- Home

- Federal Housing Spending Is Poorly Match...

Chart Book: Federal Housing Spending Is Poorly Matched to Need

Tilt Toward Well-Off Homeowners Leaves Struggling Low-Income Renters Without Help

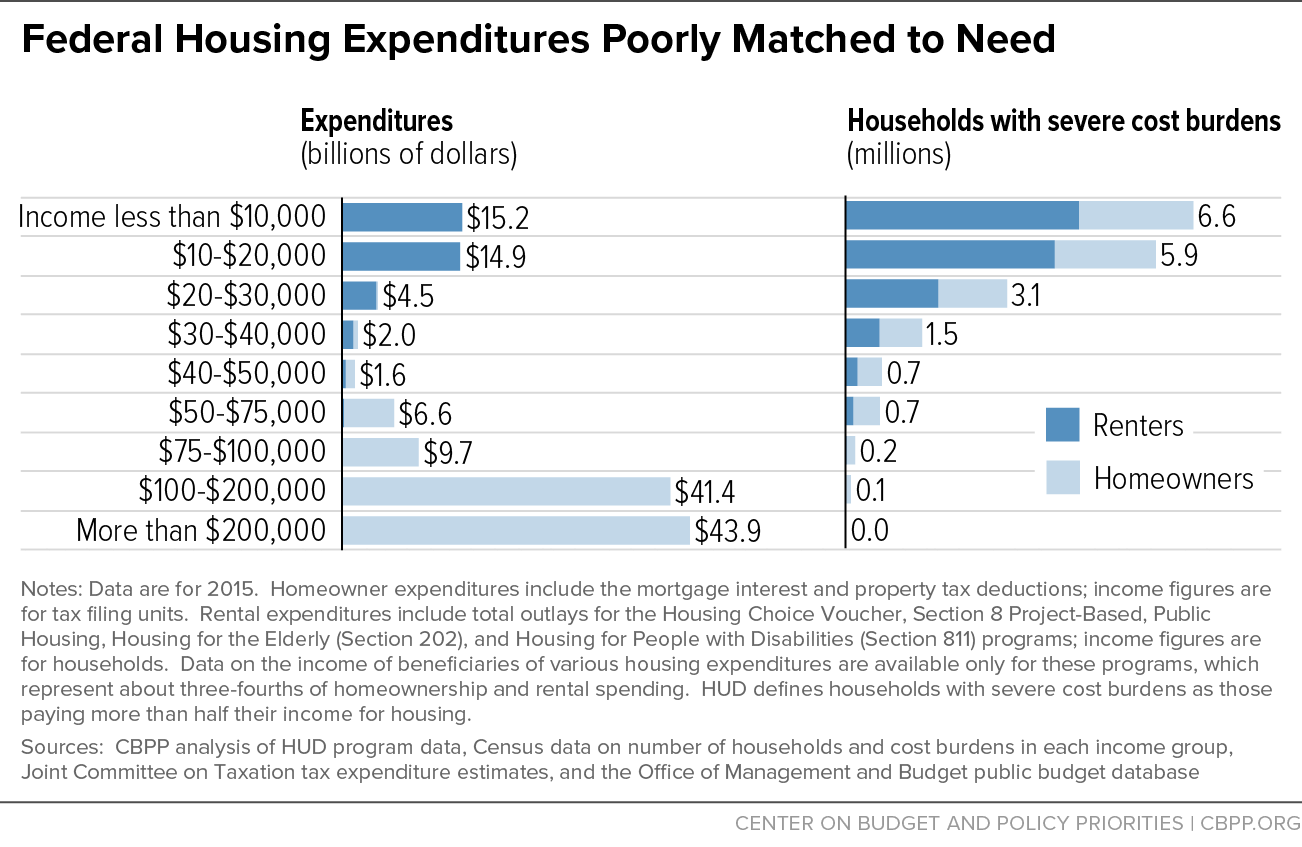

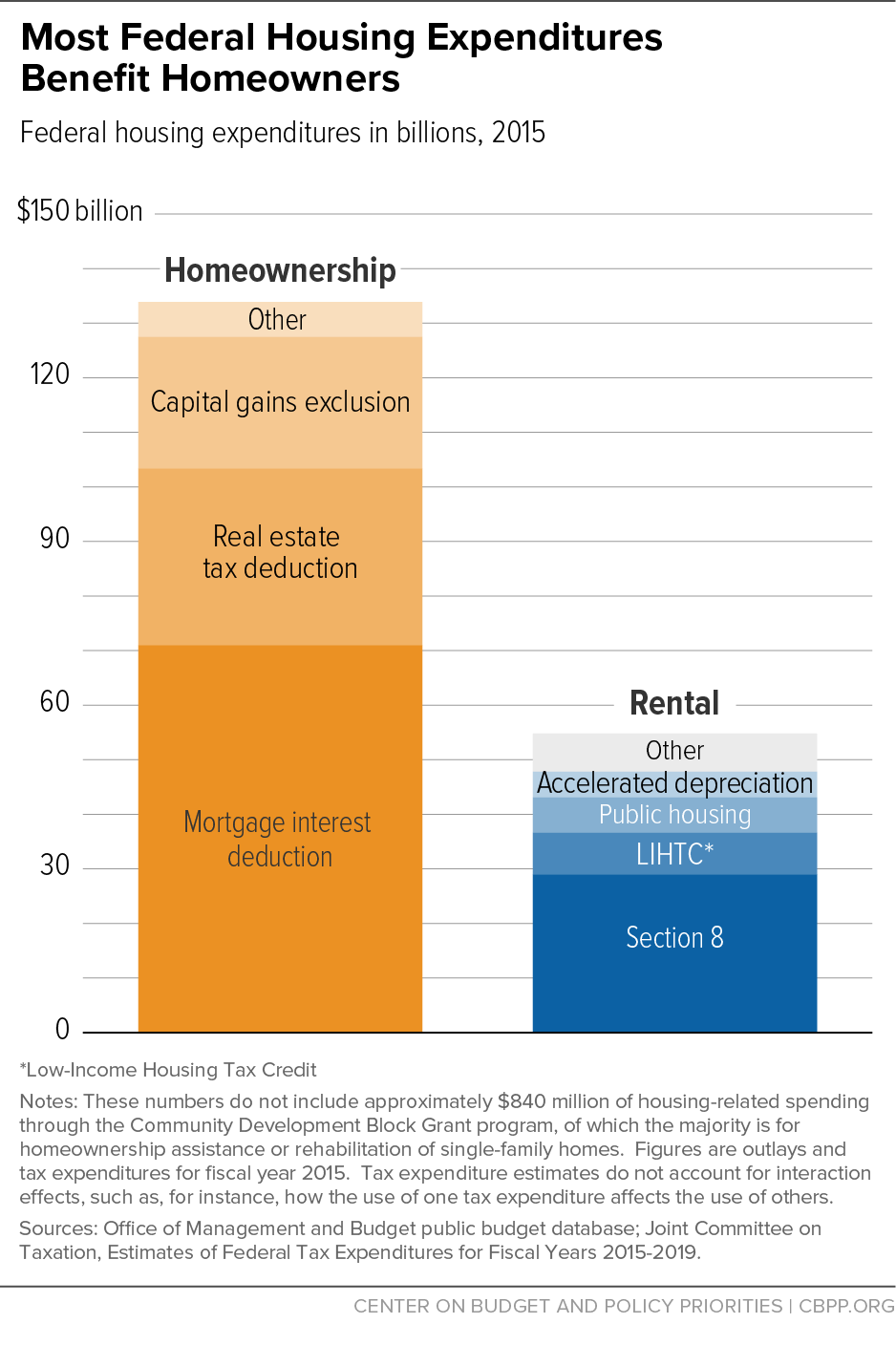

The federal government spent $190 billion in 2015 to help Americans buy or rent homes, but little of that spending went to the families who struggle the most to afford housing. As the charts below show, federal housing expenditures are unbalanced in two respects: they target a disproportionate share of subsidies on higher-income households and they favor homeownership over renting. Lower-income renters are far likelier than homeowners or higher-income renters to pay very high shares of their income for housing and to experience problems such as homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding. Federal rental assistance is highly effective at helping these vulnerable families, but rental assistance programs are deeply underfunded and as a result reach only about one in four eligible households.

- Federal Housing Spending Disproportionately Targets Higher-Income Households

- Federal Housing Policy Favors Owning over Renting

- Housing Needs Among Renters Are Growing

- Poor Renters Have Greatest Need for Housing Assistance

- Federal Rental Assistance Helps the Lowest-Income People Afford Housing, but Funding Limitations Keep It from Reaching Most Families in Need

Part I: Federal Housing Spending Disproportionately Targets Higher-Income Households

Federal housing expenditures favor higher-income households. Most homeownership expenditures go to the top fifth of households by income. More than four-fifths of the value of the mortgage interest and property tax deductions goes to households with incomes of more than $100,000, and more than two-fifths goes to families with incomes above $200,000, according to estimates by the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation.

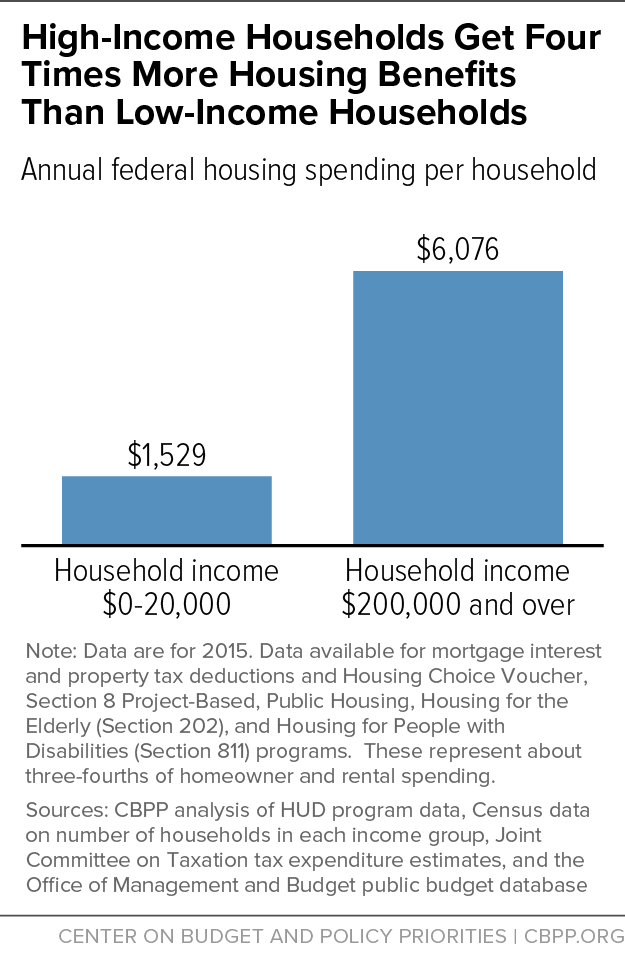

Overall, about 60 percent of federal housing spending for which income data are available (counting both tax expenditures and program spending) benefits households with incomes above $100,000. The 7 million households with incomes of $200,000 or more receive a larger share of such spending than the more than 50 million households with incomes of $50,000 or less, even though lower-income families are far more likely to struggle to afford housing.

In 2015, the most recent year for which complete data are available, households with incomes of $200,000 or more received an average housing benefit of $6,076 — about four times the average benefit of $1,529 received by households with incomes below $20,000. It is difficult to see the policy purpose served by providing such large benefits to higher-income households, who in most cases could afford to purchase a home without subsidies.

Part II: Federal Housing Policy Favors Owning Over Renting

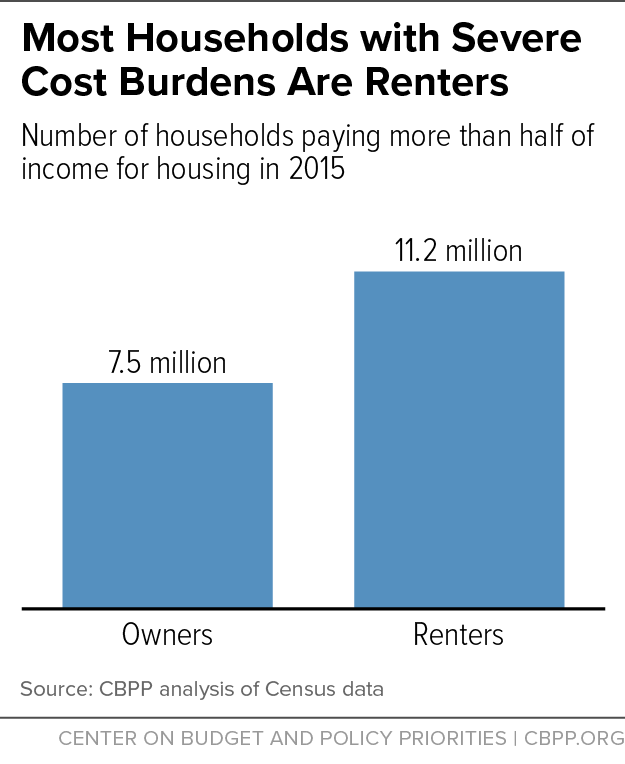

In addition, federal housing expenditures are heavily targeted on homeowners, even though many Americans — and the majority of those with severe housing needs — rent their homes. Renters account for 36 percent of the nation’s households and 60 percent of those paying more than half of their income for housing, not including doubled up and homeless families and individuals, who in most cases would rent but lack the means to do so.

Less than 30 percent of federal housing spending in 2015 went to renters, however. Owners received more than 70 percent of federal housing subsidies, despite making up less than two-thirds of all households and just 40 percent of those with severe housing cost burdens.

Part III: Housing Needs Among Renters Are Growing

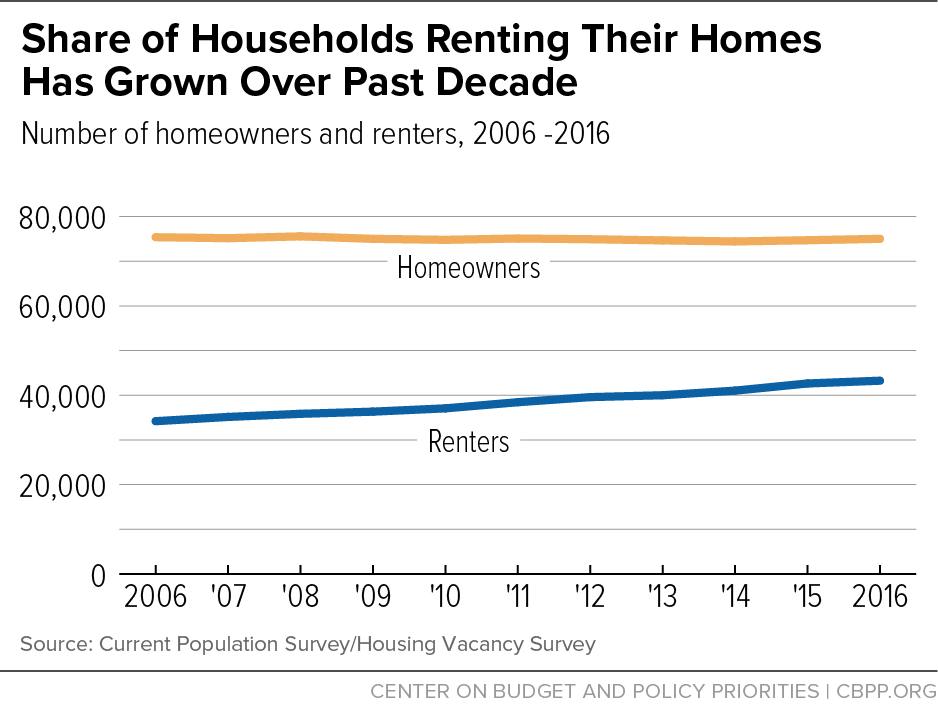

This imbalance has grown in recent years as the number and share of renters who have difficulty affording housing have risen. Since 2006, the number of renter households has grown by nearly 9 million, while the number of homeowner households has remained almost unchanged. As a result, the percentage of households that rent has grown by six percentage points, the most rapid such surge in more than 50 years. Demographic and economic trends make a reversal of this trend in the next several decades unlikely, and there is a good chance the renter share of the population will continue to grow.

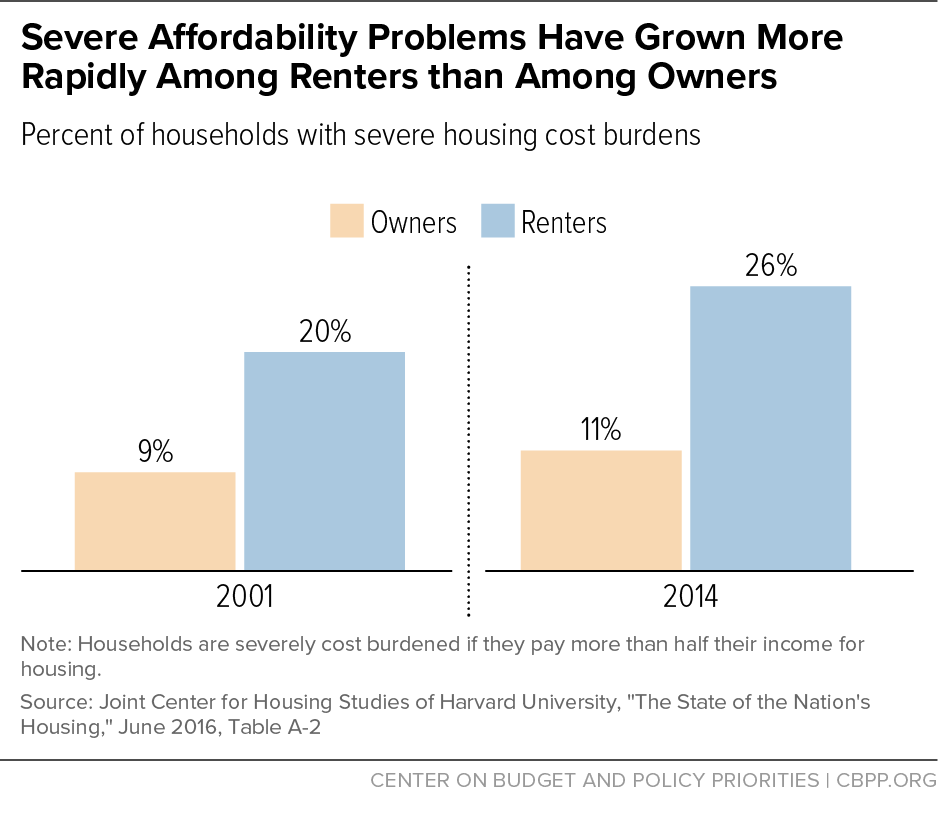

The share of families struggling to afford housing has grown in recent years among both owners and renters, but the increase among renters has been much larger. In 2001, renters were already more than twice as likely as owners to pay more than half their income for housing. By 2014, this gap had widened considerably. Among lower-income households, renters are more likely than homeowners to have very high cost burdens, and this gap has grown over time.

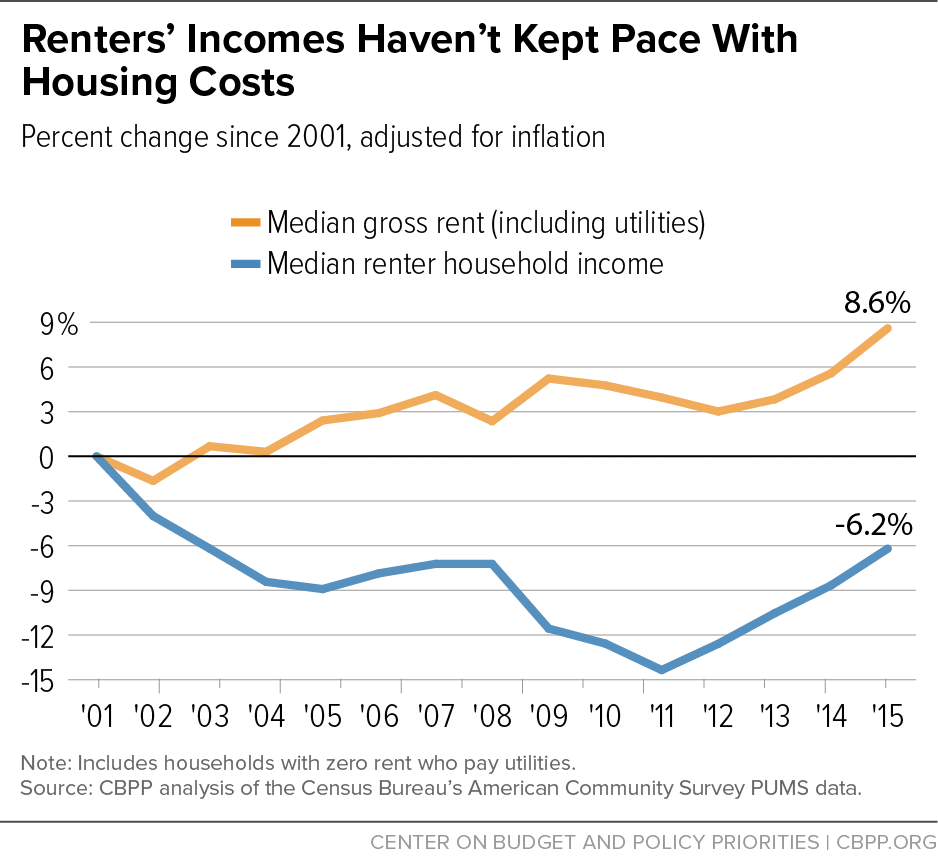

The growth in rental affordability problems reflects a rising gap between rents and incomes. Median renter household income fell sharply during the 2001 and 2007-2009 recessions and has only partly recovered. Rents, on the other hand, stagnated briefly during the downturns but are now growing substantially faster than overall inflation.

Part IV: Poor Renters Have Greatest Need for Housing Assistance

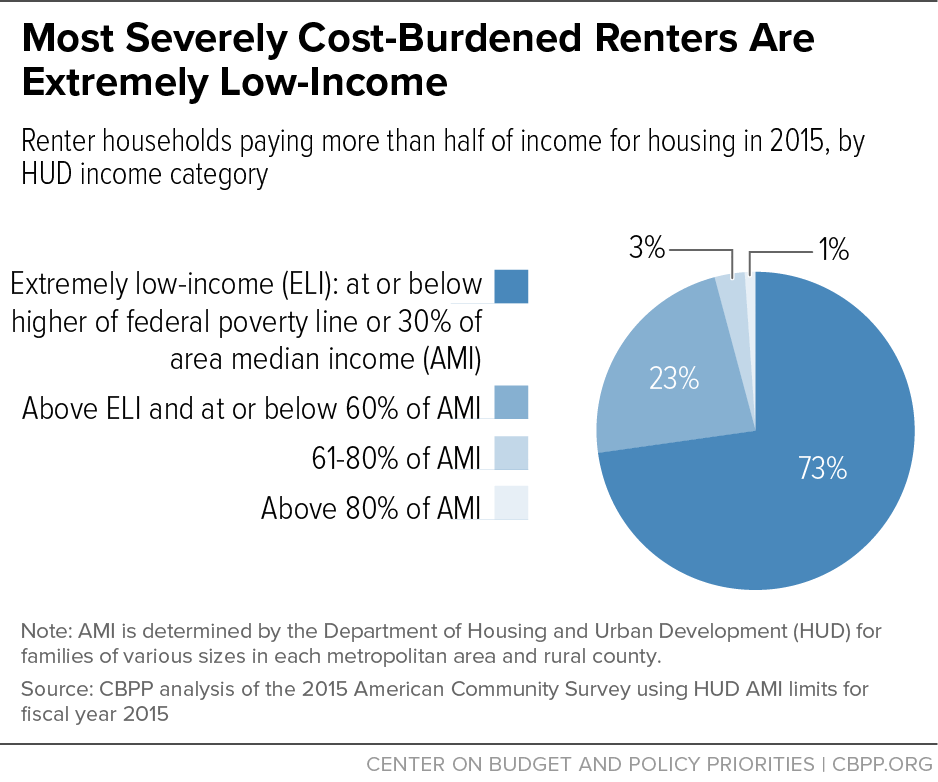

Among renters, high housing cost burdens are heavily concentrated among the lowest-income families. A large majority of renter households that pay more than half of their income for housing costs have what the federal government terms “extremely low incomes,” meaning their incomes are at or below the higher of the federal poverty line or 30 percent of the local median income. Only 4 percent of renters with severe burdens have incomes above 60 percent of median. The lowest-income households are also more likely to experience other serious housing problems, including severely inadequate housing, overcrowding, homelessness, and frequent moves.

Part V: Federal Rental Assistance Helps the Lowest-Income People Afford Housing but Funding Limitations Keep It from Reaching Most Families in Need

Federal rental assistance programs such as Housing Choice Vouchers, Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance, and public housing help more than 5 million of the neediest low-income households afford housing. About 70 percent of these households have incomes below 30 percent of median income, and most are elderly people, people with disabilities, and working poor families with children.

Rental assistance programs are highly effective in assisting the poorest families. For example, housing vouchers have been shown to sharply reduce homelessness and housing instability among families with children. Vouchers provided to homeless families also cut foster care placements (which are often triggered by parents’ inability to afford suitable housing) by more than half, greatly reduced moves from one school to another, and cut rates of alcohol dependence, psychological distress, and domestic violence victimization among the adults with whom the children lived.

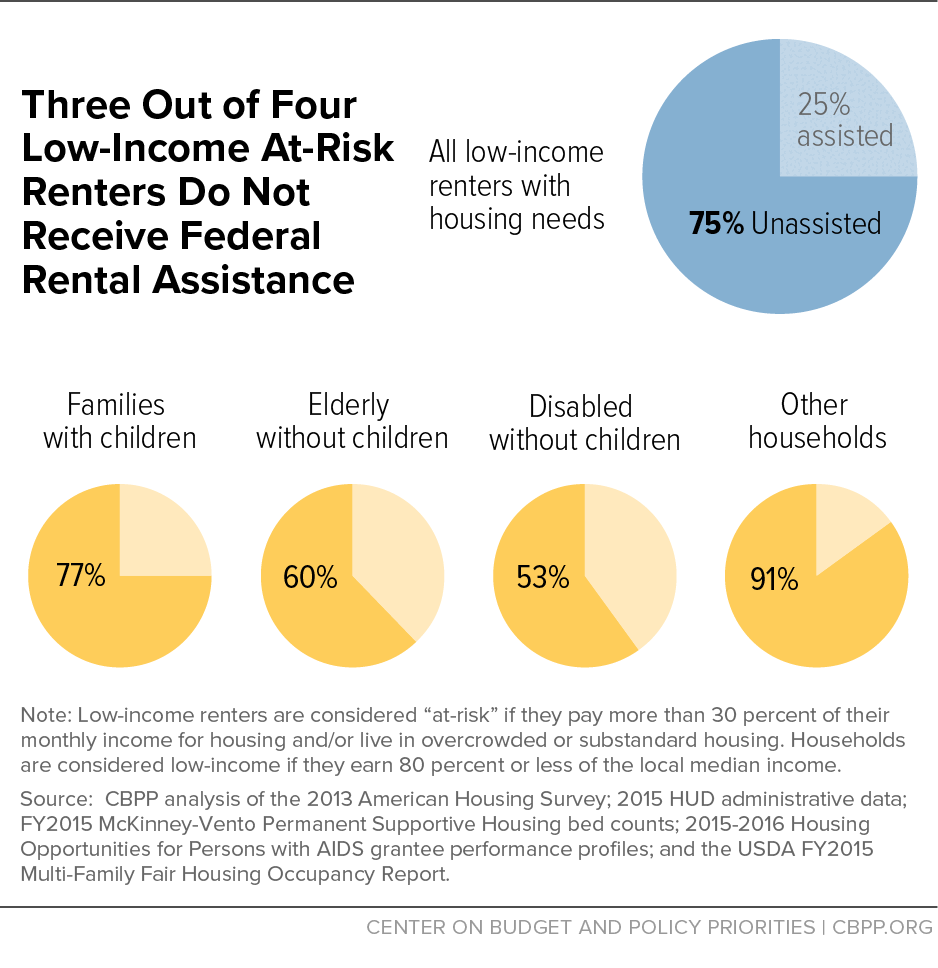

Due to funding limitations, however, rental assistance programs reach only a fraction of needy renters. Only about one in four low-income families eligible for rental assistance receives it, and waiting lists for assistance are long in most parts of the country.

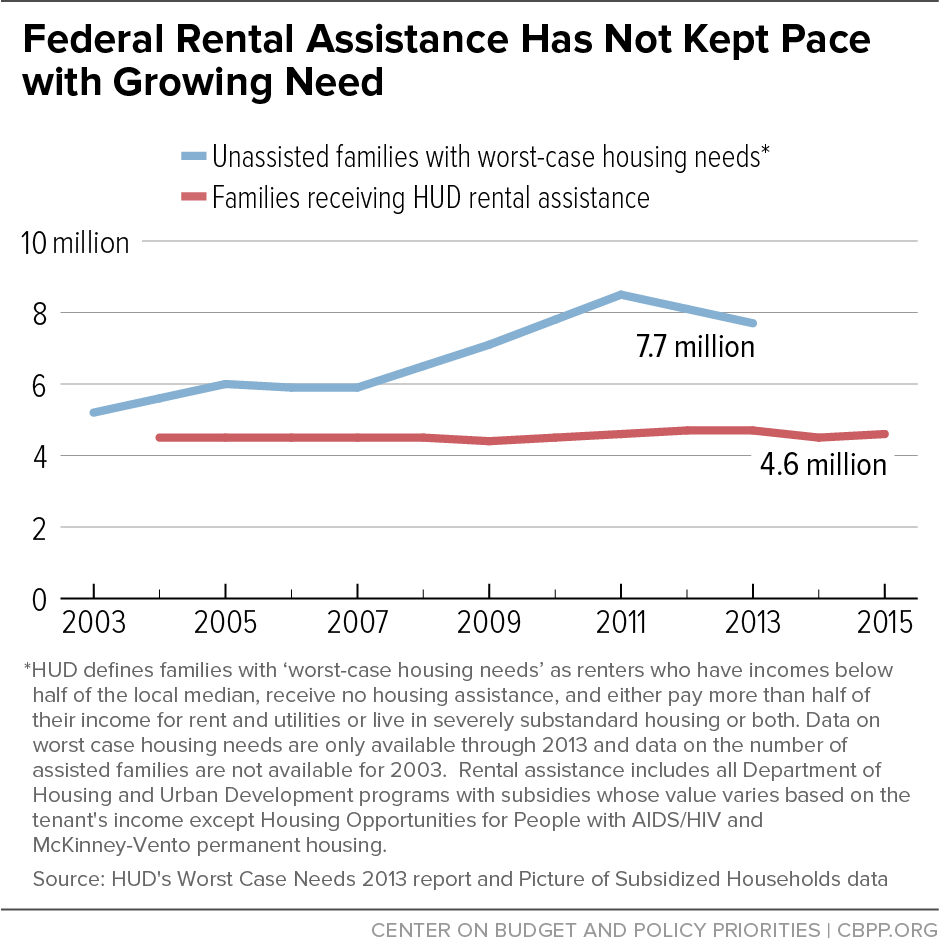

The shortfall in rental assistance has increased significantly over the last decade, as the number of families struggling to afford rental costs has grown, but the number of families receiving rental assistance has not kept pace.