The new House Republican poverty plan unveiled on June 7 appears to propose rigid work requirements for participants in the three largest federal rental assistance programs: Housing Choice Vouchers, Project-Based Rental Assistance, and public housing. The great majority of rental assistance recipients are elderly, have disabilities, or already work, but raising employment and earnings so that more recipients can potentially escape poverty is nonetheless a very important goal. The work requirements in the House Republican plan, however, are unlikely to make significant progress toward this goal.

Research shows that rigid work requirements don’t lead to stable employment on a widespread basis or lift families out of poverty, and that they often push families — especially those with mental or physical health limitations or other barriers to employment — deeper into poverty because the families can end up with neither employment nor assistance. The House Republican proposal would be particularly likely to produce disappointing results because it provides no added resources for job training, subsidized job slots, child care assistance, or other work supports to help rental assistance recipients prepare for work or raise their earnings. State agencies administering the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program — which under the House GOP plan would operate the work programs for rental assistance recipients — are unlikely to be able to provide the needed training, work supports, or the like using existing resources. Nor, in all likelihood, could rental assistance administrators, whose resources would be stretched just to cover the basic costs of administering or enforcing work requirements.

Moreover, the requirements would conflict with rental assistance programs’ basic goal of providing decent, stable housing in a broad range of neighborhoods. They could expose children and others whose households lose rental assistance to housing instability and even homelessness. They also would discourage private owners from renting to voucher holders by undercutting a major attraction of doing so: the fact that vouchers now provide regular monthly rental payments even if a tenant becomes unemployed or otherwise loses income. And they could restrict important uses of rental assistance that reduce public costs in other programs but help some people who are not currently working, such as providing vouchers to families at risk of losing their children to child welfare placements because they cannot afford adequate housing.

In addition, the proposed work requirements are not needed. Research — particularly the Jobs Plus demonstration — indicates that voluntary work programs can substantially increase employment and earnings among rental assistance recipients.

Imposing work requirements would be especially unwise now, because Congress recently directed the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to undertake a major effort to evaluate alternative rental assistance policies, including policies designed to support work. These evaluations, which will be conducted as part of a major expansion of HUD’s Moving to Work demonstration that Congress enacted in late 2015, should generate substantial new information on what policies work best to boost employment and earnings among rental assistance recipients.

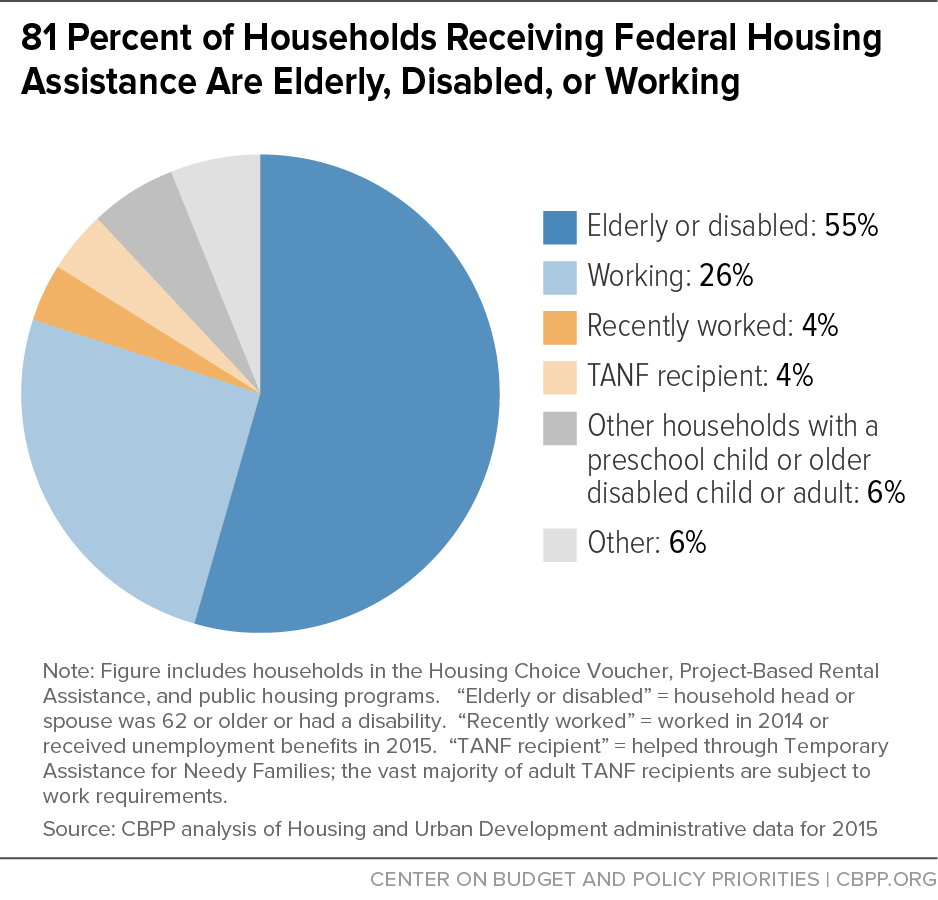

The three housing programs that the House Republican proposal covers help about 4.5 million low-income households afford decent, stable housing.[1] Fully 81 percent of those households in 2015 were either elderly or disabled[2] or included a member who worked (see Figure 1). Another 4 percent of these households included a member who had recently worked,[3] and a further 4 percent were likely already subject to work requirements under TANF. Of the remaining households, close to half included a preschool child or an older child or adult with a disability; it may be difficult for adults in these households to work without assistance to help care for these individuals.

Thus, only about 261,000 households receiving rental assistance in 2015 — 6 percent of the total — included adults who apparently could work but had not worked recently and were not already subject to work requirements or potentially prevented from working by caretaking responsibilities.[4]

Nonetheless, helping the minority of rental assistance recipients who can work but do not to prepare for and find jobs is an important policy goal, as is enabling working recipients to increase their earnings. The evidence suggests, however, that work requirements are not needed to achieve these goals and that rigid requirements like those proposed by House Republicans could harm low-income families and undercut the effectiveness of rental assistance programs.

Little evidence exists on the effects of work requirements in rental assistance programs.[5] Research on cash assistance programs, however, indicates that TANF-style work requirements like those the House Republican plan proposes for rental assistance generated only modest increases in employment rates initially and that these increases faded over time. Few participants obtained stable employment or raised their incomes above the poverty line. Moreover, most participants facing significant barriers to employment (such as physical or mental health limitations) never found work, and the requirements left some recipients and their children worse off because they wound up with neither earnings nor cash assistance and consequently fell deeper into poverty.[6]

Research also suggests that voluntary programs — such as the Jobs-Plus demonstration, which policymakers expanded in fiscal years 2015 and 2016 and President Obama proposed to expand further in his 2017 budget — can improve employment rates and incomes for recipients of rental assistance without the risk of hardship and other adverse effects from work requirements. A rigorous evaluation of Jobs-Plus, which offers employment services, peer guidance, and financial incentives to public housing residents, found that participants achieved a 16 percent increase in earnings over a seven-year period relative to residents of nearby public housing developments that did not implement Jobs-Plus.[7]

The House Republican work requirement proposal is particularly unlikely to succeed in raising families out of poverty because it does not provide resources for child care assistance, education and training programs, subsidized employment slots, or other work supports to help families build their skills, become employed, and increase their earnings. It acknowledges that families need a range of supports, stating that non-working, work-capable rental assistance recipients would meet with “TANF case workers who collaborate with them to develop self-sufficiency plans and assist in making arrangements to prepare for work, such as child care, transportation, work clothes, and other necessities to transition to regular employment.”[8] And it rightly recognizes that entities experienced in administering work programs should play a central role in providing employment services to rental assistance recipients, rather than housing agencies that administer public housing and vouchers, which typically have little expertise in this area. (The third program covered by the proposal, Project-Based Rental Assistance, is administered by owners of housing developments who receive subsidies directly from HUD in return for providing affordable housing. These owners are largely for-profit entities with no capacity to administer work programs.)

It is unlikely, however, that TANF agencies would be able or willing to administer effective work programs for rental assistance recipients. First, few TANF resources are devoted to work or work preparation programs even for people who are TANF recipients; only 8 percent of TANF resources are used for this purpose, and as a result, TANF recipients typically receive only shallow services insufficient to enable people with major employment barriers to secure a toehold in the labor market. The House GOP plan fails to explain how state TANF agencies would somehow serve large numbers of rental assistance recipients as well — only 8 percent of rental assistance recipients also are TANF recipients,[9] so the proposal would substantially increase TANF agencies’ workload — without substantial additional resources. The plan does not call for any increase in TANF funding, and it’s improbable states would provide the needed funds from their existing funding.

Moreover, the plan also doesn’t call for any additional funding for child care, and states currently serve only one of every six eligible low-income children in their subsidized child care programs. (Many states have opted to shift TANF funds to other parts of their budgets rather than to support work activities, child care, or cash assistance for TANF participants, and they are unlikely to shift those funds back to aid rental assistance recipients.)[10]

Finally, there is no recent evidence indicating whether state TANF programs are even effective in raising employment or reducing poverty, since states are not held accountable for these outcomes or even required to collect data needed to assess their performance.[11]

Nor do rental assistance administrators have the resources to provide adequate case management and supportive services. The main funding streams potentially available for these purposes, public housing operating subsidies and voucher administrative fees, have been deeply underfunded for years. In 2016, for example, agencies are receiving 90 percent of the operating subsidies and 84 percent of the voucher administrative fees for which they are eligible because Congress did not appropriate enough money to cover the full amounts they are due.

Housing agencies would have difficulty stretching those resources even to cover the basic costs of monitoring and enforcing work requirements. Recipients are scattered over nearly 4,000 state and local housing agencies and a much larger number of project-based rental assistance owners. For example, 3,200 housing agencies assist at least one of the 261,000 rental assistance households noted above in which an adult apparently could work but has not worked recently and isn’t already likely subject to work requirements under TANF (or potentially prevented from working by caretaking responsibilities).

The House Republican plan includes vague language calling for greater state flexibility in using federal resources, and this flexibility could potentially include permitting states to shift federal funds from housing subsidies to work supports. But if that is the plan’s intention, it would directly reduce the number of low-income families with basic rental assistance and thus be even more likely to increase homelessness and housing instability than the work requirements themselves.

If work requirements result in the loss of rental assistance for substantial numbers of families where parents are not employed — as the experience with TANF-style work requirements suggests is likely — the effects on children in those families could be harsh and enduring. Research comparing families with children who were randomly assigned to receive housing vouchers to a control group of families that did not receive them shows that the latter group of children was substantially more likely to experience homelessness or housing instability or to live in overcrowded or lower-quality housing.[12] These problems have been linked in other studies to long-term harm to children’s health and development.[13]

Children in families without vouchers were also more likely to be placed in foster care, which can result from parents’ inability to afford suitable housing, or compelled to change schools, which has been shown to disrupt academic progress. Those families also experienced higher rates of alcohol dependence, psychological distress, and domestic violence victimization.[14]

Families terminated from rental assistance due to work requirements would be replaced by other families from waiting lists. But even if the number of families assisted at a given time stayed the same, abruptly cutting off assistance for a family before it can afford housing on its own and issuing assistance to another family would likely reduce the effectiveness of federal rental assistance overall. This is because enabling families to obtain stable housing produces some of the most powerful benefits of rental assistance, such as enabling a child to stay in the same school instead of bouncing from one to another.

A growing body of research shows that rental assistance can substantially reduce public costs in other program areas under some circumstances. For example, one study found that rental assistance combined with supportive services for families at risk of losing their children to child welfare placements produced savings in the child welfare and emergency shelter systems that offset almost the entire cost of the rental assistance and supportive services over the two-year study period.[15] Similarly, vouchers provided to homeless families with children reduced other shelter costs (such as those for transitional housing and emergency shelter) enough to offset nearly the entire cost of the vouchers over the 18-month period covered by another study.[16] In addition, rental assistance combined with supportive services for homeless individuals with serious health problems has been shown to produce major savings in the health care, corrections, and emergency shelter systems.[17]

The House GOP report recommends enhancing the “portability” of housing vouchers to enable more families with vouchers to move to areas with more jobs, better schools, and other opportunities. To help accomplish this goal, the report urges reform of the fragmented administration of the voucher program by public housing agencies, and permitting non-profits “and other cost-effective service providers” to administer vouchers.

CBPP has written extensively about the importance of these and other strategies to realize the Housing Choice Voucher program’s potential to enable families to move to neighborhoods with greater opportunities.a In addition to the policy changes HUD can make to encourage agencies to help more families use vouchers in higher opportunity areas, Congress could help to achieve these goals.

In the near term, the House could make three changes in its fiscal year 2017 funding bill for HUD:

- include the $15 million the Administration requested for a Housing Choice Voucher Mobility Demonstrationb (the Senate bill includes $14 million for this purpose);

- give HUD the flexibility to use funds to pay for the costs of administering vouchers across jurisdictional lines and to reward agencies that increase families’ access to higher opportunity areas; and

- provide additional housing voucher administrative funds (which are flat-funded in the House committee bill but increased $119 million in the Senate bill).

a Barbara Sard and Douglas Rice, “Realizing the Housing Voucher Program’s Potential to Enable Families to Move to Better Neighborhoods,” January 12, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/realizing-the-housing-voucher-programs-potential-to-enable-families-to-move-to; Barbara Sard and Deborah Thrope, “Consolidating Rental Assistance Administration Would Increase Efficiency and Expand Opportunity,” April 11, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/consolidating-rental-assistance-administration-would-increase-efficiency-and-expand.

b Barbara Sard, “Modest Investment in Housing Mobility Could Yield Big Benefits,” March 15, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/modest-investment-in-housing-mobility-could-yield-big-benefits.

These findings stem from initiatives targeting some of the most vulnerable rental assistance recipients, including many that were not working at the time. Initiatives like these would probably not produce the same outcomes if work requirements cut off assistance to individuals and families that were not employed, since those individuals and families are likely to face the greatest risk of problems like homelessness and child welfare placements and therefore to generate a large share of the savings from reducing those problems. As a result, work requirements could curtail some of the most cost-effective and beneficial uses of rental assistance.

Families generally use housing vouchers to rent modest units of their choice in the private market. In most cases, owners are not required to accept the vouchers, so the program relies on owners’ voluntary participation. Work requirements could deter private owners from renting to voucher holders, especially in low-poverty neighborhoods where vouchers most effectively help families escape the cycle of poverty.

To participate in the voucher program, owners must comply with certain administrative requirements, such as allowing housing quality inspections to ensure that voucher holders do not live in substandard housing. Owners rent to voucher holders despite those requirements mainly because the voucher ensures a steady stream of rental payments, even if a tenant becomes unemployed and cannot immediately find a new job, or otherwise loses income. A work requirement that could cut off assistance to some families when they are least able to afford the rent themselves would undercut this benefit, likely reducing the number of owners who accept vouchers.

This risk would be strongest in low-poverty neighborhoods with low crime and strong schools, where competition for units from families with higher incomes is often intense. Reducing access to these neighborhoods would be particularly harmful. Rigorous research shows that when families with young children use vouchers to move to low-poverty neighborhoods, those children earn 30 percent more on average as adults and are much more likely to attend college and less likely to become single parents.[18]

In December 2015, policymakers enacted a major expansion of HUD’s Moving to Work (MTW) demonstration, more than tripling the number of agencies permitted to participate. MTW’s broad waivers of federal laws and regulations allow participating agencies to test alternative policies, including work requirements and other policies intended to support employment. But MTW, first implemented in 1998, has produced few findings about what policies are effective because it has not been rigorously evaluated and agencies can make so many changes simultaneously that it’s hard to assess the impact of any one.

Recent legislation expanding MTW sought to address these shortcomings by directing HUD to conduct a rigorous evaluation in consultation with an expert advisory committee and to require each group of new MTW agencies to test a specific alternative policy. This expansion offers an opportunity to learn what policies are most effective in raising earnings and employment for families and protecting them from hardship. It would be premature — and contrary to the House Republican proposal’s stated emphasis on evidence-based policy — to implement work requirements nationally just as this expansion is getting underway and before it produces evaluation results.

Until additional research findings are available, it would be a sounder approach to expand the Jobs-Plus program to additional housing agencies, as the Administration’s 2017 budget proposes. As noted above, Jobs-Plus — which provides employment services, financial incentives, and peer guidance, but not work requirements — is backed by rigorous evidence showing that it raises earnings among public housing residents.