BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Rental Assistance in Recovery Legislation Needed to Protect Children From Hardship and Help Build a More Equitable Future

The COVID-19 crisis increased housing instability for millions of renters and further exposed the inadequacy of the country’s housing safety net, particularly for families with children. As policymakers consider recovery legislation, a top priority should be stronger, more equitable supports for children, including expanding vouchers to a larger share of families in need. Addressing the housing instability that families with low incomes faced even before the pandemic can create opportunity for all children and build toward a more equitable future.

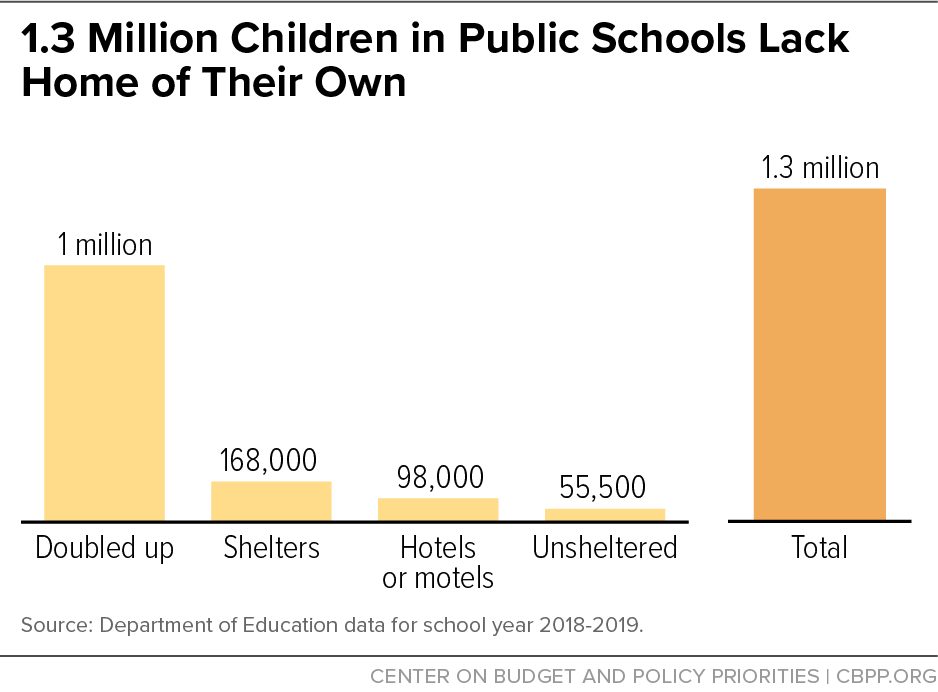

At the end of March 2021, renters who live with children were more than twice as likely to not be caught up on rent, compared to adults not living with children. But even before the pandemic, nearly 8 million children in low-income families faced housing affordability challenges, and more than 1.3 million children experienced homelessness at some point during the 2018-2019 school year.

More than half (53 percent) of all families with children experiencing homelessness on a single night in January 2020 were Black, reflecting a long history of discrimination in housing, employment, and beyond that has led to Black people and other people of color being more likely to rent their homes, to pay more than half of their incomes on rent, and to experience homelessness.

A broad body of research links homelessness, housing instability, overcrowding, and poverty to adverse effects on children’s health, development, and education. This includes cognitive and mental health issues, asthma, physical assaults, and difficulties in school.

Rigorous research shows that the Housing Choice Voucher program, which enables families to rent private-market housing for about 30 percent of their income, reduces homelessness, housing instability, overcrowding, and poverty and has far-reaching implications for other aspects of children’s lives. For example, children whose families are homeless and receive vouchers to rent housing are less likely to be placed in foster care or to experience sleep disruptions and behavioral problems than a control group. They are also likelier to exhibit positive social behaviors such as offering to help others or treating younger children kindly.

Vouchers can also reduce how frequently children change schools, which is particularly important for students with disabilities who receive special education services. Vouchers improve test scores for some groups of children, and teenagers had higher earnings as adults (relative to a control group) for each additional year their family used a voucher or lived in public housing, researchers have also found. By lowering rental costs, vouchers also enable people with low incomes to spend more on other basic needs like food and medicine, as well as on goods and services that enrich their children’s development, including additional health and educational resources for children with disabilities.

Vouchers have major additional benefits when they enable families to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods if they choose. A rigorous study found that children whose families used vouchers to move from high- to low-poverty neighborhoods — which often have better-resourced schools — had substantially higher adult earnings and rates of college attendance than similar children whose families stayed in neighborhoods that have higher rates of poverty and receive fewer investments.

Despite the proven successes, just 1 in 4 eligible families receive any type of federal rental assistance due to funding limitations. With recovery legislation that they’ll soon consider, policymakers have an unprecedented opportunity to expand the voucher program, thereby reducing the number of children living in shelters or motels, on the street, or in overcrowded homes and increasing access to stable housing in neighborhoods that families choose.

Providing vouchers to all who are eligible, as President Biden proposed during his campaign, could cut the child poverty rate by a third, moving 3.4 million children above the poverty line and lifting 1 million out of deep poverty, according to one study. Poverty would fall most for children of color, particularly non-Latino Black and Latino children.

President Biden’s request for 200,000 new vouchers as part of the 2022 budget — a proposal Congress should accept — and the inclusion of targeted programs to expand housing supply in the American Jobs Plan are important steps but will not fully address the need. In communities outside large coastal cities, the supply of housing is often adequate, but the costs are unaffordable to families with low incomes. Moreover, supply investments generally don’t result in housing that’s affordable to the families with children that are at the highest risk of losing their home or already experiencing homelessness.

Rental assistance is essential to make both new and existing rental housing affordable, and policymakers should use upcoming recovery legislation to provide vouchers to many additional people, including more of the millions of children who live every day in unsafe or overcrowded conditions or are at risk of eviction.