State SNAP agencies can play a key role in connecting SNAP participants with much-needed income over the next few months by making sure they do not miss out on the stimulus payments provided by the CARES Act. CBPP estimates that about 12 million low-income Americans, including about 9 million participants in SNAP and/or Medicaid, are at risk of not receiving this payment because they must file a form by November 21 in order to receive it this year, or file a 2020 tax return next year to receive it in 2021. This group includes low-income Americans who don’t file taxes, including very low-income individuals and families with children. For these individuals — many of whom have likely been hit hard by the pandemic’s economic impacts and are having trouble affording basics like food and housing — the stimulus payments can provide a measure of economic relief.

These individuals may not know they are eligible, understand that they must act to receive the payment, or know what steps to take to file for it. State and local SNAP agencies can play a vital role in informing program participants of the availability of the cash payment and connecting them to resources to secure these payments. SNAP agencies have existing communication platforms to share information with SNAP participants, key stakeholders, and the public. In addition, agency leaders have the power to convene key community groups and service providers who are in contact with households likely eligible for these payments. A robust outreach campaign to inform and encourage households to file for their rebate could enable many very poor households to secure these funds who otherwise would miss out. In addition, if federal policymakers issue additional stimulus payments to boost economic demand and reduce hardship, state and local efforts now to connect eligible SNAP participants with the tax system should pay dividends in helping these people access any future rounds of payments.

This is a particularly challenging time for state health and human service agencies. They face unprecedented demand for services from newly eligible households even as social distancing measures severely tax their capacity to manage their workload. States have responded admirably to their residents’ needs: we estimate that some 4 million people were added to SNAP during March and April.[1] And, state health and human services agencies have stepped up their efforts to educate the public about critical, time-sensitive services such as COVID testing, unemployment benefits, and emergency SNAP allotments. While it may be a difficult time for SNAP agencies to consider an additional task, they are extremely well positioned to share needed information with the target population. A robust outreach campaign could bring tens of millions — and as much as hundreds of millions — of dollars in much needed support to many of the state’s poorest individuals. (See the Appendix Table for state-by-state estimates.)

The CARES Act, signed on March 27, includes stimulus payments (technically called Economic Impact Payments or EIPs) to stimulate the economy and help families deal with the fallout from the COVID-19 crisis. The payments — $1,200 per adult ($2,400 for a married couple) and $500 per dependent child — are broad based and available to people with the lowest incomes, including people with zero earnings.[2]

The IRS, working with other agencies, has been automatically delivering EIPs to individuals who are easiest to reach, including those who filed federal income tax returns in 2018 or 2019 and for whom the IRS had direct deposit information, as well as recipients of certain government benefits such as Social Security, Supplemental Security Income, Railroad Retirement, or Veterans Affairs pension or disability benefits. This method, however, misses about 12 million people — adults and children — because they aren’t required to file returns due to their low incomes and they do not participate in one of those specified programs.[3] Together, these 12 million people are eligible to receive $12 billion in payments.

To receive the EIPs this year, these individuals must provide their information to the IRS no later than October 15 through either a 2019 tax return or by November 21 if using the IRS “Non-Filer” tool, a simplified online form for people not required to file a tax return.[4] They can then receive the payment through direct deposit in a bank account or though some payment processing apps or a prepaid debit card; in cases where the IRS does not have direct deposit information, it will mail a paper check or sometimes a prepaid debit card.

By definition, the estimated 12 million people not receiving EIPs automatically have very low incomes because they aren’t required to file federal income tax returns.[5] An estimated 9 million of them receive SNAP or Medicaid, and they qualify for a combined $9 billion in payments.

Low-income individuals have experienced the greatest economic disruptions from this crisis. For example, an Urban Institute analysis found that lower-income families were likelier to lose jobs, hours, or work-related income and likelier to experience hardships such as difficulty paying rent or affording food.[6] Evidence also shows that these problems are compounding existing problems facing low-income people, who are likelier to lack savings because rent and other necessities often eat up their income.[7] For example, since families paying a significant share of their income on rent have little ability to save, losing a job may increase their risk of losing their housing or force them to forgo other basic needs to keep their housing.[8]

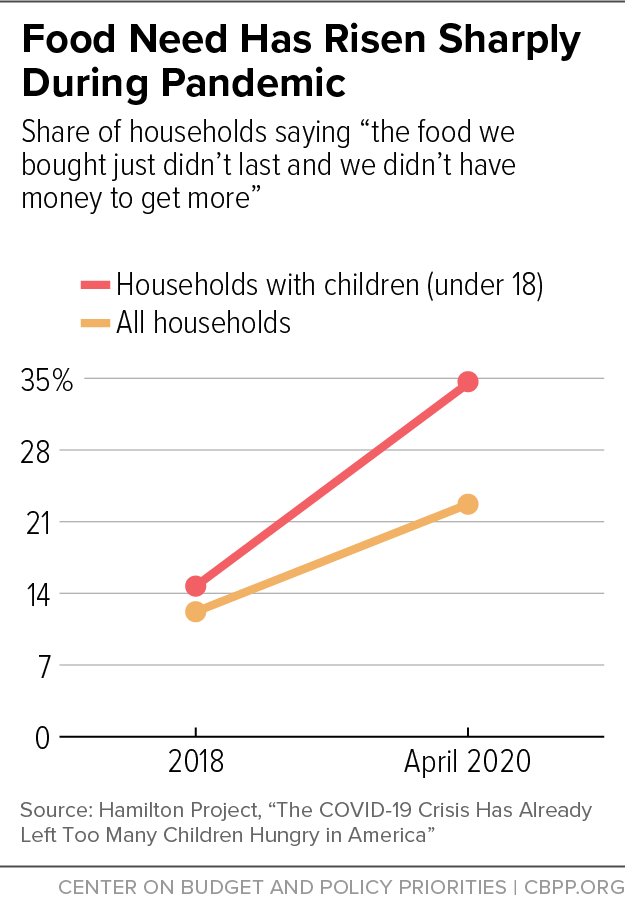

Food insecurity has more than doubled in recent months and risen even more among households with children.[9] (See Figure 1.) Many of these impacts are especially acute for people of color, who are likelier to have low incomes and to experience hardship according to a number of indicators, due to systemic racism and longstanding inequities in wealth and income.[10]

Despite low-income households’ increased hardship, not all have access to government aid, including recent SNAP increases. Evidence shows SNAP benefits already were too low to meet many households’ food needs prior to the pandemic,[11] and the recent temporary benefit enhancements have not reached all who most need them. Emergency SNAP allotments provided by the Families First Coronavirus Recovery Act don’t help the 40 percent of SNAP households with the lowest incomes, including about 16 million households with some 5 million children.[12]

Ensuring that SNAP households can access EIPs will help many vulnerable SNAP participants at risk of hardship. More than one-third of the estimated 9 million SNAP or Medicaid recipients who qualify for the payments but won’t receive them automatically are under age 17. Another 40 percent are either adults without children, including many young adults under age 25 who are at high risk of job loss and unemployment,[13] or older adults (ages 50 to 65) who may face difficulty finding work.

Counties and states that administer SNAP have many unique advantages that they can use to help reach SNAP participants who may risk losing out on the EIPs. SNAP has broad reach among the low-income population, providing benefits to individuals that other programs may not reach. For example, SNAP serves millions of low-income adults without children who may not receive support from any other program, such as those waiting on a disability determination, struggling to find work, or working in jobs with unstable employment.

There are several important ways that state or county SNAP agencies can help SNAP participants or applicants secure their payments, including:

- Informing them of the eligibility criteria and, if possible, helping identify eligible individuals who could be at risk of missing out on payments;

- Providing links to the IRS Non-Filer form and informing them of upcoming deadlines to receive the payment and what documentation they will need to gather beforehand;

- Providing links to other organizations that may provide help in filling out the form, including gathering relevant information, creating an email address, and providing payment information;

- Providing referrals to methods of receiving the payment, including links to payment processing apps or information about setting up an online bank account; and

- Convening other stakeholders, such as service providers and other relevant government agencies, to develop a coordinated campaign.

State and local SNAP agencies have many points of communication with low-income households by which they could share this information. During the application and recertification processes, for example, an individual may: interact with agency staff at an office or through a call center to submit application information, conduct the required interview, or ask questions; visit the website or use a mobile app to submit paperwork or verifications or check on the status of an application; see social media communications; or visit an office to apply and work with staff or submit information through kiosks or computer stations (though most states have temporarily closed offices due to the pandemic). Many agencies also have partnerships with community-based organizations providing SNAP application assistance that could assist with these efforts. And, of course, governors and state agency leadership can help spread the word about the EIPs through traditional media outlets like local TV and newspapers.

State and county health and human services agencies can help connect SNAP participants with this much-needed income through steps such as:

-

Including messaging about EIPs on state websites and mobile apps and in physical offices (when applicable). Almost all state SNAP agencies have websites where they provide basic information about SNAP and how to apply. Some states also enable clients to manage their benefits through online accounts, and many have mobile phone apps with similar functions.[14] States can post information, such as links to the IRS website and the Non-Filer form, on their websites, client account portals, and mobile phone apps. Agencies that use instant messaging or “chatbots” through their websites may be able to include questions and answers about these payments.

In most states, physical offices remain closed for safety reasons due to COVID-19. Ordinarily, some clients can go to an office to apply or perform other tasks, such as providing documentation for verification. Many states have kiosks or computer banks where clients, such as those without internet access, can submit applications or report changes, often with staff available to assist clients. Local offices also post information on waiting room bulletin boards. To the extent feasible in coming months if agencies begin to reopen, state agencies can post information in physical offices or kiosks and equip staff assisting clients in person to provide information.

- Including messaging about EIPs in written client communications. State agencies regularly provide information to clients via email, text message, or regular mail, such as reminders about upcoming appointments, deadlines for recertifications, and information about changes in benefits. They could attach information on EIPs to these communications or send out separate emails or texts if possible. To the extent they use email or text to send important reminders, this may be a powerful way to give clients information about these payments.

- Including messaging about EIPs in phone communications. State agencies routinely communicate with clients by phone and can provide call center employees with scripts to discuss clients’ eligibility for EIPs and assistance with filling out the Non-Filer form. For example, when conducting a phone interview with a client with very low income, a call center employee could be prompted to ask the client if they know about the payments and need help with the process and then provide referrals for interested clients. Agencies could also include recordings about EIPs for call centers’ “on hold” or voicemail messages.

- Providing third-party organizations, such as SNAP application assisters, with messaging about EIPs. Many SNAP agencies work with community-based organizations that assist with outreach and application assistance. These organizations, which have direct contact with many SNAP participants and applicants, may also be able to help individuals complete the Non-Filer form or provide other information. Some may already have relationships with taxpayer assistance groups and Earned Income Tax Credit outreach organizations; for example, a collaboration of groups in Illinois has assembled resources about EIPs and how to file for them at www.getmypaymentil.org. States can boost such efforts by referring SNAP and Medicaid participants to such a site.

- Encouraging local media to write about the EIPs. State agencies often work with local media to share information about key programmatic changes. State leaders could encourage similar coverage on the stimulus payments to educate the public about them, including who needs to file and where local assistance is available.

-

Sharing information through social media channels. At least 48 states have a Twitter or Facebook account to share important program information with clients and key community stakeholders. States could use these social media platforms to educate their followers about the EIPs.

Recently, state agencies have been sharing information about SNAP emergency allotments and how to receive services throughout the COVID-19 crisis. For example, Massachusetts First Lady Lauren Baker and the Red Sox’s Wally the Monster recorded a video for YouTube to inform parents about a new program for school-aged children called Pandemic-EBT.[15] Kansas’ Department for Children and Families hosted a Facebook Live event to take questions from the public about the same program and how to apply.[16] (Such efforts tend to be more successful if structured as campaigns, with multiple posts going out over time to build interest in the topic.) And the Tennessee Department of Human Services encouraged households to apply for its COVID-19 emergency cash assistance by sharing a testimonial video from a woman who had benefited from the program.[17]

State SNAP agencies face many challenges right now, including processing the large increase in applications and adapting procedures for social distancing, but they are uniquely positioned to have a significant impact in enabling clients to access the EIPs, which can provide much-needed assistance to struggling households.

For more information about the payments:

| APPENDIX TABLE |

|---|

| |

Households |

Individuals |

Potential value of payments |

|---|

| |

Total |

Total |

Under 17 years |

In millions of dollars |

|---|

| United States |

3,270,000 |

6,534,000 |

3,024,000 |

$5,700 |

| Alabama |

45,500 |

99,600 |

47,700 |

$86 |

| Alaska |

7,900 |

17,700 |

7,700 |

$16 |

| Arizona |

68,500 |

133,000 |

56,300 |

$120 |

| Arkansas |

20,800 |

46,800 |

23,500 |

$40 |

| California |

543,600 |

1,095,100 |

548,900 |

$930 |

| Colorado |

35,200 |

78,700 |

42,200 |

$65 |

| Connecticut |

39,100 |

65,400 |

22,800 |

$63 |

| Delaware |

11,300 |

22,800 |

11,100 |

$20 |

| District of Columbia |

13,200 |

23,500 |

9,300 |

$22 |

| Florida |

245,800 |

437,400 |

184,000 |

$396 |

| Georgia |

151,800 |

330,400 |

158,500 |

$286 |

| Hawaii |

12,100 |

22,800 |

9,500 |

$21 |

| Idaho |

7,300 |

18,800 |

10,800 |

$15 |

| Illinois |

172,000 |

315,900 |

129,200 |

$289 |

| Indiana |

34,600 |

79,200 |

39,900 |

$67 |

| Iowa |

26,300 |

55,600 |

27,900 |

$47 |

| Kansas |

9,100 |

21,600 |

11,800 |

$18 |

| Kentucky |

49,700 |

95,900 |

36,400 |

$90 |

| Louisiana |

48,300 |

113,300 |

60,400 |

$94 |

| Maine |

6,900 |

14,900 |

6,900 |

$13 |

| Maryland |

67,300 |

121,800 |

50,000 |

$111 |

| Massachusetts |

56,100 |

108,200 |

48,200 |

$96 |

| Michigan |

93,500 |

159,100 |

53,100 |

$154 |

| Minnesota |

26,100 |

49,500 |

27,100 |

$40 |

| Mississippi |

41,600 |

88,800 |

40,800 |

$78 |

| Missouri |

38,400 |

86,300 |

45,700 |

$72 |

| Montana |

5,100 |

11,600 |

5,400 |

$10 |

| Nebraska |

9,600 |

20,900 |

11,000 |

$17 |

| Nevada |

38,300 |

69,700 |

28,400 |

$64 |

| New Hampshire |

4,400 |

9,900 |

4,900 |

$8 |

| New Jersey |

66,800 |

139,800 |

76,800 |

$114 |

| New Mexico |

27,000 |

56,800 |

25,200 |

$51 |

| New York |

188,600 |

351,200 |

152,500 |

$315 |

| North Carolina |

120,900 |

241,400 |

110,200 |

$213 |

| North Dakota |

3,400 |

8,400 |

4,400 |

$7 |

| Ohio |

92,900 |

179,800 |

78,100 |

$161 |

| Oklahoma |

31,100 |

74,000 |

38,200 |

$62 |

| Oregon |

50,600 |

92,700 |

34,400 |

$87 |

| Pennsylvania |

105,500 |

211,700 |

95,200 |

$187 |

| Rhode Island |

11,200 |

19,900 |

7,700 |

$18 |

| South Carolina |

58,500 |

134,200 |

68,900 |

$113 |

| South Dakota |

5,500 |

13,900 |

7,600 |

$11 |

| Tennessee |

80,700 |

161,400 |

70,100 |

$145 |

| Texas |

290,500 |

610,000 |

300,700 |

$521 |

| Utah |

13,900 |

33,200 |

18,600 |

$27 |

| Vermont |

2,500 |

5,100 |

2,300 |

$4 |

| Virginia |

53,000 |

126,000 |

65,700 |

$105 |

| Washington |

68,900 |

118,800 |

47,100 |

$110 |

| West Virginia |

25,100 |

50,800 |

20,600 |

$47 |

| Wisconsin |

34,800 |

67,800 |

28,500 |

$61 |

| Wyoming |

1,800 |

4,700 |

2,500 |

$4 |