Chairman Whitehouse, Ranking Member Grassley, and members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify before you this morning at this important hearing.

I am Peggy Bailey, Vice President for Housing and Income Security at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan research and policy institute in Washington, D.C. In this testimony, I will discuss the pressing housing affordability crisis affecting people with the lowest incomes. I will recommend policies, with a focus on rental subsidy programs that help people afford housing, that will move us toward the goal of ensuring that everyone in this country is able to afford safe, stable housing in a community of their choice.

New data analysis from the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University (JCHS) finds that the number of households paying more than one-third of their income on housing (both rental and single-family housing) has grown to 42 million, the highest level since 2011.[1] Of these, 22.4 million are renters.

Examining the data more deeply, JCHS found that more than half of cost-burdened renter households — 12.1 million — pay more than 50 percent of their income on rent, which is an all-time high. And while affordability has worsened for renters at all income levels, households earning less than $30,000 per year have the worst affordability issues, with 80 percent of these renters paying more than one-third of their income on rent.

A growing number of people can’t afford homes at all. On a single night in January 2023, 653,000 people were experiencing homelessness in the United States, a 12 percent increase from a year earlier and the highest number ever recorded.[2]

Typically, renters who must pay very high shares of their income for housing have to divert money away from other necessities to keep a roof over their head, such as by going without needed food, medicine, clothing, or school supplies. As those unmet needs pile up, families often find themselves one setback — a cut in their work hours or an unexpected bill — away from eviction or homelessness. When families with low incomes receive help meeting these basic needs, they put those resources back into the economy by buying food, clothes and other essentials.[3]

Affordable housing also directly impacts employment and job creation. People can’t work in communities where they can’t afford housing.[4] More affordable housing options can help employers attract employees, making it a key tool to address local labor shortages. In addition, increasing funding to renovate or create affordable housing is a job creator. Similar to other infrastructure projects like road construction, improving housing and increasing supply requires people to build the development, manage and maintain the building, and attend to other housing-related needs.[5]

Finally, stabilizing a family in housing they can afford helps them engage in the workforce in a more consistent and productive way. The family can live closer to their job and not have concerns about evictions which, when they happen, cause them to move — maybe farther from work — or spend time away from work looking for a new home.[6] Plus, stable, good-quality housing improves people’s physical and mental health, making them more productive and happier overall.

The most pressing housing challenge has been a long-standing structural problem: millions of people simply don’t have enough income to afford market rents. A surge in rents between 2020 and 2022 was accompanied by an increase in incomes but not enough to close this persistent gap.

This often is characterized as a problem caused by the lack of supply of units. While supply is an issue, it is important to recognize that most people have a place to live and are not seeking to move; they simply struggle to afford their current residence. One reason supply investments alone are rarely enough to enable the lowest-income households to more easily afford housing is that these households typically can’t afford rent set at a high enough level for an owner to cover the ongoing cost of operating and managing housing.

For example, the average extremely low-income renter household had an income of $11,451 in 2021.[7](The Department of Housing and Urban Development, HUD, defines extremely low income as below the federal poverty line or 30 percent of the local median income, whichever is higher.) Government programs and private-sector owners and lenders often consider housing affordable if rent and utilities cost no more than 30 percent of household income, which for this household works out to $286 a month. Many households, including those most at risk of homelessness, have much lower incomes and can afford even less in rent.

But in 2021 the average rental unit’s operating cost was $566 a month, according to an industry survey.[8] The “operating” cost excludes the cost of building the unit, buying the land, or major renovations — or ongoing payments on loans taken out to cover those costs — and any profit to the owner. Consequently, even if development subsidies pay for the full cost of building housing, rents in new units will generally be too high for extremely low-income families to afford without the added, ongoing help rental assistance can provide. This example is theoretical and highlights a unit with the cheapest rent possible. That isn’t reality. Most new units in the last few years are meant for higher-income renters, with rents at or above fair market levels. (HUD defines Fair Market Rents as the 40th percentile rent for units within a given metropolitan area or nonmetropolitan county).[9]

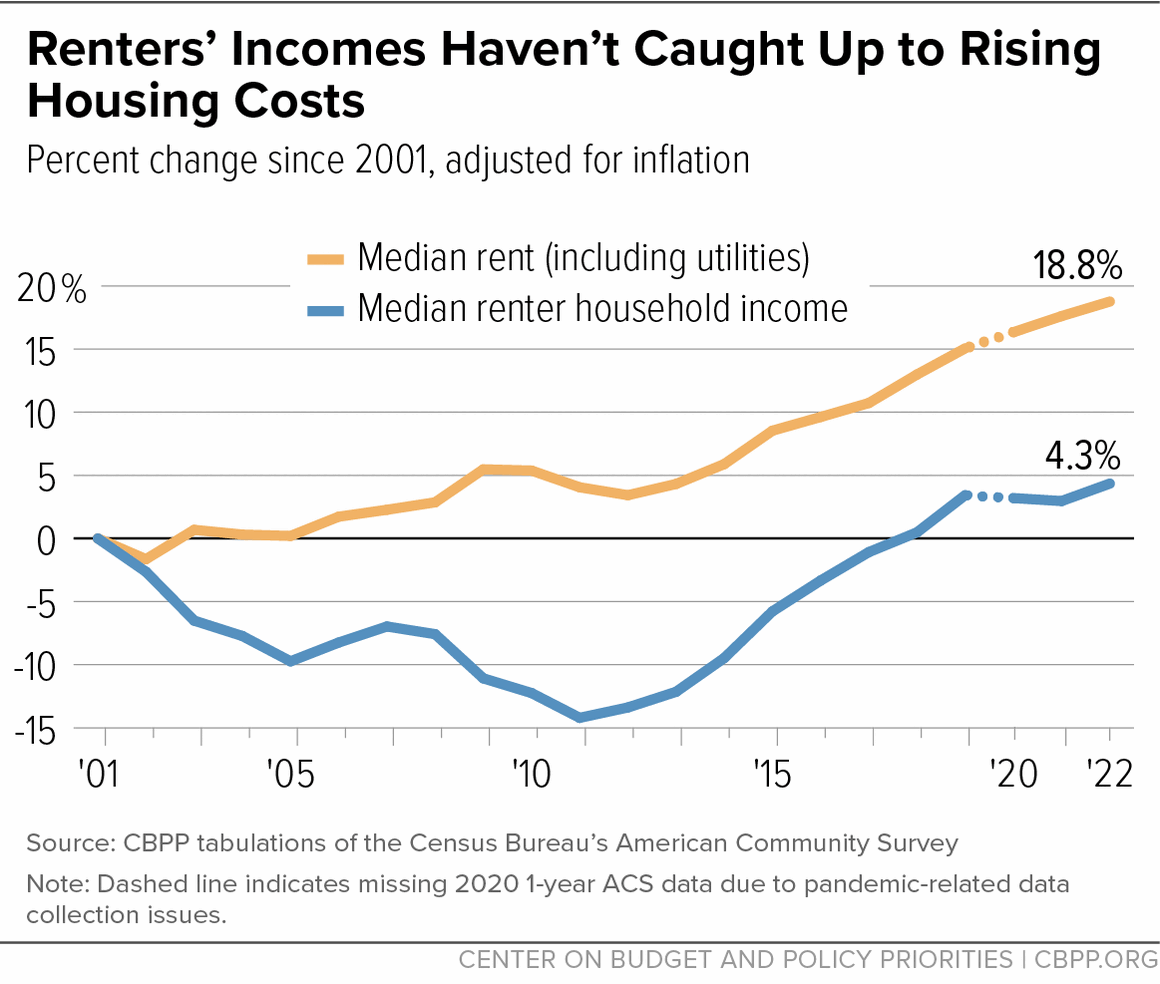

The growth in rents has moderated since late 2022 — in some markets they are still increasing but at a more modest rate, while in other markets they are decreasing. [10] However, housing costs remain high for many families, and renters’ incomes haven’t kept pace. Median rent rose nearly 19 percent from 2001 to 2022 while median renter household income only increased 4 percent, after adjusting for the overall inflation rate. (See Figure 1.) This persistent gap between rents and income leaves many families with few affordable housing options.

Difficulty affording housing is heavily concentrated among households at the bottom of the income scale. Nearly everywhere in the country, rents are too high to be affordable to people with the lowest incomes, including low-paid workers,[11] low-income families with children, and older adults and people with disabilities who have low fixed incomes.[12]

Nearly two-thirds of households earning less than $30,000 paid over half their income in rent in 2022, and these households are far more likely than higher-income households to experience homelessness and other housing-related hardship.[13]

Due to a long history of racial discrimination in housing and other areas, these problems are disproportionately concentrated among people of color. Over 63 percent of people in low-income households that pay more than half their incomes for housing are people of color.[14] Renters of color, particularly Black renters, are also more likely to face eviction than white renters. Despite making up less than one-fifth of all renters, Black renters account for over half of those affected by eviction filings in a given year, putting them at higher risk of losing their homes and experiencing homelessness.[15] Black people make up nearly 13 percent of the U.S. population but were 37 percent of unhoused people in 2023.[16]

Other people of color also disproportionately face homelessness due to the gap between their incomes and the cost of housing. Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders experience the highest rates of homelessness, followed by American Indians and Alaska Natives, Black people, and Latine people.[17] People with disabilities are also overrepresented. Over half of adults and heads of households and 40 percent of youth staying in a shelter reported having a disability in 2021.[18] And 1 in 3 unhoused people experienced chronic homelessness in 2023, meaning they both had a disability and experienced extended or repeated homelessness.[19]

In addition to people who are unhoused, too many people who currently reside in existing affordable housing units, such as public housing and other federal subsidized multi-family developments, are living in dilapidated conditions that are increasingly unsafe and unhealthy.[20] Unfortunately, their income levels and lack of affordable housing options make it difficult for them to move to a better housing unit. Their assistance is tied to the property and isn’t portable to a new place. This leaves people trapped in substandard housing.

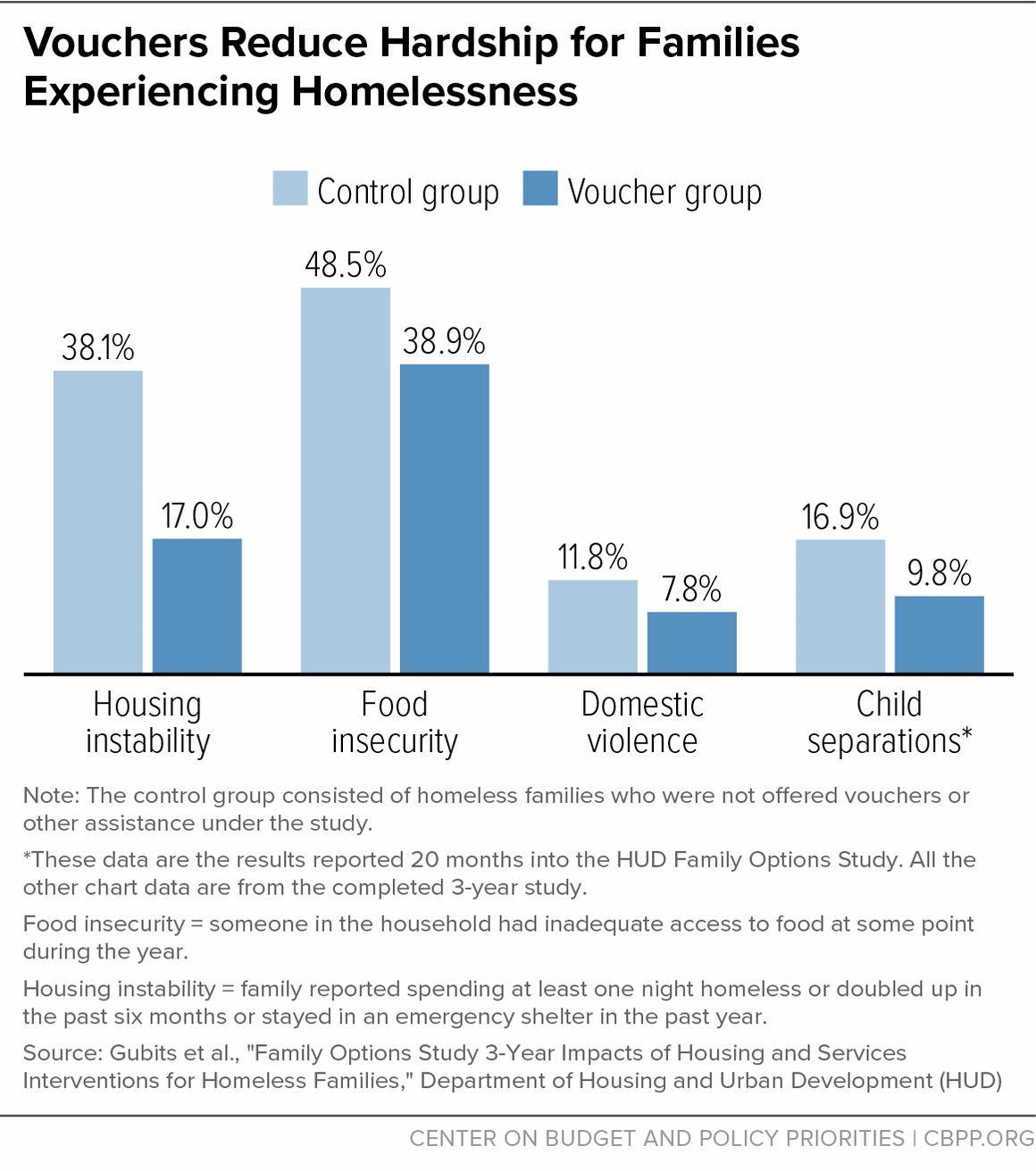

Tenant-based rental assistance, like the assistance provided through the Housing Choice Voucher program, is a large piece of the solution for the problems explained above, research shows. Housing vouchers sharply reduce homelessness, overcrowding, and housing instability. (See Figure 2.) And because stable housing is crucial to many other aspects of a family’s life, those same studies show numerous additional benefits to vouchers. Children in families with vouchers are less likely to be placed in foster care, switch schools less frequently, experience fewer sleep disruptions and behavioral problems, and are likelier to exhibit positive social behaviors such as offering to help others or treating younger children kindly. Among adults in these families, vouchers reduce rates of domestic violence, drug and alcohol misuse, and psychological distress.[21]

Expanding rental assistance can also sharply reduce racial disparities in poverty rates and a range of housing hardships. For example, one study estimated that providing vouchers to all eligible households would lift 9.3 million people above the poverty line, using a measure of poverty that counts in-kind benefits such as rental assistance as income. Poverty rates would drop for all racial and ethnic groups but most among Black and Latine households, reducing the gap in poverty rates between Black and white households by one-third and the gap between Latine and white households by nearly half.

Similarly, people of color would be particularly likely to benefit from reducing homelessness, overcrowding, and evictions and other housing instability as a result of additional vouchers.[22] Moreover, resources for tribal housing programs, such as HUD’s Indian Housing Block Grant (IHBG), would be particularly helpful for reducing housing hardship in tribal areas. American Indians and Alaska Natives living on tribal lands face higher rates of overcrowding and substandard housing,[23] compared to the national average for all households.

Out of respect for their sovereignty, tribal nations receive federal housing funding through flexible grants such as IHBG instead of through programs like Housing Choice Vouchers, Project-Based Rental Assistance, or public housing. However, the funding in the IHBG is currently far too low to address the acute housing needs in these communities so more investment is critical.

Pandemic Relief Proved Federal Investments Can Succeed and Are Needed

The successes of housing relief that policymakers enacted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrate the impact of making significant investments in programs that promote housing stability. As the pandemic took hold, it became clear that housing assistance would be a critical piece of the response. Federal, state, and local governments acted to mitigate harm and help keep people housed during the public health emergency. This included the creation of the Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) program and funding for 70,000 Emergency Housing Vouchers (EHVs) for people experiencing or at risk of homelessness and survivors of domestic violence and trafficking. As a result, evictions dropped below historical rates and homelessness mostly held steady during the initial pandemic response until resources, particularly in the ERA program, ran out. [24]

Congress provided a total of $46.5 billion for the ERA program, which has helped more than 6.5 million households with rent or utilities. This level of resources devoted to housing during a crisis was unprecedented and, combined with eviction moratoria and other diversion efforts, prevented more than 1 million evictions nationwide, by one estimate.[25]

Even after the federal eviction moratorium ended in August 2021, ERA, eviction diversion programs, and other assistance programs helped reduce evictions in 2021 to levels at half the historical rate. As remaining local eviction moratoria expired and more ERA programs began pausing or ending their programs, eviction rates increased in 2022 but remained below the historical rate until the end of 2022 when many communities had depleted their ERA funds.[26]

Although the population eligible for ERA was fairly broad — people with incomes at or below 80 percent of the area median income who experienced a loss of income and faced housing instability — the program succeeded in reaching the people facing the greatest risk of eviction. For example:

- Some 64 percent of ERA recipients had extremely low incomes, which was double their share of those eligible, an analysis of equity in ERA conducted by the Government Services Administration’s Office of Evaluation Sciences found.[27]

- ERA recipients, as compared to the overall target population, were more likely to be Black, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander renters — groups that face the highest eviction risks.[28] Beyond the context of the pandemic, Black women are the group most likely to face eviction because of differences in wages, historic and ongoing housing discrimination, and other factors such as likelihood of children in the house, so ERA’s effectiveness at reaching this group is important.[29]

The success of ERA demonstrates the importance of investing in housing. First, it shows that when resources are provided, communities will use them effectively to help more people afford stable housing. Second, and more importantly, the uptake of ERA shows how many people are experiencing or one setback away from housing instability. The ERA program was designed to help people recover from financial shocks caused by the pandemic, and a permanent program would undoubtedly strengthen the country’s housing assistance system. But this short-term, temporary relief is no substitute for significant investment in well-targeted, long-term rental assistance and other measures to close the gaps between rents and incomes, especially for people facing the greatest economic hardships.

The American Rescue Plan funded 70,000 EHVs in recognition that some households would need longer-term assistance, especially given pre-pandemic national trends in housing insecurity. The EHV program is designed to reach people facing the greatest barriers to stable housing. An early analysis of the program found that those receiving EHVs on average have an income of $11,349, which is about 27 percent less than the typical voucher household.

As of July 2022, the EHV program had the fastest leasing rate of any previous HUD housing voucher program.[30] This program’s success shows that additional rental assistance can be successfully used, even in tight markets. But because of its limited size, the program only reaches a small share of those who need ongoing assistance to afford rent.

Rental assistance is by far the most direct, effective way to address the nation’s most severe housing problems. While all federal rental assistance (this includes programs administered by both HUD and the U.S. Department of Agriculture) helps 10 million people in 5 million households afford housing, it only reaches about 1 in 4 households in need.[31] Policymakers should sharply expand rental assistance, ultimately building toward a program that guarantees assistance to every person with a low income who needs it.

Congress must:

- Maintain the current number of households receiving rental assistance and begin to expand rental assistance to reach all families who need it. This includes utilizing the mandatory side of the budget for rental assistance expansion to ensure that funding adjusts as costs and needs rise and prioritizing expansion to reach all people with the lowest incomes first;

- Make larger and streamlined investments that increase supply of affordable housing;

- Increase investment in fair housing solutions and tenant protections; and

- Invest to revitalize public housing and other aging affordable housing developments.

Protect and Expand Rental Assistance

Rental assistance programs are typically funded as if housing is optional for families, not a necessity. With only 1 in every 4 eligible households receiving rental assistance, the level of investment clearly does not match need. The spending caps under the debt ceiling agreement set tight limits for non-defense discretionary funding, which makes it challenging to maintain the number of families receiving assistance as rent rises, let alone to make the investments needed to meaningfully reduce the large number of families who face very high rent burdens that strain the family and all too often result in housing instability, eviction, and homelessness. Indeed, the funding levels for the voucher program in both the House and Senate appropriations bills — which were initially set before the cost needs of the program were fully known — would result in a loss in the number of families receiving rental assistance.

A loss in already limited assistance would hamper efforts to address increases in homelessness, evictions, and a lack of affordable housing and would likely increase the harm that people across the country face due to high rent costs. People left without vouchers — who are disproportionately Black, women, children, and people with disabilities — would be at high risk of eviction and potentially homelessness.

Therefore, in the short term, Congress should ensure a final 2024 appropriations legislation fully funds existing Housing Choice Vouchers by providing a significant increase over 2023 funding levels. CBPP estimates that the cost to retain existing vouchers is about $2.3 billion above 2023 levels, assuming that part of the shortfall is covered using housing agencies’ reserves. The 2024 funding bills passed by the House Appropriations Committee and the Senate increase funding, but not by enough to cover the cost of all existing vouchers.

Congress should also adequately fund other rental assistance programs, such as public housing, as well as Homeless Assistance Grants, which help people connect with emergency shelters and the services they need to obtain and maintain stable housing. These programs are all critical pieces of reducing the harms that come from housing instability.

Going forward, simply maintaining current levels of assistance won’t address unmet need. Ensuring everyone has stable housing requires a level of investment and commitment that’s better suited for mandatory funding that adjusts as need rises. Any rental assistance program that guarantees assistance to every person with a low income who needs it would have to be mandatory, rather than funded through annual discretionary appropriations, to ensure that benefits can be provided to all eligible households, similar to other mandatory programs like Medicaid and Social Security. This would ensure that enough funding is available to cover the cost of this assistance (which may be higher or lower than policymakers can project in advance, due to unpredictable factors such as market rents, family incomes, and the share of eligible households who participate).

Assuming phasing in such a program would be necessary, it should be developed using an income-based (rather than population-based) approach. An income-based expansion strategy that guarantees rental assistance first to people with the lowest incomes would ensure that people with the greatest needs are prioritized and would be the most equitable approach. It would also benefit from broad support among a variety of renter advocates and housing stakeholders because a wide range of groups of people at greatest risk of housing instability would benefit, including people of color, veterans, people experiencing homelessness, young adults, families with children, people with disabilities, and older adults.

Our current approach to addressing homelessness of pairing rental assistance with supportive services, is sound and decreased homelessness between 2007 and 2016. But homelessness started rising again in 2017 as more people were forced into homelessness each year due to the lack of deeply affordable housing.[32]

Population-based strategies to address homelessness while coping with constrained resources has negatively impacted progress. As homelessness began to rise in 2017, policymakers began to rely more heavily on interventions targeted to particular subgroups, like veterans, older adults, or children exiting foster care, as a way to cope with limited resources. These interventions helped those reached, but they often left behind groups more heavily affected by homelessness.

Notably, racial and ethnic demographics of various subgroups may not match the overall racial and ethnic makeup of people experiencing housing insecurity and homelessness, as seen with veterans and older adults experiencing homelessness.[33]For example, these efforts did little to address the substantial over-representation of Black people among the unhoused population. As we move ahead with efforts to expand rental assistance, we should craft efforts that target new resources to people based on their income. Doing so will make sure that those most in need get help.

Policymakers should also seek to improve rental assistance to make it easier for families to use it to rent housing of their choice. This should include reforms to the existing voucher program, such as streamlining housing quality inspections and allowing subsidy funds to be used for security deposits. In addition, direct rental assistance — which is provided directly to tenants rather than through landlords — should be tested both through privately funded local pilots (as HUD has proposed) and a national demonstration.[34]

Increase and Streamline Funding for New Affordable Housing

Many parts of the country face serious housing shortages, estimated at a total of 3.8 million units by a 2021 Freddie Mac study,[35] that drive up home prices and rents and limit the housing options available to families and individuals. In allocating new resources and implementing policies to make funding streams align more easily with each other and the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), policymakers should prioritize investments in programs that benefit the lowest-income people and other underserved groups, including the National Housing Trust Fund, Public Housing Operating and Capital Fund, and tribal housing programs. In addition to expanding LIHTC, policymakers should continue to promote ways to reform LIHTC to encourage states and developers to make rents affordable to people with incomes well below the program’s eligibility limit.

Fair Housing and Tenant Protections

Our country’s history of discriminatory housing policy is long and harmful housing discrimination is still a problem today. This is why ensuring renters have robust, enforceable rights against discrimination, coercion, and abuse is a critical pillar of addressing the affordable housing crisis. This includes funding for education, enforcement, and testing to ensure owners and other actors are abiding by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which prohibits discrimination based on race, color, sex (including gender identity and sexual orientation), disability, national origin, religion, and familial status.

Another key aspect is implementation of the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule that charges HUD grantees with actively removing barriers to housing choice, overcoming patterns of segregation, and creating inclusive communities. Such proactive and defensive measures should be combined with broader federal, state, and local protections for all renters that help address imbalances of power created in the owner-tenant relationship, including increased access to legal representation during disputes such as eviction hearings.

Governments at all levels and housing agencies must work together to preserve the existing affordable housing stock while also improving the properties and families’ overall experience. This includes redeveloping existing public housing properties through HUD tools such as the Rental Assistance Demonstration program; finding ways to incentivize Low Income Housing Tax Credit property owners to keep their developments affordable once their initial contract term ends; investing in redevelopment resources for properties that receive HUD assistance such as the Project-Based Rental Assistance program; and incentivizing landlords to rent to families with low incomes — especially families receiving Housing Choice Vouchers. The estimated cost to revitalize existing public housing units alone is at least $70 billion.[36] Even more is needed to maintain the entire existing affordable housing stock.