The House-passed bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would effectively end the Medicaid expansion and radically restructure Medicaid by converting it to either a per capita cap or block grant. Together, these changes would cut federal Medicaid spending by $839 billion over ten years and reduce enrollment by 14 million people by 2026, relative to current law.[1] Some Senate Republicans, including Senators Pat Toomey and Mike Lee, are seeking additional changes to the per capita cap that would dramatically expand those already highly damaging cuts.[2]

The House Republican health bill (the American Health Care Act, or AHCA) would end Medicaid’s federal-state financing partnership, in which the federal government pays a fixed percentage of state Medicaid costs — on average, 64 percent today. Instead, beginning in 2020, federal funding would be capped at a set amount per beneficiary. The overall cap would equal federal Medicaid spending per beneficiary in 2016, rising each year by a slower rate than the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) current projection for Medicaid spending per beneficiary. That would cut federal Medicaid spending, with the cuts growing each year. (States would also have the option of converting Medicaid to a block grant for children, adults other than seniors and people with disabilities, or both.)

To compensate for this large cost shift, states would have to raise taxes, cut other budget areas like education, or as is far likelier, cut Medicaid spending. But Medicaid is already highly efficient, with per-beneficiary costs that are lower than (and growing more slowly than) private insurance.[3] So states would likely have to make cuts that seriously harm beneficiaries, like restricting eligibility, reducing services, cutting payments to providers, or a combination of all three approaches to rationing care. Moreover, under the House bill, these federal funding shortfalls would be even greater if health care costs grow more quickly than anticipated due to a public health emergency, development of a costly new prescription drug, or changing demographics, as states would be responsible for 100 percent of all costs above the cap.

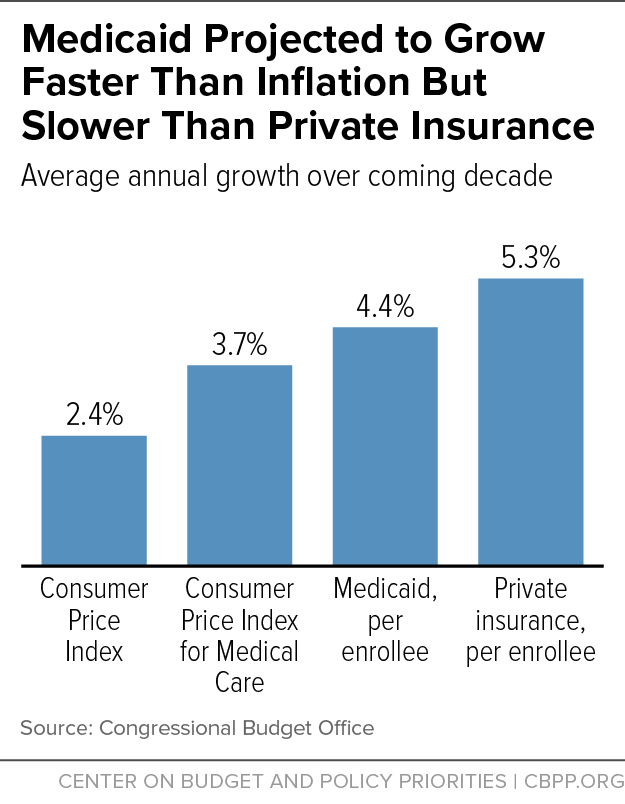

While CBO has not specified how much of the AHCA’s $839 billion in Medicaid cuts result from its per capita cap, CBO clearly expects the cap to produce significant federal savings. CBO estimates that overall Medicaid per-beneficiary costs would grow annually by 4.4 percent, on average, over the next ten years.[4] (That’s considerably slower than in private insurance, where CBO projects spending per person to rise by 5.3 percent annually between 2016 and 2025; see Figure 1.[5]) But the per capita cap would take a state’s Medicaid spending per beneficiary in fiscal year 2016 and increase it annually through 2019 only by the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index (M-CPI), which CBO expects to grow by 3.7 percent per year.[6]

Starting in 2020, the AHCA would establish different per-beneficiary caps for different groups: the caps for children, expansion adults, and other adults would continue rising annually by the M-CPI, while the caps for seniors and people with disabilities would rise by the M-CPI plus 1 percentage point. Each year, states receive a fixed amount of overall federal funding based on each of these caps and enrollment in each beneficiary group.

Senators Toomey and Lee are pushing to further cut the annual growth rate for the per capita cap to general inflation (CPI-U). That would be certain to sharply increase the Medicaid spending cuts under the AHCA’s per capita cap, as CBO estimates the CPI-U will grow only by 2.4 percent annually — far below CBO’s projected growth in Medicaid per-beneficiary costs of 4.4 percent.[7] That would produce even larger cuts to federal Medicaid funding for states. This greater cost shift, in turn, would lead states to make even more damaging cuts to eligibility, benefits, and provider payments over time than under the House-passed bill.

Senators Toomey and Lee have reportedly argued that it’s reasonable to reduce the growth rate because Medicaid per-beneficiary costs grew slightly slower than CPI-U between 1999 and 2015, averaging just 2.0 percent based on National Health Expenditure data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. But this reasoning is not sound, as it overlooks the following important points:

- The unusually low growth rate between 1999-2015 is not expected to continue, as the CBO projections indicate. In significant part, the past growth rate reflected the shifting of prescription drug costs for dual eligibles (people eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare) from Medicaid to Medicare when the Medicare Part D drug benefit took effect in 2006. In addition, overall prescription drug costs grew at historically low rates during this period as a number of costly drugs went off-patent, fewer blockbuster drugs came to market, and utilization of generic drugs increased. That trend has since reversed, with growth in drug costs accelerating in the last two years due to the new drugs treating Hepatitis C and large cost increases for specialty drugs. Moreover, in coming years, new but costly medical breakthrough drugs to address diseases such as Parkinson’s will likely come to the market, further driving up drug spending.

- It ignores the impact of population aging, which will accelerate Medicaid spending growth per beneficiary. The share of seniors who are 85 and older will rise substantially in future decades as the huge baby-boom population moves into “old-old” age.[8] Seniors aged 85 and older have much higher health care costs than young elderly people because they have more serious and chronic health problems and are likelier to require nursing home and other long-term services and supports. In 2011, average Medicaid costs were more than 2.5 times higher for beneficiaries 85 and older than for those aged 65 to 74.[9]

The AHCA ignores this basic fact. Under the bill, each state’s funding cap per senior beneficiary would effectively be based on the state’s spending per senior beneficiary in 2016, when the share of elderly beneficiaries aged 85 and over was significantly smaller than it will be when the boomers reach old-old age. This serious flaw in the House bill’s per capita cap formula virtually guarantees that the formula will be insufficient and will cause increasingly serious difficulties for states over time. Lowering the already inadequate annual adjustment factors would make the squeeze on state Medicaid programs and state budgets still more severe.

- It does not address the unanticipated costs states may experience. As noted, under the House bill’s per capita cap, states are responsible for 100 percent of costs above the cap. That would include costs stemming from public health emergencies like the opioid epidemic, which has driven up Medicaid costs among the states most deeply affected.

- The AHCA’s per capita cap would have cut federal Medicaid funding even during the period of very slow spending growth. A recent Brookings analysis found that if the bill’s per capita cap had taken effect in 2004 based on states’ spending in 2000, states would have experienced a federal spending cut of $17.8 billion in 2011 (see Table 1). As a percent of federal Medicaid funding, that would be equivalent to a roughly $41 billion cut in 2026.

Moreover, the $17.8 billion cut would have roughly doubled if Medicaid per-beneficiary cost growth had been just 1 percentage point higher between 2000 and 2011. And, because the per capita cap wouldn’t account for state-by-state variation in growth in per-beneficiary costs, some states would have seen far bigger cuts than the national average. For example, four states would have had to increase their Medicaid spending in 2011 by over 40 percent to compensate for the cut in federal Medicaid funding.[10] The analysis also found that states with lower per-beneficiary spending in the base year experienced faster cost growth in subsequent years and were more likely to experience shortfalls in federal funding. A Kaiser Family Foundation analysis produced similar results, estimating the impact of the version of AHCA reported by the House Budget Committee.[11]

| TABLE #1 |

|---|

| Federal Medicaid spending cut in 2011 |

$17.8 billion |

| Percentage cut to federal Medicaid spending in 2011 |

6.5 percent |

| Equivalent cut to federal Medicaid spending in 2026 |

$41 billion* |

| Average increase in state spending needed to compensate for federal spending cuts in 2011 |

11.3 percent |

| Number of states that would have to increase state spending by more than 20 percent |

13 |

| Number of states that would have to increase state spending by more than 40 percent |

4 |

Senate Republicans should not just reject any effort to deepen the House bill’s highly damaging Medicaid cuts. They should entirely reject all of its harmful Medicaid cuts, including its provision to effectively repeal the Medicaid expansion and convert Medicaid to a per capita cap or block grant. Otherwise, tens of millions of low-income children and families, seniors, people with disabilities, and other adults would be at severe risk of becoming uninsured or going without needed care.