COVID Relief Provisions Stabilized Health Coverage, Improved Access and Affordability

End Notes

[1] Jessica Banthin and John Holahan, “Making Sense of Competing Estimates: The COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Health Insurance Coverage,” Urban Institute, August 2020, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102777/making-sense-of-competing-estimates_1.pdf. These estimates exclude some scenarios that assumed higher unemployment rates than actually occurred.

[2] John Holahan and A. Bowen Garrett, “Rising Unemployment, Medicaid and the Uninsured,” Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2009, https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/7850.pdf.

[3] Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker, “How does cost affect access to care?” January 14, 2021, https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/cost-affect-access-care/#:~:text=Source%3A%20KFF%20analysis%20of%20National%20Health%20Interview%20Survey,is%20higher%20than%20the%20share%20of%20insured%20adults.

[4] Jennifer M. Haley, Julia Long, and Genevieve M. Kenney, “Parents with Low Incomes Faced Greater Health Challenges and Problems Accessing and Affording Needed Health Care in Spring 2021,” Urban Institute, January 2022, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/105304/lowinc1_1.pdf.

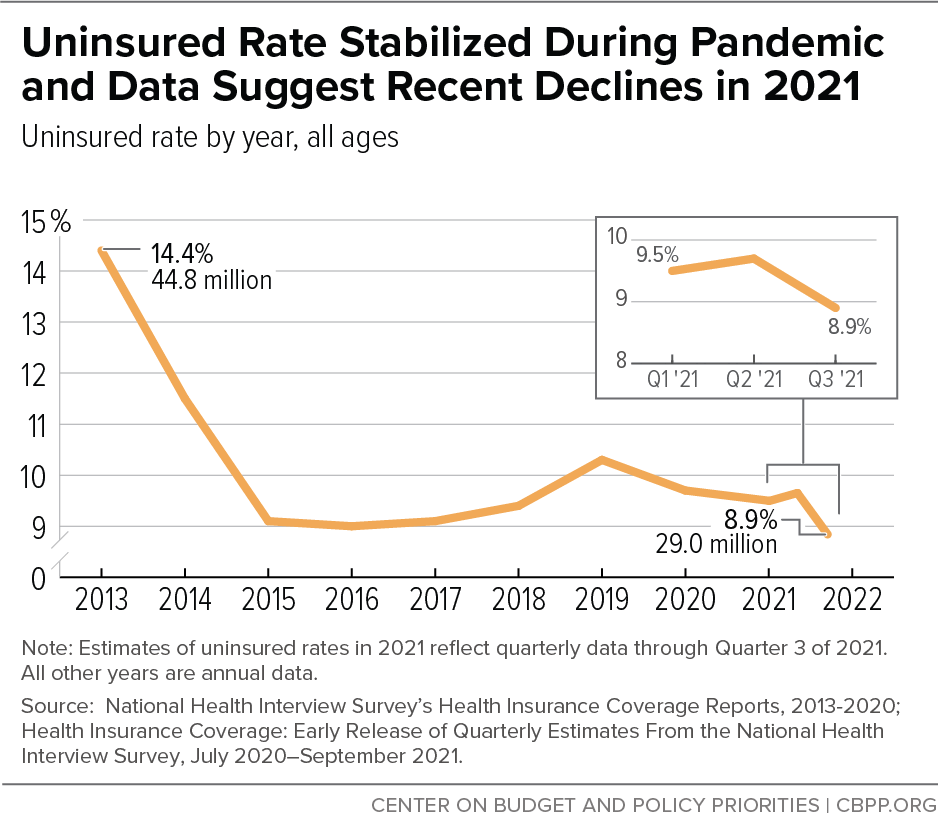

[5] Robin A. Cohen and Amy E. Cha, “Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Quarterly Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, July 2020-September 2021,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, January 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/Quarterly_Estimates_2021_Q13.pdf. Joel Ruhter et al., “Tracking Health Insurance Coverage in 2020-2021,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, October 29, 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/tracking-health-insurance-coverage.

[6] All states have implemented continuous coverage. States may still terminate coverage under limited circumstances, such as an enrollee moving out of state or requesting to terminate coverage.

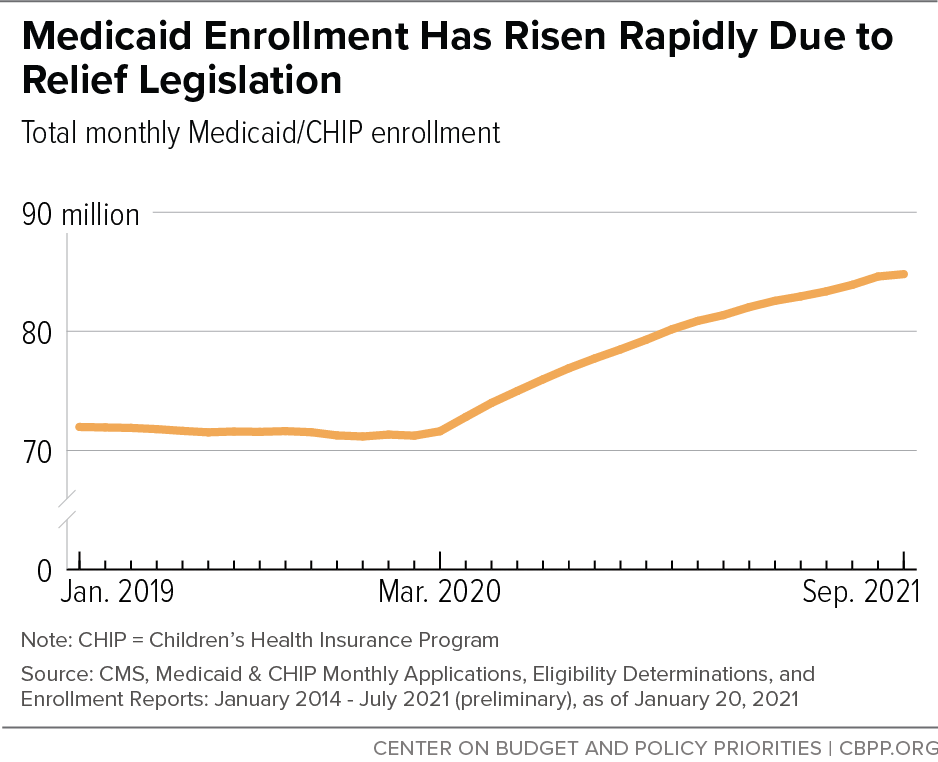

[7] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment Data, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/national-medicaid-chip-program-information/medicaid-chip-enrollment-data/monthly-medicaid-chip-application-eligibility-determination-and-enrollment-reports-data/index.html. September 2021 data are preliminary.

[8] CBPP analysis of data from states’ websites, which are typically revised but track well with CMS data. The 33 states with available data through December 2021 comprise roughly 70 percent of overall Medicaid enrollment and have grown at roughly the same rate as the 40 states (comprising roughly 92 percent of overall Medicaid enrollment) with website data through September 2021. Also, the large majority of states have continued to see increases in enrollment up through the latest month of available data.

[9] Michael Karpman and Stephen Zuckerman, “The Uninsurance Rate Held Steady during the Pandemic as Public Coverage Increased: Trends in Health Insurance Coverage between March 2019 and April 2021,” Urban Institute, August 18, 2021, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/uninsurance-rate-held-steady-during-pandemic-public-coverage-increased.

[10] Seasonally adjusted, total non-farm payroll. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[11] CMS Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment Data, op. cit. September 2021 data are preliminary.

[12] CMS, “Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment Trends Snapshot,” July 2021, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/national-medicaid-chip-program-information/downloads/july-2021-medicaid-chip-enrollment-trend-snapshot.pdf.

[13] CBPP analysis of 2019 American Community Survey. Black and Latino people are more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid largely because they are more likely to live in families with low incomes, a legacy rooted in unequal opportunities due to racism and discrimination.

[14] CBPP analysis of Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. It is uncertain why Latino people experience more frequent disruptions in Medicaid coverage, but reasons could include higher rates of income volatility or administrative obstacles to renewing coverage, such as language barriers.

[15] CBPP analysis of Medicaid enrollment data from the following states that present enrollment by race and ethnicity on their websites: Arizona, California, Connecticut, Maryland, Michigan, New York, Oklahoma, and Utah.

[16] Estimates are for uninsured non-elderly adults potentially eligible for marketplace coverage in HealthCare.gov states. D. Keith Branham et al., “Access to Marketplace Plans with Low Premiums on the Federal Platform,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, March 31, 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/access-marketplace-plans-low-premiums-uninsured-american-rescue-plan.

[17] Sarah Lueck and Tara Straw, “Recovery Legislation Should Build on ACA Successes to Expand Health Coverage, Improve Affordability,” CBPP, April 8, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/recovery-legislation-should-build-on-aca-successes-to-expand-health-coverage.

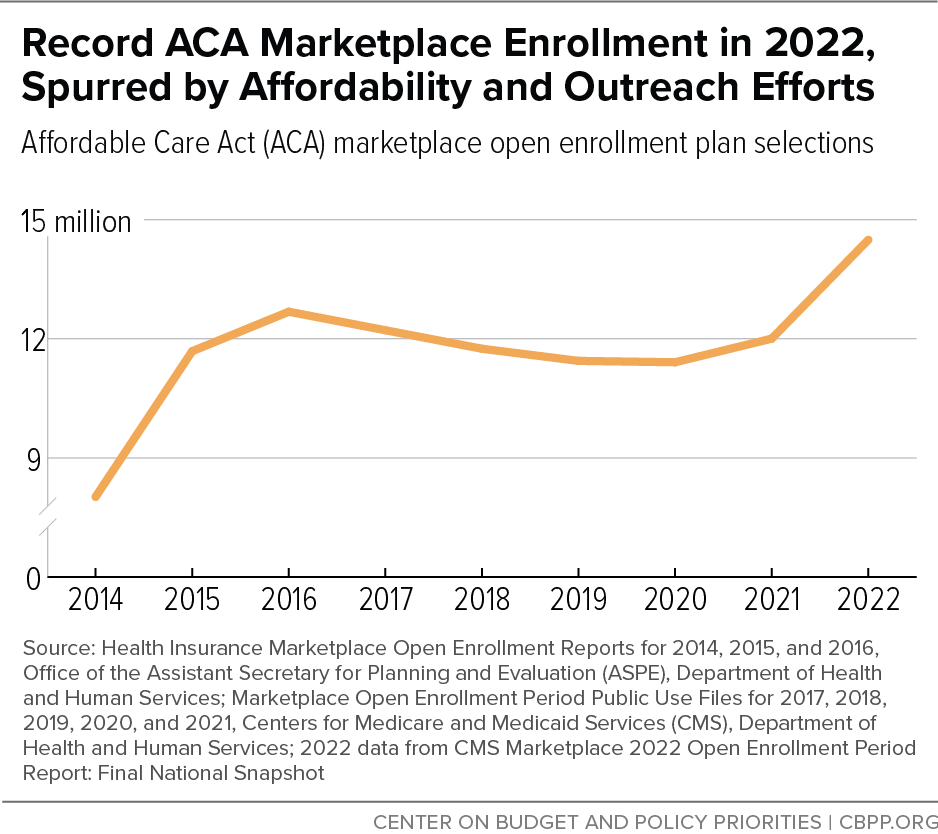

[18] Tara Straw, “Marketplace Poised for Further Gains as Open Enrollment Begins,” CBPP, October 29, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/marketplaces-poised-for-further-gains-as-open-enrollment-begins.

[19] CMS, “Marketplace 2022 Open Enrollment Period Report: Final National Snapshot,” January 27, 2022, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/marketplace-2022-open-enrollment-period-report-final-national-snapshot; CMS, “Health Insurance Exchanges 2020 Open Enrollment Report,” April 1, 2020, https://www.cms.gov/files/document/4120-health-insurance-exchanges-2020-open-enrollment-report-final.pdf

[20] CMS, “Biden-Harris Administration Announces 14.5 Million Americans Signed Up for Affordable Health Care During Historic Open Enrollment Period,” January 27, 2022, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/biden-harris-administration-announces-145-million-americans-signed-affordable-health-care-during.

[21] Straw, op. cit. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “HHS Announces the Largest Ever Funding Allocation for Navigators,” April 21, 2021, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/04/21/hhs-announces-the-largest-ever-funding-allocation-for-navigators.html.

[22] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Biden-Harris Administration Quadruples the Number of Health Care Navigators Ahead of HealthCare.gov Open Enrollment Period,” August 27, 2021, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/08/27/biden-harris-administration-quadruples-number-health-care-navigators-ahead-healthcare-open-enrollment-period.html.

[23] Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “Reaching the Remaining Uninsured: An Evidence Review on Outreach & Enrollment Strategies,” Issue Brief No. HP-2021-21, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, October 1, 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/reaching-remaining-uninsured-outreach-enrollment.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Branham et al., op. cit.

[26] Ruhter et al., op. cit. Karpman and Zuckerman, op. cit.

[27] Bureau of Labor and Statistics, “2020 Results of the Business Response Survey,” https://www.bls.gov/brs/2020-results.htm; Paul Fronstin and Stephen A. Woodbury, “How Many Americans Have Lost Jobs with Employer Health Coverage During the Pandemic?” Commonwealth Fund, October 7, 2020, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/oct/how-many-lost-jobs-employer-coverage-pandemic.

[28] COBRA is named for the 1985 Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act. COBRA coverage allows people who lose their jobs to retain employer-based coverage for up to 18 months, but it ordinarily must be paid for by the individual.

[29] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medicaid Emergency Authority Tracker: Approved State Actions to Address COVID-19,” July 1, 2021, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/medicaid-emergency-authority-tracker-approved-state-actions-to-address-covid-19/. Four additional states (Arizona, Montana, Rhode Island, and Washington) took up the option but later rescinded it without implementing.

[30] Requirements for grandfathered and non-grandfathered plans differ, and requirements do not apply to short-term, limited duration plans. For more information see CBPP, “Coverage for COVID-19 Testing, Vaccinations, and Treatment,” updated January 12, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/coverage-for-covid-19-testing-vaccinations-and-treatment.

[31] Tracking Accountability in Government Grants System, “Testing, Treatment, and Vaccine Administration for the Uninsured,” Department of Health and Human Services, accessed January 25, 2022, https://taggs.hhs.gov/Coronavirus/Uninsured.

[32] CMS, “Medicaid and CHIP and the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency: Preliminary Medicaid and CHIP Data Snapshot, Services through August 31, 2021,” https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/downloads/covid-19-medicaid-data-snapshot-08-31-2021.pdf.

[33] Priya Chidambaram, “Over 200,000 Residents and Staff in Long-Term Care Facilities Have Died From COVID-19,” Kaiser Family Foundation, February 3, 2022, https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/over-200000-residents-and-staff-in-long-term-care-facilities-have-died-from-covid-19/.

[34] Molly O’Malley Watts, MaryBeth Musumeci, and Meghana Ammula, “State Medicaid Home & Community-Based Services (HCBS) Programs Respond to COVID-19: Early Findings from a 50-State Survey,” Kaiser Family Foundation, August 10, 2021, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/state-medicaid-home-community-based-services-hcbs-programs-respond-to-covid-19-early-findings-from-a-50-state-survey/.

[35] Gideon Lukens and Breanna Sharer, “Closing Medicaid Coverage Gap Would Help Diverse Group and Narrow Racial Disparities,” CBPP, June 14, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/closing-medicaid-coverage-gap-would-help-diverse-group-and-narrow-racial.

[36] Danilo Trisi et al., “Recovery Legislation Provides Historic Opportunity to Advance Racial Equity,” CBPP, June 2, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/recovery-legislation-provides-historic-opportunity-to-advance.

[37] CMS, “Fact Sheet: Medicaid & CHIP and the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency,” May 14, 2021, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-medicaid-chip-and-covid-19-public-health-emergency.

[38] Jennifer Wagner and Judith Solomon, “Continuous Eligibility Keeps People Insured and Reduces Costs,” CBPP, May 4, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/continuous-eligibility-keeps-people-insured-and-reduces-costs.

[39] Sarah Sugar et al., “Medicaid Churning and Continuity of Care: Evidence and Policy Considerations Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, April 12, 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/265366/medicaid-churning-ib.pdf.

[40] Jennifer Wagner, “Streamlining Medicaid Renewals Through the Ex Parte Process,” CBPP, March 4, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/streamlining-medicaid-renewals-through-the-ex-parte-process.

[41] Cynthia Cox, Karen Pollitz, and Giorlando Ramirez, “How Marketplace Costs and Premiums Will Change if Rescue Plan Subsidies Expire,” Kaiser Family Foundation, September 24, 2021, https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/how-marketplace-costs-premiums-will-change-if-rescue-plan-subsidies-expire/.

[42] Lueck and Straw, op. cit.

[43] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Cost-Sharing for Plans Offered in the Federal Marketplace, 2014-2021,” January 15, 2021, https://www.kff.org/slideshow/cost-sharing-for-plans-offered-in-the-federal-marketplace/.

[44] D. Keith Branham et al., “Health Insurance Deductibles Among HealthCare.Gov Enrollees, 2017-2021,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, January 13, 2022, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/marketplace-deductibles-federal-platform-2017-2021.

[45] Sarah Lueck, “Recovery Legislation Should Reduce Marketplace Deductibles, Other Cost Sharing,” CBPP, May 19, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/recovery-legislation-should-reduce-marketplace-deductibles-other-cost-sharing.

[46] Aviva Aron-Dine et al., “Larger, Longer-Lasting Increases in Federal Medicaid Funding Needed to Protect Coverage,” CBPP, May 5, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/larger-longer-lasting-increases-in-federal-medicaid-funding-needed-to-protect.

[47] Jennifer Sullivan, “States Are Using One-Time Funds to Improve Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Services, But Longer-Term Investments Are Needed,” CBPP, September 23, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-are-using-one-time-funds-to-improve-medicaid-home-and-community-based.

[48] O’Malley Watts, Musumeci, and Ammula, op. cit.