End Notes

[1] We are grateful to The Kresge Foundation and the Melville Charitable Trust for their support of this paper.

[2] There are a number of well-designed experimental and quasi-experimental studies, as well as a large body of case studies for these groups. For reviews, see Carol L.M. Caton, Carol Wilkins, and Jacquelyn Andersen, “People Who Experience Long-Term Homelessness,” chapter 4 in Deborah Dennis, Gretchen Locke, and Jill Khadduri, eds., Toward Understanding Homelessness: The 2007 National Symposium on Homelessness Research, Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, September 2007, https://aspe.hhs.gov/execsum/toward-understanding-homelessness-2007-national-symposium-homelessness-research; Thomas Byrne et al., “The Relationship between Community Investment in Permanent Supportive Housing and Chronic Homelessness,” Social Service Review, June 2014, Vol. 88, No. 2, pp. 234-263; Debra Rog et al., “Permanent Supportive Housing: Assessing the Evidence,” Psychiatric Services, March 2014, Vol. 65, No. 3, pp. 287-294.

[3] “No Strings Attached: Helping Vulnerable Youth with Non-Time-Limited Supportive Housing” CSH, March 2016, http://www.csh.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/CSH_NonTimeLimitedYouthSH_3.25.16.pdf.

[4] Frank R. Lipton et al. “Tenure in Supportive Housing for Homeless Persons with Severe Mental Illness,” Psychiatric Services, April 2000, Vol. 51, No. 4, pp 479-486.; Sam Tsemberis and Ronda Eisenberg, “Pathways to Housing: Supported Housing for Street-Dwelling Homeless Individuals with Psychiatric Disabilities,” Psychiatric Services, April 2000, Vol. 51, No. 4, pp. 487-493.

[5] Robert Rosenheck et al., “Cost-Effectiveness of Supported Housing for Homeless Persons with Mental Illness,” Archives of General Psychiatry, September 2003, Vol. 60, No. 9, pp. 940-951.

[6] Stephen H. Leff et al., “Does One Size Fit All? What We Can and Can’t Learn from a Meta-Analysis of Housing Models for Persons with Mental Illness,” Psychiatric Services, April 2009, Vol. 60, No. 4, pp. 473-482.

[7] Laura S. Sadowski et al., “Effect of a Housing and Case Management Program on Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalizations Among Chronically Ill Homeless Adults,” Journal of the American Medical Association, May 2009, Vol. 301, No. 17, pp. 1771-1778.

[8] Dennis P. Culhane, Stephen Metraux, and Trevor Hadley, “Public Service Reductions Associated with Placement of Homeless Persons with Severe Mental Illness in Supportive Housing,” Housing Policy Debate, 2002, Vol. 13, Issue 1, pp. 107-163.

[9] Metraux and Culhane (2004) found that 45 percent of those leaving jails or prisons with a prior history of homeless shelter use reentered shelters, mostly within the first month of release. People who had contact with the mental health system had more shelter stays and re-incarcerations than those who had not. Similarly, Culhane, Metraux, and Hadley (2002) found that, among people experiencing homelessness entering supportive housing in New York City, 26 percent had stayed in a state run psychiatric hospital in the two years prior to moving into supportive housing. Hopper et al. (1997) conducted in-depth interviews with 36 people experiencing homelessness. They identified a sub-set of these individuals who lived in an “institutional circuit” — they spent some time homeless, but they spent about 40 percent of their time cycling between hospitals, psychiatric institutions, and prisons and jails.

Stephen Metraux and Dennis Culhane, “Homeless Shelter Use and Reincarceration Following Prison Release,” Criminology and Public Policy, 2004, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 139-160; Culhane, Metraux, and Hadley, 2002; Kim Hopper et al., “Homelessness, Severe Mental Illness, and the Institutional Circuit,” Psychiatric Services, May 1997, Vol. 48, No. 5, pp. 659-664.

[10] Culhane, Metraux, and Hadley, 2002.

[11] Studies include between 25 and 80 people.

[12] Leyla Gulcur et al., “Housing, Hospitalization, and Cost Outcomes for Homeless Individuals with Psychiatric Disabilities Participating in Continuum of Care and Housing First Programmes,” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, April 2003, Vol. 13, pp. 171-186.

[13] Jocelyn Fontaine et al., “Supportive Housing for Returning Prisoners: Outcomes and Impacts of the Returning Home Ohio Pilot Project,” Urban Institute, August 2012, http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/412632-Supportive-Housing-for-Returning-Prisoners-Outcomes-and-Impacts-of-the-Returning-Home-Ohio-Pilot-Project.PDF.

[14] Rosenheck et al., 2003.

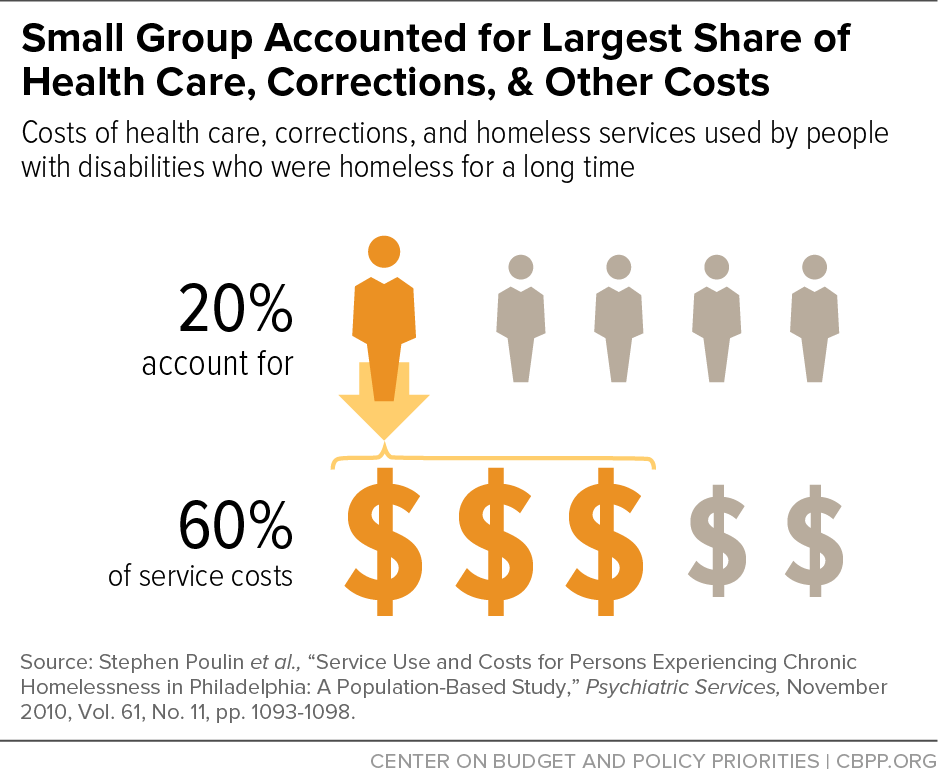

[15] Stephen Poulin et al., “Service Use and Costs for Persons Experiencing Chronic Homelessness in Philadelphia: A Population-Based Study,” Psychiatric Services, November 2010, Vol. 61, No. 11, pp. 1093-1098.

[16] High-need participants were identified using screening tools that indicate low ability to function in the community and high mental health needs, and they had to have a history of hospitalization due to mental illness, co-occurring substance use disorder, or a recent arrest or incarceration. Moderate-need participants included everyone who didn’t fit into the high-need category. See http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/1/2/e000323.full.pdf+html for more information.

[17] Paula Goering et al., “National At Home/Chez Soi Final Report,” Calgary, AB: Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2014, http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca.

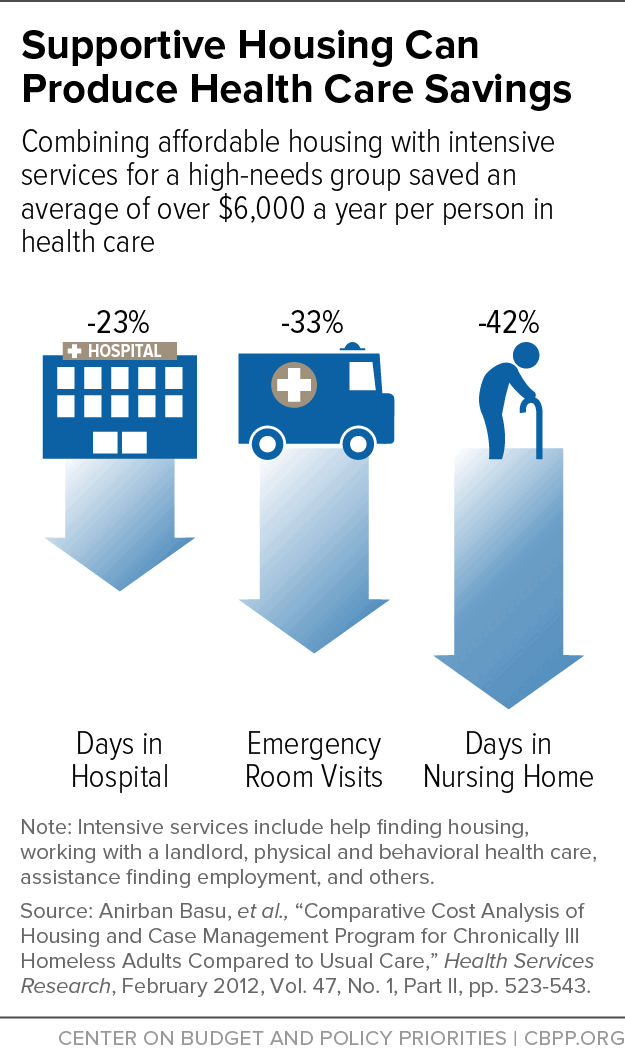

[18] Anirban Basu et al., “Comparative Cost Analysis of Housing and Case Management Program for Chronically Ill Homeless Adults Compared to Usual Care,” Health Services Research, February 2012, Vol. 47, No. 1, Part II, pp. 523-543.

[19] These reductions are reported as annualized averages. The researchers averaged the intervention group’s changes in health care utilization during the 18-month study period and adjusted the utilization to be equivalent to health care use in one year.

[20] David Buchanan et al., “The Health Impact of Supportive Housing for HIV-Positive Homeless Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” American Journal of Public Health, November 2009, Vol. 99, No. S3, pp. 675-680.

[21] The researchers define “intact immunity” as having a CD4 count above 200 and viral load below 100,000.

[22] Sandra K. Schwarz et al., “Impact of Housing on the Survival of Persons with AIDs,” BMC Public Health, July 2009, http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-9-220.

[23] Debra Rog et al., 2014; Martha Burt, Carol Wilkins, and Danna Mauch, “Medicaid and Permanent Supportive Housing for Chronically Homeless Individuals: Literature Synthesis and Environmental Scan,” Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, January 6, 2011, https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/medicaid-and-permanent-supportive-housing-chronically-homeless-literature-synthesis-and-environmental-scan.

[24] Sam Tsemberis, Leyla Gulcur, and Maria Nakae, “Housing First, Consumer Choice, and Harm Reduction for Homeless Individuals With a Dual Diagnosis,” American Journal of Public Health, April 2004, Vol. 94, No. 4, pp. 651-656.

[25] An-Lin Cheng et al., “Impact of Supported Housing on Clinical Outcomes Analysis of a Randomized Trial Using Multiple Imputation Technique,” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, January 2007, Vol. 195, No. 1, pp. 83-88.

[26] The original analysis of the data found no difference in alcohol or drug use between those with and without supportive housing, but a substantial amount of the data for the non-supportive housing groups was missing. A subsequent analysis that adjusted for the missing data found large reductions in alcohol and drug use.

[27] Martha Burt, Carol Wilkins, and Danna Mauch, 2011.

A study of the Downtown Emergency Services Center’s 1811 Eastlake property found that even people with severe alcohol problems reduced their alcohol use in supportive housing. See Mary E. Larimer et al., “Health Care and Public Service Use and Costs Before and After Provision of Housing for Chronically Homeless Persons with Severe Alcohol Problems,” JAMA, (2009), Vol. 301, No. 13, pp. 1349-1357.

[28] Caton, Wilkins, and Andersen, 2007.

[29] Sune Rubak et al., “Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” British Journal of General Practice, April 2005, Vol. 55, No. 513, pp. 305–312, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1463134/.

[30] In 2014, over 7 percent of people in supportive housing for the homeless were 62 or older, and that number will likely grow as the population ages. See “The 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress, Part 2: Estimates of Homelessness in the United States,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development, https://www.hudexchange.info/resource/4828/2014-ahar-part-2-estimates-of-homelessness/.

[31] Nicholas Castle and Neil Resnick, “Service-Enriched Housing: The Staying at Home Program,” Journal of Applied Gerontology, July 2014, pp. 1-21.

[32] Seniors did not differ in demographics or functional status across the intervention and control groups.

[33] Arkadipta Ghosh, Cara Orfield, and Robert Schmitz, “Evaluating PACE: A Review of the Literature,” prepared for the Office of Disability, Aging, and Long-Term Care Policy, and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, January 2014, https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/evaluating-pace-review-literature; Ruth Elkan, et al., “Effectiveness of Home-based Support for Older People: Systematic Review and Metaanalysis,” BMJ, September 2001, Vol. 323, No. 7315, pp. 719-725.

[34] “The Minnesota Supportive Housing and Managed Care Pilot: Evaluation Summary,” prepared for Heart Connection by the National Center on Family Homelessness, March 2009, http://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Evaluation-Minnesota-Supportive-Housing-and-Managed-Care-Pilot-2009.pdf.

[35] Debra J. Rog and John C. Buckner, “Homeless Families with Children,” Chapter 5 in Toward Understanding Homelessness: The 2007 National Symposium on Homelessness Research, eds. Deborah Dennis, Gretchen Locke, and Jill Khadduri, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Housing and Urban Development, September 2007, https://aspe.hhs.gov/legacy-page/2007-national-symposium-homelessness-research-homeless-families-and-children-146546.

[36] Daniel Gubits et al., “Family Options Study: Short-Term Impacts of Housing and Services Interventions for Homeless Families,” Office of Policy Development and Research, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, July 2015, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/family_options_study.html.

[37] Anthony L. Loman, “Families Frequently Encountered by Child Protection Services: A Report on Chronic Child Abuse and Neglect,” Institute of Applied Research, February 2006, http://www.iarstl.org/papers/FEfamiliesChronicCAN.pdf.

[38] Rebecca Swann-Jackson, Donna Tapper, and Allison Fields, “Keeping Families Together: An Evaluation of the Implementation and Outcomes of a Pilot Supportive Housing Model for Families Involved in the Child Welfare System,” Metis Associates, November 2010, http://www.csh.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Report_KFTFindingsreport.pdf.

[39] Mary Cunningham et al., “Supportive Housing for High-Need Families in the Child Welfare System,” Urban Institute, November 2014, http://www.urban.org/research/publication/supportive-housing-high-need-families-child-welfare-system.

[40] Over 96,000 people were classified as chronically homeless (a small subset of the total homeless population which usually need supportive housing), including more than 13,000 people in families with children, on one night in January 2015. About 95,000 beds in supportive housing were dedicated to this group that year. People are classified as chronically homeless if they have disabilities and have experienced at least 12 months of homelessness, either continuously or cumulatively over three years.

There are another 224,146 beds in supportive housing for people with disabilities who are homeless but not chronically. Some 488,000 adults spent at least one night in a homeless shelter during 2014 and had a disability, but not all these adults would need supportive housing. In total, 1.488 million people spent at least one night in a shelter in 2014. Likely some small portion of this total also need supportive housing but were not identified as having a disability.

There are at least hundreds of thousands of additional people who live in in nursing homes, psychiatric institutions, jails, and prisons and could move into the community with supportive housing, but the exact number who need supportive housing (as opposed to affordable housing with less intensive services) is unknown. Supportive housing does exist for these groups, but there are no accurate counts of the number of units.

“The 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, Part 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness.” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Community Planning and Development, November 2015, https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2015-AHAR-Part-1.pdf; “The 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, Part 2: Estimates of Homelessness in the United States,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Community Planning and Development, November 2015, https://www.hudexchange.info/onecpd/assets/File/2014-AHAR-Part-2.pdf.

[41] See Part VI of Barbara Sard and Will Fischer, “Chart Book: Federal Housing Spending Is Poorly Matched to Need,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 18, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/chart-book-federal-housing-spending-is-poorly-matched-to-need.

[42] Policymakers have funded about 80,000 Housing Choice Vouchers for homeless veterans with disabilities, called Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing vouchers (or HUD-VASH), since 2008. Veteran homelessness declined 36 percent between 2010 and 2015.

[43] The three largest rental assistance programs are Housing Choice Vouchers, Public Housing, and Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA). Policymakers ceased the expansion of Public Housing and PBRA in the mid-1990s. For more information see the Center’s Policy Basics on Housing Choice Voucher, Public Housing, and Project-Based Rental Assistance programs: https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/policy-basics-the-housing-choice-voucher-program; https://www.cbpp.org/research/policy-basics-introduction-to-public-housing; and https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/policy-basics-section-8-project-based-rental-assistance.

[44] Public housing agencies dedicate project-based vouchers to specific units by contract, for an initial term of up to 15 years. For more information see the Center’s Policy Basics: Project-Based Vouchers.

[45] “The 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, Part 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Community Planning and Development, November 2015, https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2015-AHAR-Part-1.pdf.

[46] Rachel Bergquist et al., “State Funded Housing Assistance Programs,” Technical Assistance Collaborative, April 2014, http://www.tacinc.org/media/43566/State%20Funded%20Housing%20Assistance%20Report.pdf.

[47] Less than a quarter of PHAs target some of their Public Housing or Housing Choice Vouchers toward homelessness or reduce screening barriers for homeless households. See “Study of PHAs’ Efforts to Serve People Experiencing Homelessness,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/pdf/pha_homelessness.pdf.

[48] Investors fund part of the cost of supportive housing development by purchasing credits that states allocate to particular developments; in exchange, the credits reduce their federal tax liability.

[49] See the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s “National Housing Trust Fund Resources” page, http://nlihc.org/issues/nhtf/resources, for more information.

[50] This was done using a Medicaid 1115 waiver, which can be used for demonstration projects meant to test new service delivery and payment models. These waivers must be budget neutral for the federal government and include an evaluation component. States can use these waivers to test adding new benefits to their Medicaid program and directing those services to a particular subset of their Medicaid-eligible beneficiaries. California’s new waiver was approved in December 2015.

[51] See the Supportive Housing Network of New York’s “Medicaid Redesign” page, http://shnny.org/budget-policy/state/medicaid-redesign/, for more information on New York’s supportive housing plan.

[52] Vikki Wachino, “Coverage of Housing-Related Activities and Services for Individuals with Disabilities,” Center for Medicaid & CHIP Services, June 26, 2015, https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib-06-26-2015.pdf.

[53] See CSH’s “A Quick Guide to Improving Medicaid Coverage for Supportive Housing Services” for detailed information about various Medicaid waivers and state plan options, http://www.csh.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/A-Quick-Guide-To-Improving-Medicaid-Coverage-For-Supportive-Housing-Services1.pdf.

[54] For more information see the Center’s Policy Basics: Project-Based Vouchers.