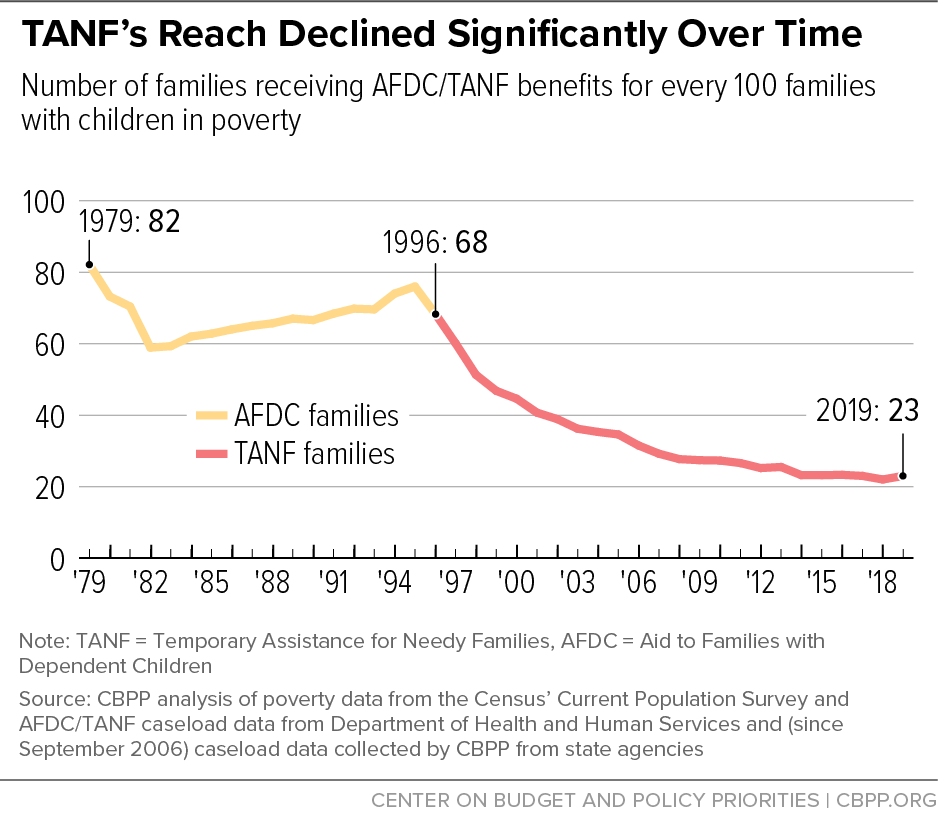

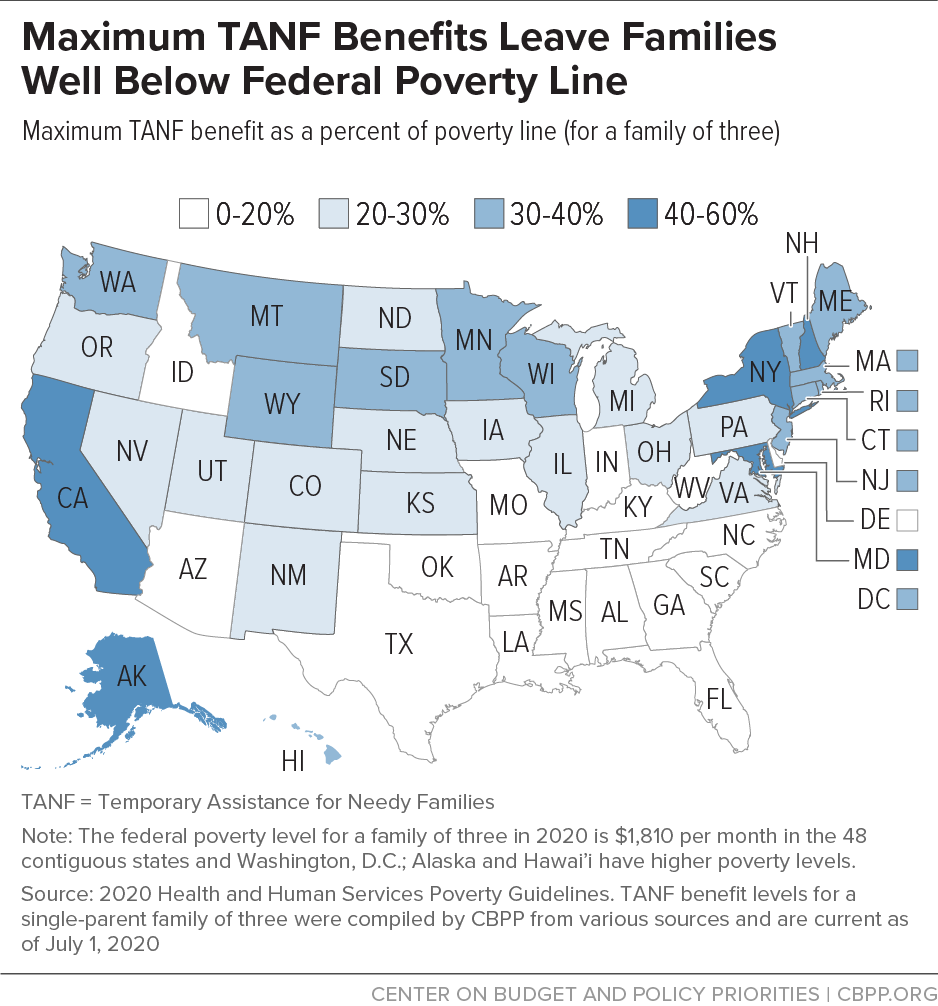

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant provides cash assistance to help families meet their basic needs, but it is not the success that Republican lawmakers claim.[1] Just 23 of every 100 families with incomes below the federal poverty line receive TANF benefits, down from 68 families upon the program’s creation 25 years ago. Benefits are insufficient to lift a family out of poverty in any state, and in 18 states they are at or below just 20 percent of the poverty line.

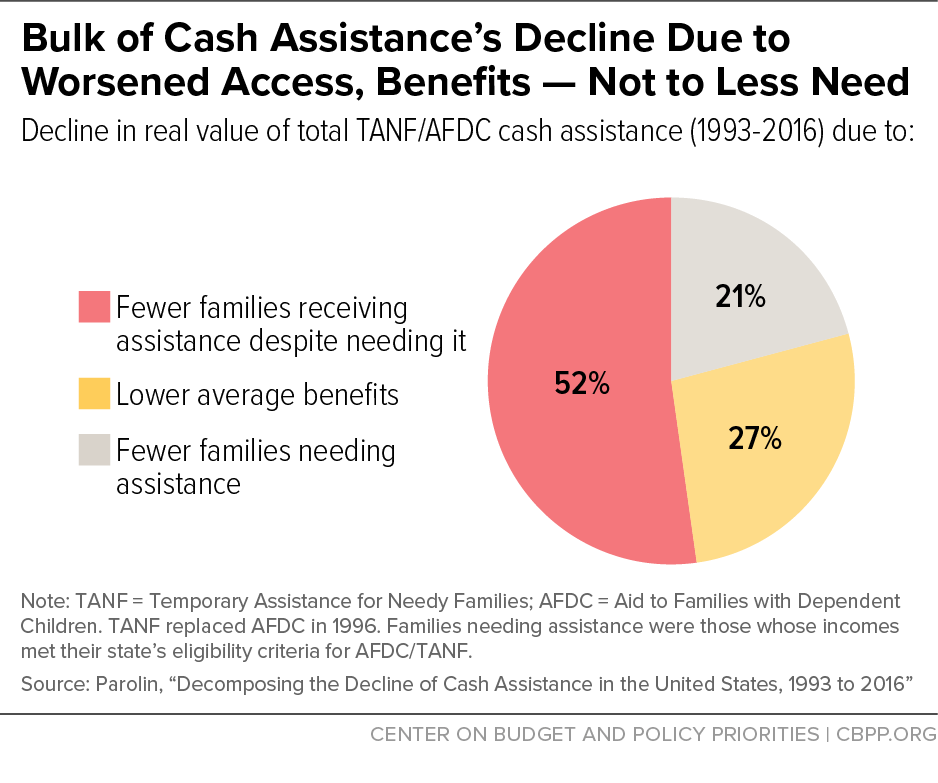

Recent research shows that claims of TANF’s success are vastly overstated. The real (inflation-adjusted) value of the total amount of TANF cash assistance provided annually to families under TANF and its predecessor fell 78 percent between 1993 and 2016, according to a recent study.[2] Over half of that decline was due to fewer families participating in the program despite needing it, and over a quarter was due to lower average benefit levels. Just one-fifth of the decrease was due to reduced need, which includes any increase in employment that might have occurred. (See Figure 1.)

Claims of TANF’s success rest on support for TANF’s supposed work “incentives” — it has stringent time limits and rules that take away benefits for failing to meet work requirements — but researchers find that TANF has failed to substantially improve recipients’ income and financial well-being, even when they find increases in employment.[3] Recipients who leave TANF for work end up in jobs characterized by periods of joblessness and below-poverty incomes. Many recipients with the most limited job prospects never find employment. And the law gives states unfettered flexibility to determine benefit levels and policies on eligibility and work, which has resulted in inequitable outcomes: Black children are more likely than white children to live in states with the weakest TANF programs.

In short, TANF promised “work, not welfare”[4] but left many families with neither. Here are four ways in which TANF is not the success that some claim:

- Its work requirements caused a rise in deep poverty.

- Its work requirements haven’t helped recipients find quality jobs.

- It reaches few families in need.

- Its benefit levels are too low and continue to lose value.

People touting TANF’s supposed success often point to studies of mandatory work programs conducted before TANF’s creation in 1996 or during its early years, often ignoring the studies’ full findings and changes that have occurred since then.[5] Employment increases among program participants were modest at best and faded over time: at least three-quarters of recipients worked by the fifth year of leaving the program regardless of whether they faced work requirements.

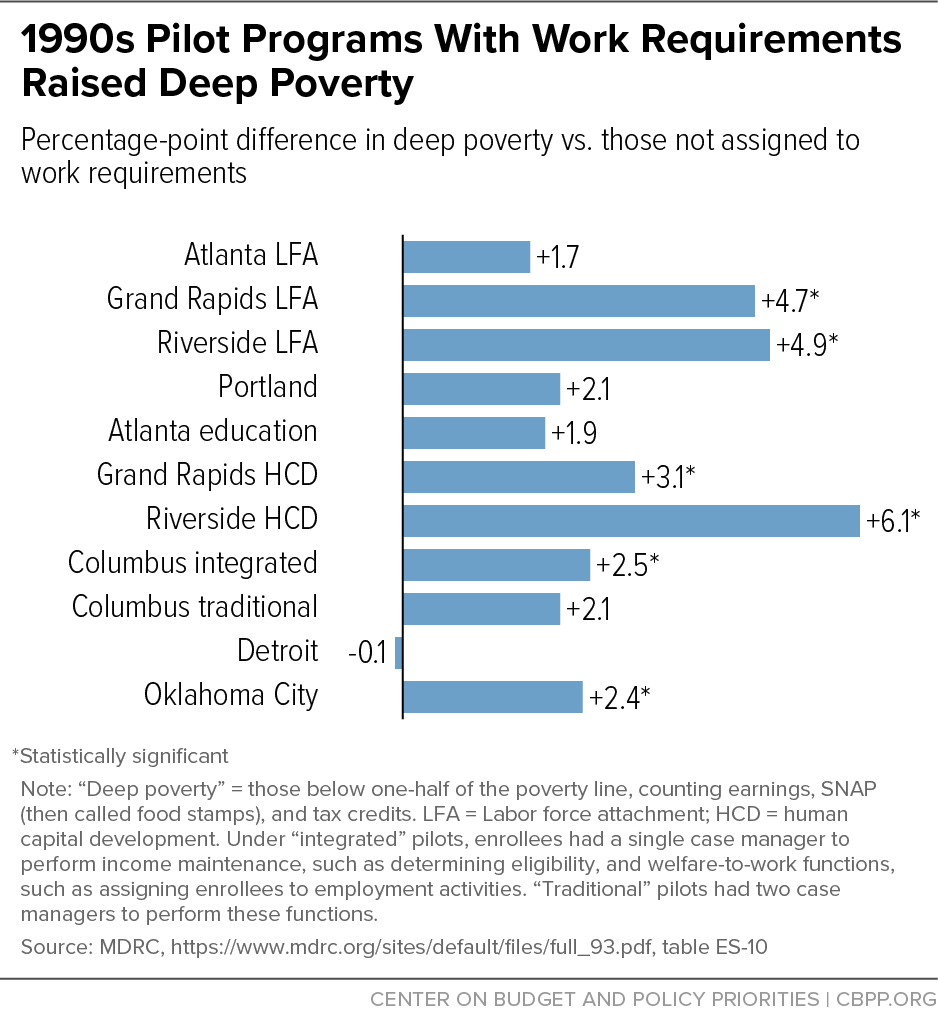

The modest increases in employment resulting from TANF’s emphasis on work came at a significant cost to some families, especially those with significant barriers to employment. The same studies that find increases in employment find that work requirements caused a rise in deep poverty (income below half the poverty line) for recipient families.[6] One study that examined 11 pilot programs — local forerunners of TANF’s work requirements — found that while most of them slightly improved short-term employment, deep poverty rates rose by a statistically significant amount in six of the 11 programs and didn’t fall significantly in any. (See Figure 2.)

From 1995 to 2005 — essentially the decade after the 1996 law created the restrictive TANF program and repealed its predecessor —deep poverty rose from 5.4 percent to 7.4 percent among children in single-mother families, whom the law most affected.[7] Due to this increase, 300,000 more children lived in deep poverty in 2005. Meanwhile, the number of families receiving cash assistance fell by 2.7 million, even though the number of single mothers without a job fell by only 400,000.

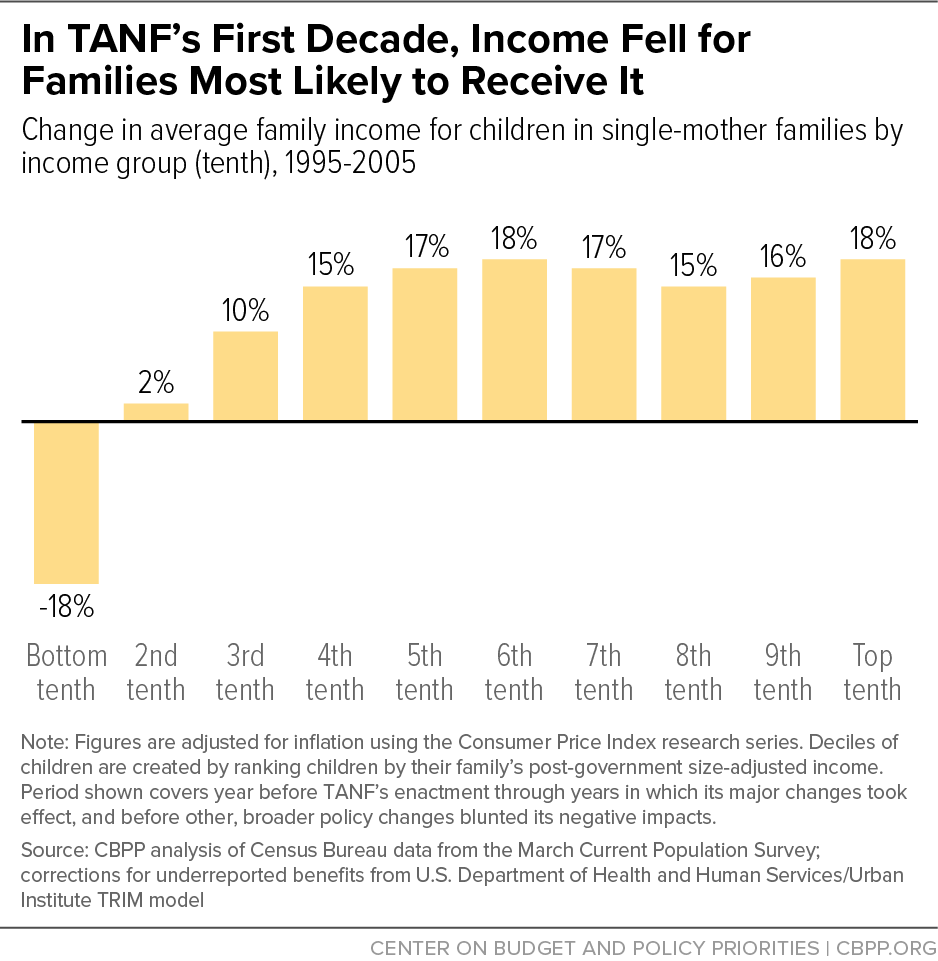

Also over this period, the average family income of the poorest tenth of children in single-mother families, comprising about 2 million children, fell by nearly $2,400, using a comprehensive measure of family income.[8] These losses were driven by a $2,800 fall in TANF cash assistance. Incomes rose for every other income group of children of single mothers. (See Figure 3.) More recently, stronger programs helped to reduce deep poverty among children. The deep poverty rate among children fell from 3.5 percent in 2005 to 2.7 percent in 2016. This decline was largely driven by the improved anti-poverty effectiveness of government assistance programs other than TANF.

Most parents who leave TANF work both before and after leaving, in spite of labor market disadvantages, a recent review of the research finds. Employment rates were modestly higher after exit than before exit, most studies show, with at least 6 in 10 and up to 8 in 10 leavers working during the first year after exit.[9] But few worked steadily throughout that year; many TANF recipients are among the millions of workers in the low-wage labor market, where income volatility and job turnover are high.[10]

Studies consistently find lower employment rates among parents whose TANF cases were closed due to a parent not meeting a work requirement or due to a time limit than among those who left TANF for other reasons. In Illinois, for example, parents who lost assistance because they didn’t meet a work requirement were 44 percent less likely to be employed than those who left TANF for other reasons, even after controlling for other employment characteristics such as previous work experience.[11]

Many parents receiving TANF face significant barriers to employment, including low educational attainment or work experience, lack of reliable access to child care or transportation, or domestic violence. Studies have also documented higher rates of physical and behavioral health conditions, especially among parents whose TANF benefits are taken away for failing to meet a work requirement or due to a time limit. Also, recipients’ age and experience levels often limit their job prospects; almost half of adults receiving TANF are under 30.[12]

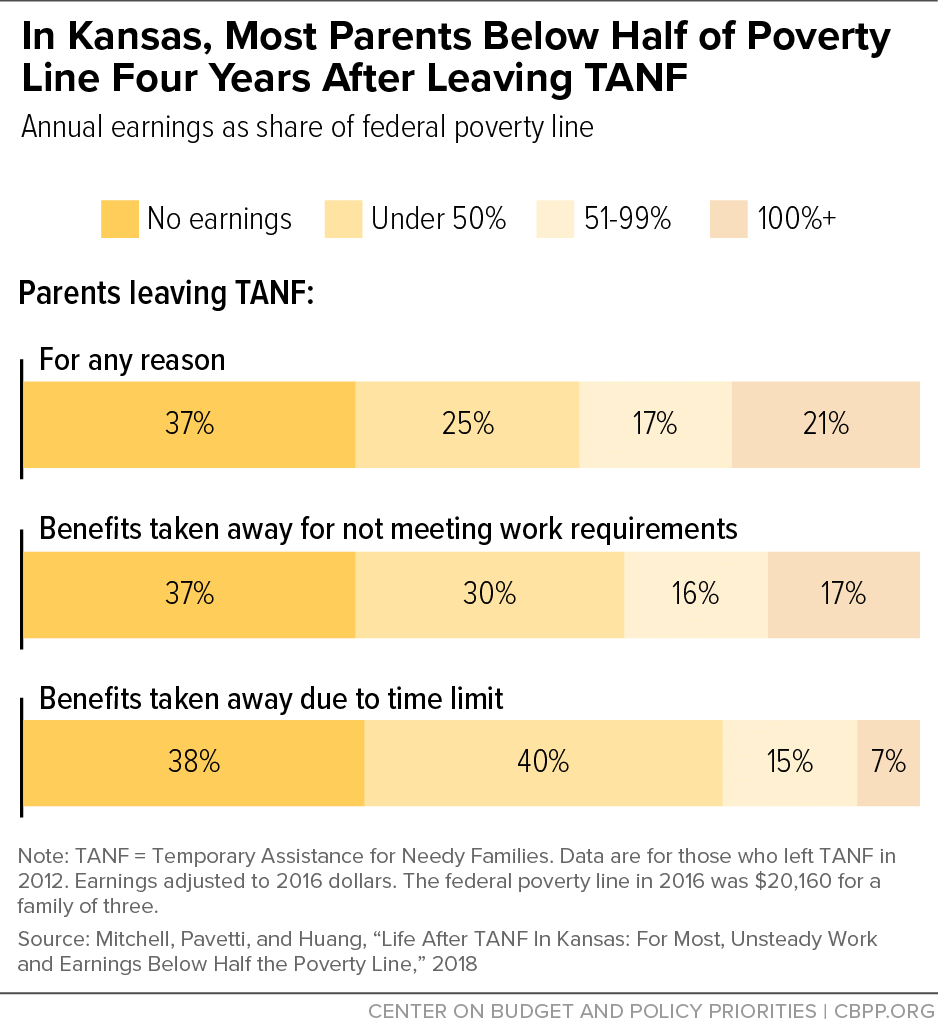

Data from Kansas illustrate how little families earn and how unstable employment is when they leave TANF for work. In any given quarter of the post-exit year, only 55 percent of parents who left TANF were working. Low earnings and poverty persisted even four years after parents left TANF; over a third had no earnings and only one-fifth had income above the poverty line. (See Figure 4.) Outcomes were even worse for families whose TANF benefits were taken away due to a work requirement or time limit.

TANF recipients face a labor market rife with disparities that limit their ability to find work and get paid enough to lift their families out of poverty. Black and Latina women, who make up a majority of adult TANF recipients,[13] experience the dual burden of racial and gender disparities in the labor market. They are paid less than white women (and men) for similar work but are more likely to be their family’s primary breadwinner and face longer stints of joblessness.[14]

The most consequential change in TANF over the last 25 years is the decline in the number of families receiving cash assistance, even as poverty and deep poverty remain widespread. In 2019, 4.5 million families with children were in poverty. For every 100 of these families, only 23 received cash assistance from TANF, down from 68 families when TANF was enacted in 1996. (See Figure 5.) This “TANF-to-poverty ratio” (TPR) is near its lowest in the program’s history. If in 2019 TANF had the same reach as its predecessor did in 1996, it would have reached 3.1 million families living in poverty in 2019 — 2 million more families than it actually reached.

There is also extreme and growing variation in TPRs by state, making TANF access largely dependent on where families live. In 2019, the TPR ranged from 70 in California to 4 in Louisiana. These geographic disparities reflect — and can widen — racial inequities in the program: Black children are likelier and Latino children are somewhat likelier than white children to live in states with the lowest TPRs. Forty-one percent of Black children live in states with TPRs of 10 or less, compared to 33 percent of Latino children and only 28 percent of white children.

Benefit levels for those who actually receive TANF are extremely low. In 2020 the maximum TANF benefit for a family of three in every state is at or below 60 percent of the poverty line and benefits are below 20 percent in 18 states. Following a similar pattern as inadequate access, the erosion of TANF benefits has fallen more heavily on Black children: a majority (55 percent) of Black children in the country live in a state with benefits at or below 20 percent of the poverty line, compared to 41 percent of Latino children and 40 percent of white children.

Benefit levels were not high in most states when TANF was first created, and most states have allowed inflation to erode their benefits even further. In all but three states, the real (inflation-adjusted) value of TANF cash benefits has fallen since 1996, and in a majority of the states, TANF cash benefits are worth at least 25 percent less today than in 1996. The decline has been most dramatic in the South, where historical racism has limited the amount of cash provided to families.[15] About 3 million Black children (31 percent of the national total) live in four Southern states — Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas — that have benefits at or below 17 percent of the poverty line for a family of three, or about $308 per month in 2020. Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina have not increased benefits since the early 1990s.[16]

Far from being a model program, TANF is long overdue for reform. More of the same will not result in better outcomes for families – and especially for children who grow up in a family that does not have enough income to make ends meet. Research shows the negative impacts of adversity on school readiness, educational achievement, and later economic success, as well as higher rates of chronic physical and mental health problems from childhood through adulthood — compelling evidence for why addressing TANF’s failures is important for all of us.[17]