As Congress considers appropriations bills for fiscal year 2024, new data confirm that WIC needs significant additional funding — well beyond the amounts provided in current House and Senate bills — to maintain a long-standing, bipartisan commitment to avoid turning away eligible families, and to provide participants with the current science-based food benefit.

Under the House bill, which may come to the floor for a vote this week, we estimate that 650,000 to 750,000 eligible people — primarily toddlers, preschoolers, and postpartum adults — would be turned away from the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).[1] (This number is in comparison to the average number of people who would be served each month if the program was fully funded.) Another 4.6 million toddlers and preschoolers and pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding participants would have their benefits cut significantly. In total, the House bill would cut food assistance for, or take it away altogether from, roughly 5.3 million young children and pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding adults.

We estimate that even the Senate’s higher funding level would require states to turn away 700,000 to 800,000 postpartum adults and young children, but those who are enrolled in WIC would receive full benefits. Table 1 below provides estimates of the reduction in the number of people WIC would serve in each state under both bills, relative to estimated participation, if the funding gap is not filled.

Time is of the essence. States need more money at the start of the fiscal year, along with an assurance that full-year funding will be adequate, or they may well start taking steps to cut enrollment even before final funding levels are settled for the year.

WIC provides critical nutrition benefits, breastfeeding support, and other vital services to low-income pregnant and postpartum people, infants, and young children under age 5 who are at nutritional risk. In recognition of WIC’s positive impacts on health and developmental outcomes, policymakers have adhered to a bipartisan commitment for more than 25 years to provide the program sufficient funding to serve all eligible applicants.

To maintain this commitment and provide full benefits, WIC will need $7.2 to $7.3 billion next fiscal year, we estimate based on the most recent data. That is $900 million to $1 billion above the President’s budget request and the amount in the Senate’s appropriations bill, and $1.7 billion to $1.8 billion above the level provided in the House bill.

The House Republicans’ appropriations bill, which passed out of committee on a party-line vote, falls dramatically short of WIC’s fiscal year 2024 funding needs. And it would weaken the program’s science-based benefits by sharply reducing the fruit and vegetable benefit that was increased two years ago on the recommendation of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

The bipartisan bill the Senate Appropriations Committee unanimously advanced in June funds WIC at the level requested in the President’s budget, $6.3 billion. This amount was thought to be sufficient when the Biden Administration put together its budget earlier this year, but recent data have shown that it falls short of the funding that’s needed to provide full benefits and to keep people off waiting lists and serve everyone who applies and is eligible. The Senate bill, like the President’s budget, maintains the integrity of WIC’s food benefits, including the science-based fruit and vegetable benefit.

WIC funding needs have increased because the number of pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding adults, infants, and young children participating in the program has risen more than expected when the President’s budget was being developed — as have food costs — substantially increasing the cost of serving all eligible applicants and providing participants with the full food benefit.

Congress must provide WIC the resources it needs or the program will be forced to turn away eligible low-income families seeking support. Under a funding shortfall, states would have to serve fewer young children and new parents than they are currently serving and are projected to serve next year (if full funding is made available). To do this, they would put some eligible applicants on waiting lists and would be unable to continue serving some participants when they reached the end of their current eligibility period and needed to recertify to continue receiving benefits. States can also reduce enrollment by scaling back outreach, clinic hours, or enrollment simplification efforts, and eligible people who otherwise would have sought benefits could also be discouraged from applying when they learn about waitlists.

Turning away eligible low-income families would deny them nutrition assistance and other vital services that young children need during critical periods of early brain development, and that pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding adults need to support their health. The impacts of food insecurity and hunger on children are well-documented, with even short periods of food insecurity resulting in harm to their mental and physiological development and increased risk of adverse health outcomes.[2] WIC participation contributes to lower prevalence of food insecurity, along with healthier births, more nutritious diets, and higher academic achievement for students.[3]

If, as is likely, Congress enacts a short-term continuing resolution in September because its full-year appropriations bills aren’t completed, it will be critical that it include the additional resources WIC needs to continue providing current benefits to all eligible people who seek them — and as much funding certainty for the full fiscal year as is possible to prevent state WIC programs from ramping down enrollment before funding bills are finalized. Even temporary uncertainty about annual funding could drive states to take measures to curtail enrollment in anticipation of a possible shortfall later in the fiscal year. If final full-year funding is inadequate, the longer that state WIC programs wait to take steps to reduce enrollment, the more extreme the measures they will have to take in the remaining months in order to bring annual expenses in line with available funding. Policymakers must act swiftly to resolve this uncertainty and meet WIC’s funding needs to avoid jeopardizing eligible families’ access to WIC, which could have lasting nutritional and health consequences.

Rising Participation and Food Costs Are Increasing WIC’s Funding Needs

Several factors are increasing WIC’s future funding needs. First, WIC participation has been rising over the last couple of years, with more rapid growth in this fiscal year. This is a welcome development. Despite WIC’s strong long-term impacts, in recent years take-up rates among those eligible have been relatively low: only 50.2 percent program-wide in 2020, and even lower for pregnant people (45.6 percent) and children aged 1 through 4 (40.6 percent).[4] Federal and state policymakers have taken steps to make WIC easier to access and that work is starting to show results.

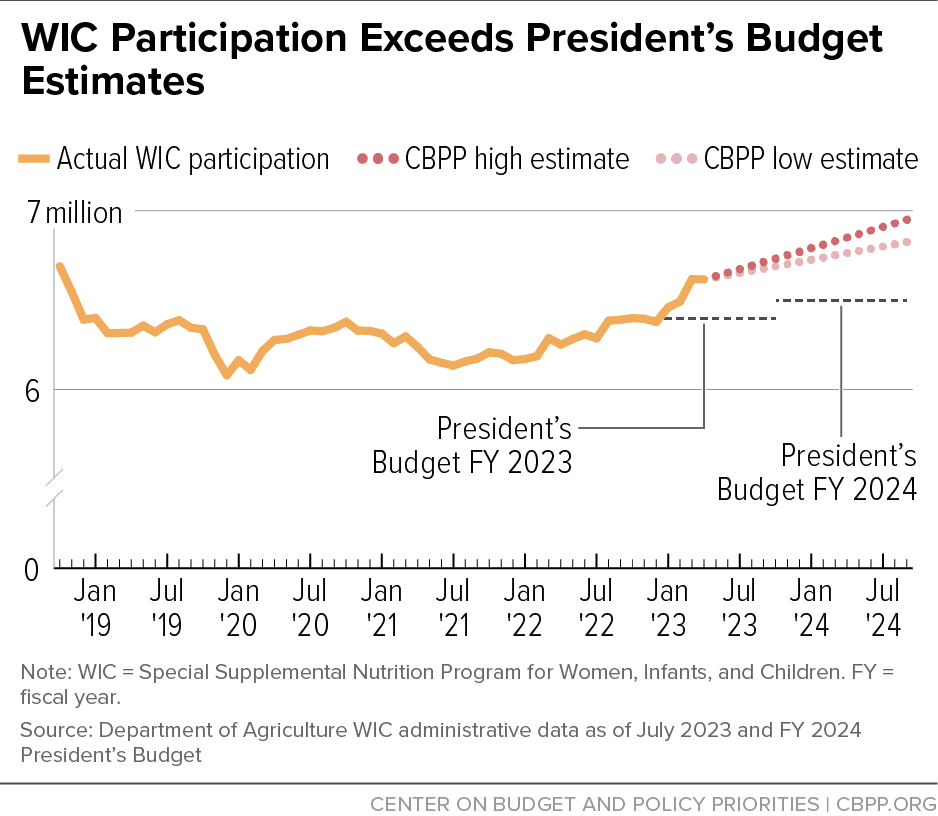

More rapid participation growth in fiscal year 2023 was not expected when the President’s budget was released, but data over the last few months have shown a clear upward trend: participation in the first seven months of fiscal year 2023 was 4.4 percent higher than in the first seven months of fiscal year 2022.

Based on current participation trends, we now estimate that average monthly participation for fiscal year 2023 will be about 6.55 million people. For fiscal year 2024 we estimate it will be 6.76 million to 6.84 million, which is above the 6.5 million that the Agriculture Department (USDA) previously forecasted in the President’s budget.[5] (See Figure 1.)

Recent increases are likely due to a combination of policy efforts to modernize the program and reduce participation barriers, such as providing flexibility to offer remote appointments; improving the shopping experience for participants; and enhancing WIC’s food packages, including the increase in the fruit and vegetable benefit. Additional funding for outreach and program modernization will soon be available, potentially driving participation and retention up further in coming years.

Food price inflation has also contributed to higher costs of providing benefits and will likely continue to be a factor in the short term. While prices are now leveling off, USDA’s forecasts for price increases in fiscal year 2023 remain well above typical increases in recent years.[6] Across all the foods WIC provides, the weighted average increase in fiscal year 2022 was about 10 percent; we estimate it will be about 8 percent in fiscal year 2023.[7]

Food price inflation impacts not only the program’s food costs but may also encourage higher rates of participation among eligible families who need additional assistance stretching their grocery budgets. Likewise, the end of SNAP’s temporary pandemic-related emergency allotments in most states in March might be making it harder for low-income families to afford groceries and therefore more likely to seek additional assistance through WIC and stay enrolled in the program longer. As WIC participants confront higher food prices and reduced SNAP benefits, they may also be redeeming more of the food benefits WIC provides, further increasing food costs.

Another factor influencing WIC’s food costs is an enhanced benefit for fruits and vegetables, first authorized in the American Rescue Plan and since continued with bipartisan support through appropriations laws. The enhanced benefit better aligns with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and recommendations from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. In fiscal year 2023, this science-driven (and hardly lavish) WIC benefit is providing $25 per month to buy fruits and vegetables for child participants, $44 for pregnant and postpartum participants, and $49 for breastfeeding participants.[8]

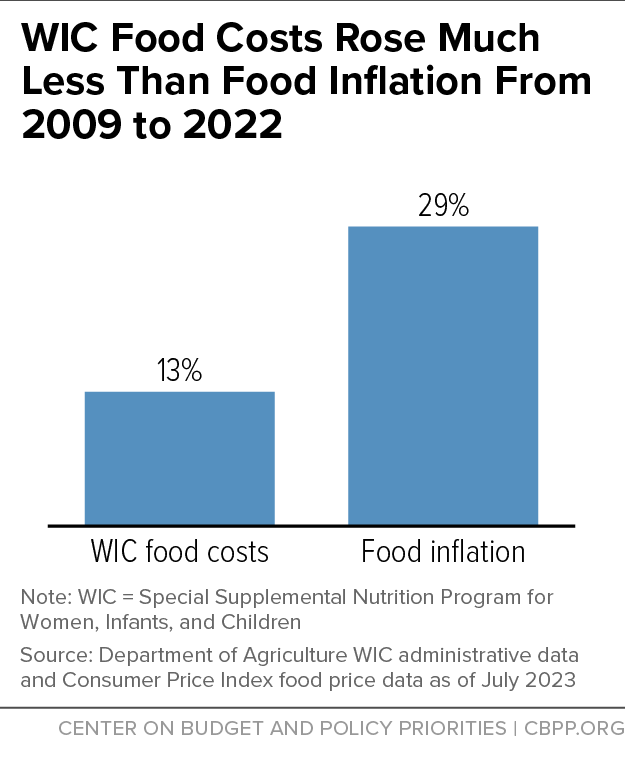

It is important to consider the recent increases in WIC food costs in the context of WIC’s long-standing history of very effectively containing food costs. Since 2009, when WIC’s current (but pre-enhanced-benefit) structure was set, overall food costs have risen 29 percent, compared to just 13 percent for WIC’s per-participant food costs — even with the substantial fruit and vegetable benefit increase. (See Figure 2.)

The two congressional chambers have taken very different approaches to WIC funding for 2024. However, neither the House nor Senate proposal would be sufficient to avoid turning eligible people away and to continue to provide the current science-based food benefit, based on current participation and food cost forecasts.

The bill advanced by House Republicans (H.R. 4368) would significantly underfund WIC and includes several harmful policy proposals that would undermine its science-based benefits.[9] The partisan House bill provides $6 billion in budget authority paired with a $500 million rescission. This represents a funding level that is $800 million below the President’s budget request (which we now know is itself quite inadequate) and $185 million below the enacted fiscal year 2023 level.

The House bill would also gut the enhanced fruit and vegetable benefit. Participants would be left with only $11 to $15 per month to purchase healthy produce, depending on the participant category, representing a 56 to 70 percent cut compared to current levels. This cut would allow the House’s inadequate funding level to cover more participants, but the funding provided is so low that it would still require waiting lists and force eligible children and postpartum people to be turned away. In addition to the 4.6 million children and pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding participants who would see their benefits slashed under the House proposal, we estimate that states would be forced to turn away 650,000 to 750,000 eligible applicants or recertifying participants.[10] The House funding level without the benefit cut would result in even deeper enrollment cuts, forcing states to cut average monthly participation by 1.45 million to 1.55 million people, compared to expected participation. Table 1 estimates the effect of this bill in each state.

The House proposal includes two other provisions that would override USDA decision-making about WIC’s food packages. The independent, science-driven process that determines WIC-eligible foods is one reason WIC has such well-documented health and nutrition benefits. Nutrition experts — not lawmakers or industry interests — should continue to drive this process.

The bipartisan Senate proposal (S. 2131) rejects the House’s harmful policy changes and would maintain both the current fruit and vegetable benefit and the integrity of the WIC food packages.[11] The Senate bill also provides the funding level requested in the President’s budget proposal, $6.3 billion, which is a $615 million increase over the enacted level for 2023. When the President’s budget was released, based on participation and food cost data available at the time, this funding level seemed sufficient to maintain the long-standing no-waitlist commitment and provide the current science-based food benefits.

Before the Senate Appropriations Committee unanimously voted to advance the Senate bill in June, agriculture subcommittee Chair Martin Heinrich committed to “monitoring participation and food costs so that we can provide enough funding to make sure that all eligible families who seek help from WIC can be served and receive the program’s current science-based food benefits.”[12] As more data have become available, it is now clear that even the Senate’s higher funding level is insufficient and would require states to turn away a monthly average of 700,000 to 800,000 people, primarily postpartum people and children, compared to expected participation in fiscal year 2024.[13] (Table 1 includes state-by-state estimates of this bill’s effects, as well.)

We estimate that WIC will need $7.2 to $7.3 billion — $900 million to $1 billion above the President’s budget request and the level provided by the Senate, and $1.7 billion to $1.8 billion above the level provided in the House bill — to continue to serve all eligible families who apply and to maintain the current science-based food benefit.

Any funding level that fails to serve all eligible WIC applicants would be contrary to more than 25 years of precedent. Every year since 1997, policymakers of both parties have provided sufficient funding to ensure that WIC can serve every eligible pregnant or postpartum person, infant, and young child who applies for benefits or must recertify.

Extensive research over more than four decades has shown that WIC participation is linked to significant benefits for health, nutrition, and developmental outcomes. That includes fewer premature births, fewer infant deaths, improved diet quality, lower prevalence of food insecurity, higher rates of childhood immunization, better access to health care, and numerous other benefits.[14] A funding shortfall would mean eligible low-income people would lose out on these benefits.

If Congress fails to pass timely full-year appropriation bills and instead relies on a short-term continuing resolution, it will be critical that policymakers provide WIC with significant additional resources and provide states with as much certainty as possible, as soon as possible, that WIC will have sufficient funding for the entire fiscal year.

Uncertainty about whether WIC would have adequate funding for the entire year poses a challenging dilemma for state officials. The longer that state WIC programs wait to take measures to reduce their monthly caseload, the deeper the cuts would have to be if funding is ultimately insufficient. If deeper cuts are needed, states could have to turn away applicants typically given higher priority, potentially affecting younger toddlers and those with health conditions.[15] Even temporary uncertainty while a short-term continuing resolution is in place could drive states to limit outreach, reduce clinic hours, leave staff positions vacant, or take other measures to tamp down enrollment and program costs in anticipation of funding falling short for the year.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| Estimated Impacts of House and Senate Appropriations Bills |

|---|

| State | People Turned Away Under Senate Bill | People Turned Away Under House Bill | People With Fruit and Vegetable Benefits Cut Under House Bill* | People Harmed Under House Bill** |

|---|

| Alabama | 13,000 | 12,200 | 79,800 | 92,000 |

| Alaska | 1,600 | 1,500 | 10,100 | 11,700 |

| Arizona | 15,600 | 14,500 | 95,600 | 110,100 |

| Arkansas | 6,700 | 6,300 | 41,200 | 47,400 |

| California | 112,200 | 104,700 | 687,900 | 792,500 |

| Colorado | 9,300 | 8,700 | 57,300 | 66,000 |

| Connecticut | 5,600 | 5,200 | 34,400 | 39,600 |

| Delaware | 2,100 | 2,000 | 13,000 | 15,000 |

| District of Columbia | 1,400 | 1,300 | 8,600 | 9,900 |

| Florida | 49,200 | 45,900 | 301,800 | 347,700 |

| Georgia | 23,000 | 21,400 | 140,900 | 162,300 |

| Hawai’i | 3,100 | 2,900 | 19,000 | 21,900 |

| Idaho | 3,500 | 3,200 | 21,300 | 24,600 |

| Illinois | 18,600 | 17,400 | 114,300 | 131,700 |

| Indiana | 18,200 | 16,900 | 111,300 | 128,300 |

| Iowa | 6,700 | 6,300 | 41,100 | 47,400 |

| Kansas | 5,300 | 4,900 | 32,500 | 37,400 |

| Kentucky | 13,000 | 12,200 | 79,800 | 92,000 |

| Louisiana | 10,100 | 9,400 | 62,000 | 71,500 |

| Maine | 2,000 | 1,900 | 12,400 | 14,300 |

| Maryland | 14,200 | 13,300 | 87,300 | 100,600 |

| Massachusetts | 13,800 | 12,900 | 84,900 | 97,900 |

| Michigan | 24,000 | 22,400 | 147,100 | 169,500 |

| Minnesota | 11,900 | 11,200 | 73,300 | 84,400 |

| Mississippi | 8,000 | 7,400 | 48,800 | 56,200 |

| Missouri | 10,000 | 9,400 | 61,500 | 70,800 |

| Montana | 1,700 | 1,500 | 10,200 | 11,700 |

| Nebraska | 4,200 | 3,900 | 25,900 | 29,800 |

| Nevada | 6,200 | 5,800 | 38,200 | 44,000 |

| New Hampshire | 1,600 | 1,500 | 10,000 | 11,500 |

| New Jersey | 17,600 | 16,400 | 107,800 | 124,200 |

| New Mexico | 3,900 | 3,600 | 23,600 | 27,200 |

| New York | 46,400 | 43,300 | 284,700 | 328,000 |

| North Carolina | 30,900 | 28,900 | 189,700 | 218,600 |

| North Dakota | 1,200 | 1,100 | 7,200 | 8,300 |

| Ohio | 19,200 | 17,900 | 117,700 | 135,600 |

| Oklahoma | 7,600 | 7,100 | 46,800 | 54,000 |

| Oregon | 8,900 | 8,300 | 54,500 | 62,800 |

| Pennsylvania | 19,000 | 17,700 | 116,300 | 134,000 |

| Rhode Island | 1,900 | 1,800 | 11,900 | 13,700 |

| South Carolina | 10,300 | 9,600 | 63,400 | 73,000 |

| South Dakota | 1,600 | 1,500 | 10,100 | 11,600 |

| Tennessee | 13,800 | 12,800 | 84,400 | 97,200 |

| Texas | 83,700 | 78,200 | 513,600 | 591,800 |

| Utah | 4,500 | 4,200 | 27,500 | 31,700 |

| Vermont | 1,300 | 1,300 | 8,200 | 9,500 |

| Virginia | 14,500 | 13,500 | 89,000 | 102,600 |

| Washington | 14,600 | 13,600 | 89,400 | 103,000 |

| West Virginia | 4,100 | 3,800 | 25,000 | 28,800 |

| Wisconsin | 10,100 | 9,400 | 62,000 | 71,400 |

| Wyoming | 800 | 800 | 4,900 | 5,700 |

| Total | 750,000 | 700,000 | 4,600,000 | 5,300,000 |