- Home

- Economy

- Testimony Of Jared Bernstein, Senior Fel...

Testimony of Jared Bernstein, Senior Fellow, Before the House Budget Committee

I appreciate the opportunity to testify before you today. The practice of American fiscal policy has become highly counterproductive in recent years, and I applaud the committee for elevating the topic.

My testimony makes the following points:

- The idea that the budget should always be in balance actually runs counter to optimal fiscal policy in an advanced, dynamic economy like ours. Instead, smart fiscal policy must be flexible, with deficits temporarily rising in recessions to support the weak economy and coming down in recoveries as the economy strengthens. Smart fiscal policy must be flexible, with deficits temporarily rising in recessions to support the weak economy.

- Elevating the goal of a balanced budget above other fiscal priorities risks doing more harm than good. The failure of European austerity — with those countries choosing fiscal consolidation in the context of weak economies — provides strong evidence to support this claim.

- In contemplating questions about fiscal policy, we must never forget the core purpose of federal taxing and spending: to provide the American people with the government services and public goods they need, want, and deserve.

- We must carry out this core purpose in a way that is fiscally responsible. At the same time, any benefits of fiscal consolidation must always be weighed against this essential government function. Are we disinvesting in critical public goods, like transportation or human capital development? Are we adequately pushing back against market failures like cyclical downturns? Are we providing those who’ve aged past their working years with adequate retirement and income security? Are we helping the least advantaged among us to meet their basic needs and to get a foothold on the ladder of upward mobility?

- The answers to these questions imply that we cannot achieve a sustainable budget, where “sustainability” includes strengthening our economy and achieving broadly shared prosperity, solely by cutting spending. Policymakers, including many on this committee, have understandably raised serious concerns about the reckless cuts engendered by sequestration. The recent Republican budget resolution calls for far deeper spending cuts, which would undermine the essential roles government should play.

- Some argue that because families and states must balance their annual budgets, the federal government must also do so. These analogies are wrong for two reasons. First, neither families nor states really have to balance their budgets; families borrow for various investments and states don’t have to balance their capital budgets, so the analogy is faulty. Second, the fiscal lesson to take from this framing of the argument is precisely the opposite of the one often drawn: the fact that states must balance their operating budgets actually provides a stronger rationale for the federal government to temporarily expand budget deficits in downturns.

- Recent Republican budget plans only achieve balance through a) excessive spending cuts that violate the principles articulated above and b) gimmicks that ignore the impact of large tax cuts that are not offset. Implementing these proposed budgets would thus gut valued investments, reduce economic security, and harm prospects for jobs and wages, while doing much less to reduce deficits and debt than proponents claim.

Optimal Fiscal Policy

What can the history of fiscal policy teach us about the optimal way to manage federal receipts and outlays?

Simply put, when the economy is on a solid growth path and resources such as labor and capital are either fully utilized or reliably moving in that direction, the federal budget should be moving toward primary balance, meaning government receipts in a fiscal year cover all government spending other than interest payments. Primary balance does not imply a zero balance. However, as long as the budget is in primary balance, the growth of the debt will match that of gross domestic product (GDP), i.e., the debt-to-GDP ratio will remain stable.

To reiterate this central point, even in strong periods of economic growth, the key fiscal goal is not a balanced budget. It is for debt to grow more slowly than GDP, i.e., for the debt ratio to fall.

On the other hand, when the economy is in recession or in a slow or weak recovery, optimal fiscal policy dictates that deficits should temporarily grow to offset such periods of cyclical weakness in the private economy.

The recent fiscal record provides a useful example of these dynamics. The deficit went up sharply to offset some of the economic damage of the Great Recession. It has since come down significantly — too quickly, as I argue below — from just below 10 percent of GDP in 2009 to below 3 percent this year. Part of that decline was due to the Great Recession fading in the rear-view mirror (good riddance!). Sure enough, the move toward primary balance — which according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) equals a deficit of about 2.7 percent of GDP this year — stabilized the debt-to-GDP ratio, albeit at high levels.

While it may surprise some members to hear that a non-zero budget deficit can lead to a declining debt burden, the historical record is clear. Between 1946 and 1979, the debt ratio plummeted from 106 percent of GDP to only 25 percent. Yet in only eight of those 33 years was the budget in balance or in surplus.[1]

I’ve described this approach to fiscal policy with the acronym CDSH: Cyclical Dove, Structural Hawk. Though not the catchiest acronym, it’s designed to capture the point that fiscal policy must be dynamic and responsive to the different stages of the economic growth cycle, a view that stands in stark contrast to the notion that a balanced budget is always desirable. That is, there are times when it is important for deficits to rise and times when it is just as important for them to fall. The fiscal problem thus is not counter-cyclical deficits, such as the ones that arose during the recent Great Recession, but rather structural primary deficits, i.e., those that persist and grow when the economy is improving.

Structural “hawkishness” must be driven by its own set of principles. First, where budget pressures exist, it is critical to determine the actual pressure points. Second, optimal solutions must ensure that cuts do not worsen poverty and inequality. It will often be preferable from the perspective of society’s well-being to raise the needed revenue to support these programs in a manner that reduces structural deficits.

Our longer-term budget pressures largely reflect three factors: our aging population, rising health care costs, and inadequate revenues to support retirement security and other budget functions that fund critical investments in public goods and protect disadvantaged populations. In this regard, assuring the long-term solvency of the Social Security and Medicare trust funds would substantially improve our long-term outlook.

In contrast, spending cuts proposed in the Republican budget that disproportionately target programs helping low-income households are misguided: these programs are decidedly not where future pressures are coming from. As a share of GDP, spending on these programs has fallen below its peak in 2010 and 2011 and, based on CBO estimates, will drop below its 40-year average by 2018 and continue declining thereafter. In fact, all non-interest spending outside of Social Security and Medicare has already fallen below its historical average and is projected to fall further under current policies.

The “cyclical dove” part of optimal fiscal policy, described more below, is to some extent embedded in our system through progressive taxation (since tax liabilities decline with real incomes) and automatic stabilizers, or counter-cyclical programs that automatically “turn on” in recessions and turn off in recoveries. Examples are Unemployment Insurance and SNAP (means-tested nutritional support), both of which performed admirably when the Great Recession hit. This system could be improved to make sure the fire trucks get to the fire sooner and don’t leave before the flames are extinguished, as my recent book, The Reconnection Agenda, explains.[2]

Faster growth is a particularly desirable way to achieve fiscal balance, as it tends to reduce spending (as people need fewer safety net services) and raise more revenues (as real income growth moves households into higher tax brackets). But growth is a complex and difficult-to-accurately-forecast phenomenon upon which policymakers cannot depend.

Optimal fiscal policy thus requires considering not just spending cuts but also revenue increases. As I discuss below, recent Republican budget proposals raise concerns in this regard, as they seek to achieve balance largely through program cuts targeting vulnerable populations in parts of the budget that are not where the long-term pressures reside. Moreover, cuts of the magnitudes they propose could worsen poverty and inequality while undermining critical investments in human capital, health, research, and a wide spate of public goods that are essential in an advanced, productive economy.

The rest of my testimony provides details on these aspects of optimal policy and the extent to which current budget plans complement or violate such an approach.

Optimal Spending Policy

While optimal fiscal policy deals with the mechanics of deficits and debt, optimal spending policy depends much more on our priorities, and different people will have different views. However, allow me to introduce a principle that may garner some agreement, even between partisans:

Public spending should be made on goods and services that the private market will either not provide, for sound business reasons, or will not provide in optimal amounts.

For example, while the private sector clearly provides some amount of educational services, it does not provide such services in a manner that is accessible and affordable to all. Thus, from the perspective of society’s well-being, it will underprovide such services. Reducing or internalizing externalities, as when a polluter does not face the costs of the environmental damage she creates, fits neatly into this framework. So do infrastructure investments in public goods that private firms will underprovide, thus reducing the economy’s productive capacity and our citizens’ safety. Defense spending is another obvious category.

Social insurance programs, like Social Security and Medicare, as well as health care to the poor and near poor (through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or CHIP), are essential ways of providing health and income security to those either in retirement or without the necessary resources to self-insure. Such programs pool risks across large and diverse populations. Similarly, the government is the only “firm” with the scope and resources to finance anti-poverty safety net programs. No private firm could set up and pay for nutritional support for low-income families or Unemployment Insurance for those hit with job loss due to demand contraction. The public sector in every advanced economy performs these functions, suggesting that they are components of optimal spending policy across diverse societies.

The key point here in the context of our balanced budget discussion is that if the government skimps on public goods — if we fail to provide ample social insurance, to maintain our bridges and public schools, to provide nutritional support for families facing hard times, for example — no other entity will step in to make up the difference. We’ll just have less retirement security, broken bridges, undernourished kids (the impact of which we now know reverberates for years), poor widows, and so on.

Optimal Counter-cyclical Policy

The “cyclical dove” part of the recommended CDSH approach refers to a critical function of the federal budget, one that may well be increasingly important over time: its ability to ramp up counter-cyclical spending when the private-sector economy temporarily slows or contracts.[3] At such times, the pursuit of a balanced budget can preclude this critical function.

Recent work by CBPP budget analyst Richard Kogan shows that as fiscal policy has evolved over time, it has increasingly played a useful stabilizing role in our economy. Poorly timed pursuit of a balanced budget would severely limit that role. Let me describe Kogan’s findings both informally and formally.

Think of the economy as a car driving down a road with numerous potholes along the way (perhaps because the fiscal authorities have neglected investment in transportation infrastructure). In the old days, the car had no shock absorbers and every bump caused a painful jolt to the passengers. But with the addition of shock absorbers, the body of the vehicle was stabilized and the passengers experienced less discomfort.

The potholes are, of course, growth shocks of the type that market economies regularly (cyclically) suffer. Before policymakers broadly accepted counter-cyclical policy, there was little in the way of fiscal reaction to cyclical shocks. That means budget deficits were smaller and less common, but growth was often lower and less stable. As Kogan’s data reveal, in the first 140 years of our nation, deficits were much rarer, smaller, and less varied (i.e., had a lower standard deviation). While some members may consider that to be a preferable record to that of more recent history, consider these facts. In the years that policymakers did not regularly tap the stabilizing function of deficit spending:

- there were 2.6 recessions per decade as opposed to 1.7 in later years;

- business cycle contractions lasted 21 months as opposed to 11 months;

- business cycle expansions lasted 25 months as opposed to 61 months;

- real GDP per person grew 1.6 percent annually as opposed to 2 percent; and

- real GDP growth per person was much less steady, with a standard deviation of 4.6 percent instead of 2.3 percent.

While I fully support the goal of putting the budget on a sustainable path as the economy strengthens, I just as strongly urge this committee not to put the nation’s households through the economically grueling process of relearning this historical lesson.

It should also be stressed in this context that because they are temporary, counter-cyclical measures by definition do not create long-term deficit pressures. As noted above, counter-cyclical deficit spending drove the deficit as a share of GDP up to almost 10 percent in 2009. Shortly thereafter, as the medicine left the system — after significantly helping the patient, I hasten to add — the deficit-to-GDP ratio began to fall, by a historically large seven percentage points of GDP between 2009 and 2014.

The key point in the context of this hearing is that temporary measures, even when they are not paid for, do not drive future years’ deficits. By 2012, the Recovery Act added only 0.4 percent to the deficit as a share of GDP. The actual culprits behind long-term, structural deficits are permanent tax cuts or spending programs that are not offset.

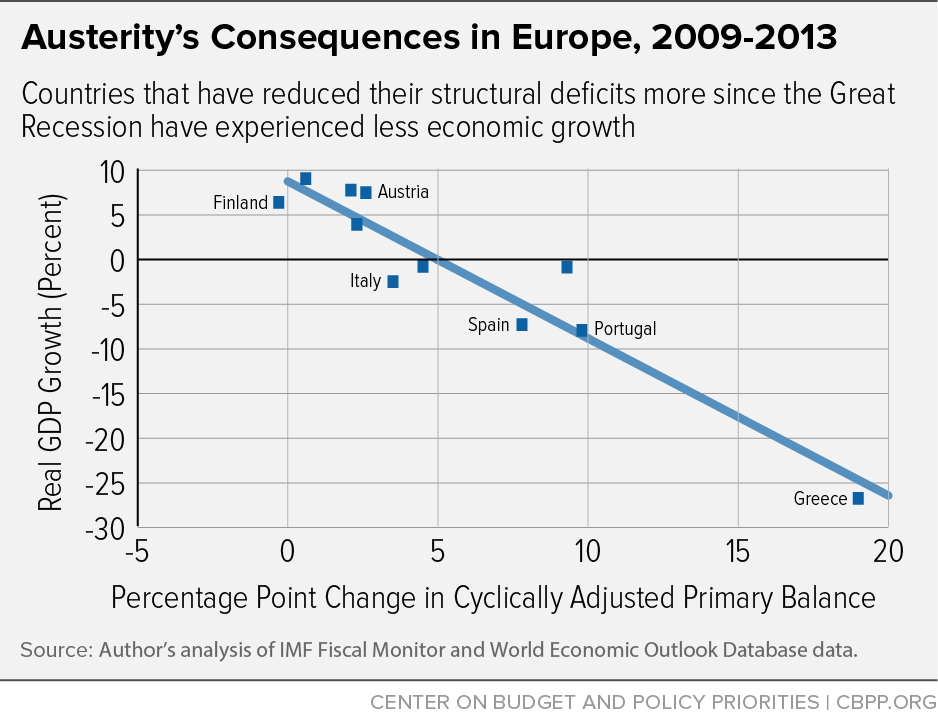

Examples of the damage done by premature fiscal contraction, aka austerity, can be seen both in Europe and in the United States. The figure below shows real GDP growth in Eurozone countries between 2009 and 2013 plotted against the percentage point change in the cyclically adjusted primary balance as a share of GDP.[4] Countries that tightened their fiscal stance while underlying growth was still weak saw less GDP growth than countries more willing to apply the shock absorber of temporary deficit spending.

As the Great Recession took hold, U.S. fiscal policy moved quickly into “shock absorber” mode, with both automatic and discretionary stimulus measures. But we, too, pivoted to austerity too soon, both with the premature sunsetting of a temporary paycheck booster (the “payroll tax holiday”) in 2013 and with spending cuts that year from sequestration. According to Goldman-Sachs, that pivot cost the U.S. economy 1.6 percent of lost GDP in 2013 — over a million jobs lost based on historical relationships and about three-quarters of a point added to unemployment — at a time when the U.S. economy was still trying to recover from the residual pull of the Great Recession. In 2014, when fiscal impulse turned neutral, unemployment fell more quickly and job growth accelerated.

But States and Families Have to Balance Their Budgets:

Why Shouldn’t the Feds?

Two arguments often proffered as to why the federal government should regularly balance its budget are: a) families have to balance their budgets and tighten their belts in hard times, and b) states have to balance their annual budgets.

These analogies fail for two reasons.

First, families and states don’t actually balance their budgets every year, nor should they. To do so would mean significant disinvestment in the future. Families frequently take out long-term loans to acquire key wealth-generating assets, like a home or college education. And while states have to balance their annual operating budgets, they can and do run capital budget deficits, as they incur potentially long-term debt to purchase and maintain highways, land, and buildings. As the National Council of State Legislatures puts it:

The common state practice is to consider that borrowing for capital expenditure does not violate the principle of maintaining a balanced budget. Borrowing for capital expenditure does not legally violate state balanced budget provisions, either because those provisions specify a way that general obligation debt may be issued, or because, in states that do not permit general obligation debt, judicial decisions have validated the issuance of other forms of debt.[5]

Summing across state and local governments, capital budgets reflect the issuance of $3 trillion in debt. So if states accounted for borrowing and spending the same way that the federal government does, many of them would also routinely run deficits.

Second and more important, the fact that states must balance their (operating) budgets and that families often must “tighten their belts” in downturns is not a reason for the federal government to do the same. To the contrary, if states and families are “tightening” (reducing spending), it is that much more essential for federal fiscal policy to counteract that dynamic by increasing spending to offset the fiscal drag from the states. And, of course, virtually all of the money the federal government spends goes to our residents and is spent here in the United States.

As an analogy, imagine the 50 states and Uncle Sam all in a boat that’s taking on water. Unless they bail, they’ll sink. But Sam’s the only one with a bucket. By dint of his essential ability to run budget deficits, Sam represents the states’ best hope for staying afloat during a recession. To enforce budget balancing in this situation is to take away Sam’s bucket, too.

Recent Republican Budgets: Unbalanced With High Potential Costs to the American People and Economy

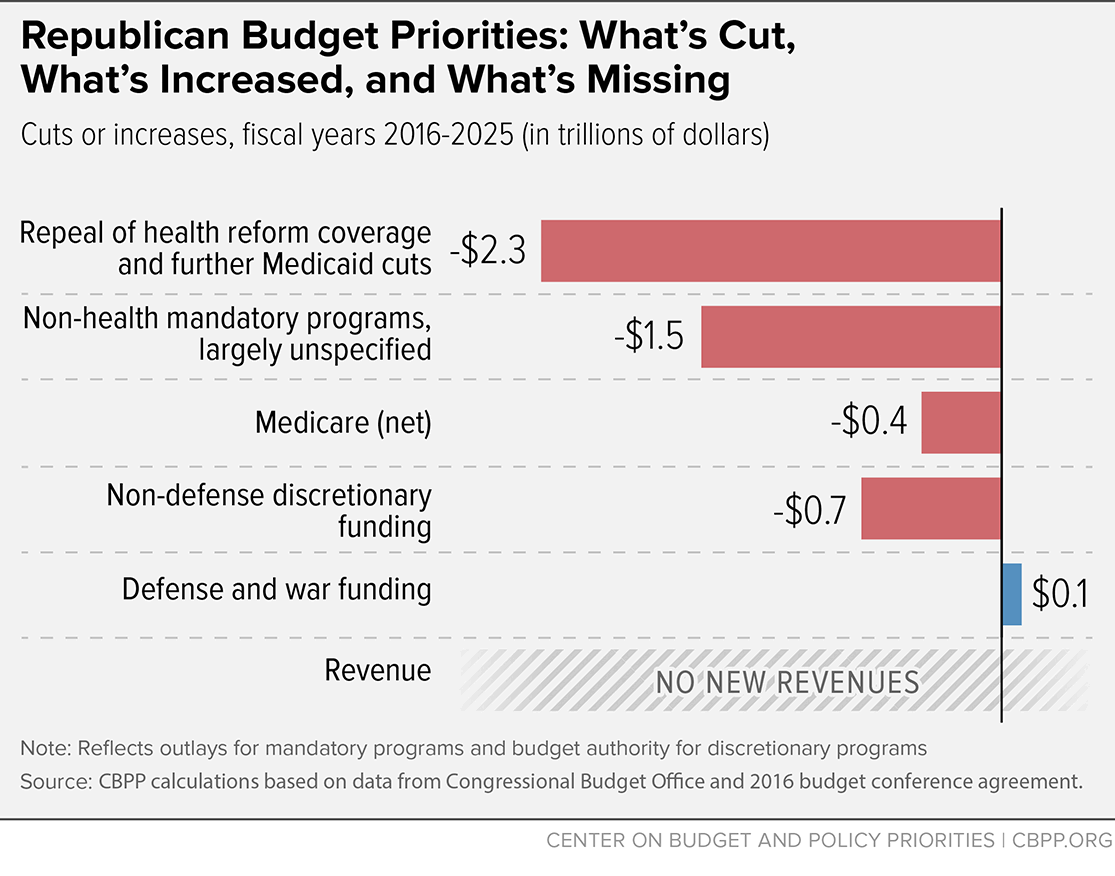

The aforementioned ideas on optimal fiscal policy raise numerous concerns regarding recent Republican budgets. For example, the recently adopted 2016 budget resolution violates many of the optimality principles articulated above. It lacks balance in that it cuts almost $5 trillion over the next decade from non-defense programs, “shrinking much of government to levels not seen in the modern era,” a CBPP analysis explains.[6] It raises no new revenues; it closes none of the wasteful, inefficient tax loopholes that partisans on both sides of the aisle have decried. Its cuts mostly come out of programs that serve families with low incomes. “If implemented, it would cause tens of millions of people to lose their health insurance or become underinsured, reduce basic food assistance for large numbers of low-income families and individuals, shrink support for millions of working families struggling to make ends meet, and make it harder for low- and modest-income students to afford college,” according to CBPP.

Austerity measures that hurt near-term growth. As this testimony has stressed, optimal fiscal policy does not involve fiscal consolidation while output gaps persist. Much as European austerity has weakened economies in the Eurozone, CBO estimates that the Republican budget resolution would initially slow growth: “Real GNP per person would be lower by as much as 0.6 percent under the specified paths than under the baseline from 2016 to 2018, CBO estimates, because reduced federal spending relative to current law would dampen overall demand for goods and services…”[7]

The budget agency believes the deficit and debt reduction proposed in the Republican budget in later years would lead to greater investment, capital stock, and labor supply relative to the baseline, which would, in turn, eventually lead to faster growth. However, as stressed below, various analysts have expressed legitimate skepticism about whether the resolution would actually achieve the balance it claims.

Skewed approach toward spending cuts. The figure below shows the $4.9 trillion cut in non-defense programs in the 2016 budget resolution (defense spending gets an increase). Notably, the budget raises no revenues; all of the savings are generated through spending cuts on non-defense programs.

Deep spending cuts. At least 63 percent of the $4.9 trillion in cuts come from low-income programs, including Medicaid (the proposed repeal of the Affordable Care Act would lead millions to lose coverage from the Medicaid expansion and millions more to lose affordable coverage from the exchanges), Pell Grants, and pro-work, anti-poverty tax credits for low-income working families.

Outside of Social Security, Medicare, and interest payments on the debt, spending in the budget resolution falls to about 7 percent of GDP in 2025, far below the long-term 12 percent average (such spending is currently about 11 percent of GDP). Such disinvestment is clearly incompatible with the optimal spending policy described above.

The Republican budget resolution also eliminates key funding for program integrity activities, which saves more money than it costs — between 2012 and 2014, for example, program integrity funding for Medicare and Medicaid saved $8 for every $1 spent. These cuts reverse previous bipartisan agreements to keep additional funding for program integrity outside the caps imposed by sequestration, an option that previous Congresses have used to fund program integrity. This plan eliminates all such funding.

Disinvestment in transportation infrastructure. A few weeks ago, a Washington Post article ran under this headline: “With 61,000 bridges needing repair, states await action on Capitol Hill.”[8]

At about the same time, a CBPP analysis prepared before House and Senate Republicans reconciled their separate budgets showed that the plans “cut highway construction and other transportation infrastructure funding over the next decade by 28 percent and 22 percent, respectively, below the cost of maintaining current funding levels.”[9] The initial House budget called for cutting mandatory transportation funding by almost 90 percent in 2016, from $54 billion to $6 billion.

The Republicans’ joint budget avoids this sharp drop in 2016 but cuts highway and mass transit funding by 40 percent over the next decade. Keep in mind that the federal gas tax that supports these productivity-enhancing investments has been stuck at 18.3 cents per gallon since 1993. This tax has not been adjusted to reflect inflation, the condition of the infrastructure it pays for, or the fact that today’s auto fleet gets much better mileage than that of 20 years ago.

Clearly, such budgeting is a classic violation of the optimality principles articulated above. Public infrastructure like roads and mass transit will not be amply provided by the private sector; its provision is a well-established role of government on behalf of the safety, wants, and needs of its citizens and productivity of its businesses. As the Post headline suggests, funding infrastructure is not a partisan issue; it’s a matter of public officials meeting the needs of states, both red and blue. Yet instead of stepping up and making these critical investments, the Republican resolution bases infrastructure spending not on the size of our needs but on the level that can be supported by the obviously insufficient inflow of gasoline tax revenue.

Likely inability to achieve balance. The resolution includes some notable inconsistencies, particularly regarding future revenue streams, that challenge its claim of achieving balance over the next decade. Most notably, the plan repeals the ACA but keeps the $1 trillion in revenues (over ten years) from taxes implemented to help fund health care reform. “Either the budget overstates revenues and understates deficits by about $1 trillion or it assumes offsetting tax increases that are never explained,” a CBPP analysis noted.[10]

More recent fiscal actions by House Republicans underscore my contention that their budget will not get to balance in ten years. For example, they recently voted to repeal the estate tax at a projected ten-year cost of about $270 billion, with no offsets. This tax currently only hits the wealthiest top 0.2 percent of estates, so not only is this cut fiscally reckless, it threatens to exacerbate our already high levels of wealth inequality, and would almost surely serve to worsen America’s high levels of economic immobility.[11]

Similarly, the House voted to permanently extend a number of tax breaks, mostly for businesses (the so-called “extenders”), at a cost of about $300 billion over ten years — again with no offsets.

Altogether, that’s close to $1.6 trillion less revenue than what’s in the current baseline and in the Republican budget resolution. Thus, even if this Congress were to succeed in making the full spate of ill-advised spending cuts discussed above, I see no path to balance given these large, unpaid-for tax cuts.

I should also note that the resolution employs a gimmick — one derided by this very committee just last year — to spend beyond the 2016 sequestration cap on defense. The resolution puts $96 billion into the Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) fund, which does not count against the sequestration cap and which is $38 billion more than what the Pentagon says it needs for overseas operations. The plan thus allows the Pentagon to channel these extra resources into its base budget. Last year, this committee, then chaired by Rep. Paul Ryan, aptly denounced this gimmick as “a backdoor loophole that undermines the integrity of the budget process.”

This gimmick also violates the principle of parity between defense and non-defense: just as the sequestration cuts were imposed equally to defense and non-defense programs, so too should sequestration relief be allocated equally. Underfunding non-defense discretionary (NDD) programs — which include education, job training, infrastructure, scientific and medical research, veterans’ health care, child care, and more — is of particular concern because they are precisely the type of investment-oriented programs under the rubric of optimal spending policy (that is, investments that the private sector will underprovide). About one-third of NDD programs help Americans with low and moderate incomes.

In fact, between 2017 and 2025, the resolution calls for cutting NDD almost $500 billion beyond the already unsustainable cuts imposed by sequestration, more than doubling the NDD sequestration cuts already in the pipeline. These scheduled cuts alone — i.e., the cuts already on the books, not counting those in the budget agreement — will drive NDD to its lowest share of the economy on record by 2017 (with data available back to 1962).

These proposed cuts are not only inconsistent with optimal spending policy. They push in exactly the wrong direction in an economy wherein market outcomes are increasingly unequal and the rungs of the opportunity ladder out of poverty are increasingly far apart.

Conclusion

Our fiscal debate has become dangerously distorted. Balancing the budget, even at great cost to the need for counter-cyclical policy or critical investments in public goods, has been elevated as a laudable goal — a sign of fiscal rectitude. Putting aside the fact that many making this argument are simultaneously engaging in reckless tax cuts with no offsets, balancing the budget without regard for the dynamics I’ve stressed throughout is not optimal fiscal policy.

Instead, budget policy needs to be flexible, to respond dynamically to the nation’s needs. That by no means implies ever-growing deficits and debt. To the contrary, in advocating CDSH as optimal fiscal policy, I am firmly on the record arguing that, as the economy hits a bona fide recovery and heads toward full resource utilization, budgets should move toward primary balance and into primary surplus so that the debt will grow more slowly than GDP. In fact, as I pointed out, the historical record shows many years of debt-to-GDP reduction when deficits were non-zero (but below primary balance).

However, I have also strongly advocated for the CD (“cyclical dove”) part of the optimal policy, citing historical evidence of the importance of economic shock absorbers in the form of temporary fiscal expansion amidst demand contractions. I’ve also shown that governments both here and (especially) abroad have forgotten this historical lesson, turning to austerity measures at great cost to the economic opportunities of their citizens.

Finally, part of optimal fiscal policy is recognizing the essential role of the public sector in providing investments, goods, and services that the private sector will sub-optimally provide. For policymakers to sacrifice such investments at the altar of budget balancing is not simply to abrogate their responsibility to the least advantaged among us. It is to consign millions to unnecessary suffering due to an inadequate understanding of fiscal rectitude.

End Notes

[1] Robert Greenstein and Joel Friedman, “Balancing the Budget in Ten Years and No New Revenue Are Flawed Budget Goals,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 13, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/balancing-the-budget-in-ten-years-and-no-new-revenue-are-flawed-budget-goals.

[2] Jared Bernstein, “The Reconnection Agenda: Reuniting Growth and Prosperity,” 2015, Chapter 4, http://jaredbernsteinblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/The-Reconnection-Agenda_Jared-Bernstein.pdf.

[3] Why “increasingly important?” Some economists believe that interest rates will remain low for the foreseeable future. If so, when we hit the next recession, the likelihood that the Federal Reserve will again face the “zero lower bound” on the federal funds rate is heightened, implying a more important role for fiscal policy.

[4] Since we expect deficits to go up to some degree in recessions (e.g., due to lower revenue flows), it is important to measure the extent of austerity against a cyclically adjusted budget deficit. This approach will identify countries that undertook austerity measures yet still ran cyclical deficits.

[5] “NCSL Fiscal Brief: State Balanced Budget Provisions,” October 2010, http://www.ncsl.org/documents/fiscal/StateBalancedBudgetProvisions2010.pdf.

[6] See Joel Friedman, Richard Kogan, and Isaac Shapiro, “The Congressional 2016 Budget Plan: An Alarming Vision,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 8, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/the-congressional-2016-budget-plan-an-alarming-vision.

[7] “Budgetary and Economic Outcomes Under Paths for Federal Revenues and Noninterest Spending Specified in the Conference Report on the 2016 Budget Resolution,” Congressional Budget Office, April 2015, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/50115-ConferenceReport.pdf.

[8] Ashley Halsey III, “With 61,000 bridges needing repair, states await action on Capitol Hill,” Washington Post, April 1, 2015, http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/trafficandcommuting/with-61000-bridges-needing-repair-states-await-action-on-capitol-hill/2015/04/01/3bf842ce-d860-11e4-8103-fa84725dbf9d_story.html.

[9] David Reich, “House, Senate Budgets Have Big Cuts in Transportation Infrastructure,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 27, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/house-senate-budgets-have-big-cuts-in-transportation-infrastructure.

[10] Robert Greenstein and Richard Kogan, “Ten Serious Flaws in the Congressional Budget Plan,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated June 8, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/ten-serious-flaws-in-the-congressional-budget-plan.

[11] See “Policy Options for Improving Economic Opportunity and Mobility,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Manhattan Institute for Policy Research,” June 2015, http://pgpf.org/sites/default/files/grant_cbpp_manhattaninst_economic_mobility.pdf.

More from the Authors