States can and should use the flexibility and financial resources they have to support parents receiving income support from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program and allow them to participate in two- and four-year college programs. Helping families access college opens new possibilities for participation in state and local economies by reducing barriers to meaningful, long-term employment that many parents experiencing financial crises face. It also can disrupt the occupational segregation that occurs from TANF’s emphasis on “work first,” which results in parents being placed quickly into the same unstable, low-paying jobs that often led them to TANF in the first place.

All too often, TANF parents are denied the opportunity to pursue post-secondary education or are required to meet such onerous requirements that they choose not to pursue those opportunities, limiting their future employment prospects. Only about 10 percent of TANF parents have completed any education beyond high school.[1]

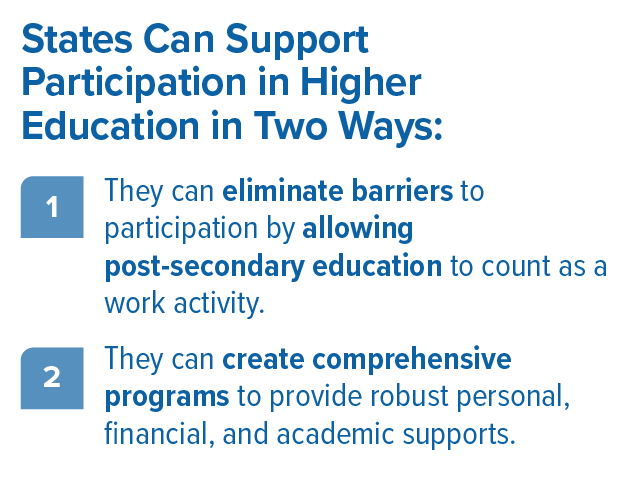

States can support participation in two- and four-year colleges in two ways. First, they can eliminate barriers to participation by allowing post-secondary education to count as a work activity, even when it does not count toward meeting the state’s federal work participation rate requirement. Second, they can create comprehensive programs to provide robust personal, financial, and academic supports to help parents enroll in college and successfully complete a two- or four-year degree.

Before discussing each of these options in detail, we present findings from studies showing the positive outcomes associated with earning a college degree and describe the flexibility states have under current law.

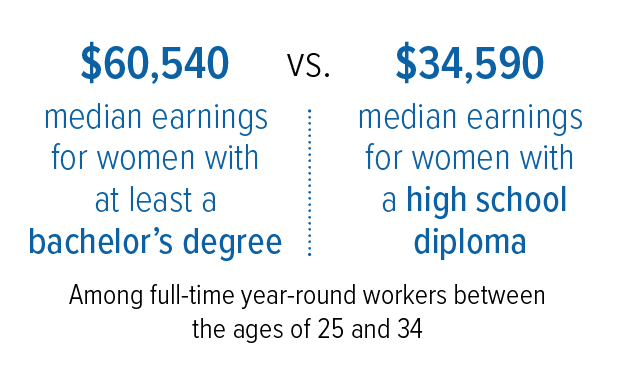

Post-secondary education improves outcomes for people across gender, race, and income. College degrees can be especially valuable to people who experience significant labor market disadvantages. In 2021, median earnings of bachelor’s degree recipients aged 25 and older with no advanced degree and working full time were $29,000 higher (65 percent) than those of high school graduates. Among full-time year-round workers between the ages of 25 and 34, median earnings for women with at least a bachelor’s degree were $60,540, compared with $34,590 for those with a high school diploma.[2] College graduates from families with incomes below 185 percent of the federal poverty line earn 91 percent more over their careers than high school graduates from the same income group.[3] Single mothers with bachelor’s degrees earn on average $1.1 million over their lifetime, which is about $625,000 more than the lifetime earnings of single mothers with a high school diploma.[4]

Although median earnings increase for people who complete a college degree regardless of their gender, race, or ethnicity, a college degree does not erase earnings disparities. For example, median earnings for Black workers with an associate or bachelor’s degree are 19 percent and 21 percent less than for white workers, respectively.[5] Between 2019 and 2021, the median earnings of women aged 25-34 with a bachelor’s degree and working full time year-round were almost 20 percent less than the earnings of men.[6] Attending college does not appear to reduce current earnings, which are the same for students regardless of whether they graduated from college before or after the age of 25.[7]

Enrollment in college is substantially lower among people with lower incomes and students from marginalized communities — groups that TANF is ideally positioned to reach. About 89 percent of students from families with high incomes attend college, compared to 64 percent of students from middle-income families and 51 percent of students from families with low incomes.[8] Black and Hispanic students are also less likely to enroll in college than white high school students. In 2020, the shares of Black, Hispanic, and white recent high school graduates enrolling in college within a year were 57, 62, and 68 percent, respectively.[9] Some factors that lead to lower rates of college attendance include the wealth gap, poorly funded high schools, limited access to college counselors, and growing up in a family where no one has a college degree.

In addition to increased earnings, higher education offers many non-monetary benefits such as better individual and public health protection and outcomes.[10] People with a college degree are more likely than those without to benefit from workplace mentoring and to develop close relationships with co-workers.[11] They also have more stable marriages and are less likely to be unemployed.[12]

Some of these non-monetary benefits were evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mortality rates among people in jobs deemed “essential” at the beginning of the pandemic — many of which do not require education beyond high school — were higher than among workers in occupations that afforded greater flexibility to work from home; these occupations also are more likely to be held by people with education beyond high school. Researchers posit that the higher concentration of Black and Hispanic workers in occupations that did not allow this flexibility was one factor contributing to their higher mortality rates during the beginning of the pandemic.[13]

The benefits of attending college also extend to the next generation of high school students. Students whose parents received a college degree are more likely to attend college themselves.[14] And adults with at least one college-educated parent are far more likely to complete college than adults with parents without college degrees. Seventy percent of adults aged 22 to 59 with at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree or more have completed a bachelor’s degree themselves compared to only 26 percent of those who do not have a college-educated parent.

This pattern is consistent across demographic groups, although the difference among white adults is greater than for Black or Hispanic adults. For white adults, the difference between those with and without a college-educated parent is 72 percent versus 20 percent, respectively, compared to 57 percent versus 21 percent for Black adults and 58 percent versus 15 percent for Hispanic adults.[15]

Increased earnings allow parents to accumulate wealth that makes attending college less costly for the next generation. The median wealth of households headed by a first-generation college graduate is 40 percent lower than that of households headed by a second-generation college graduate. This difference is due, in part, to the amount of college debt that first-generation college students accumulate.[16]

States Can Expand Access to Higher Education for TANF Parents Under Current Law

States have the flexibility to support TANF participants who want to attend post-secondary education programs. However, only a few states have done so, due in part to perceived constraints in the federal work participation rate requirements and TANF’s historical emphasis on “work first.”[17]

The focus on “work first” results in parents leaving TANF for the same kinds of jobs — jobs that pay low wages, offer unpredictable hours and few (if any) benefits, and often are unstable — that led them to need assistance from TANF in the first place. This focus emerged from TANF’s racist history, in which Black women have been portrayed as lazy and needing to be forced to work.[18] Early studies also showed that “work first” programs produced better results, but later studies with longer follow-up showed that programs that supported education and training produced better results.[19]

Not all TANF parents want to pursue post-secondary education, but for those who want to pursue it, the impact on their family’s long-term economic security can be significant. To help parents maximize their potential and to mitigate some of the harm perpetuated by long-held stereotypes, states can and should use existing flexibility to encourage and support participation in two- and four-year college degree programs.

Federal law requires states to engage parents in work, as defined by the state. States are allowed to decide what parents are asked to do and how their participation is monitored. However, most states have aligned their definitions of work activities with the restrictive requirements parents must be engaged in to meet the state’s work participation metric, known as the work participation rate (WPR).[20]

The problem with this approach is that the WPR requirements significantly restrict participation in post-secondary education as well as developmental education programs that can prepare parents for participation in higher education programs. Participation in “vocational education” (which includes higher education) can only count for 12 months in a parent’s lifetime, and states can only engage 30 percent of their work participants in this activity. In 2021, states were nowhere near this cap: only about 7,000 of the 172,000 TANF parents (4 percent) met their federal work requirements through participation in vocational education — the category most often used to capture participation in higher education; two-thirds of those in that category were from California.[21]

Although the program activities that “count” toward meeting the WPR are restrictive, states have substantial flexibility to allow participation in higher education as a work activity because of how the WPR is calculated. States are held accountable for meeting two rates — 50 percent for all families and 90 percent for two-parent families, adjusted for the decline in the state’s TANF caseload since 2005. (The base year for this calculation will change to 2015 in fiscal year 2025.)

Every year, the Office of Family Assistance in the Department of Health and Human Services — the federal office that manages TANF — calculates a target WPR for each state. The rate states achieve is calculated as the share of “work-eligible” individuals[22] participating in “countable” work activities for their required number of hours (20 or 30 hours depending on the age of the youngest child in the household). To avoid a penalty, the rate a state achieves must be equal to or greater than the target rate.

In 2021, the latest year for which data are available, because of a caseload reduction credit, many states had substantial room to allow and support participation in activities that do not count toward the WPR.[23] The amount of flexibility states have may be reduced some but will not be eliminated when the base year for the calculation changes to 2015.

Several factors keep states from expanding the work activities in which parents can participate. First, even though most states are meeting their WPR with significant room to engage parents in activities that will not count toward the WPR, administrators remain fearful of facing a penalty, which starts at 5 percent of a state’s block grant and can go as high as 21 percent.

These fears persist even though few states have ever had to pay anything more than a very small penalty, in part because states that fail to meet the rate are able to engage in a corrective action plan. Also, many states have not assessed and updated their TANF policies since they were put in place more than 25 years ago, when the assumption was that the states would have to meet the full rate because caseload declines were not necessarily anticipated. And some states incorrectly assume that they are required to engage parents only in the activities that count toward the WPR.

There are also misunderstandings about what the evidence does and does not show about pure “work first” models and the value of higher education, and these misunderstandings discount how higher education can be a very good investment in long-term stability for some parents receiving TANF. Finally, some TANF policy remains driven by the idea, often with roots in racism, that parents will only seek work if forced to do so.

States Using Flexibility to Expand Access Provide Models for Other States

Some states and large cities, recognizing the benefits of allowing parents receiving TANF to attend college, have expanded the activities parents can participate in to meet their work requirement. They also have implemented processes to reduce the paperwork burden and eliminate the stigma parents often face when attending college.

- Minnesota passed legislation in 2014 to increase access to education for TANF students. The legislation eliminated limits on participation in education and training activities and allows students to pursue four-year degree programs while receiving TANF.[24]

- Nebraska has since 1996 allowed parents to meet work requirements through post-secondary education. Students can pursue two-year, post-secondary education while counting these activities as core work activities.

- New York City initially approves participation in higher education programs for up to 12 months. Thereafter, students who are in good academic standing are permitted to continue attending full time even after the 12-month lifetime maximum is reached.

- Rhode Island passed legislation in 2022 that permits parents who have completed one year of education or training in community college to attend a second year as their sole employment activity.

- Virginia passed legislation in 2022 that exempts parents pursuing post-secondary education from the state’s work program.

Several states that support parents attending college have implemented processes to reduce the barriers created by onerous reporting requirements.

- Maine passed legislation that counts study hours as three times the number of hours of classroom instruction and does not require the hours to be scheduled or supervised. The legislation also deems a participant as having met the participation requirements if they choose to attend school less than full time in order to improve their academic performance, improve their attendance, or better meet the needs of their family.

- Pennsylvania reduced the reporting burden on participants by placing most of that reporting responsibility on employment, training, and educational institutions that have a contract with the state to provide vocational education training for TANF parents. Staff can rely on self-reported hours of participation as long as they have ongoing contact with the participant, access to course credits and grades, or some other mechanism in place for monitoring course progress.

- Vermont recently passed legislation that allows participation in a broader set of work activities than it counts for purposes of meeting the WPR. To reduce the paperwork burden on parents, including those pursuing higher education, the state only reports hours of participation in unsubsidized and subsidized employment and satisfactory attendance at high school or a GED program for parents who have not completed high school.

Putting policies and procedures in place that allow TANF parents to pursue two- or four-year degrees is a necessary first step. But research on the experiences of students from households with lower incomes suggests that more comprehensive support is needed to promote successful completion, expanded employment opportunities, and increased earnings.

A 2019 survey of two- and four-year college students found that 39 percent of the students responding to the survey reported being food insecure in the prior 30 days, 46 percent reported being housing insecure, and 17 percent reported being homeless in the previous year.[25] Student parents, who account for 22 percent of all undergraduate students, have worse outcomes, on average, than students who are not caring for children. Student parents often work full time while attending school and face significant challenges in carving out adequate time for studying given parenting demands and other household and family responsibilities.[26]

Fortunately, there is growing evidence that providing comprehensive supports to students with low incomes can increase their chances of earning a degree and increasing their earnings. These findings come from rigorous experiments conducted in community colleges that serve large numbers of students from families with low incomes, many of whom are the first in their families to attend college. While none of these studies focus on programs designed explicitly to support parents receiving TANF who attend two- or four-year colleges, the results suggest that it should be possible to design programs that increase the likelihood that TANF parents who pursue college will be successful in their endeavors.

A study of the Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) at the City University of New York found that after three years, 40 percent of students randomly selected to participate in ASAP graduated compared to just 22 percent of the students not selected to participate in the program; at six years, graduation rates were 51 percent for those selected to participate compared to 40 percent for those not selected.[27]

A similar support program implemented in three community colleges in Ohio also found significant positive outcomes in students earning degrees and increasing earnings. The program model required students to enroll full time, encouraged them to take developmental courses immediately, provided comprehensive support services such as enhanced advising and financial support to help students meet participation requirements, and offered blocked courses and condensed schedules. After three years, 35 percent of the students assigned to participate in the program had earned degrees compared to 19 percent of students not assigned to participate. After six years, the share earning a degree increased to 42 and 26 percent, respectively.

In the sixth year, the average earnings of all students assigned to the program (including those who were not working) were $1,948 (11 percent) higher than the $17,626 earned by students not assigned. Among students with earnings, the average earnings for those assigned to participate were about $3,000 higher than those not assigned to participate.[28]

At least five states — California, Kentucky, Maine, Pennsylvania, and Vermont — operate programs that are specifically designed to support TANF or former TANF parents participating in two- and four-year higher education programs. While none of these programs have been rigorously evaluated, they show how TANF agencies can design programs to support students who choose to attend two- or four-year colleges.

These programs address the supportive services that many TANF parents need, such as child care, transportation, and assistance with ancillary education costs (such as books and required facility and lab fees). Most of the programs also help parents navigate college requirements and provide academic counseling and support; several also provide on-campus support. In these five states, college attendance satisfies a parent’s work requirement. Most of the programs also have dedicated staff who help participants navigate enrollment in courses, apply for financial aid, and access resources available to all students enrolled at the college or community college.

- California Community Colleges, CalWORKs Parents Education Program.[29]TANF parents (known in California as CalWORKs parents) can enroll in any community college in the state. Community colleges receive TANF funds to develop or redesign curricula, link courses to job placement through work experience and internships, redesign basic education and English as a Second Language classes so they can be integrated into community college offerings, and expand the use of telecommunications in the new offerings. Community colleges also receive funds to provide campus-based case management and special services, such as child care and transportation assistance as well as other assistance like counseling, tutoring, or mentoring to help participants meet their educational goals. TANF parents enrolled in community college programs do not have to meet the 20-hour core work requirement, but the program must lead to a degree (or certificate) and the student must demonstrate “satisfactory progress” in the program.

- Kentucky Ready to Work (RTW)[30] provides comprehensive services to help TANF parents enroll and succeed in the state’s community and technical colleges. Campus-based coordinators provide and/or facilitate a comprehensive network of support services for TANF parents including outreach and recruitment, education and career planning and coaching, tutoring, case management, advocacy, and retention strategies. A key component of the program is the development and support of work-study opportunities, which allow a student to work up to 30 hours per week without impacting the amount of their TANF benefit. Coordinators also help the RTW participants access all supportive services (such as transportation and child care) and other resources available to them through other agencies. RTW has been operating as a partnership between the state human services agency and the community and technical college system since 1988.

- Maine’s Parents as Scholars (PaS)[31] program provides services such as transportation, child care, ancillary funding outside of tuition such as books and other supplies, and financial aid application assistance to parents enrolled in TANF pursuing either a two- or four-year degree. The goal of PaS is to open up new employment opportunities that have the potential to increase students’ earnings. Students cannot have a bachelor’s degree in a field with available jobs or the ability to earn at least 85 percent of Maine’s median income for their family size. PaS operates as a “separate state program” funded solely with state maintenance-of-effort dollars, which means that the time spent in the program does not count against a family’s federal 60-month time limit. This makes it possible for parents to take longer to complete their degree if extra time is needed.

- Pennsylvania’s Keystone Education Yields Success (KEYS)[32] program funds student facilitators at 14 community colleges to provide personalized academic guidance, enrollment assistance (including applying for financial aid) and funds to cover registration fees, school supplies, and clothing for 24 months. Students must enroll in a career-specific program of study; general studies such as liberal arts are not permitted. Students may receive an extension beyond the 24 months if they face extenuating circumstances.

- Vermont’s Post-Secondary Education (PSE)[33] program is available to TANF parents and other students with dependent children with incomes under 150 percent of the federal poverty level who are pursuing a two- or four-year degree. Case managers help eligible students set goals, secure funding for tuition, apply for monthly income support, secure child care and transportation assistance, and secure school supplies. Students enrolled in PSE must agree to work no more than 20 hours per week so they can focus on their studies. Students participating in PSE may also be eligible for emergency rental assistance, free weatherization services, and participation in a special initiative that helps mothers learn how to better manage their stress.

States have the flexibility and the resources they need to help parents who want to pursue a college degree. The payoffs could be significant, not only for current TANF parents but also for future generations.

States can use state and federal TANF funds to provide comprehensive supports to TANF parents pursuing higher education, but most states spend very little to support participation in any work activity. In 2021, states reported spending $800 million — 2.6 percent of all spending — on education and training activities. They spent $1.4 billion — 4.6 percent of all reported spending — on additional work activities, such as job search and job readiness and employment counseling and coaching. States reported spending just $329 million — 1.1 percent of all reported expenditures — on work supports such as transportation assistance, textbooks, or clothing needed for work. They reported spending $5.9 billion on child care for current and former TANF parents as well as parents who have never been on TANF but are in need of assistance to cover child care costs. Most of the funds states spend on child care support working families rather than those participating in education and training activities.

By 2021, states had accumulated almost $6.2 billion in unspent federal TANF funds. While the priority for those funds should be increasing income support to help TANF parents meet their basic needs, some of those funds could also be used to provide comprehensive supports to TANF parents who want to attend college to expand their employment options and increase their earnings.

Some states use TANF funds to provide college scholarships, but those programs are not always targeted to students in families with very low incomes and mostly operate in states that do not permit TANF parents to attend college. Those funds could be redirected to support TANF parents or other parents with very low incomes who are attending or want to attend college.