SNAP Works for America’s Children

End Notes

[1] Steven Carlson is a research analyst who previously directed the Office of Policy Support at the Agriculture Department’s Food and Nutrition Service. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the views of the Agriculture Department.

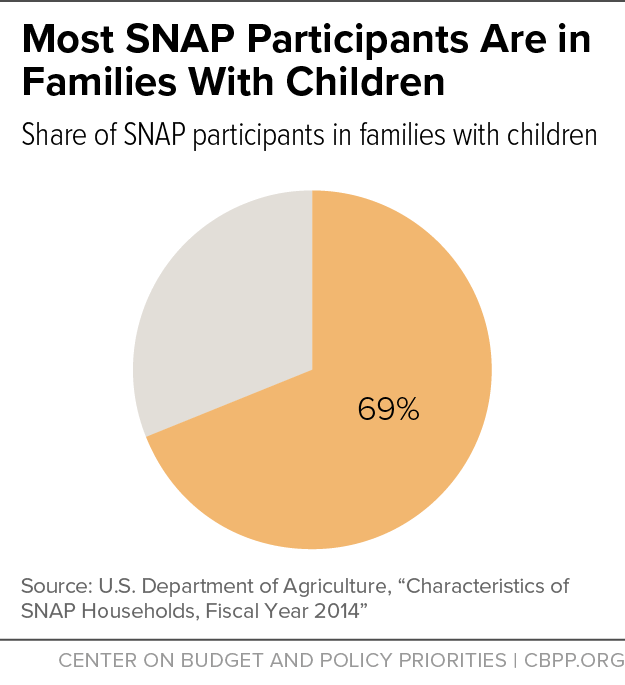

[2] The number of children projected to be served in 2016 and value of SNAP benefits provided to children are estimated by multiplying the Congressional Budget Office’s baseline estimates of total SNAP participation in 2016 (44.5 million) and total SNAP benefits ($67.7 billion) by the share of children among SNAP participants and the pro-rated share of benefits for children in 2014, the most current data available (both about 44 percent). See https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/51312-2016-03-SNAP1.pdf for CBO estimates. In total, households with children received about 67 percent of SNAP benefits in 2014, which would equal about $45 billion in 2016.

[3] See, for example, Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, and Greg Duncan, “The Effects of Poverty on Children,” The Future of Children, 7(2), 1997, www.princeton.edu/futureofchildren/publications/docs/07_02_03.pdf.

[4] John T. Cook and Deborah A. Frank, “Food Security, Poverty, and Human Development in the United States,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136(1), 193-209, 2008, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1196/annals.1425.001/epdf.

[5] Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2016), “From Best Practice to Breakthrough Impacts,” May 2016, http://46y5eh11fhgw3ve3ytpwxt9r.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/HCDC_From_Best_Practices_to_Breakthrough_Impacts.pdf.

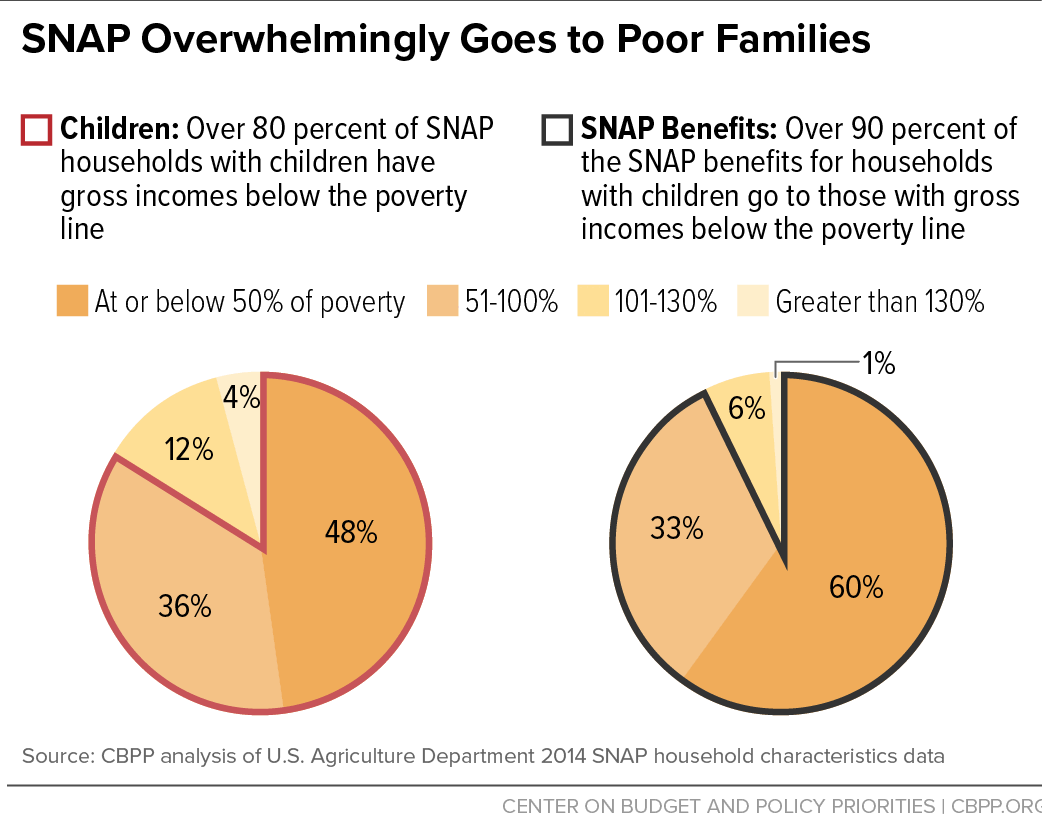

[6] See, for example, Patricia Anderson, Kristin Butcher, and Diane Schanzenbach, “Changes in Safety Net Use During the Great Recession,” American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 105(5): 161–165, 2015, http://www.sesp.northwestern.edu/docs/publications/1064188605560bfd3a080d6.pdf. These researchers focus on SNAP, the Earned Income Tax Credit, Unemployment Insurance, and cash welfare from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program and conclude that “for households below the poverty line, SNAP benefits dominate the other programs.” Although the analysis does not focus specifically on families with children, its conclusions are relevant since nearly half of all SNAP households include children and two-thirds of all participants live in families with children.

[7] The poverty and food security statistics reported in this paper refer to calendar years; all other SNAP statistics refer to fiscal years unless otherwise noted. See Kelsey Farson Gray and Shivani Kochhar, “Characteristics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Households: Fiscal Year 2014,” prepared for the Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, December 2015, www.fns.usda.gov/snap/characteristics-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-households-fiscal-year-2014.

[8] Bernadette D. Proctor, Jessica L. Semega, and Melissa A. Kollar, “Income and Poverty in the United States: 2015,” U.S. Census Bureau, September 2016, http://www.census.gov/library/publications/2016/demo/p60-256.html; and Alisha Coleman-Jensen et al., “Household Food Security in the United States in 2015,” Economic Research Service, USDA, September 2016, http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err215.aspx.

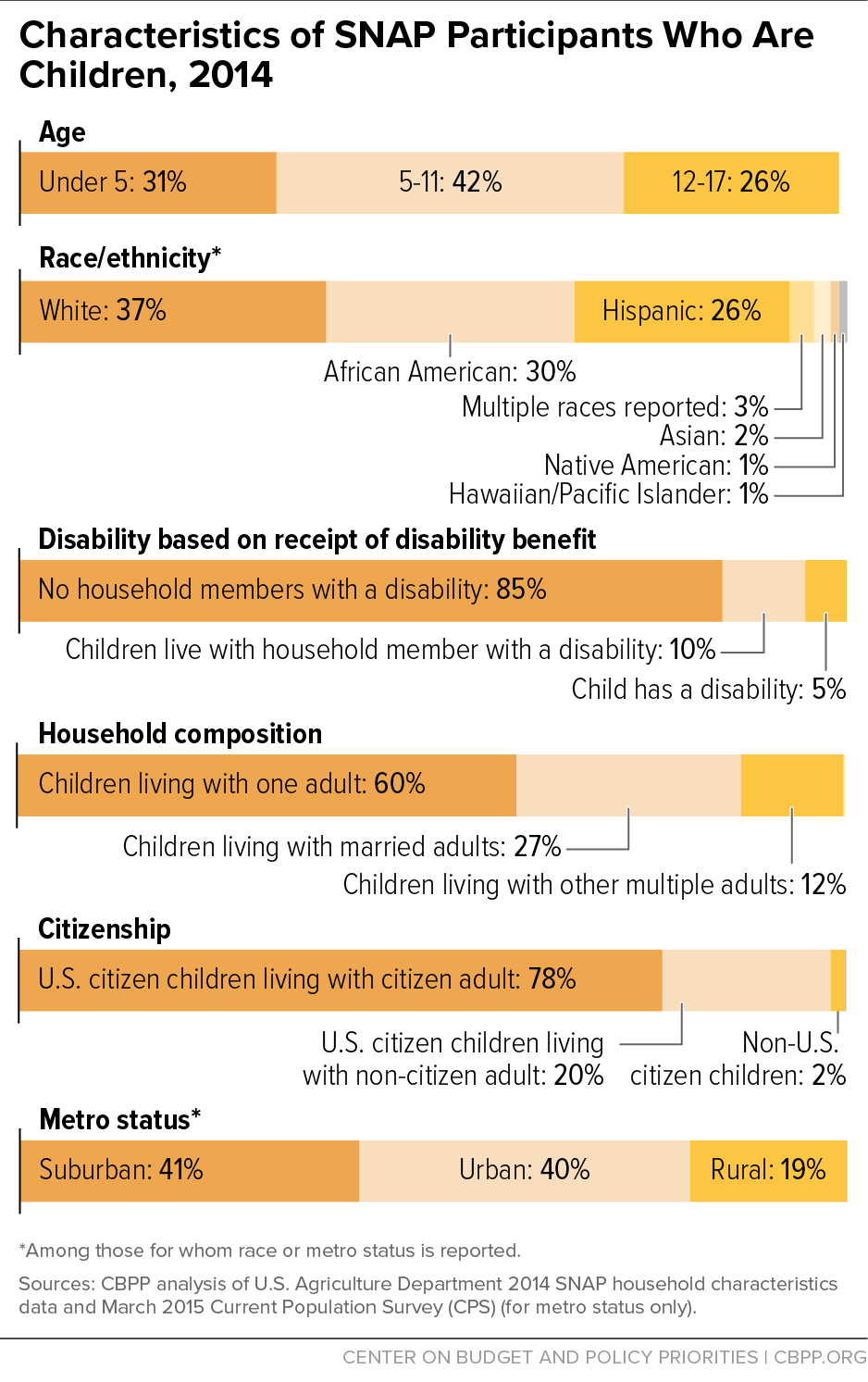

[9] Esa Eslami, “Trends in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation Rates: Fiscal Year 2010 to Fiscal Year 2014,” prepared for the Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, June 2016, http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/trends-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-participation-rates-fiscal-year-2010-fiscal-year. Because of the challenges of combining multiple data sources to simulate program eligibility and participation, estimates of participation rates among eligible children can exceed 100 percent. While it is unlikely that the program reaches every eligible child every month, it is fair to conclude that participation among eligible children is very high.

[10] These figures reflect the fact that households with non-citizen members are more likely to be low-income than other U.S. households. More than one in four low-income children live with a non-citizen, according to Census Bureau data. All undocumented immigrants and many legal immigrant adults are ineligible for SNAP.

[11] Kelsey Farson Gray and Shivani Kochhar, “Characteristics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Households: Fiscal Year 2014,” prepared for the Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, December 2015, table A.2, www.fns.usda.gov/characteristics-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-households-fiscal-year-2014.

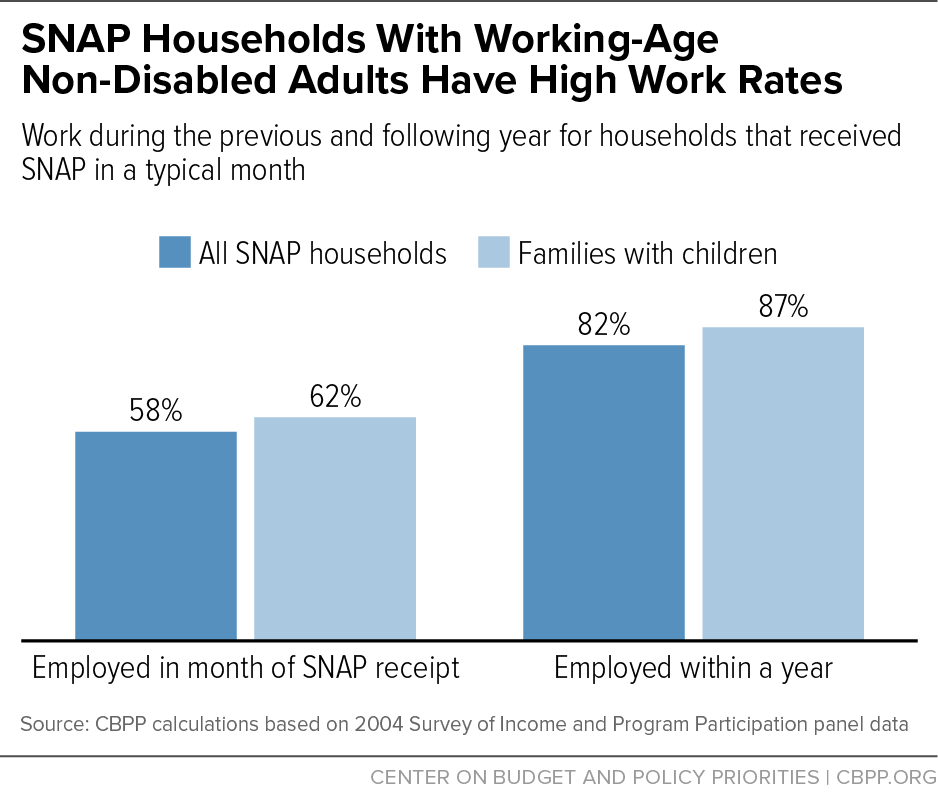

[12] Dorothy Rosenbaum, “The Relationship between SNAP and Work Among Low-Income Households,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities,” January 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/1-29-13fa.pdf. The figures are based on data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) for the mid-2000s, before the recent recession, but preliminary analysis finds that they declined only modestly during the recession. For this analysis SNAP household members are considered to be working-age if they are age 18 through 59 and are disabled if they receive a disability-based benefit, such as Social Security Disability Insurance or Supplemental Security Income (SSI).

[13] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “Welfare Indicators and Risk Factors: Fourteenth Report to Congress,” September 22, 2015, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/116161/FINAL%20Fourteenth%20Report%20-%20FINAL%209%2022%2015.pdf.

[14] SNAP’s disability definition is stringent; a person must be receiving a benefit such as Social Security Disability Insurance benefits, SSI, or veterans’ benefits based on total disability to be considered disabled. As a result, these figures likely understate the degree that SNAP children and their family members experience a disability; some may have less severe disabilities while others may not yet have received a disability determination from another program.

[15] Joshua Leftin, et al., “Dynamics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation from 2008 to 2012,” prepared for the Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, December 2014, www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/ops/Dynamics2008-2012.pdf.

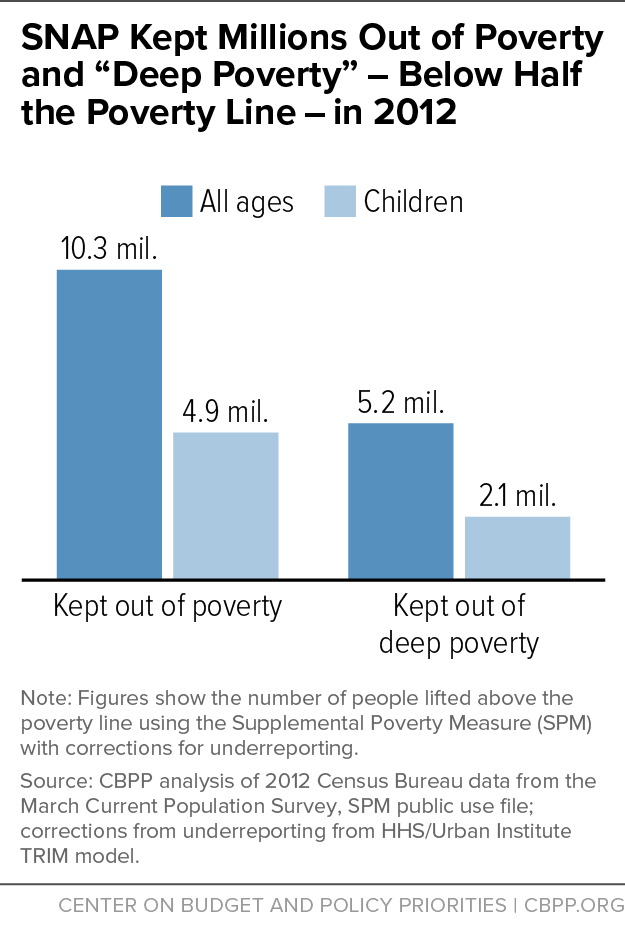

[16] Arloc Sherman and Danilo Trisi, “Safety Net More Effective Against Poverty than Previously Thought,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 6, 2015, www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/safety-net-more-effective-against-poverty-than-previously-thought. Figures for 2012 include the Recovery Act’s temporary SNAP benefit increase which has since ended; current figures may be lower. More recent data from the Census Bureau, also based on the Supplemental Poverty Measure but without the correction for underreporting of benefits, affirms the continued anti-poverty effectiveness of SNAP. These data show that SNAP benefits lifted at least 2.1 million children out of poverty, and more than 1.3 million children above half of the poverty line, in 2014. See Kathleen Short, “Current Population Reports: The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2014.” U.S. Census Bureau, September 2015, www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p60-254.pdf. Although the estimated impacts in 2014 are less than those in 2012, it would be incorrect to conclude that SNAP was less effective in reducing poverty among children. The difference instead illustrates how important it is to correct for underreported benefits: the uncorrected estimates miss billions of dollars from government benefit programs and substantially understate the safety net’s anti-poverty effectiveness.

[17] The standard measure of poverty — the poverty rate — is simply the proportion of persons living in poverty. Additional measures of the depth and severity of poverty provide a more complete picture of SNAP’s importance for the well-being of low-income families by capturing increases in income among the poor even if the increases are not large enough to lift them out of poverty. Depth of poverty is the difference between a family’s income and the poverty line; the measure of severity is similar but gives more emphasis to families with the lowest incomes, under the logic that they are the highest priority for poverty reduction.

[18] Laura Tiehen, Dean Jolliffe, and Timothy Smeeding, “The Effect of SNAP on Poverty” in Judith Bartfeld, Craig Gundersen, Timothy Smeeding and James Ziliak (eds.), SNAP Matters: How Food Stamps Affect Health and Well-Being, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016. Depth of poverty is measured by the poverty gap, the average distance between a family’s income and the poverty threshold, where the average is formed over the entire population (so that the non-poor are counted as having zero poverty gap). Severity of poverty is measured as the average of the squared poverty gaps.

[19] Laura Tiehen, Dean Jolliffe, and Craig Gundersen, “Alleviating Poverty in the United States: The Critical Role of SNAP Benefits,” Economic Research Service, USDA, April 2012, www.ers.usda.gov/media/478608/err132_1_.pdf.

[20] Luke Shaefer and Kathryn Edin, “Rising Extreme Poverty in the United States and the Response of Federal Means-Tested Transfer Programs,” Social Service Review, 87(2): 250-268, 2013.

[21] Michael Linden, “Turning Point: The Long Term Effects of Recession-Induced Child Poverty,” First Focus, May 2009, https://firstfocus.org/resources/report/turning-point-long-term-effects-recession-induced-child-poverty/ and William Schneider, Jane Waldfogel, and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, “The Great Recession and Behavior Problems in 9-Year Old Children,” Developmental Psychology, 51(11): 1615-1629, November 2015.

[22] The most current data available on children’s food security are presented in Alisha Coleman-Jensen, Matthew Rabbitt, Christian Gregory, and Anita Singh, “Household Food Security in the United States in 2015,” Economic Research Service, USDA, September 2016, http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err215.aspx.

[23] See Alisha Coleman-Jensen, William McFall, and Mark Nord, “Food Insecurity in Households with Children: Prevalence, Severity, and Household Characteristics, 2010–11,” Economic Research Service, USDA, 2013, http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/eib-economic-information-bulletin/eib113.aspx for a comprehensive catalog of the substantial and growing body of research on the associations between children’s health, development, and well-being and measures of food security.

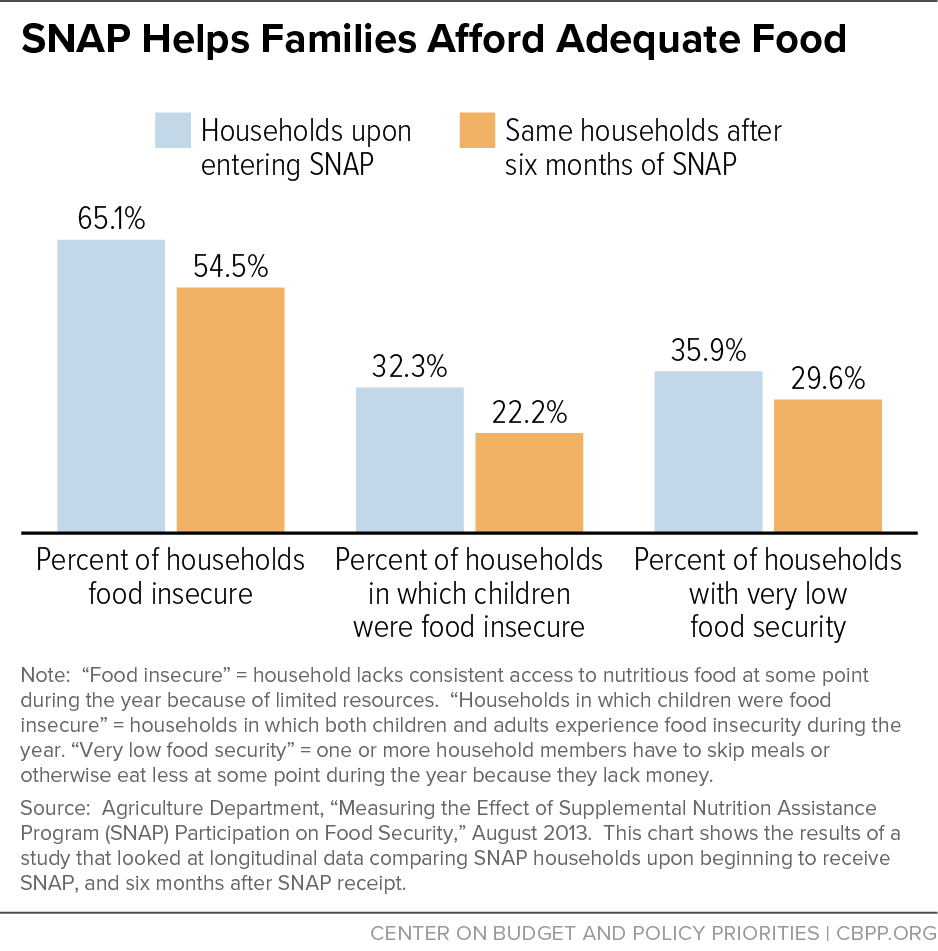

[24] For a more complete summary of this emerging research see Craig Gundersen, and James P. Ziliak, “Childhood Food Insecurity in the US: Trends, Causes, and Policy Options,” The Future of Children 24(2), 2014, www.aap-oc.org/wp-content/uploads/large-files/Food%20Insecurity%20Research%20Report%20Fall%202014.pdf. This study finds that children living with a disabled adult, for example, are almost three times as likely to experience very low food security as children who don’t; the risk of food insecurity among children rises by at least 50 percent when mothers are moderately to severely depressed; and the children at most risk of very low food security are disproportionately raised in immigrant families.

[25] James Mabli and Julie Worthington, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation and Child Food Security,” Pediatrics, 133(4), 2014, pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2014/02/25/peds.2013-2823.abstract and Yiran Li, et al., “Child Food Insecurity and the Food Stamp Program: What a Difference Monthly Data Make,” Social Services Review, 88(2), 2014, uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=ukcpr_papers.

[26] The demonstration initially provided a monthly benefit of $60 in the summer of 2012 and then compared the relative effectiveness of a smaller benefit ($30) in the summers of 2013 and 2014. The results suggested that both increases produced similar improvement in the most severe form of food insecurity among children. The study also tested delivering SNAP benefits or benefits through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). In each group, and for the combined two groups, the $60 benefit reduced the prevalence of very low food security among children by about one-third, and there was not a statistically significant difference in the reduction of food insecurity or very low food security among children between the SNAP and WIC groups. See Ann Collins, et al., “Summer Electronic Benefits Transfer for Children (SEBTC) Demonstration: Summary Report,” prepared for the Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, May 2016, www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/ops/sebtcfinalreport.pdf.

[27] Stephanie Ettinger de Cuba, et al., “Diluting the Dose: Cuts to SNAP Benefits Increased Food Insecurity Following the Great Recession,” Children’s HealthWatch, September 2015, www.childrenshealthwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/FINAL-Diluting-the-Dose-for-web-.pdf. The findings of this study are consistent with another study that found that the number of SNAP households with very low food security increased by 16.5 percent between 2009 and 2011, when the real value of the temporary benefit increase declined due to food price inflation. See Mark Nord, “Effects of the Decline in the Real Value of SNAP Benefits From 2009 to 2011,” USDA Economic Research Service Report Number 151, August 2013, http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/1155211/err151.pdf

[28] Tatiana Andreyeva, Amanda S. Tripp, and Marlene B. Schwartz, “Dietary Quality of Americans by Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation Status: A Systematic Review,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(4), 2015, www.uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/1-s2_0-S0749379715002263-main.pdf.

[29] Patricia M. Anderson and Kristin F. Butcher, “The Relationships Among SNAP Benefits, Grocery Spending, Diet Quality, and the Adequacy of Low-Income Families’ Resources,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 14, 2016, www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/6-14-16fa.pdf.

[30] Douglas Almond, Hillary Hoynes, and Diane Schanzenbach, “Inside the War on Poverty: The Impact of Food Stamps on Birth Outcomes,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(2), 2011, www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1162/REST_a_00089. It is important to note that much has changed since the initial introduction of the Food Stamp Program, including the introduction and growth of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and Medicaid. A similar study using the county rollout in California also found that the introduction of food stamps was associated with a reduction in birth weight, which was driven particularly by first births among teens and by changes for Los Angeles County. See Janet Currie and Enrico Moretti, “Did the Introduction of Food Stamps Affect Birth Outcomes in California?” in Harold Pollack, Making Americans Healthier: Social and Economic Policy as Health Policy, Russell Sage Foundation, 2008, www.princeton.edu/~jcurrie/publications/RS_foodstamps.pdf.

[31] Children’s HealthWatch is a nonpartisan network of pediatricians, public health researchers, and children’s health and policy experts that has collected data on more than 42,000 infants and toddlers from families facing economic hardship. These researchers survey the caregivers of children under four visiting emergency departments and clinics at hospitals in five cities: Baltimore, Little Rock, Boston, Philadelphia, and Minneapolis. The survey is supplemented with detailed medical and sociodemographic data from administrative records.

[32] Katherine M. Joyce, et al., “Household Hardships, Public Programs, and Their Associations with the Health and Development of Very Young Children: Insights from Children’s HealthWatch,” Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, 3(1), 2012, www.childrenshealthwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/KJ_JARC_2012.pdf and Stephanie Ettinger de Cuba, et al., “The SNAP Vaccine: Boosting Children’s Health,” Children’s HealthWatch, February 2012, www.childrenshealthwatch.org/publication/the-snap-vaccine-boosting-childrens-health-2/.

[33] See, for example, Allison Bovell, et al., “Making SNAP Work for Families Leaving Poverty,” Children’s HealthWatch, November 2014, www.childrenshealthwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/FINALPhilly-Food-to-web3.pdf and Stephanie Ettinger de Cuba, et al., “Punishing Hard Work: The Unintended Consequences of Cutting SNAP Benefits,” Children’s HealthWatch, December 2013, www.childrenshealthwatch.org/publication/punishing-hard-work-unintended-consequences-cutting-snap-benefits/.

[34] Chloe East, “The Effect of Food Stamps on Children's Health: Evidence from Immigrants’ Changing Eligibility,” March 2016, http://cneast.weebly.com/uploads/8/9/9/7/8997263/east_jmp.pdf. While immigrants are a select and relatively more disadvantaged group of SNAP participants, children of immigrants account for about a quarter of all children and one-third of children in poverty. Welfare reform eliminated SNAP eligibility for most immigrant families in 1996, but subsequent federal legislation gradually restored eligibility between 1998 and 2003. These changes in eligibility allow for a relatively strong test of the impact of SNAP on children's health.

[35] Alternatively, body weight may influence the decision to participate in SNAP. Although this possibility has not yet been tested among children, a recent study of adult women found a strong and statistically significant relationship between obesity and the propensity to participate in SNAP. Joanna P. McEwan, Aaron Smith, and Julian M. Alston, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Energy Balance, and Weight Gain,” Food Policy, 61, 103–120, 2016, www.researchgate.net/publication/297698608_The_Supplemental_Nutrition_Assistance_Program_energy_balance_and_weight_gain.

[36] For example, one study concluded that SNAP participation is associated with an increase in obesity among young girls, a reduction among young boys, and has no effect on older children (see Diane Gibson, “Long-Term Food Stamp Program Participation Is Differentially Related to Overweight in Young Girls and Boys,” The Journal of Nutrition, 134(2), 2004, jn.nutrition.org/content/134/2/372.full). Another concluded that SNAP is associated with decreases in obesity among most children (see Maximilian Schmeiser, “The Impact of Long‐Term Participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program on Child Obesity,” Health Economics, 21(4), 2012, 386-404). A third analysis found no evidence of a consistent relationship between childhood obesity and participation in SNAP (see Michele Ver Ploeg, et al., “US Food Assistance Programs and Trends in Children’s Weight,” International Journal of Pediatric Obesity, 3(1), 2008, 22-30). And finally, a recent study cautions that the effect of participating in more than one food assistance program may be greater than the sum of the individual programs and estimates that simultaneous participation in SNAP, school lunch, and school breakfast reduces adolescent BMI by nearly 12 percent (see Manan Roy, Daniel L. Millimet, and Rusty Tchernis, “Federal Nutrition Programs and Childhood Obesity: Inside the Black Box,” Review of Economics of the Household, 10(1), 2012: 1-38, www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/51971/1/668768452.pdf).

[37] Brent Kreider, et al., “Identifying the Effects of SNAP (Food Stamps) on Child Health Outcomes When Participation Is Endogenous and Misreported,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 107(499), 2012: 958-975, http://batten.virginia.edu/sites/default/files/research/attachments/JASA_KPGJ_online(1).pdf.

[38] For a brief summary of the underlying research, see Meredith Hickson et al., “Too Hungry to Learn: Food Insecurity and School Readiness” and “Feeding Our Human Capital: Food Insecurity and Tomorrow’s Workforce,” Children’s HealthWatch, September 2013, www.childrenshealthwatch.org/publication/too-hungry-to-learn/ and www.childrenshealthwatch.org/publication/feeding-our-human-capital-food-insecurity-and-tomorrows-workforce/.

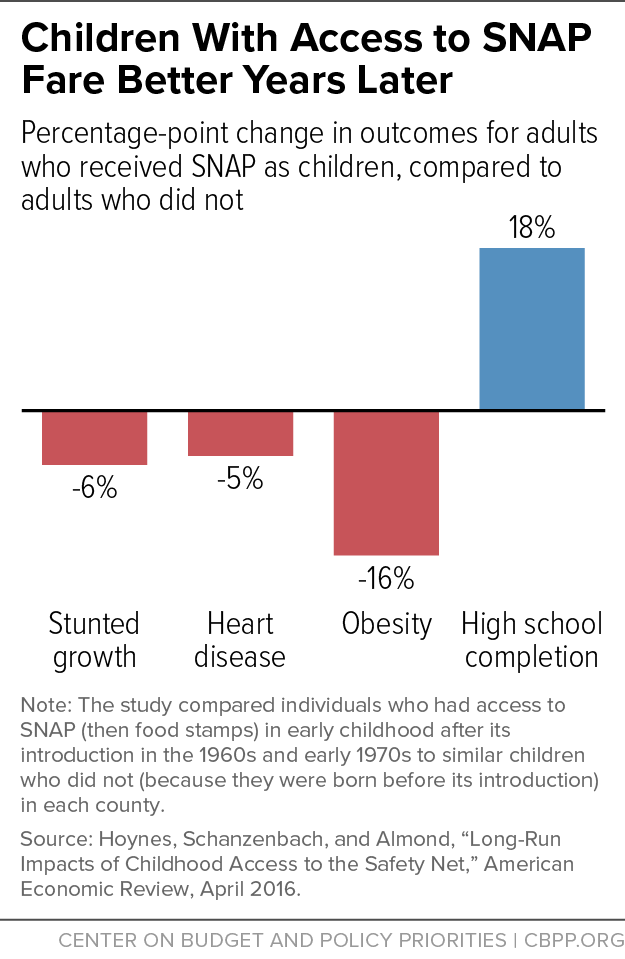

[39] Edward Frongillo, Diana F. Jyoti, and Sonya J. Jones, “Food Stamp Program Participation is Associated with Better Academic Learning among School Children,” Journal of Nutrition, 136(4): 2006, 1077-80, http://jn.nutrition.org/content/136/4/1077.full and Hilary Hoynes, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Douglas Almond, “Long-Run Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net,” American Economic Review, 106(4): 2016, 903–934. There is also some limited evidence that the time elapsed since the issuance of SNAP benefits within a month can also affect test scores (see Anna Gassman-Pines, and Laura Bellows, “SNAP Recency and Educational Outcomes,” 2015, papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2701380).

[40] Hilary Hoynes, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Douglas Almond, “Long-Run Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net,” American Economic Review, 106(4): 2016, 903–934.

[41] Judith Bartfeld, “SNAP and the School Meal Programs,” in Judith Bartfeld, Craig Gundersen, Timothy Smeeding, and James Ziliak (eds.), SNAP Matters: How Food Stamps Affect Health and Well-Being, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016.