- Home

- Food Assistance

- SNAP Includes An Extensive Payment Accur...

SNAP Includes an Extensive Payment Accuracy System

Performance Measures Should Also Emphasize Access and Customer Service

By the end of June, the Agriculture Department (USDA) will release overpayment and underpayment error rates for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits for fiscal year 2022 derived from the program’s extensive quality control process. These will be the first national and state-level SNAP error rates published since before the COVID-19 pandemic. The error rates may be higher than pre-pandemic because in 2022 states were still being affected by some of the ongoing challenges of the pandemic. These rates should be interpreted through the lens of what states accomplished during the pandemic and the key role SNAP played in preventing what could have been a surge in food insecurity.

Beginning in spring 2020, Congress and USDA provided for temporary measures in SNAP that increased benefits and gave states flexibility to prioritize processing new applications and keeping current participants connected to SNAP. Hunger was poised to soar at the outset of the pandemic — food insecurity rose more than 30 percent in the Great Recession — but program changes helped SNAP respond quickly to support individuals and families during periods of unemployment, earnings loss, and uncertainty. Largely thanks to these and other relief efforts, food insecurity held steady in 2020 and 2021 and, for households with children, reached a two-decade low.[1]

SNAP’s relief measures, including both benefit increases and added state administrative flexibilities, were largely still in effect in fiscal year 2022. These measures helped households grapple with the continued effects of the pandemic, including food price inflation, and assisted state agencies in managing ongoing workload challenges. Both have now ended or will end imminently.

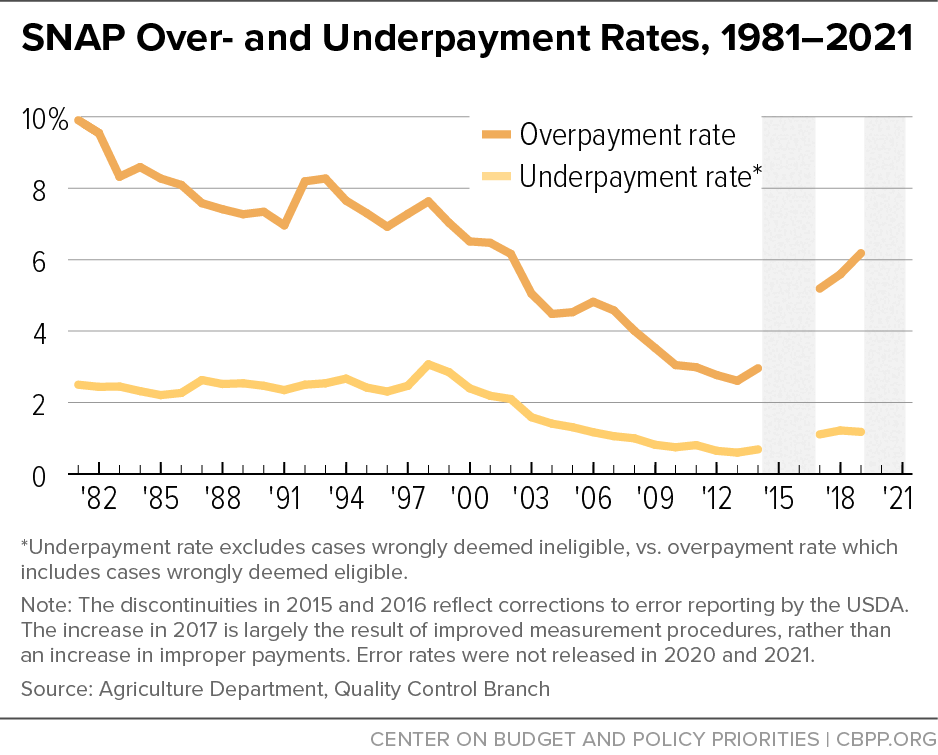

In 2019, before the pandemic, the SNAP overpayment rate (the percentage of benefit dollars issued to ineligible households or to eligible households above what program rules direct) was 6.18 percent, and the underpayment error rate (the percent by which eligible, participating households received smaller benefits than program rules direct) was 1.18 percent.[2] Congress and USDA suspended the error rate reporting process for fiscal years 2020 and 2021 in response to the conditions during the pandemic, though most states continued to conduct reviews for internal monitoring purposes.

SNAP’s pandemic-related flexibilities were intended to help states process new applications and keep people connected to SNAP during a temporary time of severe economic challenges. They were successful at meeting that goal; SNAP participation rates rose and food insecurity held steady. In fact, one measure of SNAP access reached its highest-ever level in 2021. These flexibilities may, however, also have contributed somewhat to higher over- and underpayment error rates in some states because less frequent state contact with SNAP applicants and recipients can make it more difficult for state staff to determine benefits accurately.

SNAP’s error rates compare favorably to many other government activities. For example, the tax gap ― or the difference between taxes owed and taxes paid ― averaged 15 percent in tax years 2014-2016 (the most recently studied years), according to Internal Revenue Service estimates. For some categories of income, the share that is misreported is particularly high: 57 percent of non-farm proprietor income, a subset of business income reported on individual returns (the largest source of the tax gap), was misreported in 2014-2016.[3]

Payment accuracy is an important measure of SNAP’s performance; the error rate is the primary performance measure for accountability at local SNAP offices and plays a major role in driving state and federal program officials’ decisions. States and USDA rightfully devote considerable attention to achieving low error rates. But an overemphasis on payment accuracy, to the exclusion of measuring SNAP’s core goals, risks leaving policymakers and the public with inadequate information about how well the program is working for households.

For example, is it reaching a large share of eligible households? How difficult is it for people to access the program through state offices, online, or through call centers? Is the program accessible to people in rural or remote areas, to people with disabilities, or people who lack a fixed permanent address? These kinds of performance metrics are also important. A program should not be considered successful if it has high payment accuracy but low take-up, or if challenges in accessing it impose a significant tax on participants in terms of time and resources.

The upcoming farm bill, in which Congress will reauthorize SNAP and other programs under the Agriculture Committee’s jurisdiction, is an opportunity for improvements to SNAP performance metrics that would better balance payment accuracy with customer service and ensuring timely access. It is critical that SNAP’s success also be measured for the way it centers participants’ experience and makes benefits accessible to people in all areas of the country.

SNAP Has One of the Most Rigorous Payment Accuracy Systems

For decades SNAP has had among the most rigorous eligibility determination and payment accuracy measurement systems of any federal benefit program. SNAP was among the few programs to already be meeting the high standards of the Improper Payments Act when it was enacted in the early 2000s.

Emphasis on achieving and maintaining low error rates pervades SNAP culture and program operations. A significant number of federal and state personnel are assigned to upfront eligibility determinations and program integrity monitoring. USDA and the states, which administer SNAP under federal guidelines, track SNAP error rates throughout the year and share best practices. The error rate is the primary performance measure for accountability at local SNAP offices and even for individual state staff.

It also plays a major role in driving state and federal program officials’ decisions, in ways that have driven attention to payment accuracy but also can result in barriers that make it harder for households to access needed benefits.

Upfront Eligibility Determinations Require Substantial Scrutiny

Under SNAP’s rules, households applying for SNAP must report their income and other relevant information, such as household members, shelter costs, immigration status, and other factors relevant for determining eligibility, factoring in available deductions, and calculating benefit levels. A state eligibility worker interviews a household member and verifies the accuracy of the information using data matches or paper documentation from the household or by contacting a knowledgeable party, such as an employer or landlord. Households must reapply for benefits periodically, usually every six or 12 months, and between reapplications must report income and certain other changes that would affect their eligibility or benefit level.

QC System Rechecks for Accuracy

In addition to these upfront eligibility certification activities, the SNAP QC system requires states each month to select a representative, random sample of SNAP cases (totaling about 50,000 cases nationally over the year), and an independent state QC reviewer checks the accuracy of the state’s eligibility and benefit decisions for each household within federal guidelines. The QC review includes another detailed examination of the household’s circumstances for the sample month, including another interview with a household member and additional, more extensive documentation. Federal officials then re-review a subsample of about half of states’ sampled cases to ensure the validity and integrity of each state’s review.

QC System Produces Error Rates, Assesses Fiscal Sanctions for Poor Performance

USDA annually releases state and national payment error rates based on these reviews. These error rates measure how accurately states determine eligibility and benefit amounts. States are subject to fiscal penalties if their error rates are substantially above the national average for two or more years in a row. In addition, to help lower error rates, most states (except the highest performers) must submit a corrective action plan for USDA approval outlining measures they will take to address the root causes of errors.

USDA has issued error rates every year since the early 1980s, except for two short gaps. In addition to the congressionally directed suspension of the QC system during the COVID pandemic, discussed below, USDA did not report SNAP QC error rates for fiscal years 2015 or 2016 due to a USDA Office of Inspector General report that drew attention to concerns about data quality issues with error rates in many states. During this time, USDA conducted detailed reviews in all states and took action to address the quality and consistency of the measure.

The 2018 farm bill required USDA to update its regulations to ensure that the QC system produced accurate, statistically valid results and to regularly review states’ QC processes. USDA issued an interim final rule in August 2021. The revised SNAP error rates for 2017 through 2019 were higher than the rate published in 2014; USDA attributed the increase to an improved measurement process, rather than an actual increase in improper payments. Also, as noted below, the rate of erroneous underpayments does not include cases wrongly deemed ineligible for benefits. (See Figure 1.)

Most QC Errors Represent Mistakes, Not Fraud

Relatively few SNAP errors represent dishonesty or fraud on the part of recipients, such as lying to eligibility workers to get benefits. Given its nature, the exact extent of fraud is difficult to pinpoint, but it is clear that the overwhelming majority of SNAP errors result from honest mistakes by recipients, eligibility workers, data entry clerks, or computer programmers. USDA reports that about half of overpayments and 80 percent of underpayments were states’ fault in fiscal year 2019;[4] most others resulted from simple errors by households, not intentional fraud. Individual households must pay back overpayments — even when due to the state agency’s error — and the state issues corrections for underpayments.

Improper Denials and Terminations Are Not Included in Underpayments

SNAP’s underpayment error rate understates the magnitude of underpayments because it covers only instances where states gave some benefits to a household but not as much as the household should have received under SNAP rules. It does not include cases when an applicant was incorrectly deemed ineligible for benefits. USDA and states use a separate sample of denials and terminations to estimate each state’s “case and procedural error rate” (CAPER). This rate measures whether states properly denied, suspended, or terminated SNAP benefits and properly notified those households of its decision in the required timeframes.

Nationally, in 2019 over one-third of states’ actions to deny or terminate SNAP benefits were found to be improper. Ten states’ CAPERs approached or exceeded 50 percent. The CAPER is not directly comparable to the overpayment and underpayment error rates. It is based on a separate state sample of denials, suspensions, and terminations, and the review of the state’s decision is not as rigorous as for the payment errors. USDA does not assess or report whether the household was ineligible for a reason other than the reason given by the state or the amount of benefits that improperly denied households would have received.

States are not penalized for persistently high CAPERs, which means that states and USDA spend less time and energy analyzing and trying to fix processes that result in a large share of eligibility denials and terminations being improper. The CAPER review primarily measures whether the state followed proper procedures, such as whether the state issued a clear notice or followed other proper procedures.

But more attention is warranted here. When a state does wrongly deny or terminate benefits for a household, it is withholding food assistance that the household qualifies for and needs to make ends meet. Missing out causes significant harm to households who can least afford it — and significantly more harm than is done when agencies modestly overpay a household that meets the stringent eligibility requirements and has low income.

In Pandemic, Congress and USDA Modified SNAP’s Procedures to Prioritize Food Security

Congress enacted and USDA implemented several temporary changes to SNAP at the onset of the pandemic to help the program push back against the risk of food insecurity and to help states weather the extraordinary circumstances of being forced into remote operations. Additional benefits helped households afford food during a time of considerable economic strain. And states had new options to simplify how they ran the program, which helped them adjust to remote operations and significant workload strain as many agencies saw their caseloads rise and staffing fall.

During the Great Recession, the share of households that were food insecure rose from 11.1 percent in 2007 to 14.7 percent in 2009, according to Agriculture Department estimates. Yet because of states’ ability to take advantage of administrative flexibilities, combined with other COVID relief efforts and the program’s structural ability to respond to increased need, the typical annual measure of food insecurity in 2020 and 2021 held steady at just over 10 percent, statistically unchanged from the 2019 level.[5] In fact, during the pandemic food insecurity improved for households headed by a Black adult and reached a two-decade low for households with children, thanks largely to SNAP and other relief efforts.

It’s clear that SNAP and other forms of economic support prevented food insecurity from surging during the pandemic the way it did during the Great Recession. The two major reasons for SNAP’s success in pushing back against food hardship were increased benefits and administrative flexibility that allowed states to keep people already participating connected to SNAP while processing new applications for families and individuals newly experiencing financial challenges.

These temporary changes likely will influence SNAP QC error rates to varying degrees. All of the changes ended by the summer of 2023, or will soon end.

States Issued Emergency Allotments From Spring 2020 Through February 2023

Congress enacted a temporary SNAP benefit increase in March 2020 to “address temporary food needs” during the pandemic.[6] Beginning in March 2020, under a Trump Administration interpretation, a household’s EA was the amount needed to raise the household’s benefits to the SNAP maximum benefit for its household size.[7] However, this approach resulted in the lowest-income SNAP households ― the nearly 40 percent of SNAP households that already received the maximum benefit — missing out on additional benefits. The Biden Administration revised this policy, and, from April 2021 through February 2023 when the authority for EAs ended, all households in states issuing EAs received EAs of at least $95 a month. The total average SNAP benefit during this time was roughly $9 per person per day.

QC Reviews Did Not Take EAs Into Account, Which Will Overstate SNAP Errors

USDA instructed SNAP QC reviewers to review cases to evaluate whether the eligibility worker determined the regular SNAP benefit accurately, not the amount with the EA included. This approach will mean that the errors the QC system reports will likely overstate the amount of over- and under-issuances in terms of the benefits households should have received and the cost to the government.

For example, if a state failed to count the full amount of income for a household of two and the QC reviewer determined the SNAP benefit under regular SNAP rules should have been $250 instead of the $350 the eligibility worker determined, the QC system in fiscal year 2022 would include this as a $100 overpayment — even though, with the EAs in place, the state issued and the household received the right amount (the $459 maximum benefit for a household of two). Conversely, a supposed $100 underpayment for failure to correctly calculate a deduction under regular SNAP program rules would not actually be an underpayment from the household or government spending perspective with the EAs in place; the household would have rightly received the maximum, EA-adjusted benefit, regardless of the error.

SNAP eligibility workers understood that with the EAs in place, getting income or deductions exactly right was less important as long as the family was eligible for SNAP. With the EAs in place, most households received the maximum benefit.

State Certification Flexibilities Prioritized SNAP Access

Early in the pandemic, SNAP caseloads were rising at the same time that states needed to quickly adapt to remote operations. Congress and USDA provided state agencies with temporary flexibilities to help them prioritize their ability to process new applications and keep participating households connected to SNAP. Specifically, states could waive interview requirements at initial certification and recertification, lengthen certification periods so households did not need to reapply as often, and adapt telephone signatures to ease remote application processing. Almost every state used one or more these options during the pandemic.[8]

These administrative flexibilities played a major role in states’ ability to keep eligible households connected to SNAP. In 2021, despite the workforce challenges of the pandemic, states in the aggregate attained the highest Program Access Indices (PAI) on record (at 77 percent nationally). PAI is one of USDA’s measures of the degree to which low-income people receive SNAP benefits and represents the average monthly number of SNAP participants as a share of all individuals in households with income below 125 percent of the poverty line.[9]

But the administrative flexibilities may have caused higher error rates. States use the interview and recertification process to confer with households about their income, expenses, and other circumstances, so less frequent interviews and recertifications may contribute to modestly higher error rates. And, as noted above, in fiscal year 2022 EAs were in place in most states. This means that if the state made a modest error — such as using an income level to calculate benefits that was slightly too low — the QC system treated that as an error even if the household actually received the right benefit level because of the structure of the EAs. So, the easing up of the frequency of some of the checks may cause measured error rates to go up a lot more than the actual payments issued in error. And again, it was far more important that SNAP be as accessible as possible during the pandemic’s unprecedented challenges.

QC Was Suspended Nationwide for Parts of Fiscal Year 2020 and 2021

USDA allowed states to suspend QC operations from March through May of 2020 because of “extraordinary temporary situations” that made it difficult for states to complete reviews as they adapted to remote operations and other workload issues. Congress then extended the suspension through June 2021. USDA encouraged states to continue conducting QC reviews during this period for internal management purposes, and most states did. But because states were not required to report results, USDA determined it could not establish national SNAP error rates for fiscal years 2020 or 2021. States started reporting error rates to USDA in July 2021, so QC operations are fully underway for fiscal year 2022, even though many of the pandemic-related flexibilities were still in place in many states.

State and Federal Policymakers Should Prioritize Payment Accuracy and Client Access

It is appropriate that Congress, USDA, and states take their roles seriously as stewards of public funds and emphasize program integrity throughout SNAP program operations. But they should also ensure that a program with a core purpose of addressing food insecurity reaches as many people who qualify as possible. During the COVID pandemic, Congress and USDA asked states to quickly shift that balance more toward the goal of access, to ensure that households could get or keep food assistance to prevent hardship.

Unfortunately, during more normal times, SNAP’s performance measurement system is heavily tilted to payment accuracy. The program does far too little to measure and prioritize access. And policymakers and the public often lack adequate information about how well the program is performing in terms of the human experience of applying for and maintaining benefits.

The upcoming farm bill will be an opportunity for Congress and the Administration to strengthen SNAP’s performance measurement in ways that center participants’ experience and ensure SNAP is accessible to all people in all areas of the country.

The 2018 farm bill eliminated state performance bonuses that rewarded higher participation rates among eligible people and timely delivery of benefits but maintained fiscal penalties for high payment error rates. The result was to gives states an incentive to prioritize payment accuracy over access and customer service. We recommend two improvements to restore more balance to SNAP’s performance measurement system.

First, Congress should require USDA to continue to measure and report on SNAP participation rates and timeliness of application processing (including initial applications and applications for recertification). And, to the greatest extent possible, USDA should provide these metrics by subgroup of SNAP participants, such as people in rural and remote areas, older adults, people with disabilities, and people of all races and ethnicities. SNAP is the nation’s most effective tool at combating hunger, helping people across a range of demographic groups and reducing disparities that are due in large part to discrimination, economic differences by geography, and other factors.[10] But more could be done for SNAP to further reduce disparities and help participants position themselves to thrive. More information is also needed about the policies and procedures that states have in place that are most successful at improving the accessibility and timeliness of SNAP benefits.

Second, Congress should prepare to build a few key metrics ― or “vital signs” ― into state SNAP performance measures to give state and federal policymakers insight into the human experience of obtaining and retaining SNAP benefits. Such measures could include, for example:

- Call center answer rates and wait times, which can be caused by issues intrinsic to telephone service or can indicate more systemic problems;

- Procedural denials, that is, the number and percent of applications and recertifications that are denied or closed not because of financial ineligibility, but for procedural reasons, (for example, for failing to submit a recertification application, a missed interview, or incomplete verification);

- Churn, that is, the percent of cases that lose coverage during a renewal or periodic report and re-enroll within the following 90 days; and

- Customer satisfaction.

We recommend these vital signs as a starting point because they would provide a sense of how program operations are faring on the ground, while also being relatively feasible for states to implement. Additional measures may be worth pursuing over the longer term, but would likely need further testing and conversation with states to determine exactly how to calculate them and to ensure comparability across states.

Temporary Pandemic SNAP Benefits Will End in Remaining 35 States in March 2023

States Are Using Much-Needed Temporary Flexibility in SNAP to Respond to COVID-19 Challenges

End Notes

[1] Joseph Llobrera, “Food Insecurity at Two-Decade Low for Households with Kids, Signaling Successful Relief Efforts,” CBPP, September 9, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/food-insecurity-at-a-two-decade-low-for-households-with-kids-signaling-successful-relief.

[2] State-level over- and underpayment rates are available at USDA, Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP Quality Control,” https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/quality-control.

[3] See gross tax gap figure from Internal Revenue Service, “Federal Tax Compliance Research: Tax Gap Estimates for Tax Years 2014-2016,” August 2022, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p1415.pdf.

[4] USDA, Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP Quality Control Annual Report,” Fiscal Year 2019, Table 15, p. 31, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/SNAP_QC_2019.pdf.

[5] Alisha Coleman-Jensen et al., “Household Food Security in the United States in 2020,” USDA, September 2021, https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=102075.

[6] Dottie Rosenbaum, Katie Bergh, and Lauren Hall, “Temporary Pandemic SNAP Benefits Will End in Remaining 35 States in March 2023,” CBPP, February 6, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/temporary-pandemic-snap-benefits-will-end-in-remaining-35-states-in-march.

[7] SNAP’s maximum benefits are based on the cost of the “Thrifty Food Plan,” a USDA estimate of the cost of purchasing and preparing a nutritionally adequate diet, consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, for people in low-income households, assuming they take significant steps to stretch their food budgets. SNAP households are expected to spend 30 percent of their net income on food; SNAP makes up the difference between the household’s contribution and the maximum benefit.

[8] CBPP, “States are Using Much-Needed Temporary Flexibility in SNAP to Respond to COVID-19 Challenges,” updated January 25, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/states-are-using-much-needed-temporary-flexibility-in-snap-to-respond-to.

[9] USDA, “SNAP Program Access Index,” https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/program-access-index.

[10] Ty Jones Cox, “SNAP Is and Remains Our Most Effective Tool to Combat Hunger,” CBPP, February 14, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/snap-is-and-remains-our-most-effective-tool-to-combat-hunger.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise