Any Year-End Tax Legislation Should Expand Child Tax Credit to Cut Child Poverty

End Notes

[1] Letter to Majority Leader Schumer, Speaker Johnson, Minority Leader McConnell, and Minority Leader Jeffries, November 2, 2023, https://documents.nam.org/TAX/2023%20Tax%20Priorities%20Sign-On%20Letter%20FINAL.pdf

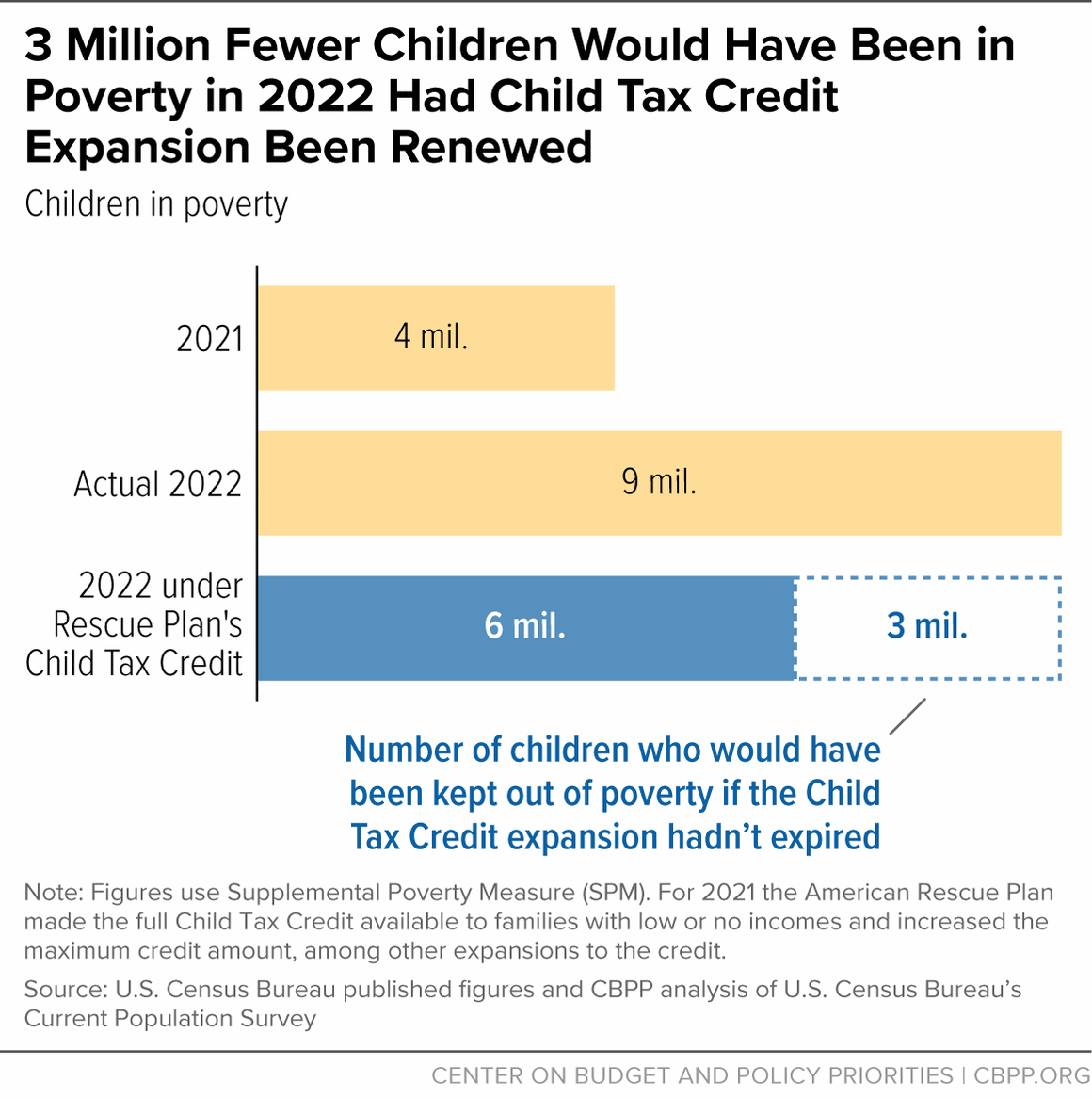

[2] Figure is based on the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), the more comprehensive of the government’s two poverty measures, which counts tax credits and non-tax benefits as family resources. Under the SPM, a two-adult, two-child family renting in an average-cost community in 2022 was considered “poor” if its resources were below $34,500.

[3] Sharon Parrott, “Record Rise in Poverty Highlights Importance of Child Tax Credit; Health Coverage Marks a High Point Before Pandemic Safeguards Ended,” CBPP, September 12, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/press/statements/record-rise-in-poverty-highlights-importance-of-child-tax-credit-health-coverage. CBPP analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau's March 2023 Current Population Survey.

[4] Laura Weiss, “Some Republicans crack open door to child tax credit compromise,” Roll Call, August 10, 2023, https://rollcall.com/2023/08/10/some-republicans-crack-open-door-to-child-tax-credit-compromise/.

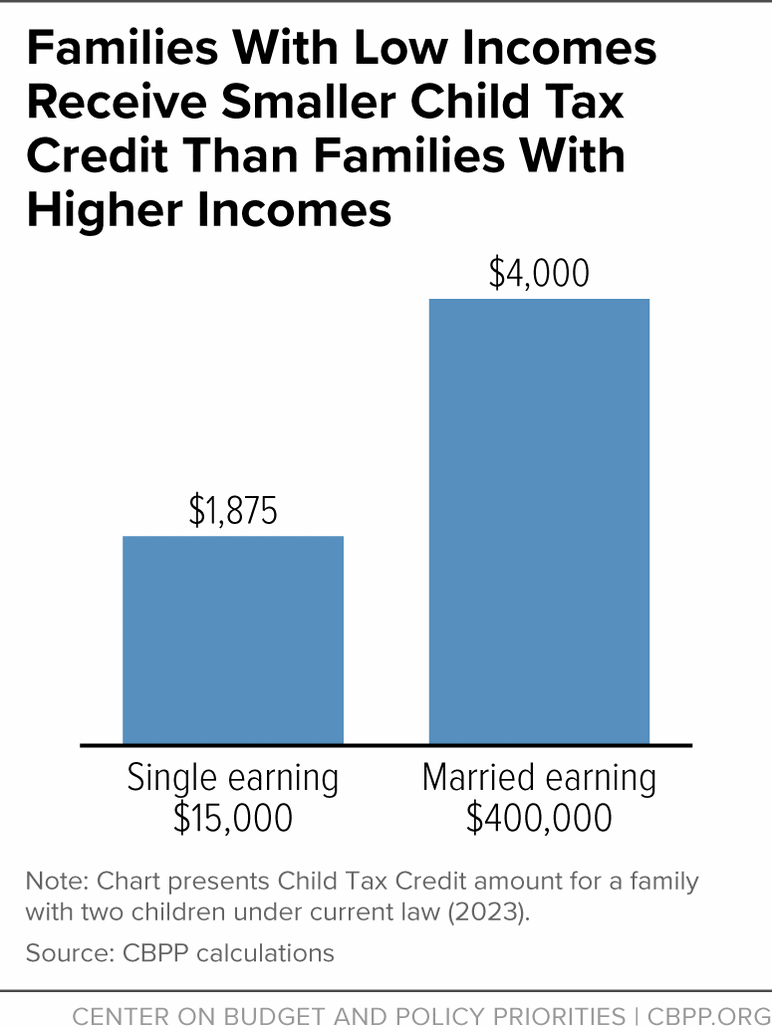

[5] Another feature of the credit, the refundability cap, enacted in the 2017 tax law, limits the credit amount that families can receive that exceeds their pre-credit federal income tax liability. In 2023, the refundability cap is $1,600 per child.

[6] A seemingly technical point is important to focus on: the “phase-in” of the Child Tax Credit is 15 cents on the dollar despite that fact that this family has two children. While the overall Child Tax Credit is calculated on a “per-child” basis, it is not phased in that way for families with low incomes. Instead it is phased in at the same 15 cents on the dollar whether a family has one, two, or more children. This design flaw warrants special attention.

[7] Tax Policy Center estimate for 2022.

[8] Shares of children by race or ethnicity from Kris Cox et al., “Top Tax Priority: Expanding the Child Tax Credit in Upcoming Economic Legislation,” CBPP, updated June 12, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/top-tax-priority-expanding-the-child-tax-credit-in-upcoming-economic; share of children in rural counties from Chuck Marr et al., “Year-End Tax Policy Priority: Expand the Child Tax Credit for the 19 Million Children Who Receive Less Than the Full Credit,” CBPP, updated December 7, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/year-end-tax-policy-priority-expand-the-child-tax-credit-for-the-19-million.

[9] The Rescue Plan also allowed families to claim their 17-year-old children for the credit for the first time. All changes were made for one year, 2021.

[10] In 2021, the child poverty rate reached a record low of 5.2 percent. We estimate that, without the Rescue Plan’s expanded credit, the child poverty rate would have been about 8.1 percent in 2021. Chuck Marr et al., “Policymakers Should Expand Child Tax Credit in Year-End Legislation to Fight Child Poverty,” CBPP, updated October 20, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policymakers-should-expand-child-tax-credit-in-year-end-legislation-to-fight.

[11] Jake Schild et al., “Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Household Spending: Estimates Based on U.S. Consumer Expenditure Survey Data,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 31412, June 2023, https://www.nber.org/papers/w31412.

[12] Parrott, op. cit.; CBPP analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s March 2023 Current Population Survey.

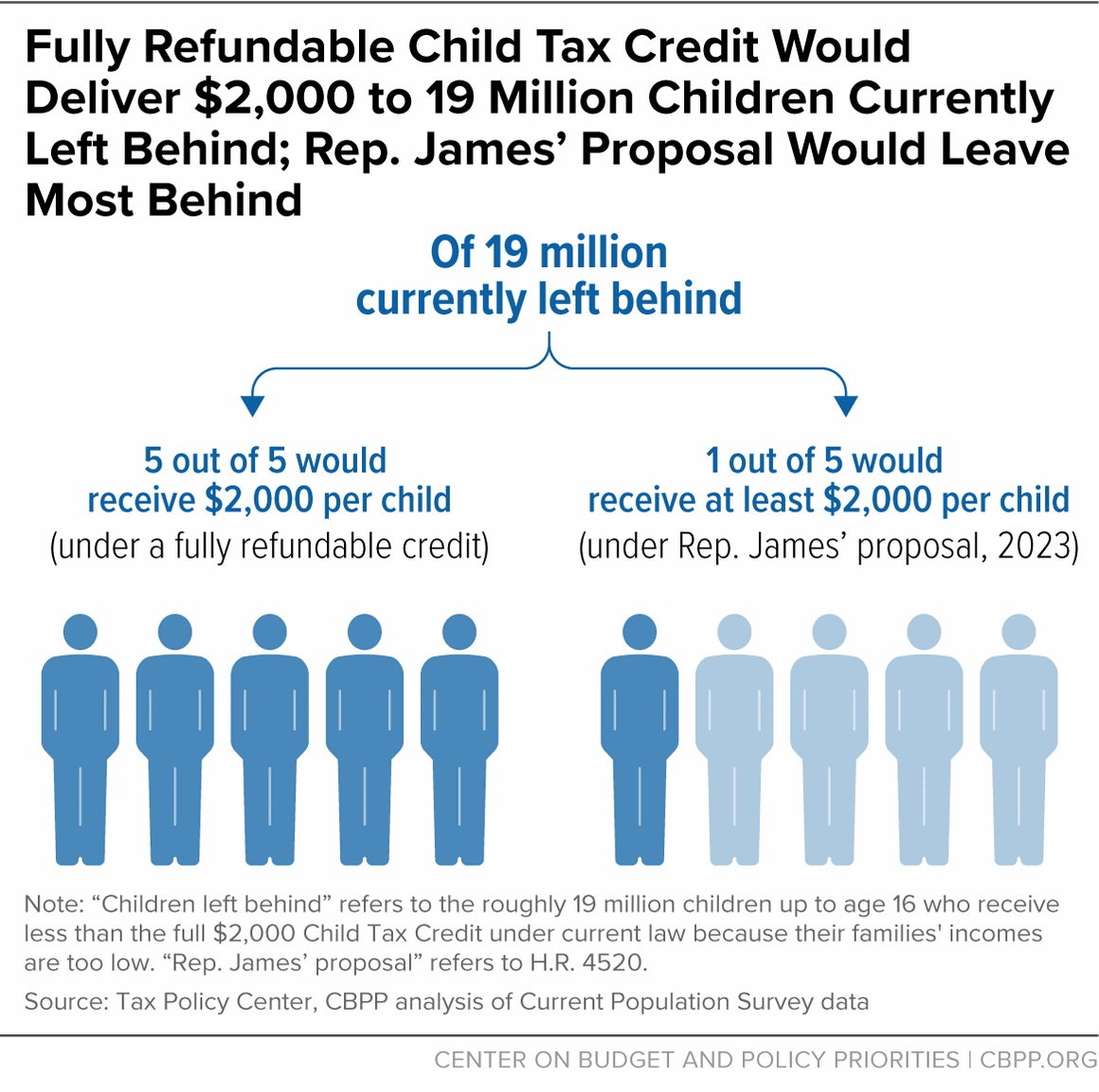

[13] The proposal recently introduced by House Republicans, led by Rep. John James, would provide the larger maximum credit amount to families earning up to $200,000 and $400,000, for single and married parents respectively. Reignite Hope Act of 2023, H.R.4520, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/4520.

[14] For example, raising the maximum credit to $4,500 for children up to age 5 and $3,500 for children aged 6-16 with no other design changes would lift only about 200,000 children above the poverty line in 2023, based on our projections.

[15]Without other design improvements, indexing the maximum credit to inflation would also only help children who already receive the maximum credit. That would leave behind the 19 million children who receive less than the full amount under current law and would do little to reduce child poverty.

[16] Senator Rubio and Rep. Hinson introduced a similar proposal, which included the same phase-in improvements and maximum credit increase, along with additional provisions. It would also continue to deny millions of children in families with low incomes the full credit.

[17] This estimate does not reflect the effects of making 17-year-olds eligible for the credit. Projections for 2023 are based on CBPP analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s March 2019 Current Population Survey. We start with data from 2018 because that year’s employment rate resembles the employment rate in 2023 more closely than do other recent years. We use 2023 tax parameters; adjust earnings to 2023 dollars by calculating growth in wages and salaries per non-farm job using Bureau of Economic Analysis data on wage and salary growth through 2022, CBO wage and salary projections for 2023, Bureau of Labor Statistics data on nonfarm payroll employment through 2022, and CBO payroll employment projections for 2023; and adjust all other income for changes in the consumer price index through 2022 and CBO projections of inflation in 2023. SNAP benefits, which are factored into the poverty calculation, are adjusted to account for the Thrifty Food Plan re-evaluation in October 2021.

[18] Senator Rubio and Rep. Hinson’s bill also makes these changes. Both Republican proposals would also expand the credit to 17-year-olds. H.R. 4520, op. cit.

[19] Our projections for 2023 show that a fully refundable $2,000 credit would lift roughly 1.5 million children out of poverty, while the Republican proposal would lift only an estimated 700,000 children out of poverty. (The former estimate reflects a fully refundable $2,000 credit for children up to age 16; the latter estimate reflects the full Republican proposal, which makes 17-year-olds eligible for the credit.) Compared to the phase-in improvements or the maximum credit increase alone, the full Republican proposal would have a larger impact on child poverty due to the interaction of these component parts, but it still would have a much smaller impact than a fully refundable $2,000 credit. Furthermore, the children lifted above the poverty line by the Republican proposal would largely be those who already receive the full $2,000 credit under current law or close to it. The Republican proposal would do little for families with the very lowest incomes, lifting fewer than 50,000 children above one-half of the poverty line (“deep poverty”) in 2023. Such deep poverty is particularly troubling given the evidence showing that income during childhood makes a significant difference to children’s later health, academic achievement, earnings, and other outcomes.

[20] The Rescue Plan’s Child Tax Credit expansion would lift roughly 3 million children out of poverty in 2023, based on our projections.

[21] In 2021, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that a fully refundable $2,000 credit would cost roughly $12 billion per year through 2025. This is the most recently available estimate, but the estimated cost may change if JCT scores this proposal again. Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions of Title XIII - Committee on Ways and Means, of H.R. 5376, The ‘Build Back Better Act,’” JCX-46-21, November 19, 2021, https://www.jct.gov/publications/2021/jcx-46-21/.