- Home

- Federal Tax

- About 16 Million Children In Low-Income ...

Executive Summary: About 16 Million Children in Low-Income Families Would Gain in First Year of Bipartisan Child Tax Credit Expansion

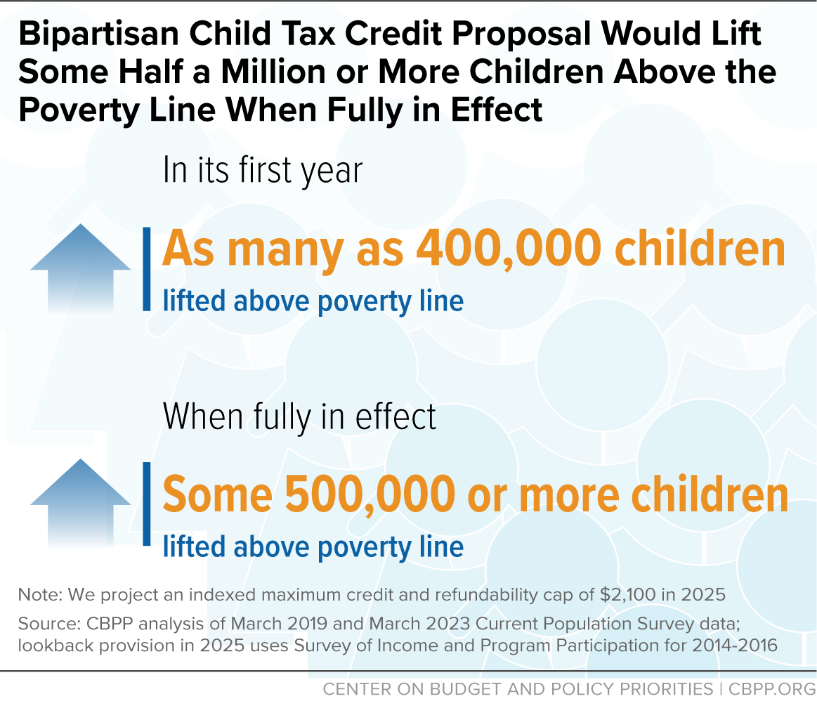

Half a Million or More Children Would Be Lifted Above the Poverty Line When Fully in Effect

The bipartisan Child Tax Credit expansion in the tax bill negotiated by Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden and House Ways and Means Committee Chair Jason Smith takes an important step toward making the credit work for children in families with low incomes. While smaller than the American Rescue Plan credit expansion that expired at the end of 2021, the proposal’s top priority is getting more of the credit to most of the roughly 19 million children who currently get a partial credit or none at all because their families’ incomes are too low. The bipartisan proposal pairs corporate and small business tax provisions with Child Tax Credit improvements that cost a similar amount, reportedly about $35 billion for each set of proposals. With the exception of a modest indexing proposal, all of the benefits from the Child Tax Credit improvements go to children left out of the full credit because their families’ incomes are too low.[1]

The expansion would be in effect for three years. While modest in size, the proposal would have a significant impact. In the first year, more than 80 percent of the roughly 19 million children under 17 in families with low incomes who don’t now get the full credit would benefit — about 16 million children.[2] This includes nearly 3 million children under age 3. (See Table 1 for state-by-state estimates of the 16 million children overall and by race and ethnicity.)

In the first year, the proposal would lift as many as 400,000 children above the poverty line and make an additional 3 million children less poor as their incomes rise closer to the poverty line. These poverty-reducing effects would increase over time. When the proposal is fully in effect in 2025, it would lift some half a million or more children above the poverty line and make about 5 million more less poor. (See Figure 1.) This would mark the beginning of a much-needed reversal of the sharp rise in child poverty that occurred in 2022, following the expiration of the Rescue Plan expansion of the Child Tax Credit and other COVID relief measures.

The proposal would benefit children of all races and ethnicities. Overall, more than 1 in 5 children under 17 would benefit in the first year. The expansion would particularly help Black, Latino, and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) children, whose parents are overrepresented in low-paid work due to historical and ongoing discrimination and other structural barriers to opportunity. More than 1 in 3 Black children, more than 1 in 3 Latino children, 3 in 10 AIAN children under 17, and roughly 1 in 7 white children and Asian children under 17 would benefit from the proposal.

The proposal would deliver a meaningful income boost to millions of families in the first year. For example, consider a parent who has a toddler and a second grader and earns $15,000 working as a food server. In the first year, the family’s Child Tax Credit would increase by $1,725, from $1,875 to $3,600.

Half of the roughly 16 million children who would benefit under the proposal in the first year live in families who would gain $630 or more. For nearly 40 percent of children who would benefit, their family’s gain would be $1,000 or more, and 25 percent of children are in families who would gain more than $1,400 in the first year. The gains for low-income families with more than one child — roughly three-quarters of children in low-income families are in this group — would be particularly large. Among children who live in families with more than one child and who would benefit, half are in families who would gain $1,000 or more in the first year.[3] For families who don’t now get the full credit because their incomes are too low, the gains would be larger when the proposal is fully in effect in 2025.

Three important structural improvements to the Child Tax Credit’s design drive these gains:

- Moving to a “per-child” phase-in to ensure low-income families receive the same credit for each of their children, as higher-income families already do;

- Increasing and then effectively ending in tax year 2025 the lower maximum credit amount (known as the “refundability cap”) that only limits the credit for families with low incomes; and

- Allowing families to use their earnings from either the current tax year or the year before when calculating the Child Tax Credit to help protect them from a drop in their credit if their earnings declined — because they lost a job, faced health or caregiving needs, or welcomed a new child, for example (this is called a “lookback” provision and would start in tax year 2024).

In addition, the bipartisan proposal would index the maximum amount of the Child Tax Credit, which is currently set at $2,000. This change would not take immediate effect and is expected to first increase the maximum credit in 2025 to $2,100. Unlike the improvements discussed above, indexing is broad-based and would benefit families with higher incomes, but it also would provide benefits to some families with low and moderate incomes as well.

As part of the bipartisan compromise, the package includes three corporate tax cuts that reverse, in whole or in part, provisions originally enacted in the 2017 tax law to offset some of the cost of that law’s large cut in the corporate tax rate.[4]

Specifically, the compromise would return to immediate expensing of research and experimentation costs (R&E) for domestic research expenditures, return to full expensing for capital investments, and provide more generous deductions for interest expenses. As we highlighted previously,[5] each of these provisions has issues from our perspective — both in terms of substantive policy and gimmicky timing effects that mask their true costs — but these compromises were necessary to get a bipartisan deal. Both the corporate provisions and the Child Tax Credit provisions would be in place for three years — for tax years 2023, 2024, and 2025 — expiring at the end of 2025 like many tax provisions from the 2017 tax law.

The package includes several additional modest provisions. For example, it increases the amount of investments that small businesses can immediately expense and a restores an expansion of the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit that was in effect from 2018-2021 and would expand affordable housing units for low- or moderate-income households.

In a positive development, the package is offset by making certain changes to the administration and enforcement of the Employee Retention Credit, a temporary credit first enacted as a COVID relief measure in March 2020 to help certain businesses continue to meet payroll obligations amid lower consumer demand. In recent months, however, the credit has faced worrying allegations of fraud and abuse.[6] The proposal would, among other changes, eliminate future claims of the credit and extend the amount of time for the IRS to undertake enforcement actions for improper claims. This bipartisan commitment to pay for this tax package is particularly important looking ahead to the larger 2025 tax debate, when policymakers will face important questions about paying for tax cuts.

This Child Tax Credit proposal is far more modest in size and impact than the Rescue Plan expansion. It is, however, well targeted. The per-child phase-in, the increase and then effective elimination of the refundability cap, and the lookback provision, which together constitute the overwhelming bulk of the Child Tax Credit proposal’s cost, would direct all of their benefits to children in low-income families who receive less than the full credit under current law. If additional improvements can be agreed to that would further increase the credit for children in low-income families, that would, of course, be preferable. But either way, Congress should seize this opportunity to pass as soon as possible a bipartisan Child Tax Credit proposal that meaningfully boosts the incomes of millions of families and significantly lowers child poverty.

| TABLE 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| About 16 Million Children in Low-Income Families — More than 1 in 5 Children Under 17 Overall — Would Gain in First Year of Bipartisan Child Tax Credit Expansion Children under 17 currently left out of the full $2,000 Child Tax Credit who would benefit from proposed bipartisan Child Tax Credit expansion in the first year, by state, race, and ethnicity | |||||||

| Total | Latino | White | Black | Asian | American Indian or Alaska Native | Another race or multiple races | |

| Total U.S. | 15,900,000 | 6,227,000 | 4,875,000 | 3,315,000 | 458,000 | 451,000 | 715,000 |

| Alabama | 280,000 | 38,000 | 103,000 | 125,000 | N/A | 3,000 | 10,000 |

| Alaska | 32,000 | N/A | 9,000 | N/A | N/A | 13,000 | N/A |

| Arizona | 424,000 | 262,000 | 87,000 | 22,000 | 5,000 | 46,000 | 11,000 |

| Arkansas | 191,000 | 36,000 | 93,000 | 49,000 | N/A | 4,000 | 9,000 |

| California | 2,070,000 | 1,555,000 | 213,000 | 115,000 | 113,000 | 52,000 | 60,000 |

| Colorado | 192,000 | 101,000 | 64,000 | 11,000 | 4,000 | 9,000 | 7,000 |

| Connecticut | 119,000 | 60,000 | 27,000 | 22,000 | 4,000 | N/A | 5,000 |

| Delaware | 40,000 | 12,000 | 11,000 | 15,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| District of Columbia | 23,000 | N/A | N/A | 17,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Florida | 1,004,000 | 403,000 | 245,000 | 288,000 | 14,000 | 11,000 | 47,000 |

| Georgia | 636,000 | 161,000 | 141,000 | 291,000 | 12,000 | 12,000 | 27,000 |

| Hawai’i | 48,000 | 10,000 | 5,000 | N/A | 6,000 | N/A | 26,000 |

| Idaho | 88,000 | 25,000 | 57,000 | N/A | N/A | 4,000 | N/A |

| Illinois | 587,000 | 219,000 | 169,000 | 153,000 | 18,000 | 5,000 | 27,000 |

| Indiana | 326,000 | 61,000 | 179,000 | 59,000 | 6,000 | 2,000 | 21,000 |

| Iowa | 129,000 | 24,000 | 73,000 | 19,000 | N/A | N/A | 7,000 |

| Kansas | 136,000 | 43,000 | 66,000 | 13,000 | N/A | 3,000 | 9,000 |

| Kentucky | 235,000 | 24,000 | 158,000 | 35,000 | 4,000 | N/A | 14,000 |

| Louisiana | 316,000 | 25,000 | 91,000 | 179,000 | 4,000 | 5,000 | 12,000 |

| Maine | 39,000 | N/A | 32,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Maryland | 194,000 | 50,000 | 44,000 | 80,000 | 8,000 | N/A | 12,000 |

| Massachusetts | 182,000 | 79,000 | 57,000 | 24,000 | 11,000 | 3,000 | 10,000 |

| Michigan | 474,000 | 61,000 | 241,000 | 127,000 | 8,000 | 11,000 | 27,000 |

| Minnesota | 194,000 | 32,000 | 73,000 | 58,000 | 12,000 | 12,000 | 9,000 |

| Mississippi | 205,000 | 11,000 | 58,000 | 126,000 | N/A | N/A | 6,000 |

| Missouri | 295,000 | 30,000 | 174,000 | 64,000 | N/A | 5,000 | 21,000 |

| Montana | 46,000 | 4,000 | 30,000 | N/A | N/A | 12,000 | N/A |

| Nebraska | 80,000 | 28,000 | 34,000 | 10,000 | N/A | 3,000 | 4,000 |

| Nevada | 163,000 | 93,000 | 29,000 | 23,000 | 5,000 | 6,000 | 10,000 |

| New Hampshire | 29,000 | 4,000 | 22,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| New Jersey | 323,000 | 151,000 | 81,000 | 64,000 | 13,000 | N/A | 14,000 |

| New Mexico | 140,000 | 97,000 | 18,000 | N/A | N/A | 28,000 | N/A |

| New York | 887,000 | 323,000 | 292,000 | 159,000 | 75,000 | 13,000 | 32,000 |

| North Carolina | 552,000 | 165,000 | 158,000 | 180,000 | 11,000 | 17,000 | 25,000 |

| North Dakota | 23,000 | N/A | 12,000 | N/A | N/A | 6,000 | N/A |

| Ohio | 575,000 | 55,000 | 306,000 | 150,000 | 8,000 | 8,000 | 50,000 |

| Oklahoma | 232,000 | 63,000 | 86,000 | 29,000 | N/A | 45,000 | 13,000 |

| Oregon | 162,000 | 59,000 | 77,000 | N/A | 4,000 | 9,000 | 9,000 |

| Pennsylvania | 506,000 | 119,000 | 228,000 | 112,000 | 15,000 | 8,000 | 27,000 |

| Rhode Island | 35,000 | 18,000 | 10,000 | 5,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| South Carolina | 282,000 | 41,000 | 84,000 | 138,000 | N/A | 3,000 | 15,000 |

| South Dakota | 41,000 | 3,000 | 17,000 | N/A | N/A | 18,000 | N/A |

| Tennessee | 385,000 | 63,000 | 184,000 | 114,000 | N/A | 4,000 | 17,000 |

| Texas | 1,921,000 | 1,332,000 | 259,000 | 245,000 | 38,000 | 18,000 | 41,000 |

| Utah | 142,000 | 50,000 | 71,000 | N/A | N/A | 5,000 | 9,000 |

| Vermont | 15,000 | N/A | 14,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Virginia | 298,000 | 61,000 | 100,000 | 106,000 | 9,000 | 3,000 | 20,000 |

| Washington | 273,000 | 111,000 | 104,000 | 17,000 | 11,000 | 15,000 | 19,000 |

| West Virginia | 87,000 | N/A | 73,000 | 6,000 | N/A | N/A | 5,000 |

| Wisconsin | 224,000 | 48,000 | 107,000 | 43,000 | 7,000 | 10,000 | 11,000 |

| Wyoming | 19,000 | 5,000 | 12,000 | N/A | N/A | 2,000 | N/A |

Notes: Children under 17 currently “left out” of the full $2,000 Child Tax Credit are those eligible for less than the full $2,000 per child under current law because their families lack earnings or have earnings that are too low. Estimates reflect a pre-pandemic economy and tax year 2023 tax rules. Figures are approximations based in part on Census Bureau data and may differ from those based solely on IRS data. Figures are rounded to the nearest 1,000. N/A indicates reliable data are not available due to small sample size. Figures may not sum to totals due to group overlap, lack of reliable data in certain cells, and/or rounding. Individuals are classified as Latino (any race); white only, not Latino; Black only, not Latino; Asian only, not Latino; American Indian or Alaska Native alone or in combination with other races, regardless of Latino ethnicity (AIAN); or another race or multiple races, not Latino. Latino includes all people of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin regardless of race. AIAN estimates are particularly sensitive to definition; AIAN figures here include those who share another race or ethnicity. (A total of 1.5 million children under 17 are identified as AIAN alone or in combination with other races, regardless of Latino ethnicity. If we apply the non-overlapping categories this report uses for other groups, about 520,000 children under 17 are considered AIAN alone, not Latino; an estimated 168,000 of these children are currently left out of the full Child Tax Credit and benefit from the expansion.)

Source: CBPP analysis of 2015 IRS Statistics of Income Public Use File for national total, allocated by state and race or ethnicity based on CBPP analysis of the American Community Survey (ACS) for 2017-2019.

End Notes

[1] For full analysis, see https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/about-16-million-children-in-low-income-families-would-gain-in-first-year-of.

[2] CBPP analysis of IRS Public Use File (PUF) for 2015, adjusted for income growth. Note that larger numbers of parents report low (rather than $0) earnings in IRS data than in Census data. Consequently, IRS data show larger numbers of families and children benefiting from the proposed Child Tax Credit expansion for families with low or moderate earnings than do analyses of Census data. This paper uses IRS data, which are generally considered more complete than Census data, where possible. Poverty estimates are based on Census data and use the Supplemental Poverty Measure.

[3] These estimates are based on IRS data. Note that because gains are larger for families with more than one child, to understand how much children typically gain, we analyze family gains each child experiences and measure the distribution of gains across children rather than across families. Median and mean gains for families without “weighting” by children understates how much a typical child’s family gains.

[4] At a cost of roughly $1.3 trillion over ten years, the 2017 law’s steep cut in the corporate tax rate — to 21 percent from 35 percent — was the most expensive part of the law and heavily benefited high-income people.

[5] Chuck Marr and Samantha Jacoby, “Policymakers Should Focus on the True Cost of an Item on Corporate Lobby’s Tax Break Wish List,” CBPP, updated November 30, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/policymakers-should-focus-on-the-true-cost-of-an-item-on-corporate-lobbys-tax-break-wish-list.

[6] IRS News Release, “To protect taxpayers from scams, IRS orders immediate stop to new Employee Retention Credit processing amid surge of questionable claims, concerns from tax pros,” September 14, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/to-protect-taxpayers-from-scams-irs-orders-immediate-stop-to-new-employee-retention-credit-processing-amid-surge-of-questionable-claims-concerns-from-tax-pros

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work:

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work:

Recent Work:

Recent Work:

Areas of Expertise