The Realities of Work for Individuals with Disabilities: Impact of Age, Education, and Work Experience

Remarks at the National Disability Forum

End Notes

[1] Another 3.5 million people aged 18-64 collect Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits because of disability. Although my remarks focus on DI, the medical and vocational rules are essentially the same in DI and SSI.

[2] Social Security Administration, Advance Notice Of Proposed Rulemaking, “Vocational Factors of Age, Education, and Work Experience in the Adult Disability Determination Process,” Federal Register, September 14, 2015, https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/09/14/2015-22839/vocational-factors-of-age-education-and-work-experience-in-the-adult-disability-determination.

[3] Social Security Act, section 223 (Disability Insurance); similar language appears in section 1614 (Supplemental Security Income). By regulation, “substantial gainful activity” (SGA) is currently defined as $1,090 a month — equivalent to less than full-time work at the minimum wage, or about 40 percent of median earnings of a full-time, year-round worker with a high-school diploma but no college.

[4] Appendix 1 to Subpart P of Part 404, Code of Federal Regulations.

[5] Appendix 2 to Subpart P of Part 404, Code of Federal Regulations. The agency offers a plain-English explanation of the entire determination process to applicants at https://www.ssa.gov/planners/disability/dqualify5.html.

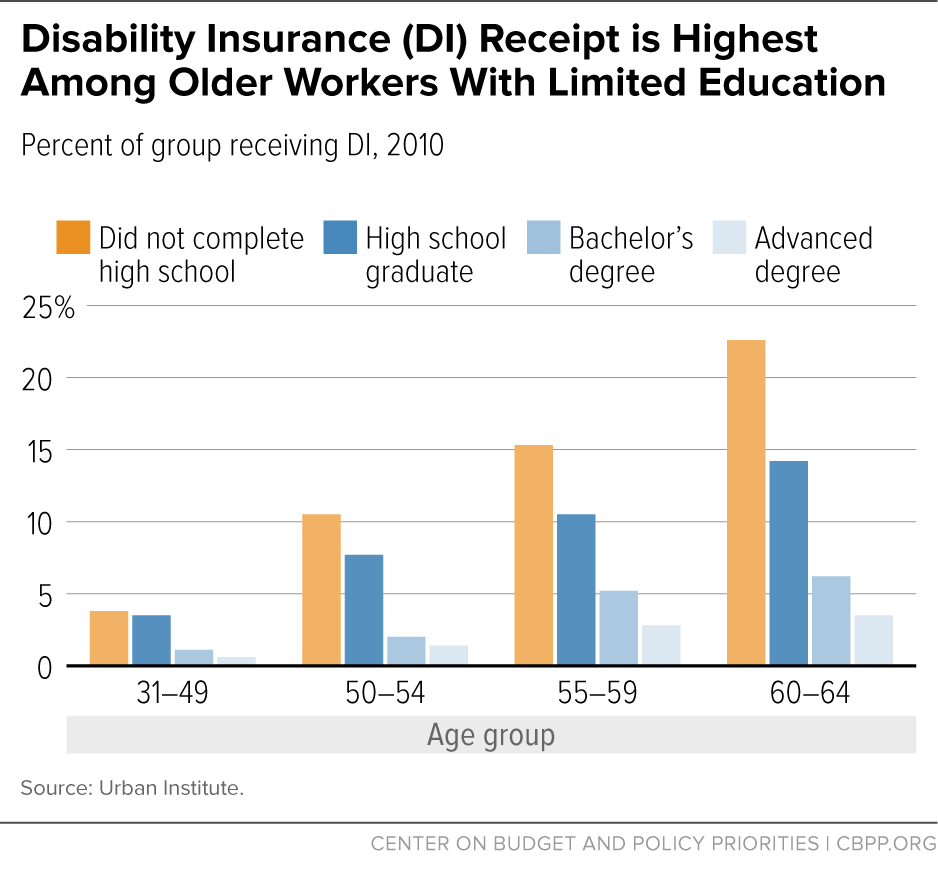

[6] U.S. Census Bureau, Americans with Disabilities: 2010, Current Population Reports, July 2012, http://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/p70-131.pdf.

[7] See Joyce Manchester and Jae Song, “What Can We Learn from Analyzing Historical Data on Social Security Entitlements?,” Social Security Bulletin, Vol. 71 No. 4, 2011, http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v71n4/v71n4p1.html.

[8] Paul O’Leary, Elisa Walker, and Emily Roessel, “Social Security Disability Insurance at Age 60: Does It Still Reflect Congress’ Original Intent?” Social Security Administration, Issue Paper 2015-01 (September 2015), chart 3, https://www.socialsecurity.gov/policy/docs/issuepapers/ip2015-01.html. The paper presents data from two different sources that show different educational attainment rates for SSDI beneficiaries. A range is listed here, as it is unclear which source is more accurate.

[9] Kathy A. Ruffing, “Geographic Pattern of Disability Receipt Largely Reflects Economic and Demographic Factors,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/geographic-pattern-of-disability-receipt-largely-reflects-economic-and-demographic-factors.

[10] Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Sickness, Disability, and Work: Breaking the Barriers — A Synthesis of Findings Across OECD Countries, 2010, http://ec.europa.eu/health/mental_health/eu_compass/reports_studies/disability_synthesis_2010_en.pdf.

[11] Paul N. Van de Water, “4 Reasons Why the Netherlands Isn’t a Model for Disability Insurance,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 17, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/4-reasons-why-the-netherlands-isnt-a-model-for-disability-insurance.

[12] Enrica Croda, Jonathan Skinner, and Laura Yasaitis, “An International Comparison of the Efficiency of Government Disability Programs,” National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Disability Research Center Paper No. NB 13-08, September 2013, http://www.nber.org/aging/drc/papers/odrc13-08.

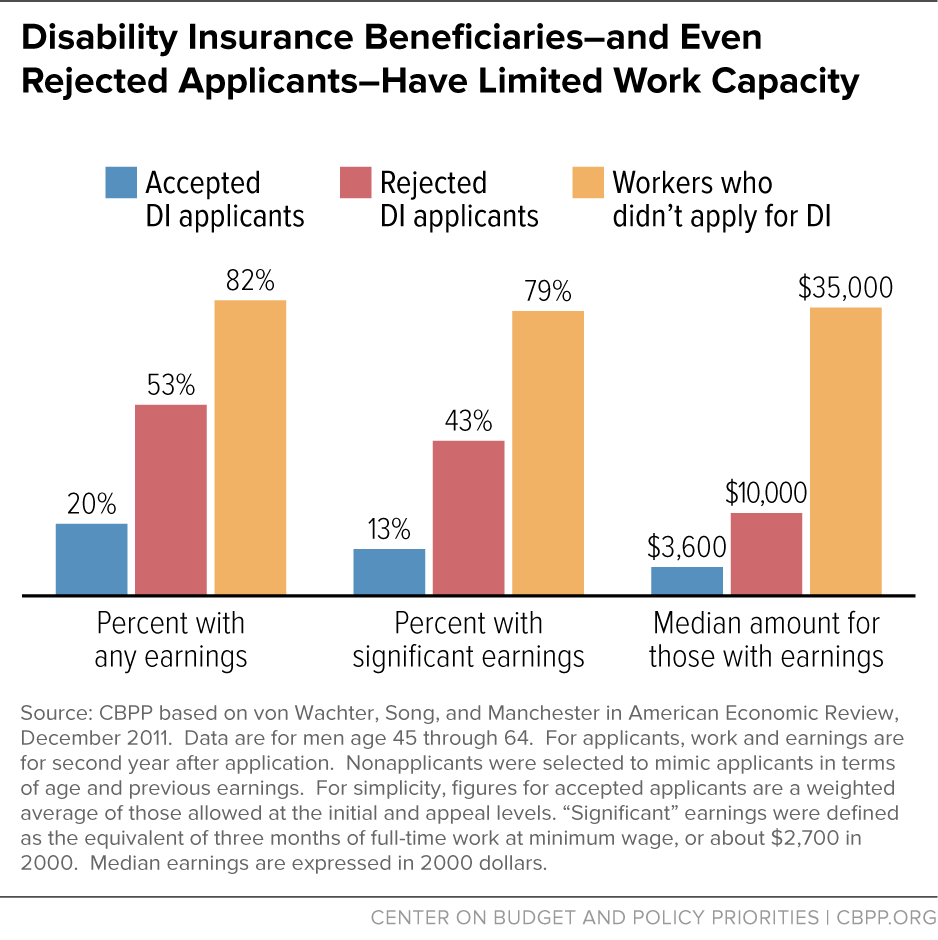

[13] Over the 20090-2011 period — which we use because few applications from those years are still awaiting decision — SSA granted benefits to about 37 percent of all disabled-worker applicants (the award rate). Expressed as a percentage of medical decisions, which excludes people who weren’t insured or who failed other technical criteria, SSA granted benefits in 56 percent of cases (the allowance rate). See Table 60, “Outcomes at all adjudicative levels, by year of application, 1992–2012,” Annual Statistical Report on the Social Security Disability Insurance Program, 2013, Social Security Administration, December 2014, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/di_asr/2013/sect04.html.

[14] Stephen C. Goss, Anthony W. Cheng, Michael L. Miller, and Sven H. Sinclair, “Disabled Worker Allowance Rates: Variation Under Changing Economic Conditions,” Social Security Administration, Actuarial Note 153, August 2013, https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/NOTES/pdf_notes/note153.pdf; Kathy A. Ruffing, “Disability Benefits Are Hard to Get — Even in Recessions,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 3, 2013, http://www.offthechartsblog.org/disability-benefits-are-hard-to-get-even-in-recessions/. (An updated version of the graph may be found in CBPP’s chart book at https://www.cbpp.org/research/chart-book-social-security-disability-insurance.)

[15] Paul N. Van de Water, “Few Disability Insurance Beneficiaries Could Support Themselves by Working,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 9, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/few-disability-insurance-beneficiaries-could-support-themselves-by-working.

[16] Alexander Strand and Brad Trenkamp, “When Impairments Cause a Change in Occupation,” Social Security Bulletin, Vol. 75 No. 4, 2015, https://www.socialsecurity.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v75n4/v75n4p1.html. The sample consisted of applicants aged 27–55 in 2005 (the year of denial) who didn’t appeal to an administrative law judge, and who didn’t have a previous or subsequent DI application. Arguably, these sample restrictions ended up focusing on the most “able” of applicants denied at this final step. The study followed them for six years, through 2011.

[17] Social Security Administration, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, “Age as a Factor in Evaluating Disability,” Federal Register, November 4, 2005, https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2005/11/04/05-21975/age-as-a-factor-in-evaluating-disability. The proposed rule was eventually withdrawn; see https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2009/05/08/E9-10733/age-as-a-factor-in-evaluating-disability.

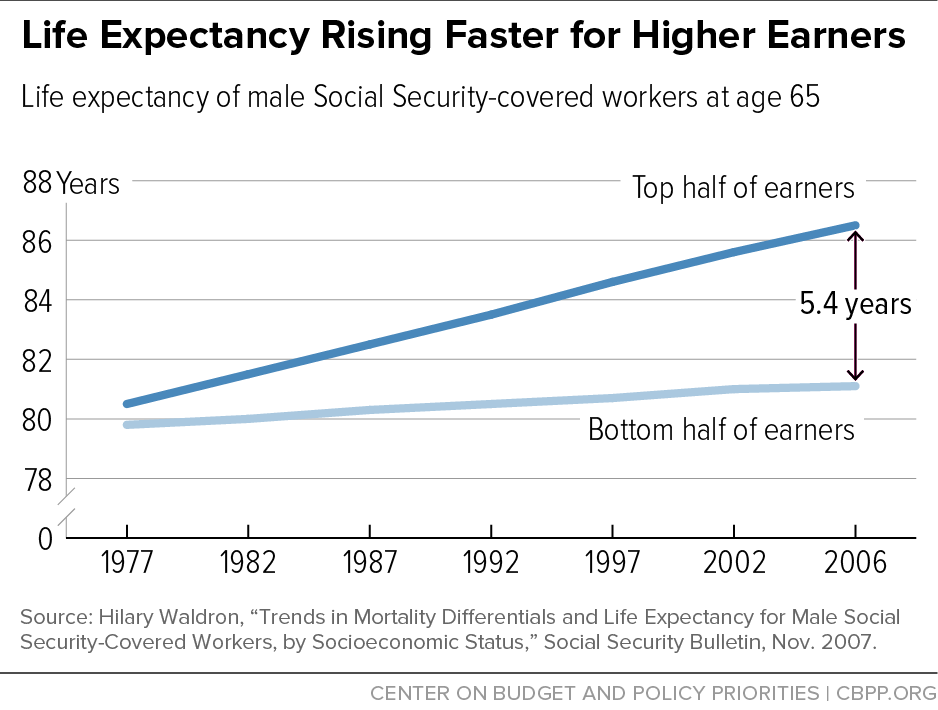

[18] Hilary Waldron, “Trends in Mortality Differentials and Life Expectancy for Male Social Security-Covered Workers, by Average Relative Earnings,” Social Security Administration, ORES Working Paper No. 108, October 2007, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/workingpapers/wp108.html. In that and numerous subsequent papers (listed at https://www.ssa.gov/policy/authors/WaldronHilary.html), Waldron focused on male workers by earnings, using SSA wage data. A 2011 report by the National Academy of Sciences compared mortality trends in the United States and other advanced countries, including the role of inequality — educational, racial, and geographic; Chapter 9, “The Role of Inequality,” in Explaining Divergent Levels of Longevity in High-Income Countries, National Academy of Sciences, 2011, http://www.nap.edu/catalog/13089/explaining-divergent-levels-of-longevity-in-high-income-countries. A recent report focused on widening disparities in longevity by income; The Growing Gap in Life Expectancy by Income: Implications for Federal Programs and Policy Responses, National Academy of Sciences, 2015, http://www.nap.edu/catalog/19015/the-growing-gap-in-life-expectancy-by-income-implications-for.

[19] Arloc Sherman and Eileen Sweeney, “Social Security Administration Proposal to Revise Disability Determinations Is Not Justified,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 18, 2006, https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security-administration-proposal-to-revise-disability-determinations-is-not.

[20] Florian Heiss, Steven Venti, and David Wise, “The Persistence and Heterogeneity of Health Among Older Americans,” NBER Working Paper No. 20306, July 2014, http://www.nber.org/aginghealth/2015no1/w20306.html.

[21] Anna Zajacova, Jennifer K. Montez, and Pamela Herd, “Socioeconomic disparities in health among older adults and the implications for the retirement age debate: a brief report,” Journals of Gerontology, Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 2014, http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/content/69/6/973.full.pdf+html.

[22] Saad Nagi, Disability and Rehabilitation: Legal, Clinical, and Self-Concepts and Measurement, Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1969.

[23] Richard W. Johnson, Gordon B. Mermin, and Matthew Resseger, “Employment at Older Ages and the Changing Nature of Work,” Urban Institute, 2008, http://www.urban.org/research/publication/employment-older-ages-and-changing-nature-work.

[24] Van Doorn Ooms, “A View from Business,” in Virginia P. Reno, Jerry L. Mashaw, and Bill Gradison, Disability: Challenges for Social Insurance, Health Care Financing, and Labor Market Policy, Washington: National Academy of Social Insurance, 1997.

[25] Matthew S. Rutledge, Steven A. Sass, and, and Jorge D. Ramos-Mercado, “How Does Occupational Access for Older Workers Differ by Education?,” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, Working Paper 2015-20, 2015, http://crr.bc.edu/working-papers/how-does-occupational-access-for-older-workers-differ-by-education/.

[26] David R. Mann, David C. Stapleton, and Jeanette de Richemond, “Vocational Factors in the Social Security Disability Determination Process: A Literature Review,” Mathematic Policy Research, DRC Working Paper 2014-07, 2014, http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/our-publications-and-findings/publications/vocational-factors-in-the-social-security-disability-determination-process-a-literature-review.