- Inicio

- House Bill Makes New Round Of Damaging C...

House Bill Makes New Round of Damaging Cuts in Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education

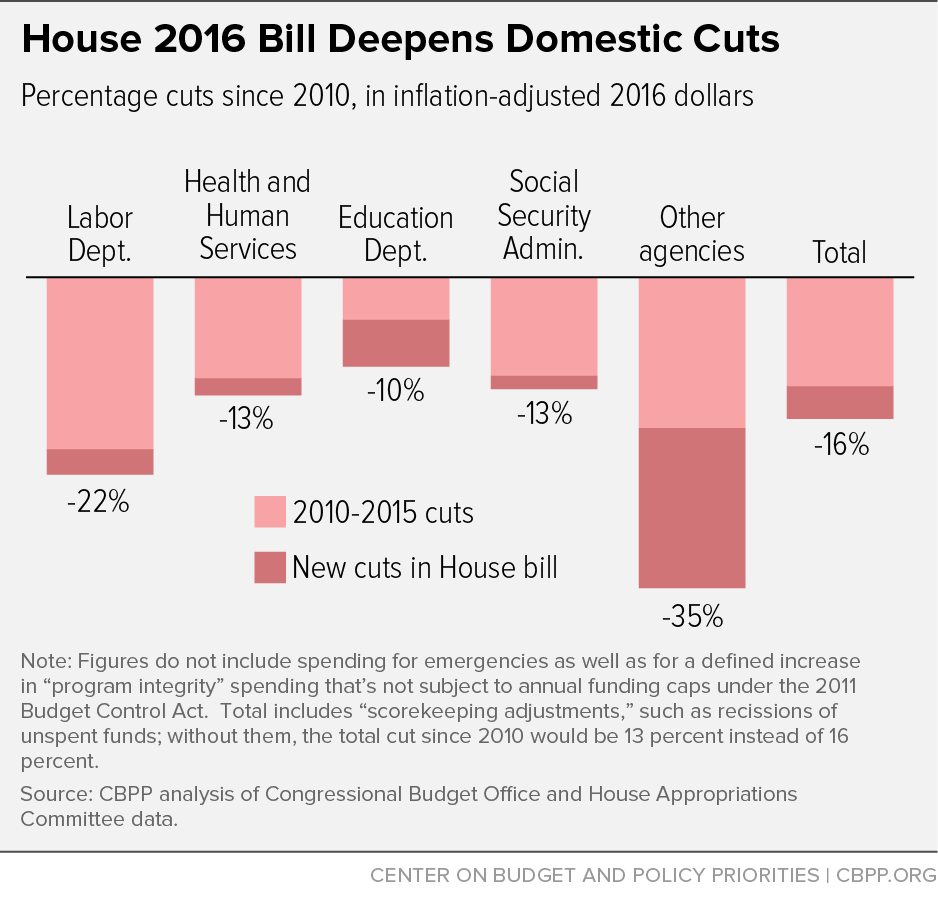

The 2016 Labor, Health and Human Services (HHS), and Education appropriations bill approved by the House Appropriations Committee provides $3.7 billion less than the year before, with the largest cuts coming in education and health. The bill eliminates or deeply cuts several major programs that aid local schools, ends grants for expanding preschool programs, ends assistance to family planning clinics, and cuts the agency that administers Medicare and the health insurance marketplaces by one-sixth, for example. Coming on top of several previous rounds of cuts, the bill’s overall funding level is $29 billion — or 16 percent — below the 2010 level, after adjusting for inflation.[1] (See Figure 1.) In several areas the cumulative cut is even larger: K-12 education and job training, for example, are each about one-fifth below 2010 levels.

The new cuts reflect the tight caps on annual appropriations imposed by the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA), as further reduced by sequestration. But they also reflect a decision by the committee’s Republican majority to make the Labor, HHS, and Education bill one of their lowest priorities. In allocating funding among the 12 appropriations bills, the committee majority targeted the Labor-HHS-Education bill for the largest dollar cut by far and the second-largest percentage cut.

The bill does include badly needed increases in areas such as medical research, special education, and Head Start, which its authors cite as evidence that some high-priority needs can be addressed despite the caps and sequestration. Most of the increases, however, are unrealistic, as the bill offsets those increases with highly controversial cuts that have little chance of passing the Senate and virtually no chance of becoming law.

In addition to funding cuts, the House bill includes language that would prohibit HHS from implementing most of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), effectively blocking most of the assistance that helps low- and moderate-income people gain health coverage. It also contains other damaging policy riders, such as language blocking efforts to protect against conflicts of interest by retirement plan advisers, to bar the worst-performing career colleges from benefiting from federal student aid programs, and to improve the process by which workers vote on whether to be represented by a union.

This bill does indeed reflect a series of choices, but those choices are neither necessary nor beneficial.In defending this and other recent appropriations bills, committee Republicans have said that the legislation reflects difficult but necessary choices. This Labor-HHS-Education appropriations bill does indeed reflect a series of choices, but those choices are neither necessary nor beneficial.

Indeed, the first choice that congressional Republicans made this year was not to use the budget resolution process to develop a plan to create more room under the sequestration-lowered BCA caps, paid for with alternate deficit reduction, as the President and congressional Democrats have urged. Instead, the budget resolution, adopted on party-line votes, calls for sticking strictly to the current cap for non-defense appropriations. (Meanwhile, the Republican majority decided to evade the BCA cap for defense by designating additional expenses as being for Overseas Contingency Operations and thus outside the caps, regardless of their actual purpose.)[2]

In the end, there is no good way to apportion an additional $3.7 billion in cuts within this bill, on top of the cuts made over the past five years. And the increases it provides to select programs are a mirage in the absence of a deal to raise the caps.

| TABLE 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| House Labor-HHS-Education Appropriations Overview (in billions of dollars) | |||||||

| 2010 enacted | 2015 enacted | 2016 | Percent change, adjusted for inflation | ||||

| current dollars | 2016 dollars | current dollars | 2016 dollars | House bill | 2010 to 2016 |

2015 to 2016 |

|

| Dept. of Labor | 13.5 | 15.1 | 11.9 | 12.2 | 11.7 | -22.5% | -3.6% |

| Dept. of Health and Human Services | 73.2 | 82.0 | 71.2 | 72.6 | 70.9 | -13.4% | -2.2% |

| Dept. of Education | 64.0 | 71.7 | 66.9 | 68.2 | 64.4 | -10.2% | -5.6% |

| Social Security Admin. | 11.1 | 12.4 | 10.8 | 11.0 | 10.8 | -12.7% | -1.8% |

| Other Independent Agencies | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.8 | -35.4% | -21.0% |

| Scorekeeping adjustmentsa | -1.3 | -1.5 | -6.3 | -6.4 | -6.6 | 348.5% | 3.3% |

| Bill total | 163.1 | 182.5 | 156.8 | 159.8 | 153.1 | -16.1% | -4.3% |

| Program integrity (outside Budget Control Act caps) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 173.4% | -1.9% |

a Scorekeeping adjustments are mostly changes in mandatory programs and rescissions. Note: Totals do not include emergencies and program integrity spending eligible for a cap adjustment under the 2011 Budget Control Act. Figures for the 2016 House bill represent the measure as approved by committee.

Sources: CBPP analysis of Congressional Budget Office and House Appropriations Committee data

Department of Education

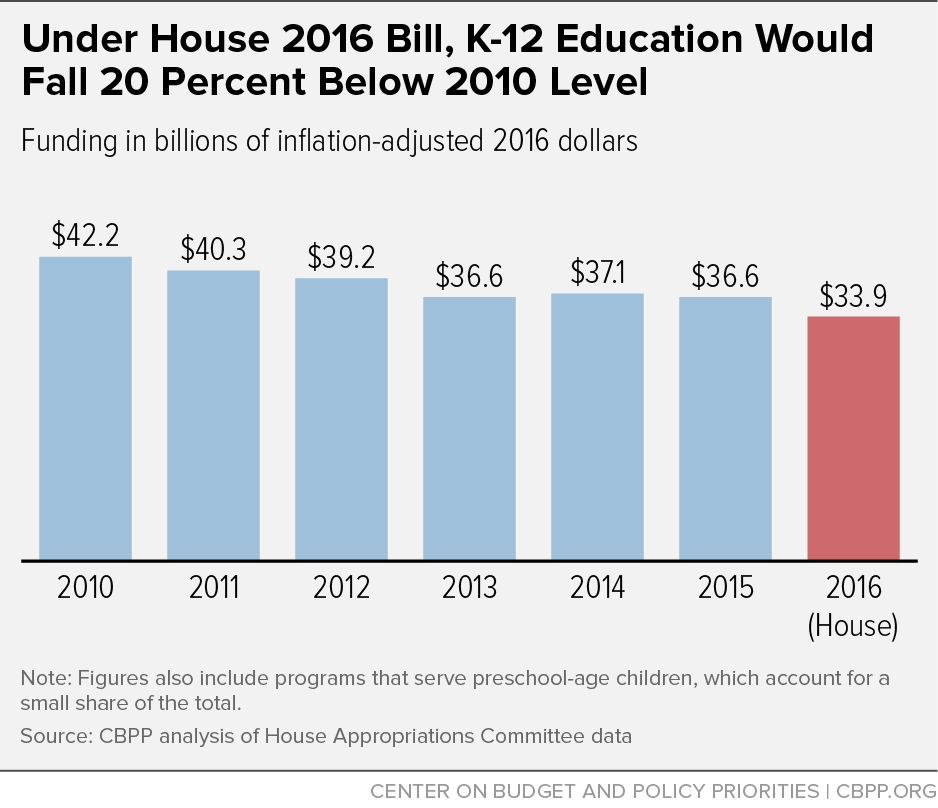

Education programs take the largest overall reduction ($2.5 billion) under the bill. Well over half of these cuts come in elementary, secondary, and preschool education, total funding for which would fall to one-fifth below the 2010 level, after adjusting for inflation. (See Figure 2.) Federal funding for K-12 education has dropped in recent years even as state support has been tightly constrained.[3]

For the largest elementary and secondary education assistance program — Title I grants to school districts to serve disadvantaged students — the bill holds funding at the 2015 level, which is slightly below the 2010 level even before adjusting for inflation. Adjusted for inflation, Title I funding in the bill is 11 percent below 2010.

The bill includes a $502 million increase for grants under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) to support education for children with special needs. This increase will bring special education appropriations back above the 2010 level in nominal terms, though still 7 percent below 2010 after adjusting for inflation. The bill also has a 7 percent increase for the TRIO and GEAR UP programs, which help students from disadvantaged backgrounds prepare for and succeed in higher education.

The bill’s education cuts, however, are several times larger than its increases. The bill eliminates or reduces funding to help turn around poorly performing schools, recruit and train high-quality teachers, improve math and science teaching, and improve school safety (see Appendix for details). It also eliminates grants to develop or expand high-quality preschool programs for children from low- and moderate-income families.

Finally, the bill cuts Pell Grants, which help low- and moderate-income students afford college, by $370 million. This cut likely would not affect the program’s ability to serve all eligible applicants in the upcoming school year. However, the Pell Grant program is expected to face a modest shortfall within the next few years, and the cut could move up the date when that occurs to as early as 2017.[4]

Department of Health and Human Services

The bill cuts HHS by $215 million below the 2015 level, the net result of a series of cuts and increases to various HHS programs.

The most far-reaching cuts involve virtually shutting down most of the Affordable Care Act. The bill prohibits the funds it provides from being used in any way to implement or further the ACA (except for a narrow set of provisions). This prohibition would effectively shut down the federally run health insurance marketplaces and greatly hamper state-run marketplaces, seriously disrupting assistance with premiums and copayments for low- and moderate-income consumers in the marketplaces. It would also effectively block federal funding of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. (See box for details.)

The bill also cuts appropriations by $649 million (about one-sixth) for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which has the lead role in implementing the ACA. The cut seems primarily intended to remove all funding related to the ACA but could also create problems for Medicare operations.

In addition, the bill rescinds all remaining funding from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, which tests innovative service delivery and payment models in Medicare and Medicaid aimed at cutting costs without impairing quality of care or improving quality without raising costs. This one-time rescission of $6.8 billion would actually raise Medicare and Medicaid costs by $37.6 billion over the next ten years because of forgone savings from innovations that would not be tested and implemented — for a net cost of $30.8 billion, according to the Congressional Budget Office.[5]

Other major cuts in the bill include eliminating assistance to family planning programs; abolishing the agency with primary responsibility for research into health care delivery, quality, and safety; and cutting grants for teen pregnancy prevention by more than 90 percent (see Appendix for details).

The bill includes some increases — most notably a $1.1 billion increase for biomedical research at the National Institutes of Health. There is also a $192 million increase for Head Start and increases for some activities within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as well as cuts for other CDC activities such as programs to reduce tobacco use.

Department of Labor

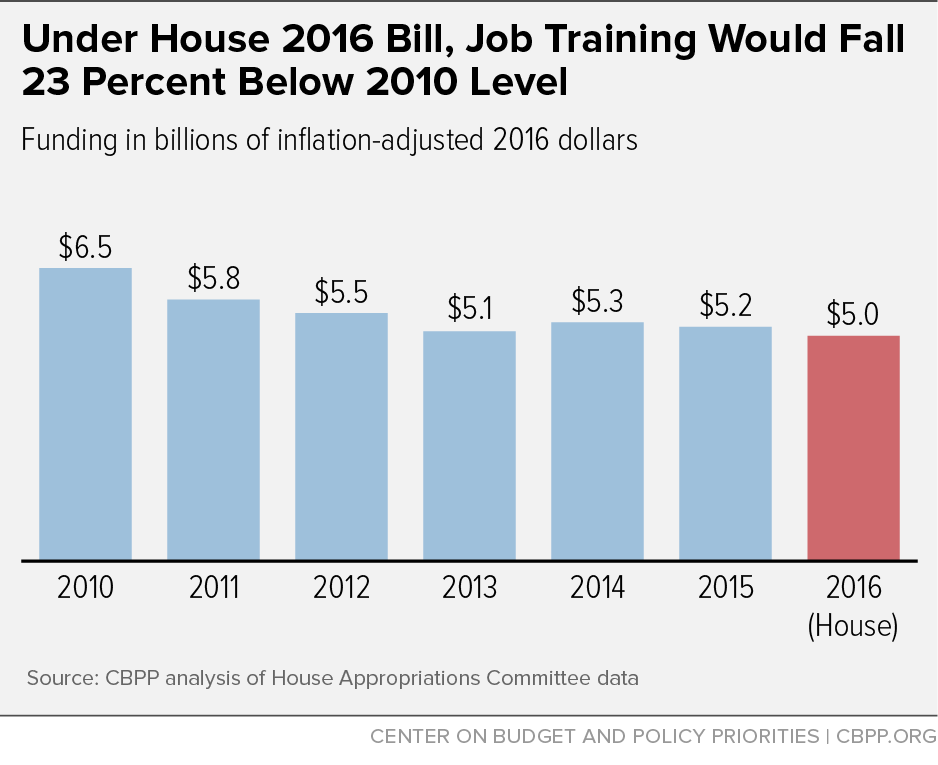

The bill cuts the Department of Labor by $204 million below the 2015 level. The largest cuts come in job training for dislocated workers and in international labor programs to fight child labor and other abuses. The bill also makes smaller but significant cuts in a number of agencies that enforce laws governing minimum wages, overtime, health and safety, and other worker protections.

The new cuts come on top of larger cuts in recent years. In job training, for example, the House bill is 23 percent below the 2010 level after adjusting for inflation. (See Figure 3.)

Related Agencies

The bill funds a number of independent agencies with missions related to the Departments of Labor, HHS, or Education. It cuts by more than one-third the Corporation for National and Community Service, which operates several domestic service programs, including AmeriCorps (to which the cuts are mainly targeted). It also cuts by more than one-fourth the National Labor Relations Board, which investigates complaints of unfair practices in labor-management relations and oversees secret-ballot elections to determine if workers wish to be represented by a union.

For the Social Security Administration (SSA) — by far the largest of the independent agencies the bill covers — the bill freezes funding at 2015 levels. Appropriations for SSA’s operating expenses (excluding additional amounts provided specifically for program integrity) fell by 11 percent between 2010 and 2015, after adjusting for inflation, leading to reduced staff, shortened office hours, and increased waiting time for appointments and telephone assistance, among other problems.[6]

Bill Would Cripple Health Reform Implementation

The House bill prohibits any funds it appropriates from being used “to implement, administer, enforce, or further any provision” of the Affordable Care Act (with certain exceptions related to Medicare payment rates and Medicaid payments for prescription drugs). It also cuts off other funds that might be available for ACA implementation. For example, it prohibits using fees now paid by companies selling insurance on the federal marketplaces to help cover federal marketplace costs, terminates the HHS “nonrecurring expenses fund” (which HHS has used for some ACA-related information technology investments), and rescinds whatever small amounts might remain from mandatory start-up implementation funding in the ACA itself.

Thus, the bill effectively blocks funds for HHS to operate health insurance marketplaces in the 34 states with federally run marketplaces (and in three other states where state marketplaces use the HHS infrastructure). That would shut down this mechanism for people to purchase quality health insurance. It thus would seriously disrupt the availability of federal premium and cost-sharing assistance, which is available only through the marketplaces. This policy stands in stark contrast to the Supreme Court ruling in King v. Burwell, which validated federally run marketplaces by making clear that federal assistance for purchasing health insurance in these marketplaces was legal.

Similarly, the bill would greatly hamper the functioning of state-run marketplaces, as HHS would not be able to provide them with “data hub” services such as helping them verify citizenship and income as required for those seeking marketplace subsidies. Further, the bill would block funding for expansions of Medicaid under the ACA.*

In short, the bill would seriously jeopardize coverage for most of the 16 million people who have already gained health insurance under the ACA and prevent eligible uninsured people from newly enrolling.

The bill also blocks HHS and the Labor Department from enforcing the ACA’s consumer and patient protections. Among other things, these protections prohibit insurers from denying coverage or charging higher premiums because of a person’s health or gender, prohibit annual or lifetime coverage limits, and require insurers to cover preventive care without copayments.

*The Medicaid expansion is subject to the prohibition against using the bill’s funds to implement or further the ACA, because the bill includes a “mandatory appropriation” for Medicaid (although those amounts are not covered by the BCA caps or reflected in the bill’s funding totals).

Appendix

Additional Information on Selected Cuts and Increases in House Bill

Department of Education

The bill reduces appropriations for the Education Department $2.5 billion below the 2015 level. Compared with 2010, the overall cut is $7.3 billion or 10 percent, after adjusting for inflation.

Elementary and Secondary Education Assistance. Support for elementary, secondary, and preschool education would face a more than $2 billion cut under the bill relative to 2015 levels, leaving these programs 20 percent below their inflation-adjusted 2010 levels. While some of these education programs would receive increases relative to 2015 (such as grants under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) or flat funding (such as Title I grants), others would be cut sharply, as discussed below:

- School Improvement Grants. The bill eliminates funding for School Improvement Grants, which received $506 million in 2015. These grants provide funding to state education agencies, which then make competitive sub-grants to local school districts with the greatest need to boost achievement among students in low-performing schools.

- Teacher Quality State Grants. The bill cuts these grants, which provide competitive and formula grant funding to states to improve the quality and performance of teachers and students, by $668 million relative to the 2015 level. The grants support monetary incentives for high-quality teachers, reductions in class sizes, recruitment of teachers with expertise in special needs areas, professional development, and other activities. Funding for these grants is already significantly below the 2010 level and would fall to roughly half its inflation-adjusted 2010 amount under the House bill.

- Preschool Development Grants. The bill eliminates funding for these grants, which received $250 million per year in 2014 and 2015. In doing so, it reverses a decision made by Congress two years ago to make a modest investment in expanding preschool programs for low- and moderate-income families because of strong evidence that early learning is important to school readiness and achievement. These grants go to states for use in high-need communities, to build preschool program infrastructure and capacity or expand high-quality programs.

- Other education programs. The House bill eliminates more than two dozen education programs overall, most of which support elementary and secondary education. Examples include Striving Readers, which supports efforts to improve literacy in high-needs schools; Math-Science Partnerships, which provides formula grants to states to improve the education and professional development of elementary and high school math and science teachers; Investing in Innovation, which makes competitive grants to develop, evaluate, and expand initiatives to improve student achievement; and Safe Schools, which funds projects to reduce violence and improve schools’ safety and learning climate. The savings from eliminating these activities are used to meet the bill’s overall target for cuts, rather than invested in other education programs.

Pell Grants. The House bill cuts $370 million from Pell Grants, which help more than 8 million low- and moderate-income students afford college. The cuts likely would not affect eligibility and benefits for students this year because Pell has a small surplus of carryover funds from previous years. However, by reducing this surplus, the bill might move up to 2017 the point at which a Pell Grant funding gap emerges. Ironically, while the House committee’s report calls Pell Grants’ current path “unsustainable,” its cut to the Pell Grant appropriation would increase the program’s relatively modest future funding gap.

| TABLE 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department of Education Appropriations Overview (in billions of dollars) | |||||||

| 2010 enacted | 2015 enacted | 2016 | Percent change, adjusted for inflation | ||||

| current dollars | 2016 dollars | current dollars | 2016 dollars | House bill | 2010 to 2016 | 2015 to 2016 | |

| Department of Education, total | 64.0 | 71.7 | 66.9 | 68.2 | 64.4 | -10.2% | -5.6% |

| All elementary, secondary, & preschool education | 37.7 | 42.2 | 35.9 | 36.6 | 33.9 | -19.6% | -7.5% |

| Title I grants | 14.5 | 16.2 | 14.4 | 14.7 | 14.4 | -11.1% | -1.9% |

| Individuals with Disabilities Education Act state grants | 12.3 | 13.8 | 12.3 | 12.5 | 12.8 | -7.2% | 2.1% |

| Impact Aid | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | -9.1% | -1.2% |

| Improving Teacher Quality State Grants | 2.9 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 1.7 | -49.0% | -29.8% |

| 21st Century Community Learning Centers | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | -11.8% | -1.9% |

| English Language Acquisition | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | -12.1% | -1.9% |

| School Improvement Grants | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | -100.0% | -100.0% |

| All other elementary, secondary, & preschool | 4.2 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 1.8 | -60.6% | -43.8% |

| Career & adult education | 2.0 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | -24.6% | -2.3% |

| Pell Grants | 17.5 | 19.6 | 22.5 | 22.9 | 22.1 | 12.9% | -3.5% |

| Other higher ed. & student financial assistance | 5.2 | 5.8 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.3 | -8.3% | -1.3% |

| Research, management, and all other | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.3 | -28.8% | -12.4% |

Note: Figures do not include emergencies. Minor adjustments have been made where necessary to make the categories comparable across years.

Source: CBPP analysis of House Appropriations Committee data

Department of Health and Human Services

The bill cuts HHS appropriations by $215 million below 2015, bringing the cumulative cut since 2010 to $11.0 billion or 13 percent, after adjusting for inflation.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The bill cuts CMS $649 million below 2015. This agency is responsible for operating Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), as well many aspects of the ACA, including operating and overseeing health insurance marketplaces and implementing the ACA’s consumer protections. The cut below 2015 seems intended to roughly correspond to the amount of appropriated funds expected to be spent on ACA-related activities in 2016. This cut, combined with the bill’s other prohibitions on funding the ACA, would have a devastating effect on ACA implementation.

If all of the bill’s cuts are allocated to the ACA, then funding for non-ACA programs would be frozen, which could hamper Medicare operations. In fact, under the committee bill CMS would have less funding in 2016 than in 2010, before the ACA’s enactment — and that decrease is before adjusting for inflation or the growing numbers of Medicare beneficiaries and claims needing processing.

National Institutes of Health. The bill raises funding for biomedical research at NIH by $1.1 billion. The increase would bring total NIH funding above the 2010 level in nominal terms for the first time in six years. Adjusted for inflation, however, NIH funding would still be 9 percent below 2010.[7]

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The bill provides no funding for AHRQ and includes legislative language abolishing the agency. AHRQ, which undertakes and sponsors research on health care systems and delivery to increase the safety, quality, accessibility, and affordability of health care, received $364 million in 2015. The agency has supported research on topics such as changing hospital practices to reduce health care-associated infections, using health information technology more effectively to improve care, and focusing health care payment systems on quality of care rather than number of procedures. AHRQ also collects and makes available basic data on health care delivery, including the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey — a major source of data on health care utilization, spending, payment sources, and insurance coverage.

The committee argues that the agency’s functions overlap with other HHS agencies, such as NIH and CDC. In reality, however, AHRQ has a distinct focus on health care delivery research, rather than basic biomedical research or public health. Also, while the bill states that other agencies may take on some of AHRQ’s functions if they wish (and if they have the legal authority to do so), it provides no funding for that purpose. It therefore is difficult to see how many of those functions would be preserved — including AHRQ’s statistical surveys and data dissemination.

Family planning. The House bill eliminates all funding for the “Title X” family planning program, which received $286 million in 2015. Begun in 1970, Title X supports public and private non-profit clinics that offer family planning and related preventive health services, such as screenings for cancer and sexually transmitted infections, with charges reduced or eliminated for low-income patients. These clinics served more than 4.5 million patients and helped avert an estimated 870,000 unintended pregnancies in 2013, according to HHS. On average, Title X grants provide about one-fifth of revenue for grantee clinics, providing a key source of funding for maintaining staffing and facilities and supporting services to uninsured patients.

Teen pregnancy prevention. The bill cuts funding from $108 million to $10 million for grants for teen pregnancy prevention (including evaluation). This program makes grants to public and private organizations to replicate programs proven effective and operate demonstration programs to develop additional effective approaches. At the same time, the bill raises funding for a separate teen pregnancy prevention program based on an “abstinence-only” model from $5 million to $10 million.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While the bill includes both cuts and increases at CDC, the net effect is to raise CDC’s overall funding by $155 million. CDC’s total funding would still be 10 percent below 2010 after adjusting for inflation, however.[8]

The increases include $120 million for a new initiative to combat antibiotic-resistant infections, a $50 million increase for programs to reduce prescription drug overdoses, and a $76 million increase for the Strategic National Stockpile of vaccines, drugs, and other supplies to respond to disease outbreaks or bio-terrorist events.

The bill cuts funding for CDC’s tobacco-use reduction programs by more than half (from $216 million to $105 million). These programs include a national media campaign (“Tips from Former Smokers”), support for telephone “quitlines” that help smokers interested in quitting, and funding for state and local tobacco prevention programs. In addition, the bill cuts CDC environmental health programs by $19 million (10 percent relative to 2015, without adjusting for inflation), including eliminating CDC’s program to examine the public health effects of climate change.

Head Start. The bill boosts Head Start by $192 million. Of that increase, $150 million is designated to expand Early Head Start programs (which serve children up to age 3) and partnerships between Early Head Start grantees and child care providers. While this increase matches the Administration’s request for Early Head Start, the bill ignores other Administration proposals for Head Start, such as providing funds to restore the number of funded slots in 2016 to the 2014 level without diminishing quality, or making all Head Start programs full-school-day and full-school-year operations.

Despite the modest Head Start increase, the bill reduces overall funding for early childhood education because it eliminates Preschool Development Grants funded through the Education Department.

| TABLE 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department of Health and Human Services Appropriations Overview (in billions of dollars) |

|||||||

| 2010 enacted | 2015 enacted | 2016 | Percent change, adjusted for inflation | ||||

| current dollars | 2016 dollars | current dollars | 2016 dollars | House bill | 2010 to 2016 |

2015 to 2016 |

|

| Department of Health and Human Services, totala | 73.2 | 82.0 | 71.2 | 72.6 | 70.9 | -13.4% | -2.2% |

| Health Resources & Services Admin. | 7.8 | 8.7 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 5.8 | -33.2% | -6.8% |

| Centers for Disease Control & Prevention | 6.9 | 7.8 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 7.0 | -9.7% | 0.3% |

| Nat’l Institutes of Health | 30.7 | 34.4 | 30.1 | 30.7 | 31.2 | -9.3% | 1.7% |

| Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Admin. | 3.6 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.6 | -9.2% | -1.3% |

| Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.0 | -100.0% | -100.0% |

| Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services | 3.5 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.3 | -14.4% | -17.9% |

| Health Care Fraud & Abuse Control base fundinga | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | -10.6% | -1.9% |

| Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program | 5.1 | 5.7 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.4 | -41.0% | -2.7% |

| Refugee & entrant assistance | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 74.8% | -10.1% |

| Child Care & Development Block Grant | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.3% | -1.9% |

| Head Start | 7.2 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 8.6% | 0.3% |

| Other Administration for Children & Families programs | 2.0 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | -17.1% | -1.2% |

| Administration for Community Living | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 | -9.9% | -0.8% |

| Public Health & Social Services Emergency Fund | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | -22.3% | -2.2% |

| Dept. mgmt. & other | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | -44.7% | -13.3% |

a Does not include program integrity spending eligible for a cap adjustment under the 2011 Budget Control Act.

Note: Figures do not include emergencies. Minor adjustments have been made where necessary to make the categories comparable across years. Where applicable, figures include amounts the bill directs to be transferred to the program through the “Public Health Service evaluation transfer” mechanism and from the Prevention and Public Health Fund; totals do not add as a result. Reflects only funding in the Labor-HHS-Education appropriations bill, not amounts appropriated for HHS in other bills.

Source: CBPP analysis of House Appropriations Committee data

Department of Labor

The bill cuts the Department of Labor by $204 million relative to 2015, bringing the inflation-adjusted reduction since 2010 to $3.4 billion (22 percent).

Job training. The bill cuts overall funding for job training by $135 million below 2015. This area has already been cut substantially over the last five years. In fact, the bill’s overall level for job training is $1.5 billion — more than one-fifth — below 2010 in inflation-adjusted terms. These cuts continue despite last year’s enactment, with overwhelming bipartisan support, of legislation to overhaul and re-authorize federal job training programs and increase authorized funding.

The bill’s main cut in job training comes from reducing the “national reserve” portion of the dislocated workers employment and training program by two-thirds, from $221 million to $74 million. While most dislocated training assistance is distributed to states by formula, the national reserve provides extra help in responding to large disruptions such as plant closings, mass layoffs, and natural disasters, as well as to support demonstration projects and technical assistance.

Worker protection agencies. The bill cuts total funding by $36 million for Labor Department agencies that enforce worker protections such as the minimum wage, health and safety standards, and retirement and other employee benefits. The cumulative cut since 2010 would be $191 million (11 percent) after adjusting for inflation.

For example, the bill includes a $12 million cut for the Wage and Hour Division, which enforces federal laws regarding minimum wages, overtime requirements, family and medical leave, and similar matters. The bill also cuts funding for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) by $18 million, with cuts particularly targeted to federal enforcement and safety and health training for workers. The cumulative reduction for OSHA since 2010 would be 14 percent, adjusted for inflation.

International labor affairs. The bill cuts funding for these programs by about two-thirds, from $91 million to $32 million. The committee report says that the cut is meant to eliminate funding for the Labor Department’s international grant programs, which are primarily for projects to help eliminate child labor, as well as other initiatives to improve labor standards and protections abroad.

| TABLE 4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department of Labor Appropriations Overview (in billions of dollars) | |||||||

| 2010 enacted | 2015 enacted | 2016 | Percent change, adjusted for inflation | ||||

| current dollars | 2016 dollars | current dollars | 2016 dollars | House bill | 2010 to 2016 |

2015 to 2016 |

|

| Department of Labor, total | 13.5 | 15.1 | 11.9 | 12.2 | 11.7 | -22.5% | -3.6% |

| Job training, including Job Corps and veterans’ programs | 5.8 | 6.5 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.0 | -23.4% | -4.5% |

| Unemployment Insurance & Employment Service operations | 4.1 | 4.6 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.6 | -22.2% | -2.4% |

| Senior Community Service Employment Program | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | -53.0% | -1.9% |

| Worker protection agencies | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | -10.9% | -4.2% |

| Bureau of Labor Statistics | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | -11.0% | 0.9% |

| International Labor Affairs | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | * | -69.1% | -65.6% |

| All other | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | -5.6% | 2.9% |

* Less than $50 million

Note: Figures do not include emergencies.

Source: CBPP analysis of House Appropriations Committee data

Other Agencies

Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS). The bill cuts CNCS, which operates a number of domestic service programs (including AmeriCorps, VISTA, and several programs for seniors), by more than one-third. The cuts are primarily to AmeriCorps, which provides funding for public service jobs, frequently in economically disadvantaged areas. These cuts would significantly reduce the number of positions AmeriCorps could fund and threaten the modest educational stipend that AmeriCorps workers receive after completing a year of public service work.

National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). The bill cuts the NLRB by more than one-quarter, from $274 million to $200 million. The NLRB enforces federal laws guaranteeing workers’ rights to improve their working conditions, including by unionizing, and conducts secret-ballot elections to determine if workers wish to be represented by a union. The Administration indicates that this budget cut would require the NLRB to reduce staffing by at least one-third, hampering its ability to investigate and act against unfair labor practices and conduct representation elections.

| TABLE 5 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriations Overview for Related Agencies (in billions of dollars) | |||||||

| 2010 enacted | 2015 enacted | 2016 | Percent change, adjusted for inflation | ||||

| current dollars | 2016 dollars | current dollars | 2016 dollars | House bill | 2010 to 2016 |

2015 to 2016 |

|

| Related agencies, totala | 13.6 | 15.2 | 13.1 | 13.3 | 12.6 | -17.0% | -5.1% |

| Corp. for Nat’l & Community Service | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.7 | -46.5% | -36.1% |

| Corp. for Public Broadcasting | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | -25.1% | -1.9% |

| Social Security Administration a | 11.1 | 12.4 | 10.8 | 11.0 | 10.8 | -12.7% | -1.8% |

| Other related agencies | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | -26.7% | -11.3% |

a Does not include program integrity spending eligible for a cap adjustment under the 2011 Budget Control Act. Note: Figures do not include emergencies.

Source: CBPP analysis of House Appropriations Committee data

Más sobre este tema

House Bill Would Raise Medicare, Medicaid Costs and Deficits, Stifle Health Care Innovation

Compendios de política pública

Presupuesto federal

End Notes

[1] Of that reduction, $5 billion reflect rescissions, various changes in mandatory programs (“CHIMPs”), and other “scorekeeping adjustments.” Leaving those items aside, the programmatic cuts since 2010 total $24 billion (13 percent) after adjusting for inflation.

[2] David Reich, “House Bill Would Circumvent Budget Cap for Defense,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 14, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/house-bill-would-circumvent-budget-cap-for-defense.

[3] Michael Leachman and Chris Mai, “Most States Still Funding Schools Less Than Before the Recession,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 16, 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/research/most-states-still-funding-schools-less-than-before-the-recession.

[4] For more on Pell Grants’ funding gap, see Brandon DeBot and David Reich, “House Budget Committee Plan Cuts Pell Grants Deeply, Reducing Access to Higher Education,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 24, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/house-budget-committee-plan-cuts-pell-grants-deeply-reducing-access-to-higher-education.

[5] For more information, see Edwin Park, “House Bill Would Raise Medicare, Medicaid Costs and Deficits, Stifle Health Care Innovation,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 23, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/house-bill-would-raise-medicare-medicaid-costs-and-deficits-stifle-health-care-innovation.

[6] For more information, see Kathleen Romig, “Underfunding Weakens Social Security’s Service to the Public,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 24, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/underfunding-weakens-social-securitys-service-to-the-public.

[7] If adjusted instead for inflation in biomedical research costs — rather than general inflation — the bill’s level is 10.4 percent below 2010.

[8] Figures given for total CDC funding include amounts transferred from the Prevention and Public Health Fund, a mandatory fund established by the ACA. The bill allocates amounts in the Fund to various specific uses at CDC and other agencies.

Más de los autores