Cassidy-Graham Deepens Medicaid Per Capita Cuts for Certain High-Cost States

Like other Republican bills repealing the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the bill sponsored by Senators Bill Cassidy and Lindsey Graham, which the Senate may consider this week, would radically restructure Medicaid by converting virtually the entire program to a per capita cap and deeply cut federal Medicaid spending over time. Cassidy-Graham incorporates a little-noticed provision from the failed Senate Republican leadership bill — the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) — that would disproportionately cut federal Medicaid funding for certain states with higher-than-average per-beneficiary costs.[1] Compared to the BCRA, Cassidy-Graham actually penalizes high-cost states more severely. Compared to the BCRA, Cassidy-Graham actually penalizes high-cost states more severely, because the additional cuts would apply permanently, rather than just for one year. The provision could hit states like Kansas, Indiana, New York, Massachusetts, and Minnesota particularly hard.

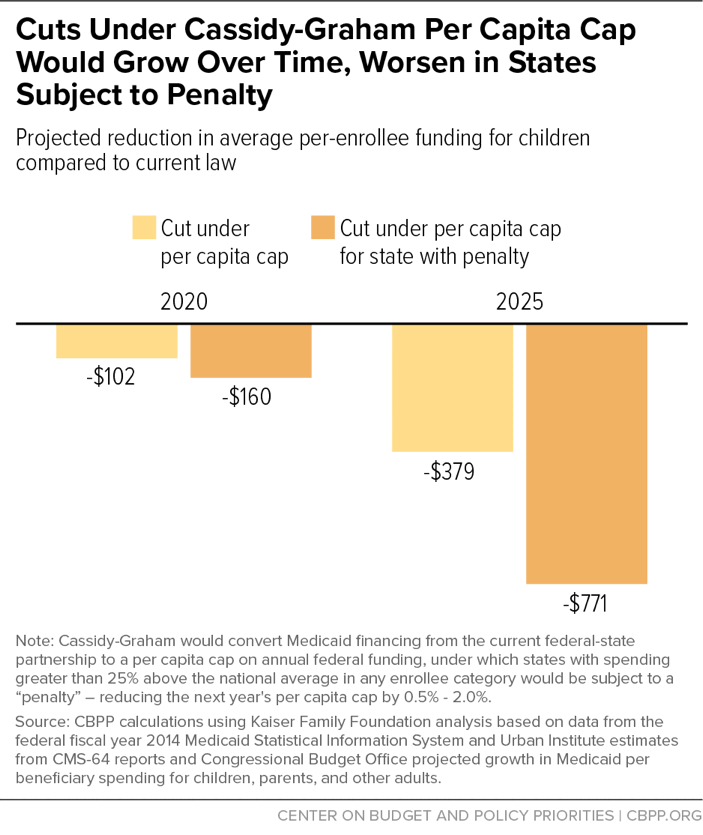

Starting in 2020, Cassidy-Graham would establish separate per-beneficiary caps for different groups: children, seniors, people with disabilities, and other adults (largely parents). Each year, states would receive a fixed amount of overall federal funding based on these caps and enrollment in each beneficiary group. States’ caps would grow more slowly over time than currently projected increases in Medicaid spending per beneficiary. Earlier estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) suggest that Cassidy-Graham would cut the rest of Medicaid (outside the ACA’s Medicaid expansion) by $175 billion between 2020 and 2026, with the cuts reaching $39 billion by 2026 or 8 percent relative to current law.[2] These cuts would grow even deeper in coming decades, lowering federal Medicaid spending by $1.1 trillion through 2036 (outside the expansion), according to new estimates from Avalere.[3]

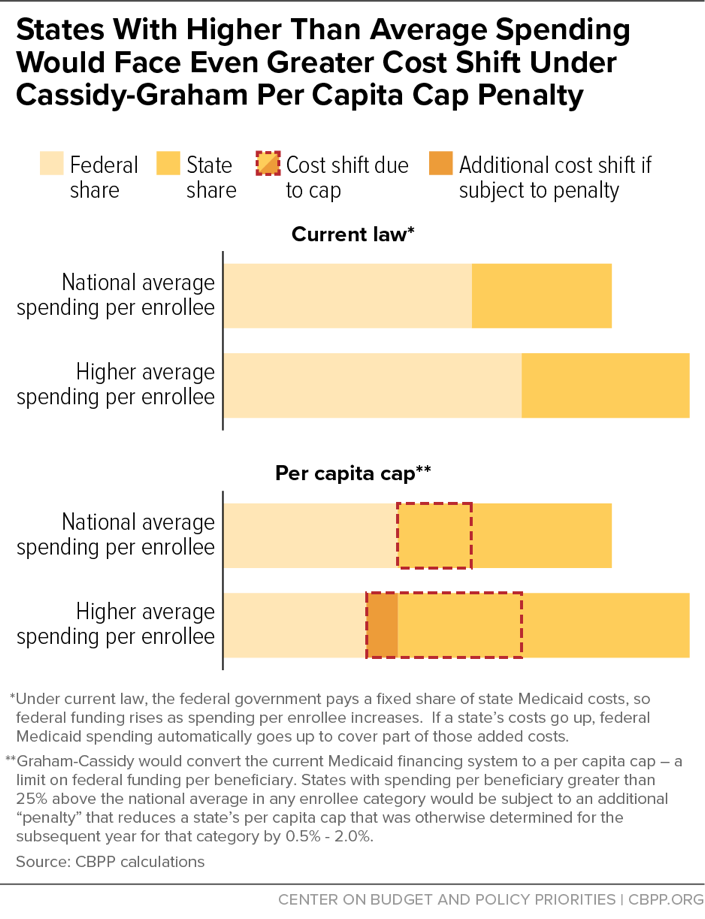

While the per capita cap in Cassidy-Graham would shift substantial Medicaid costs to all states, some states would likely face disproportionately large cuts, due in part to a provision that effectively imposes a penalty on states with high per-beneficiary Medicaid costs in one of the beneficiary groups. If a state’s total federal and state per-beneficiary spending is more than 25 percent higher than the national average for any group, the state’s per capita cap amount for that group for the following year would be reduced between 0.5 percent and 2 percent. (The Secretary of Health and Human Services would have the discretion to determine the specific adjustment within that range.) At the same time, states with lower-than-average per-beneficiary spending for an eligibility group would see an increase in their per capita cap amount for the following year.

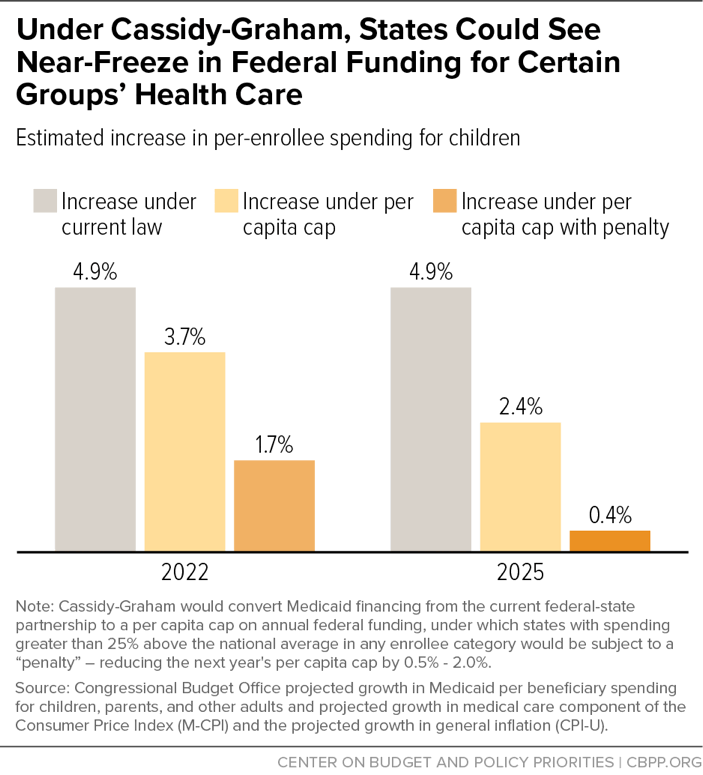

What would this mean in practice? Take states’ per capita cap amount for children, which starting in 2025 would only be annually increased by the general inflation rate (CPI-U). The CBO assumes that CPI-U would grow 2.4 percent annually, but that is about 2.5 percentage points lower than what it projects for increases in per-beneficiary costs for those groups nationwide. A state affected by this penalty provision thus could see its annual adjustment effectively cut to 0.4 percent, effectively freezing that state’s per capita cap amount for the following year.

Unlike the BCRA, these adjustments would also permanently be built into the state’s per capita cap for that eligibility group, meaning that these disproportionately larger cuts would remain permanently in effect. If a state has a temporary spike in spending due to a breakthrough medical treatment or a crisis like the opioid epidemic, which results in higher spending per beneficiary for a group in excess of the 25 percent threshold, that could cause the state’s per capita cap to be permanently reduced. And if a state has high costs for several years, the cuts would compound.

The per capita cap and adjustment also fail to recognize the many reasons state spending varies. States have very little control over many of the factors that affect their spending on Medicaid beneficiaries. While states can control some factors, such as the optional benefits they offer and the rates they pay providers, they can’t significantly affect many factors related to per-beneficiary Medicaid spending, such as the relative health or demographics of their Medicaid population or the rising cost of prescription drugs. For example, states with large numbers of baby boomers who will need costly care as they age could be hit hard by these penalties, including New York, Arizona, and New Mexico, driving up the average age and costs of their seniors on Medicaid.[4]

These states could see their federal funding decrease even further at exactly the time when their state costs are increasing to help care for these vulnerable groups. The bill would exempt from this penalty only those five states with very low population density: Alaska, Wyoming, Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota, according to 2010 Census data.

Moreover, these adjustments would be calculated annually based on average national spending — in other words, states would be graded on a curve. If a high-spending state makes deep cuts to avoid the penalties in the same year that other states also make cuts, it could cause states to make deeper and deeper cuts to their programs to avoid incurring the penalty in the following year.

If this penalty had been implemented in 2014, the following 24 states and the District of Columbia would have seen additional per capita cap reductions in at least one beneficiary group: Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and West Virginia.

Deepening Medicaid cuts for states with high costs wouldn’t make Medicaid funding more equitable or increase access to needed care. To the contrary, it would pit states against each other, creating a race to the bottom where states make deeper and deeper cuts to their programs to avoid the penalty — a race that Medicaid beneficiaries would be likely to lose. And for some states like Kansas, Indiana, and New York, which would already face disproportionate federal funding cuts under the Cassidy-Graham block grant, this provision would make the harmful per capita cap — which would drive $1.1 trillion in Medicaid cuts through 2036 — even more damaging.

Más sobre este tema

CBO: Cassidy-Graham Would Increase Uninsured by Millions, Cut Medicaid by $1 Trillion

Cassidy-Graham Would End Medicaid Expansion in 2020, Leave Millions of Low-Income Adults Uninsured

End Notes

[1] Hannah Katch, “Senate Health Bill Deepens Medicaid Cuts for High-Cost States,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 23, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/senate-health-bill-deepens-medicaid-cuts-for-high-cost-states.

[2] CBPP calculations based on Congressional Budget Office estimates of July 20 version of Senate Republican leadership bill (Better Care Reconciliation Act), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/52941-hr1628bcra.pdf.

[3] Elizabeth Carpenter and Chris Sloan, “Graham-Cassidy-Heller-Johnson Bill Would Reduce Federal Funding to States by $215 Billion,” Avalere, September 20, 2017, http://a valere.com/expertise/life-sciences/insights/graham-cassidy-heller-johnson-bill-would-reduce-federal-funding-to-sta.

[4] Matt Broaddus, “Population’s Aging Would Deepen House Health Bill’s Medicaid Cuts for States,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 24, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/populations-aging-would-deepen-house-health-bills-medicaid-cuts-for-states.

Más de los autores