más allá de los números

Rush to Pass Senate Health Bill Would Be Designed to Hide Its Impact

The effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has followed a recurring pattern: congressional Republican leaders introduce a bill that Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis subsequently shows to be extremely damaging. GOP leaders then make some changes to the bill that they claim have fixed the problems, but further CBO analysis reveals that isn’t the case. We’re likely to see more of the same this week. This time, however, there’s a risk that the damaging bill could be signed into law before CBO issues an analysis showing its true impact.

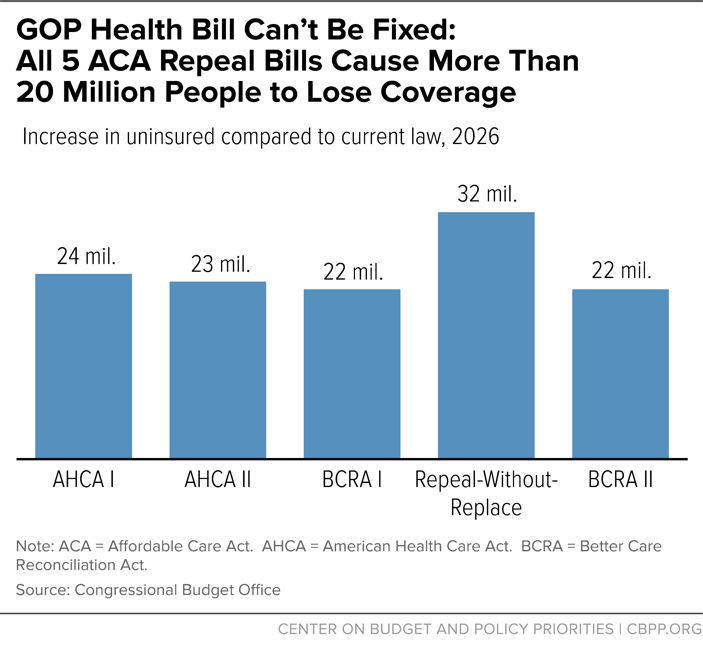

Here’s how the process has unfolded several times in recent months: First, Republicans offer a version of their legislation that includes the same structural features: deep cuts to Medicaid, less financial assistance to people purchasing health insurance on the individual market, measures that undermine the ACA’s guarantee that people with pre-existing conditions can buy affordable coverage that meets their needs, and tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations. Next, CBO finds that the legislation would result in at least 20 million people losing coverage, millions more facing higher costs, and people with pre-existing conditions being placed at risk. Finally, congressional Republican leaders promise that the next version of the bill will solve these problems — only to repeat the process over again.

In most of these cases, the CBO scores — showing large coverage losses and significant out-of-pocket cost increases (see chart), effectively debunking Republican talking points — have temporarily stalled the legislation. But in May, the House leadership passed its health bill after unveiling changes that it claimed fixed the bill — but before CBO had time to analyze the revised measure. Once CBO did, it concluded that those fixes made little difference to the harm the bill would do, as described below. It appears that Senate leaders may be planning to use the same approach — pass a series of amendments and then immediately proceed to a vote on final passage without a CBO analysis of the legislation’s impact, which likely would show that the newest version again fails to do what has been promised.

We can see how that might unfold this week. On Tuesday, the Senate could move to a procedural vote to begin floor consideration of a bill — even though, as Senate Majority Whip John Cornyn has said, knowing what version of the legislation they’re pursuing is a “luxury we don’t have.” A vote on final passage of a bill could then come as soon as Thursday, with the final legislative text made available only shortly before the vote — and without a full CBO analysis of the impact on coverage and on premiums and deductibles. Once again, congressional leaders may promise that the bill has been “fixed” — with the information needed to assess that claim not available until after the vote (see table).

-

It may not be clear what bill the Senate plans to vote on until the very end of the process. The Senate appears likely to consider at least two different pieces of legislation if a Motion to Proceed vote passes on Tuesday, enabling the Senate to take up the legislation: a version of the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA, the Senate’s replacement for the ACA that on Tuesday CBO scored as adding 22 million people to the ranks of the uninsured) or the Obamacare Repeal Reconciliation Act (ORRA, a bill that repeals most of the ACA without a replacement, scored by CBO as adding 32 million to the ranks of the uninsured.) Additionally, Senators Lindsay Graham and Bill Cassidy appear to be shopping their own “amendment” that deeply cuts Medicaid and subsidies that help moderate-income people afford coverage, but structures these cuts differently than either the BCRA or the ORRA — though they’ve provided no details beyond a short press release about what that legislation would entail.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell could not only bring up any of these three distinct pieces of legislation as amendments while on the floor, but — at the end of the amendment process and right before the vote on final passage — he could introduce a significantly modified version of any of these bills (or even a different bill). That new bill could be introduced just hours before a final vote, with virtually no opportunity for the Senate, let alone the public, to assess it. (This could be true even if the Senate takes steps to extend the time between a successful Motion to Proceed vote and a vote on final passage.) The result could be a “bait-and-switch”: debate over one set of proposals, followed by a vote on a different piece of legislation.

| Senate Could Vote on Little-Understood Health Care Legislation This Week | |

|---|---|

| While the exact timing on the floor remains unknown, here’s one way the debate could unfold: | |

| Tuesday | Vote on Motion to Proceed, likely without clarity on what version of legislation Senate leadership seeks to pass at the end of the process |

| Tuesday-Thursday | 20 hours of debate, including consideration of amendments. The Senate could vote on amendments that may include:

|

| Thursday | McConnell could introduce a final substitute, which will need CBO confirmation that it meets fiscal targets but won’t need a more comprehensive CBO estimate that includes impacts on coverage, Medicaid spending and enrollment, individual market premiums and out-of-pocket costs, people with pre-existing conditions, and the stability of the individual market |

| Thursday | Vote on final passage |

-

The Senate thus may vote on final passage without a CBO score showing the bill’s coverage impact. Sen. McConnell could force a vote on this new substitute proposal without a CBO analysis of its impact on health coverage and the cost of health insurance, and with only a limited fiscal analysis. That would enable senators who vote for the final bill to assert that the bill has been “fixed” and covers more people, reduces Medicaid enrollment losses, or increases premiums and out-of-pocket costs much less than CBO’s earlier analyses indicated, without credible evidence.

Indeed, undecided senators have expressed concern over issues like the time provided to phase out the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, the depth of the Medicaid cuts, the affordability of insurance for low-income consumers, and the impact of the Cruz amendment on pre-existing conditions. Some senators could portray various modifications in these areas as major victories that have secured their votes — even if the changes have little overall impact on coverage and consumer costs. (Some of these “victories” might simply amount to returning to language in the House bill that these senators once viewed as unacceptable.) Without a comprehensive CBO score of the final bill before senators vote, there will be no official data with which to assess the impact of the changes to the bill.

-

This is an extreme version of a dynamic we’ve seen before, with the Upton amendment in the House. Introduced near the end of House consideration of its ACA repeal bill, the Upton amendment sought to allay criticism that people with pre-existing conditions couldn’t find affordable coverage if states waived “community-rating” requirements under the MacArthur amendment, by providing $8 billion for high-risk pools. (In many ways, the concerns that the Upton amendment were meant to address are similar to those raised with regard to the Cruz amendment.) While prior history and independent analysis both questioned whether the Upton amendment’s funding would be anywhere near sufficient, House leaders claimed — without waiting for a CBO analysis — that the money would “allow people with pre-existing conditions who haven’t maintained continuous coverage to acquire affordable care.”

CBO later confirmed that the funding “would not be sufficient to substantially reduce the large increases in premiums for high-cost enrollees.” But CBO didn’t release that analysis until weeks after the House passed the bill, with members having justified their “yes” votes based on the very claims that CBO later refuted.

The Senate process could involve a more extreme version of this approach, where the so-called “fix” isn’t simply one addition, but a revamped bill.

-

The Senate could introduce and pass legislation within hours that could become law only days later. Unlike the House-passed bill — which was destined to undergo further changes in the Senate and return to the House — the Senate may never have an opportunity to vote on the bill again, after CBO completes its analysis. House leaders reportedly may rush a vote immediately after Senate passage. This means that the bill could pass the House as well — sending it to the President for his signature — before policymakers and the public understand the implications of the Senate’s last-minute changes.

Of course, CBO will eventually release its analysis of the final bill. That analysis would very likely contradict the promises senators have made in the run-up to the vote. But those contradictions would become clear only after the bill and its highly damaging provisions are already the law of the land.