA has risen markedly in recent years and is slated to continue to increase in coming years.[2] These services are almost entirely supported through annual appropriations. Historically Congress has sought to provide the full amount necessary to meet the needs of eligible veterans seeking care. If veterans’ medical care funding is considered as part of the overall NDD total, increased funding for that care can squeeze out funding priorities in other NDD programs. Moreover, a sizable increase in funding for veterans’ medical care can make it seem that NDD overall is receiving a significant funding increase when that may be true mostly for veterans’ health programs.

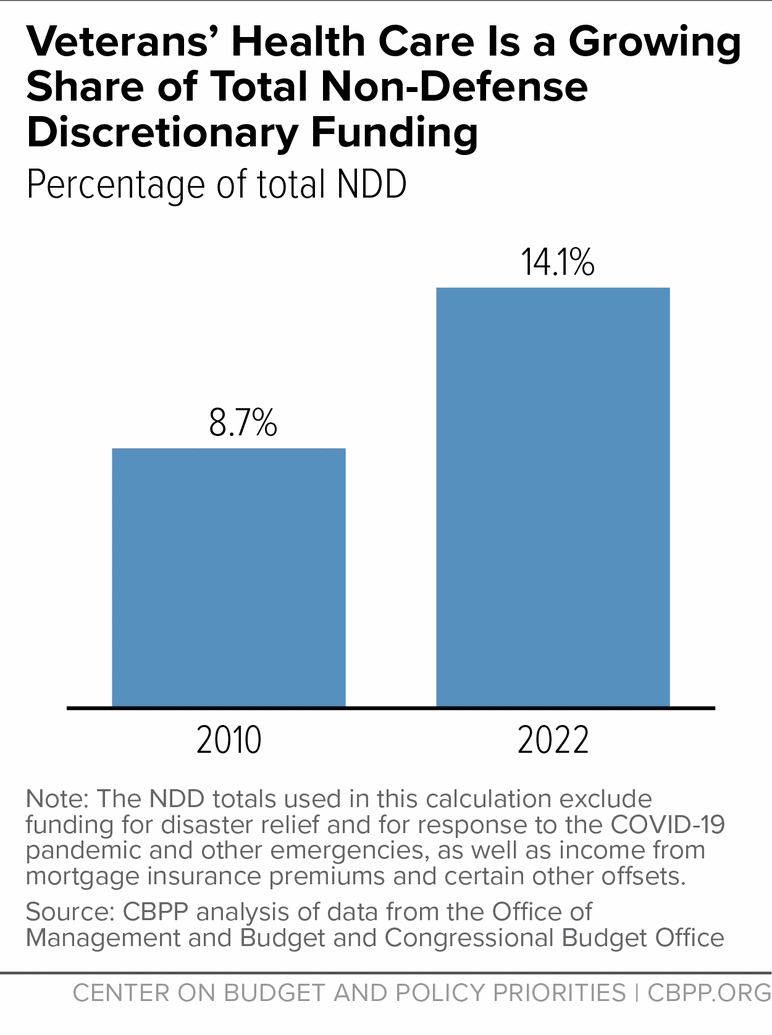

Appropriations for veterans’ medical care totaled $102 billion in 2022 and represented about one-seventh of the NDD total. Between 2010 and 2022, funding for veterans’ medical care rose by 55 percent after adjustment for inflation and population growth. Since this growth was considerably larger than funding growth for the rest of NDD, the veterans’ medical care share of the overall NDD total rose from 8.7 percent in 2010 to 14.1 percent in 2022. (See Figure 1.)

In part, these increases reflect a growing number of eligible patients using the VA system, which increased by 22 percent between 2010 and 2022,[3] accompanied by increased intensity of use of VA services. Veterans’ medical care is also subject to many of the same cost pressures as other health care, where costs tend to grow faster than general inflation. Another factor is expansions or improvements in benefits, such as through the 2018 MISSION Act and predecessor legislation, which expanded opportunities for veterans to seek care from community providers rather than solely in VA facilities. The Act also improved assistance, including stipends, to family caregivers of seriously injured veterans.[4] Further, costs have risen due to the pandemic. The VA also expects that many veterans will soon be returning for other care and procedures that had been postponed during the height of the pandemic — care that may have become more expensive because of the delay.[5]

To meet rising costs, the President’s budget calls for a sharp acceleration in the growth rate of veterans’ medical care funding, from a 7 percent increase in 2022 to a 21 percent ($22 billion) increase in 2023. That increase alone would produce a 3 percent increase in the overall NDD total in 2023.

Given that VA medical costs have grown more rapidly than other NDD programs, in its 2023 budget the Biden Administration calls for treating veterans’ medical care as a third basic category of appropriations, separate from both defense and other non-defense. This has some appeal, as veterans’ programs straddle the line between the two categories. Eligibility is based on military service and VA care often treats injuries or serious health problems arising from that service, but the VA is considered a civilian agency. Since VA costs are directly related to policy decisions about the size of the military and the use of force around the world, the VA budget could just as well have been combined into a budget category with the defense agencies rather than with the non-defense agencies.

Moreover, Congress treats veterans’ medical care differently than most, though not all, other NDD programs by appropriating the full amount believed necessary to take care of everyone eligible. The Biden Administration also makes clear that separate treatment for veterans’ medical care is related to ensuring that Congress provides adequate funding for non-defense appropriations outside of veterans’ medical care to address other national priorities as well.[6] By explicitly setting funding levels across three budget categories — defense, VA medical care, and NDD programs (outside of VA health) — those funding decisions would be more transparent. Even if Congress does not explicitly adopt three appropriations categories, it will be important to look at the funding level for NDD programs outside of veterans’ medical care separately from NDD programs including veterans’ medical care.

The proposed substantial increase in NDD funding outside of veterans’ medical care should be seen in the context of the relative austerity for NDD programs that preceded it, resulting from the BCA.

For the current fiscal year, 2022, Congress enacted appropriations providing a 6 percent overall increase for non-defense programs excluding veterans’ medical care — about 1 percentage point less than what would be needed just to keep pace with inflation and population growth. The resulting 2022 level is still 10 percent below 2010 after adjusting for those factors.

The budget for 2023 proposes an increase of 12 percent for non-defense appropriations outside veterans’ medical care. Enactment of the full increase would fall a little short of getting that funding back to the 2010 level — leaving it 3 percent below on an inflation- and population-adjusted basis. (See figures 2 and 3.)

Further, returning to the 2010 level 13 years later would not make up for the shortfalls that occurred in between, which meant less investment in maintaining and upgrading technology and facilities, less progress in addressing inequalities, less support for infrastructure investments, less scientific research, and poorer service to the public, among other consequences. Some of those represent permanently lost opportunities, but things like unaddressed maintenance and unmade investments in technology and infrastructure will increase needs in 2023 and beyond.

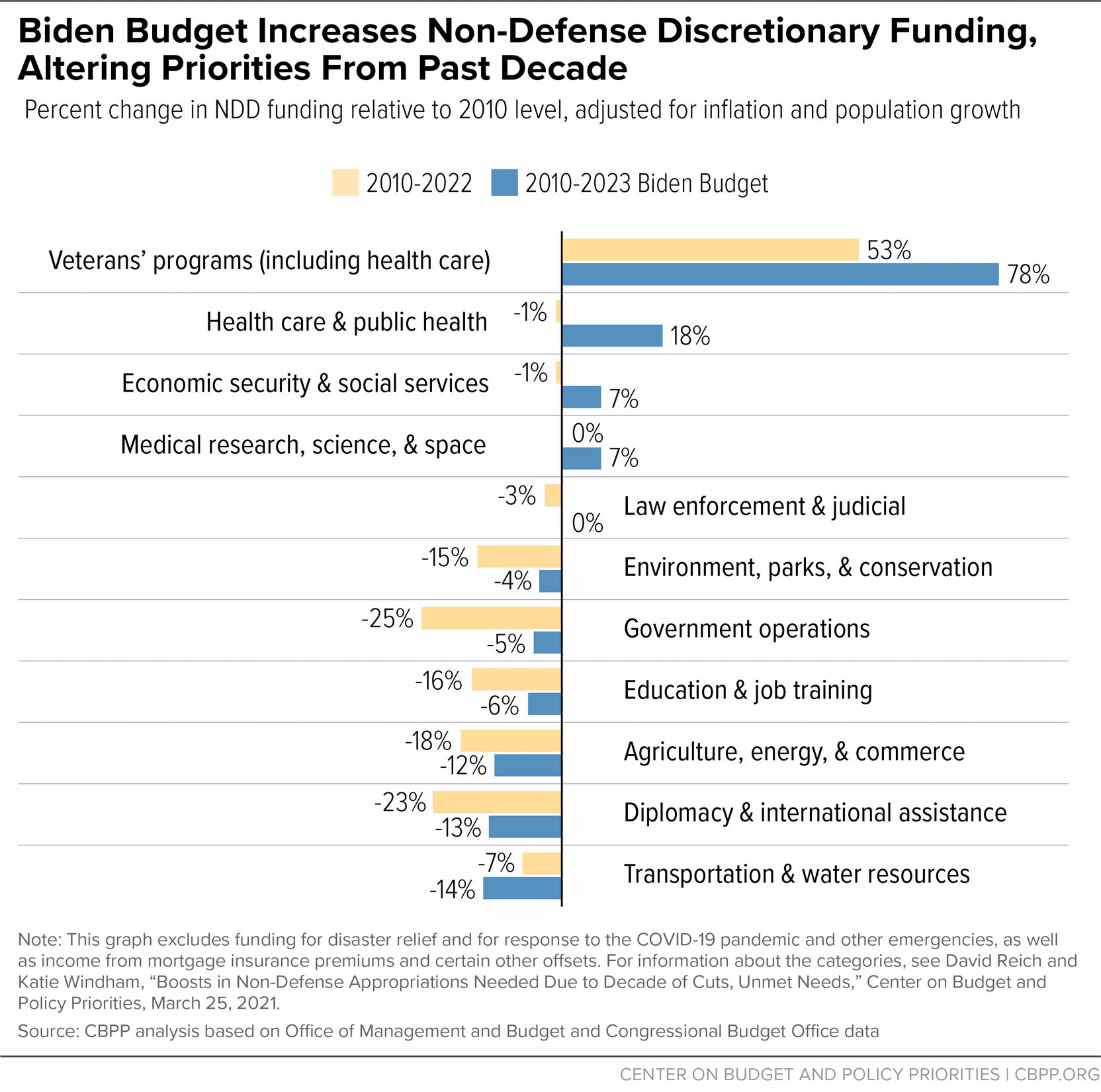

Within the overall appropriations total there is considerable variation, with some agencies and programs ending up with increases relative to their 2010 levels and others remaining below on an inflation- and population-adjusted basis. Figure 4 illustrates this by showing increases and decreases from 2010 by NDD funding categories. The yellow bars show the changes from 2010 to the enacted 2022 levels, while the blue bars show the changes from 2010 to the 2023 Biden budget.

As Figure 4 shows, veterans’ programs (including health care) is the only category to receive a net increase between 2010 and 2022 after adjusting for general inflation and overall population growth.[7] All the other categories were essentially flat or showed substantial decreases, such as the 15 percent cuts for environment, parks, and conservation; the 16 percent cut for education and job training; and the 23 percent cut for diplomacy and international assistance.

Under the 2023 Biden budget, however, several categories go from small cuts to increases relative to their 2010 levels, including an 18 percent increase for health care and public health and 7 percent increases for economic security and social services and for medical research, science, and space. Even with the large overall increase in the budget, several other categories remain below their comparable 2010 levels.

One need is for some funding increases to offset currently rising costs and prices, both economy-wide and in specific sectors like energy. The final inflation rate for 2022 is not yet known and more uncertainty surrounds the course of inflation in 2023, but this should be considered in determining next year’s appropriations.

A broad range of specific needs also should be addressed, many of which are included in the Biden budget. Some involve reversing funding cuts of the past decade that make it harder for agencies to provide basic services or protect health or the environment. Others concern areas such as housing or child care, where federal programs have long met only a fraction of the need. Still others tackle challenges such as climate change. Many of the President’s proposals seek to promote racial equity by strengthening protections against discrimination, fostering opportunity, and assisting people and communities that have been systematically under-resourced. The following are some examples of the needs and priorities addressed in the budget.[8]

Foster Equity in Elementary and Secondary Education. The President’s budget proposes a $2.3 billion (13 percent) increase for the “Title I” Aid to Disadvantaged Students program. The program makes grants to school districts serving communities experiencing high levels of poverty to help them provide additional services and supports to students from low-income or disadvantaged backgrounds. This investment would help narrow the resource gap between high-poverty schools and other schools — a gap that particularly affects students of color.[9] The budget also proposes $16 billion in new mandatory funding for Title I grants to school districts — if enacted, it would roughly double funding for the program relative to its 2022 level.

The budget also calls for a $2.9 billion (22 percent) increase for grants to states under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which helps schools cover the cost of special education services for students with disabilities. Between 2010 and 2022, funding for these grants decreased 12 percent after adjustment for inflation while the estimated number of children receiving special education services increased by 11 percent.[10]

Help People With Low Incomes Afford Housing. Federal rental assistance programs currently help over 5 million low-income households afford safe, stable homes. But due to funding limitations, these programs currently serve only about 1 in 4 eligible households, leaving more than 16 million households at risk of eviction, homelessness, or other forms of housing instability.[11]

The President’s budget proposes to increase funding by $4.8 billion or 17 percent for Housing Choice Vouchers, which help people with low incomes rent modest housing of their choice in the private market. This increase would cover the added cost of families using existing vouchers to stay stably housed in the face of rising rent and utility costs, fund more than 200,000 new vouchers, and provide resources to help expand access to neighborhoods of families’ choosing.[12] The budget also includes new investments to preserve the nation’s public housing developments and improve the quality of life of their residents, and connect people experiencing homelessness with services and housing.

Better Meet Health Care Obligations to American Indians and Alaska Natives. The Indian Health Service (IHS) provides health care to American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIAN), both directly and through programs and facilities operated by tribes and tribal organizations, to fulfill the federal government’s trust responsibilities. AIAN people face considerable health disparities, including life expectancy at birth 5.5 years shorter than the general U.S. population and considerably higher mortality rates from many causes.[13] The IHS (which is part of the Department of Health and Human Services) is chronically underfunded,[14] and the Government Accountability Office has noted that its funding is considerably less, per person served, than the other major federal health care programs.[15] (Unlike veterans’ medical care, Congress has not prioritized ensuring that funding for IHS is sufficient to meet the health care needs of all eligible people.) For 2023, the Biden budget proposes a 38 percent ($2.5 billion) increase for the IHS to reduce funding gaps. Among other things, increases are targeted to improving health care access, modernizing aging facilities and IT infrastructure, and addressing urgent health issues such as HIV, hepatitis C, maternal mortality, and opioid use.

Additionally, tribal nations were especially vulnerable to COVID-19’s health risks and the effects of the recession, due largely to the federal government’s failure to uphold its trust responsibilities and treaty obligations to tribes. The pandemic has also stretched tribal nations’ finances and health systems to the breaking point: AIAN populations had a higher risk of COVID-19 complications; tribal communities faced housing and demographic challenges; and tribal governments faced unique revenue challenges jeopardizing public health funds.

In addition, the Biden Administration proposes to shift IHS funding from annual discretionary appropriations to multi-year mandatory funding to be provided in authorizing legislation, believing that mandatory funding is more likely to be able to provide the substantial increases needed to remedy shortfalls, and provide the stability and predictability needed for effective planning. Until legislation is enacted providing mandatory funding, however, IHS needs will have to be funded within the NDD appropriations totals.

Strengthen Public Health Through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the lack of resources in our nation’s public health systems, such as insufficient staff and inadequate capacities for laboratory analysis, data collection and dissemination, epidemiology, and public communication.[16] While various supplemental appropriations were made to meet emergency COVID-19-related needs, there is also a need to improve regular, ongoing funding for the CDC, which is both the leading federal public health agency and a major source of financial and technical assistance to state and local health departments.

Despite the importance of its mission, the CDC’s regular budget in 2022 is still 8 percent smaller, adjusted only for inflation, than it was 12 years earlier, and 13 percent smaller adjusted for inflation and population growth. (Note that the job of public health departments expands as the population grows, creating more need for services such as immunizations, investigation and monitoring of disease outbreaks, and health education.) The President’s budget proposes a substantial 26 percent ($2.2 billion) increase for the CDC in 2023. Among other uses, it would provide increased support for core public health infrastructure at the federal, state, and local levels; sustain the new Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analysis launched in 2021 with funding through the American Rescue Plan Act; fund infrastructure to improve immunization coverage against a range of vaccine-preventable diseases; and modernize public health data systems.[17]

Increase Financial Aid for College Students. Pell Grants are the foundation of federal financial aid for college students from low- and middle-income families. More than one-third of all undergraduate students receive Pell Grants, which vary in amount according to income and need and are designed to help ensure equal access to postsecondary education. Annual appropriations currently provide more than three-quarters of the funding for this student aid, with mandatory funding supplying the rest.

The purchasing power of Pell Grants has been shrinking. According to the College Board, in academic year 2010-2011 the maximum grant[18] covered 99 percent of average in-state tuition and fees at four-year public universities, but in 2021-2022 it covered only 60 percent of those costs.[19] President Biden’s budget proposes a $1.8 billion increase in Pell Grant appropriations in 2023 to raise the maximum grant by $400. The budget also proposes to double mandatory funding to provide an additional increase of $1,275 in the maximum grant.

Restore IRS Capacity to Enforce Tax Laws and Assist Taxpayers. Funding for the IRS was repeatedly cut over the past decade and is currently 21 percent below its 2010 level after adjusting for inflation, and 26 percent below after adjusting for inflation and population growth. (As the population grows, the IRS needs more auditors and people to provide taxpayer assistance.) These cuts have diminished the agency’s capacity to enforce tax laws and help taxpayers navigate the tax system. Staffing is down by more than one-fifth since 2010. In 2019, the IRS was able to answer fewer than one-third of the taxpayer calls it received. The IRS enforcement division has absorbed some of the largest cuts, with its inflation-adjusted funding falling by 25 percent between 2010 and 2022. The overall audit rate fell by 58 percent between 2010 and 2019, the last year for which comparable data are available, while the audit rates for larger corporations and millionaires fell by 54 percent and 71 percent, respectively.[20] For 2023, the Biden budget proposes a 12 percent increase to begin rebuilding IRS capacity.

Fix Major Shortfalls at the Social Security Administration. As a result of more than a decade of austere operating funding, compounded by the pandemic, the Social Security Administration (SSA) is facing a customer service crisis. Between 2010 and 2022, the SSA’s core operating budget shrank by 17 percent after adjusting for inflation, and its staff was reduced by 13 percent while the number of Social Security beneficiaries increased by 21 percent. Nearly half of calls to SSA go unanswered because callers get busy signals or hang up when the wait is too long. Over 1 million disability claims are pending at state disability determination agencies (which are funded by SSA’s appropriation), with applicants waiting more than six months, on average, for a decision.[21]

The Biden budget requests a $1.3 billion (12 percent) increase in SSA’s basic operating budget in 2023. According to the agency’s projections, that would allow it to maintain roughly the same level of processing times and pending claims as in 2021. SSA’s Commissioner estimates that an increase of $2.3 billion would be needed to improve service.[22]

Another standard way to look at budget levels over time is as percentages of GDP, an approach that puts funding in the context of the economy. Data on this basis are available for appropriated funding back to the mid-1970s and are shown in Figure 5. These long-term data include all classifications of NDD funding, including most emergency funding, because it isn’t feasible to remove from the historical data all appropriations that responded to natural disasters and other emergencies. However, the line in Figure 5 does exclude the large emergency appropriations under the 2009 Recovery Act and for COVID-19 responses and recovery in 2020-2021, as well as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2021(which was designated as an emergency), to better focus on funding for ongoing programs.[23]

Since 1977, NDD funding has averaged 3.5 percent of GDP. Over this period, the percentage has been as high as 5.3 percent and as low as 2.9 percent. Appropriations as a percent of GDP tend to rise during recessions, as policymakers enact more recession-relief spending measures at the same time GDP shrinks. The percentage usually falls as the economy returns to growth and temporary recession-relief spending expires.

NDD funding also tends to rise as a percent of GDP in years with major natural disasters or other emergencies, similarly because policymakers enact measures to respond to them. For example, NDD funding rose sharply from 3.0 percent of GDP in 2017 to 3.6 percent in 2018 largely because of emergency appropriations enacted to address the consequences of hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria.

Over the past decade, NDD funding fell from 3.7 percent of GDP in 2010 to 3.1 percent in 2019. Since then, it has remained in the 3.0 to 3.3 percent range (excluding emergency funding in response to the pandemic and the recession). Even with the increases in the President’s 2023 budget, NDD funding would equal an estimated 3.2 percent of GDP — still below the long-term average of 3.5 percent or the 2010 level of 3.7 percent.

In sum, the austerity of the last decade brought NDD funding to unusually low levels relative to GDP. Reversing that austerity, as the Biden budget proposes, would cause the percentage to rise a bit, but it would remain below the average of the past four-and-a-half decades.

But long-term historical ratios of appropriations to GDP are not necessarily a good indicator of current and future needs, particularly because the U.S. has long lagged behind many other countries in public investments. As a nation gets wealthier, it should be willing to devote more as a share of its economy to boosting educational opportunities, protecting the environment, improving infrastructure, engaging in lifesaving medical research, and ensuring that all children have access to child care. Greater levels of public investment may be needed now to meet current challenges.

Appropriation amounts used in this paper reflect ongoing programmatic funding. They incorporate categories that were exempt from the BCA caps, including funding for overseas contingency operations, program integrity, wildfire suppression, 21st Century Cures Act activities, and the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund. They do not reflect funding designated for disaster relief or emergencies (including various emergency relief measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic or the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act). Disaster and emergency funding is excluded because it is highly variable from year to year, depending on the emergency situations that arise.

In addition, the numbers exclude two large categories of offsets to appropriations: changes to mandatory programs made in appropriations bills (commonly known as “CHIMPs”) and receipts from fees on mortgage insurance programs (FHA and GNMA). Excluding these offsets (but not the funding they offset) better focuses the analysis on actual funding for appropriated programs.

The numbers in this paper continue to reflect funding for the Indian Health Service and Bureau of Indian Affairs in the discretionary appropriations totals, even though President Biden is proposing to shift that funding to the mandatory side of the budget. This treatment is not because of any disagreement with the proposal, but rather is done for comparability with prior years and because those programs will continue to need discretionary appropriations until Congress acts to make the shift. The numbers also exclude funding for the Census Bureau, to avoid distortions from comparing a decennial census year, 2010, with other years when Census appropriations are considerably lower.