- Home

- Income Security

- Temporary Assistance For Needy Families ...

Chart Book: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) at 26

Twenty-six years ago, Congress passed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), which created the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program as the nation’s primary source of cash assistance to help families with children work toward achieving their personal and family goals when they fall on hard times or have very low incomes. TANF replaced Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), a program that had been in existence since 1935. Since TANF’s creation, the accessibility and adequacy of cash assistance has fallen dramatically. In some states, primarily in the South and where Black children are likelier to live, TANF cash assistance has all but disappeared.

TANF provides a vital support to families with the lowest incomes: cash assistance. Other anti-poverty programs, such as SNAP and refundable tax credits, have grown significantly and have had a tremendous impact on reducing hardship, especially for Black and Latino families and individuals. Yet families with little or no cash income still need monthly cash assistance to be more economically secure.

Part I: TANF Cash Assistance Could Reach Millions More Families in Need

Part II: Higher TANF Benefit Levels Needed to Help Families Afford Their Basic Needs

Part III: States Should Invest More TANF Dollars in Cash Assistance, Supporting Work

Part IV: TANF Promised “Work, not Welfare” but Left Many Families with Neither

Part I: TANF Cash Assistance Could Reach Millions More Families in Need

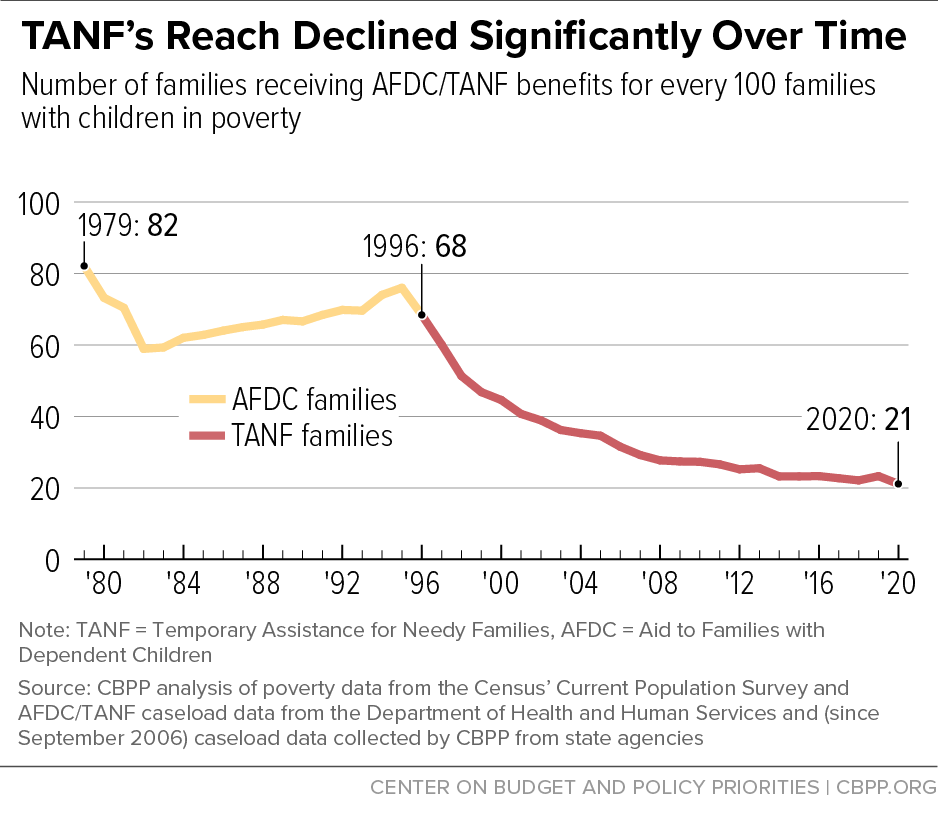

The most consequential change in TANF over the last 26 years is the decline in the number of families receiving cash assistance. During this period, the national TANF average monthly caseload has fallen dramatically even as poverty and deep poverty (incomes below half of the poverty line) remained widespread. In 2020, 5 million families with children were living in poverty, the first increase in poverty in five years. Widespread hardship due to the COVID-19 pandemic and related economic conditions have created instability for millions of families with children, some of whom have turned to TANF and other public programs for relief. And yet, for every 100 families in poverty, only 21 received cash assistance from TANF, down from 68 families when TANF was enacted in 1996. This “TANF-to-poverty ratio” (TPR) is the lowest in the program’s history.

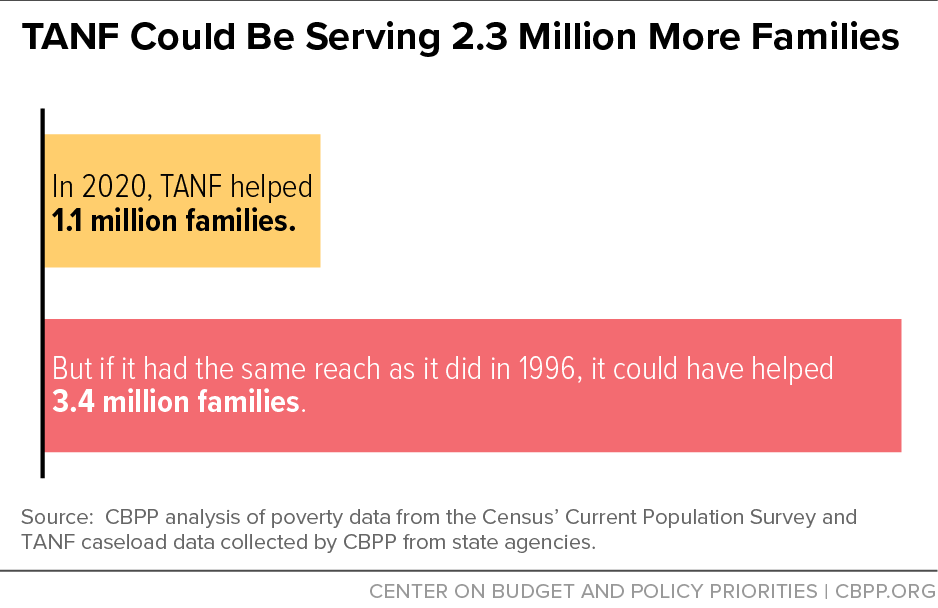

If TANF had the same reach now as AFDC did in 1996, the impacts would be substantial. The program would have reached 3.4 million families living in poverty in 2020, 2.3 million more families than TANF actually reached.

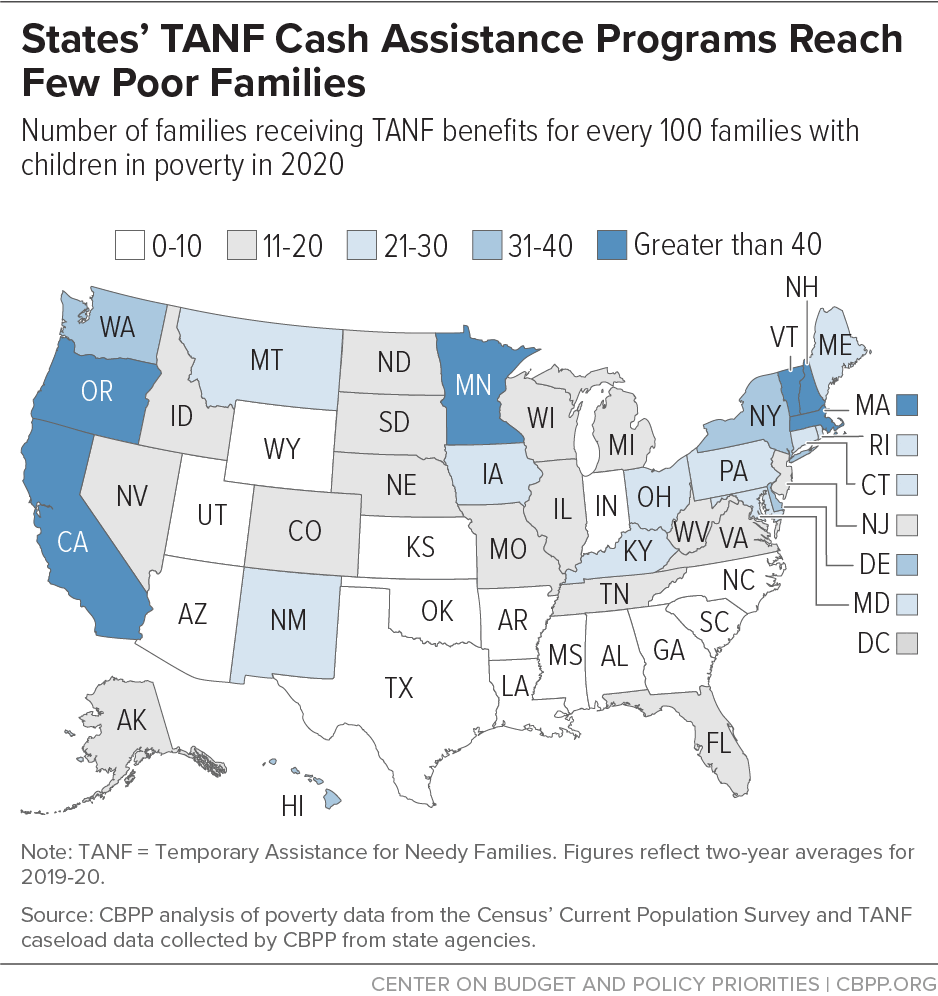

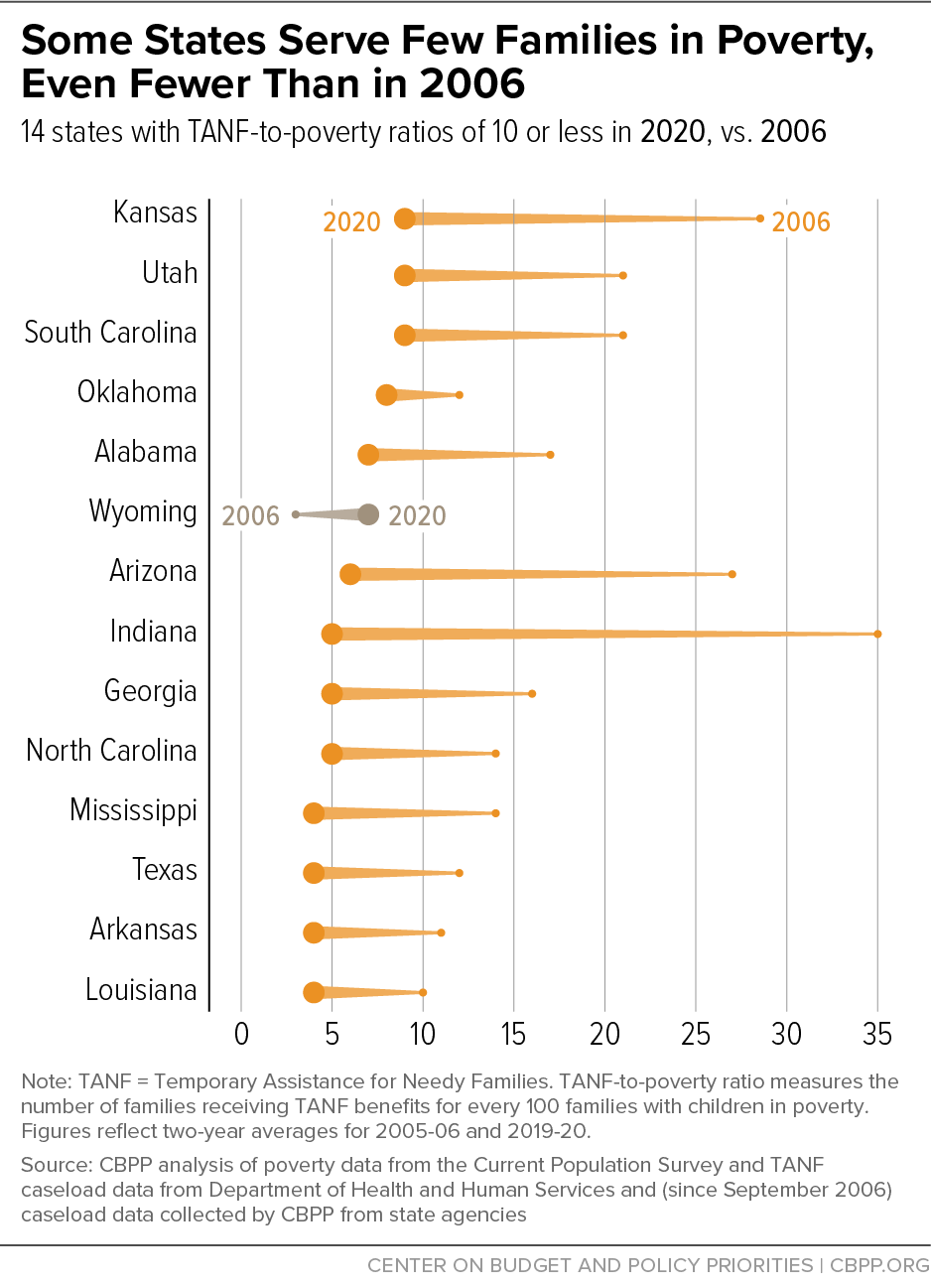

There is also extreme and growing variation in state-level TPRs. In 2020, the TPR ranged from 71 in California and Vermont to 4 in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. These data show that access to TANF largely depends on where families live. The geographic disparities reflect — and can widen — racial inequities in TANF: Black children are likelier, and Latino children are somewhat more likely, than white children to live in states with the lowest TPRs. Forty-one percent of the nation’s Black children live in states with TPRs of 10 or less, compared to 34 percent of Latino children and only 29 percent of white children.

This trend of more states having TPRs of 10 or less, a number that has increased dramatically in the last 16 years, is especially troubling. In 2020, 14 states had TPRs of 10 or less, compared to just three in 2006 and zero in 1996. Significant policy or administrative changes that made it harder for families to receive benefits account for these sizable declines.

Part II: Higher TANF Benefit Levels Needed to Help Families Afford Their Basic Needs

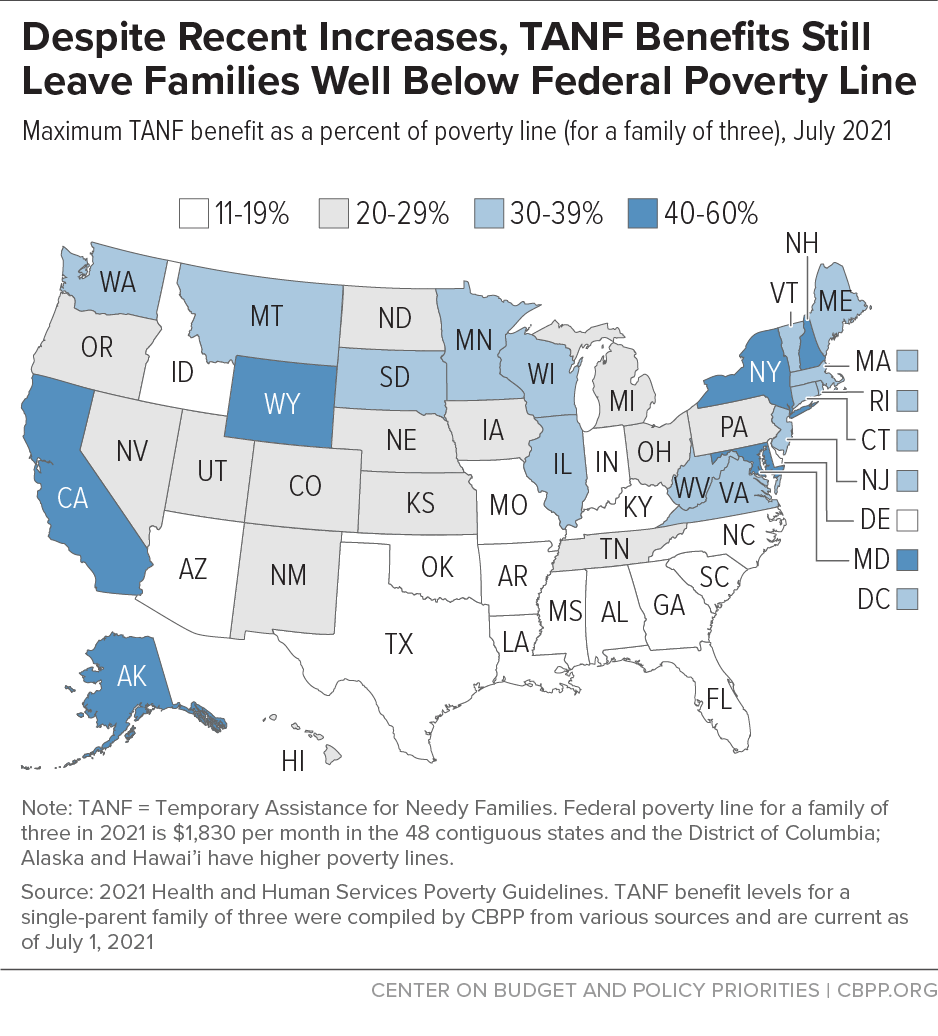

Not only do fewer families in need receive TANF cash benefits, but benefit levels for those who do are inadequate. Despite recent increases, in 2021 the maximum TANF benefit for a family of three in every state was at or below 60 percent of the poverty line, and benefits fell below 20 percent in 16 states.

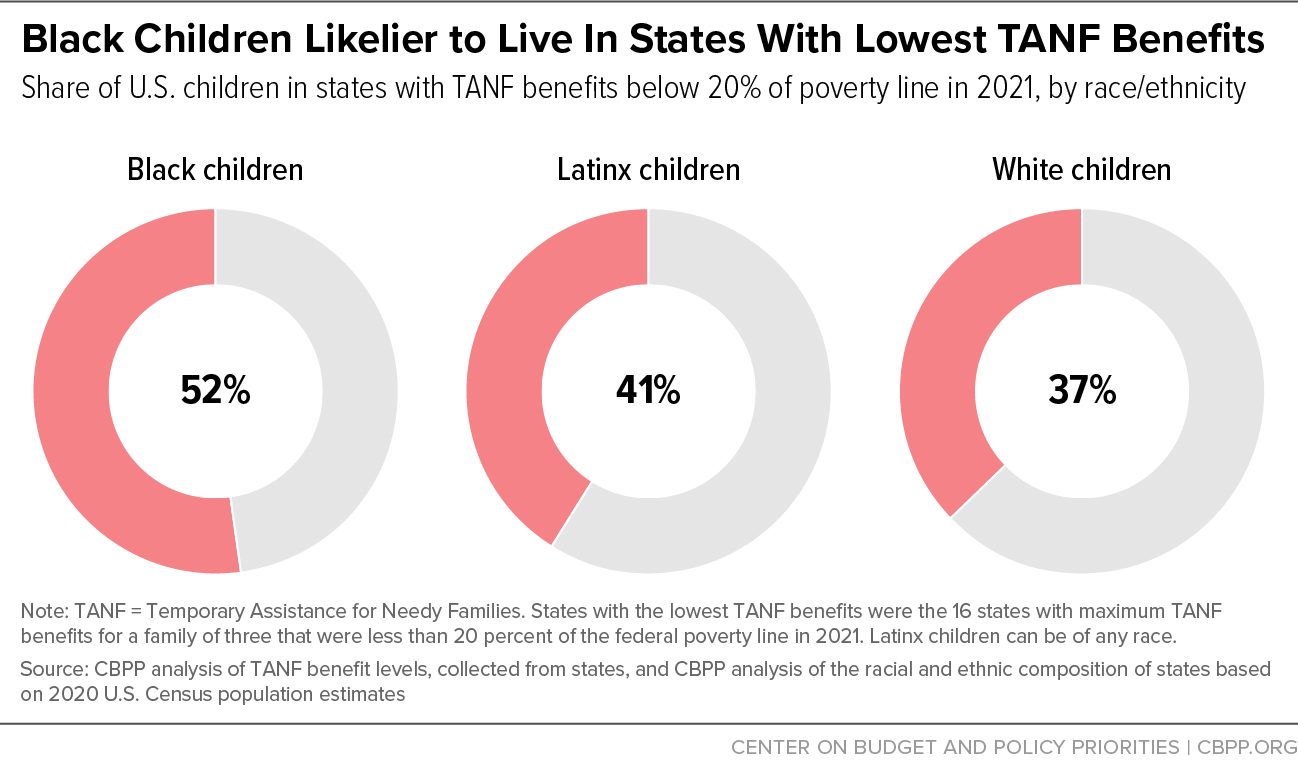

The erosion of TANF benefits, as with that of program access, has been more severe in states where Black children are likelier to live: a majority (52 percent) of Black children in the country live in a state with benefits at or below 20 percent of the poverty line, compared to 41 percent of Latinx children and 37 percent of white children.

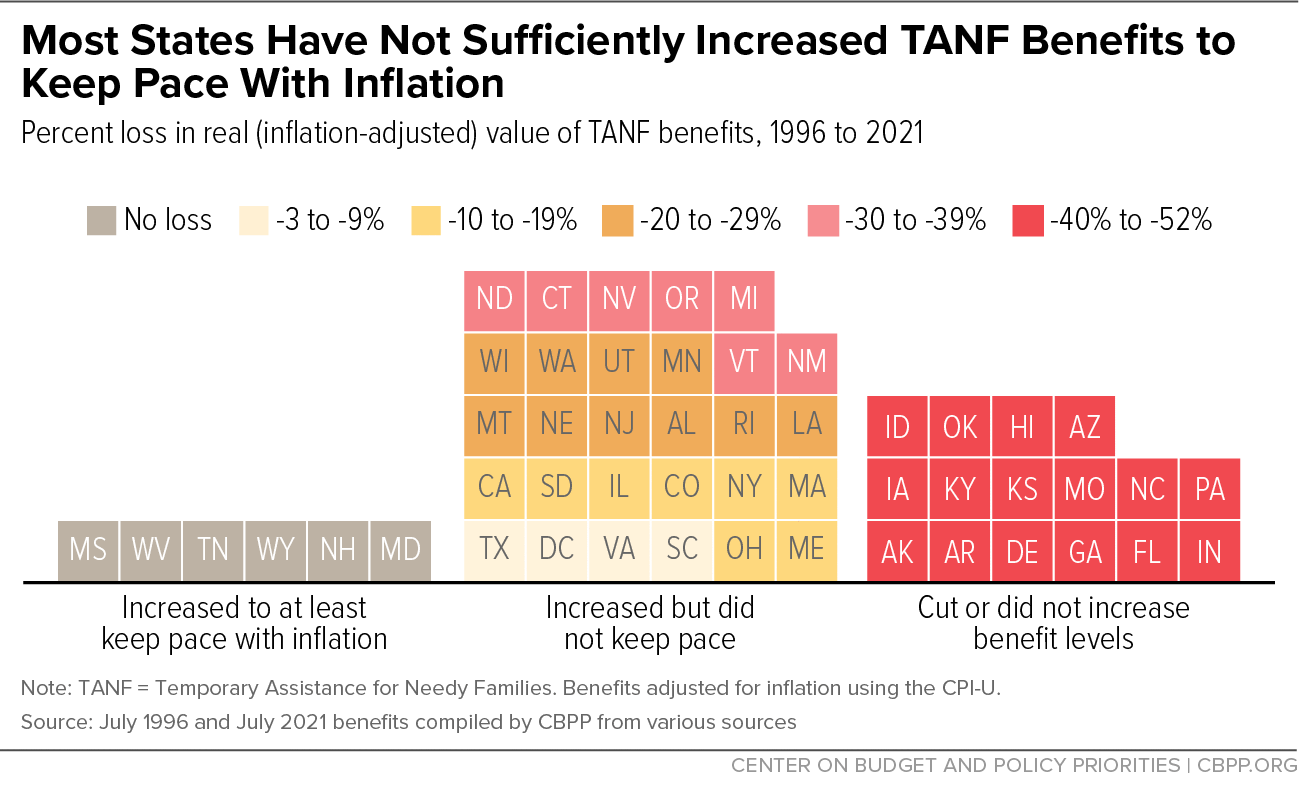

TANF benefit levels were not adequate in most states at the start of the program, and most states have allowed their benefits to erode even further. In all but six states, the real (inflation-adjusted) value of TANF cash benefits has fallen since 1996. At the other extreme, one-third of states either did not increase or cut benefit levels since 1996 and have lost 41 percent or more of their value to inflation. In the remaining 29 states, benefit increases were not sufficient to keep pace with inflation, leading to an average value loss of 21 percent. The recent spike in inflation means that TANF benefits are doing even less to help low-income families afford the rising costs of basic needs.

The decline in benefits since 1996 follows a quarter-century of major declines in the real value of benefits provided through AFDC. Between 1970 and 1996, AFDC benefits fell by more than 40 percent in two-thirds of the states, after adjusting for inflation, leading to the gradual weakening of AFDC as an anti-poverty program. Even 50 years ago, regional disparities were evident: Southern states — as they do today — provided far lower benefits than the national median.

Cash Assistance Historically Weak in Southern States, Now Weak in Most States

Maximum AFDC/TANF benefits by state in nominal dollars and as share of federal poverty line, 1970-2021

Note: Policymakers replaced AFDC with TANF in 1996. Calculations are based on the maximum AFDC/TANF benefit available to a family of three.

CBPP analysis based on benefits data compiled from tables 5.5 and 5.9 in Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), "Aid to Families with Dependent Children: The Baseline," 1998 (1970-1990) and Zane and Reyes, "States Must Continue Recent Momentum to Further Improve TANF Benefit Levels," CBPP, 2021 (1996-2021). 1990 benefit level for Pennsylvania was changed from what is reported by HHS to better align with 1996-2021 benefit levels with data from the state TANF manual.

Part III: States Should Invest More TANF Dollars in Cash Assistance, Supporting Work

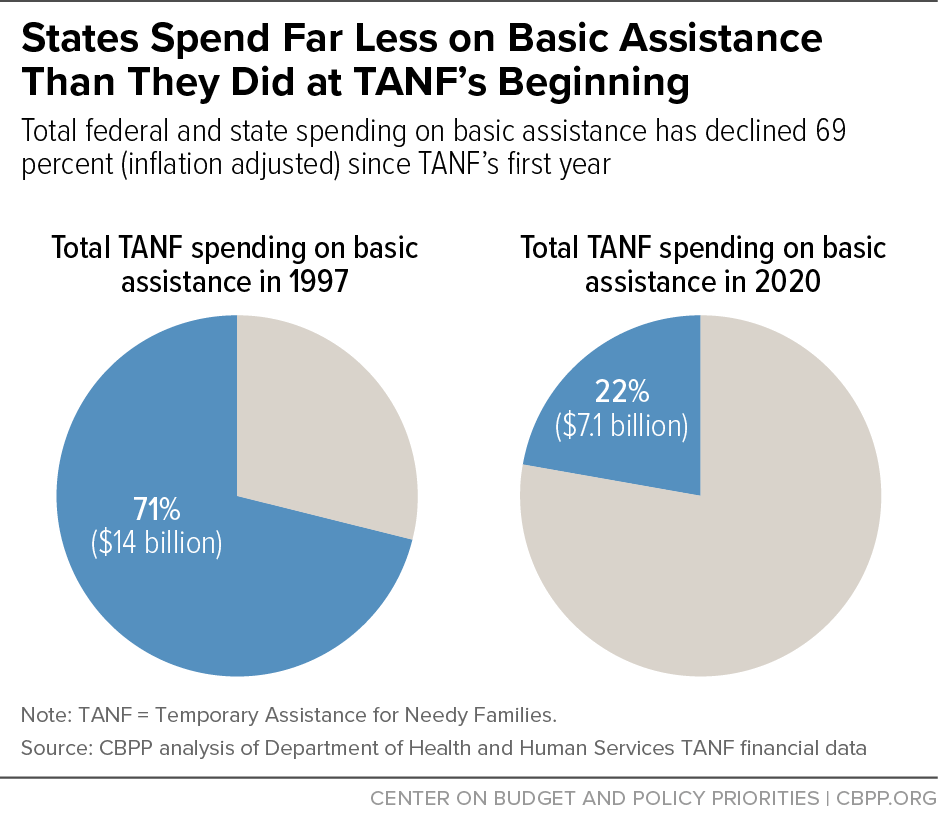

The TANF block grant fundamentally altered both the structure and allowable uses of federal and state dollars previously spent on AFDC and related programs. Under TANF, the federal government gives states a fixed block grant totaling $16.5 billion each year. This amount has not increased since 1996 and when accounting for inflation, is now worth 40 percent less than when TANF was created. States are also required to sustain a certain level of state maintenance of effort (MOE) spending (totaling $10 to $11 billion per year), based on a state’s level of spending for AFDC and related programs prior to its conversion to TANF in 1996.

Before TANF’s creation, virtually all AFDC funding, federal and state, went to providing cash benefits (i.e., basic assistance) to families with children. As TANF caseloads declined dramatically, states diverted funds elsewhere that had previously gone to families with very low incomes in the form of basic assistance. States used the flexibility the block grant gave them to redirect those funds, and spending on basic assistance has plummeted.

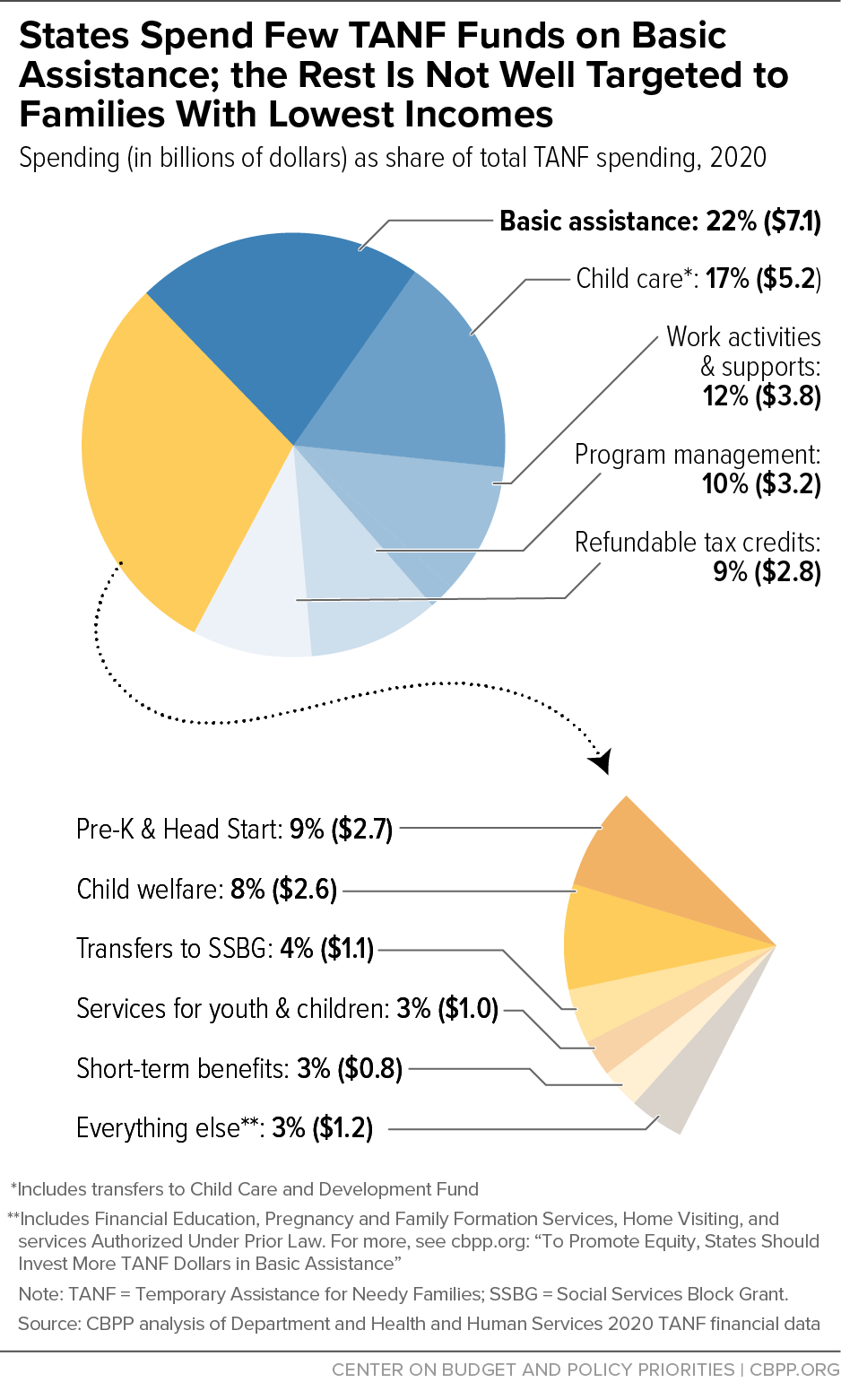

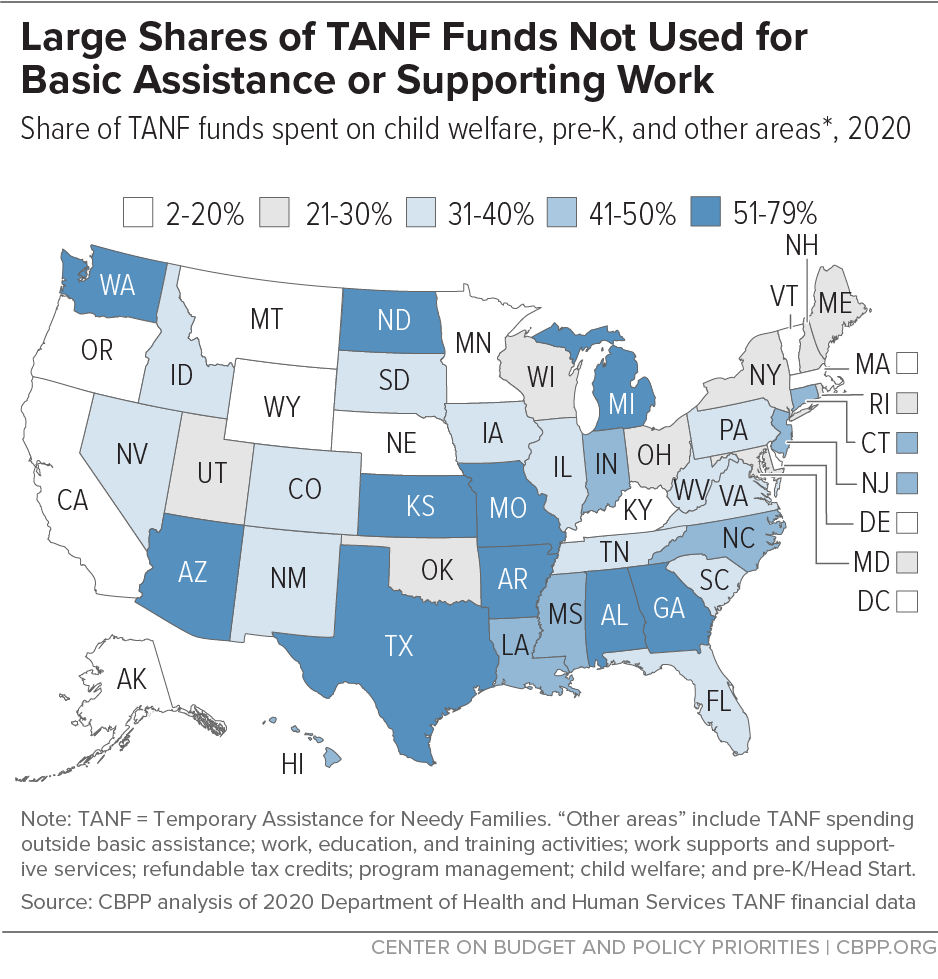

A key feature of the TANF block grant is that states can use their federal TANF dollars and state MOE funds to support a range of activities related to promoting the four purposes of TANF specified in federal law, which are quite broad. Because of this, states have been able to shift funds that were previously used to provide cash assistance toward many other uses. Unlike basic assistance, spending on these other categories is often not targeted to families with the lowest incomes. For instance, the majority of spending on work activities in several states is spending on college scholarship programs made available to families with incomes well above the poverty line — not preparing or connecting TANF participants to work opportunities.

Some TANF funds have been redirected from cash assistance to programs, like child care, that support and encourage employment among low-income families. However, a significant portion (and in some states the majority) of TANF funds are used neither to meet families’ ongoing basic needs nor to support work. While spending on areas such as pre-K and child welfare are important investments, states should use funding sources other than TANF for them.

Part IV: TANF Promised “Work, not Welfare” but Left Many Families With Neither

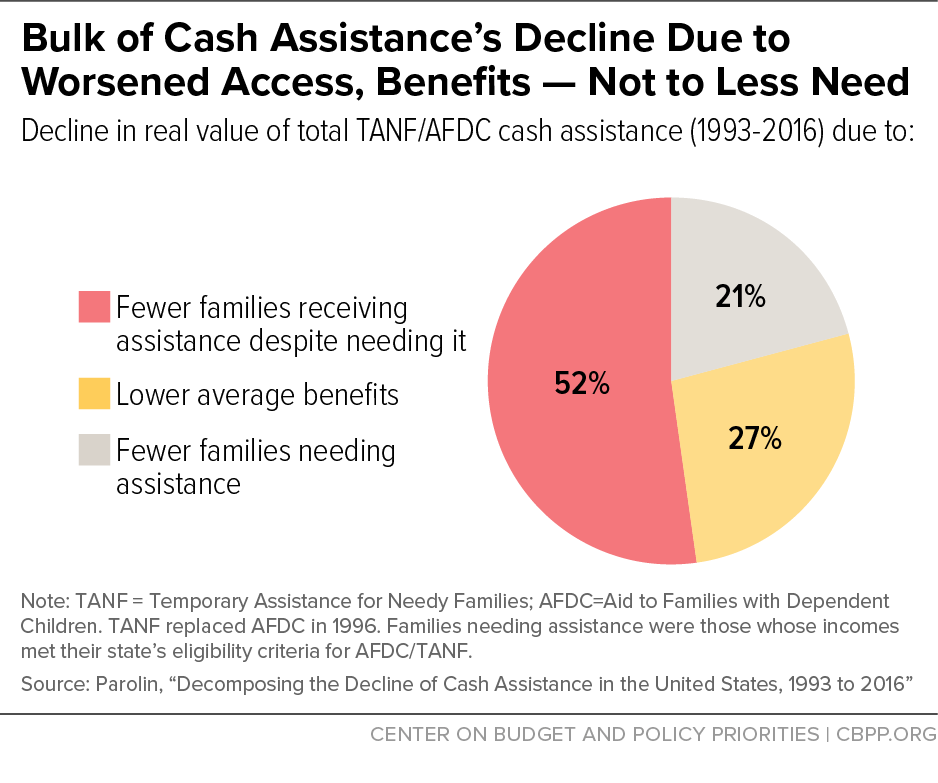

To explain the decline of TANF cash assistance, those who deem TANF a success point to demographic changes (e.g., increased employment among single mothers and a decline in single motherhood) that they claim has led to a lesser need for cash assistance. Those who deem it a failure point to the decline in the number of families in need receiving assistance and the value of cash benefits families receive.

Recent research shows that claims of TANF’s success are vastly overstated. The real value of the total amount value of TANF cash assistance provided annually to families under TANF and its predecessor fell 78 percent between 1993 and 2016, according to a recent study. Over half of that decline was due to fewer families participating in the program despite needing it, and over a quarter was due to lower average benefit levels. Just one-fifth of the decrease was due to reduced need, which includes any increase in employment that might have occurred.

The story of TANF’s failure is a story of the consequences of racist, anti-Black policies for all families. Steep barriers, including discrimination in the labor market and in government policies, have led to disproportionate levels of poverty among Black mothers. Instead of addressing these barriers, policymakers attributed Black mothers’ circumstances to false and harmful stereotypes such as the “welfare queen,” which painted low-income Black women as unwilling to work and targeted them for behavioral requirements and reproductive control. These stereotypes were also used to justify two key policy changes — work requirements and time limits — in TANF that, along with the block grant structure, have contributed to its weakening (and near demise in some states).

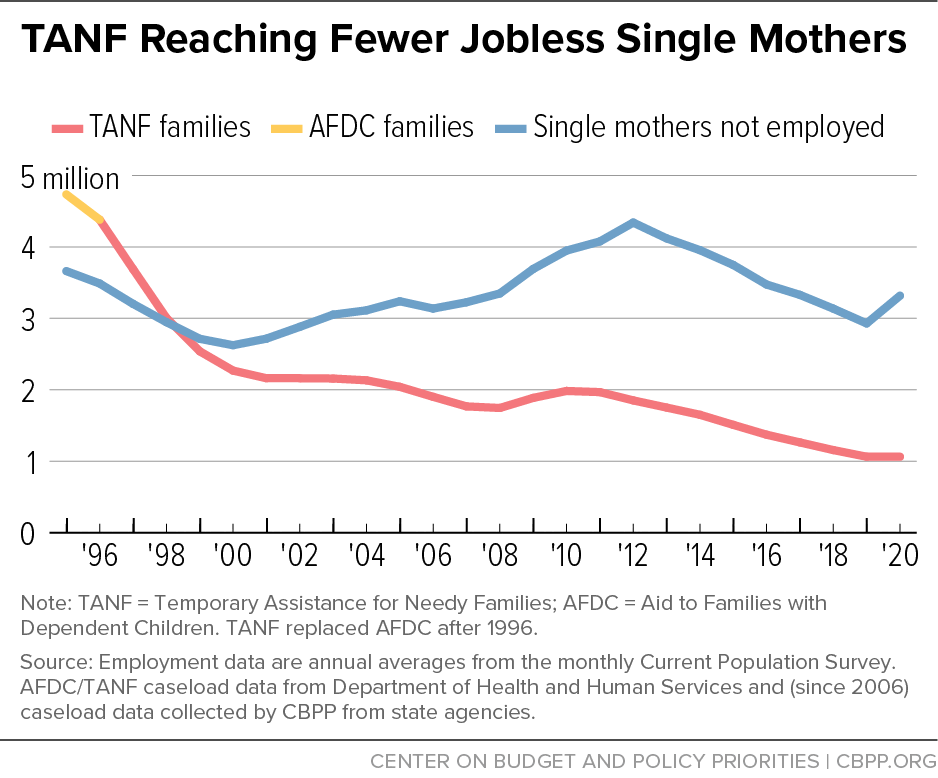

In large part because of sanctions that take away benefits for not meeting work requirements, TANF today reaches few non-working families and leaves many families with children with no regular cash income. In 2020, 3.3 million single mothers did not work for pay, yet only 1.1 million families received TANF at some point during that same year. This suggests that many non-working single mothers may not have access to the employment opportunities and work supports that TANF is supposed to provide. In 1996, in contrast, the number of families receiving AFDC that year exceeded the number of non-working single mothers. The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on labor market participation was most acutely felt by single mothers; yet, in 2020, caseloads in most states did not rise with the greatly elevated levels of hardship families faced during the pandemic. (See Figure 2 in our annual report on TANF access and caseloads.)

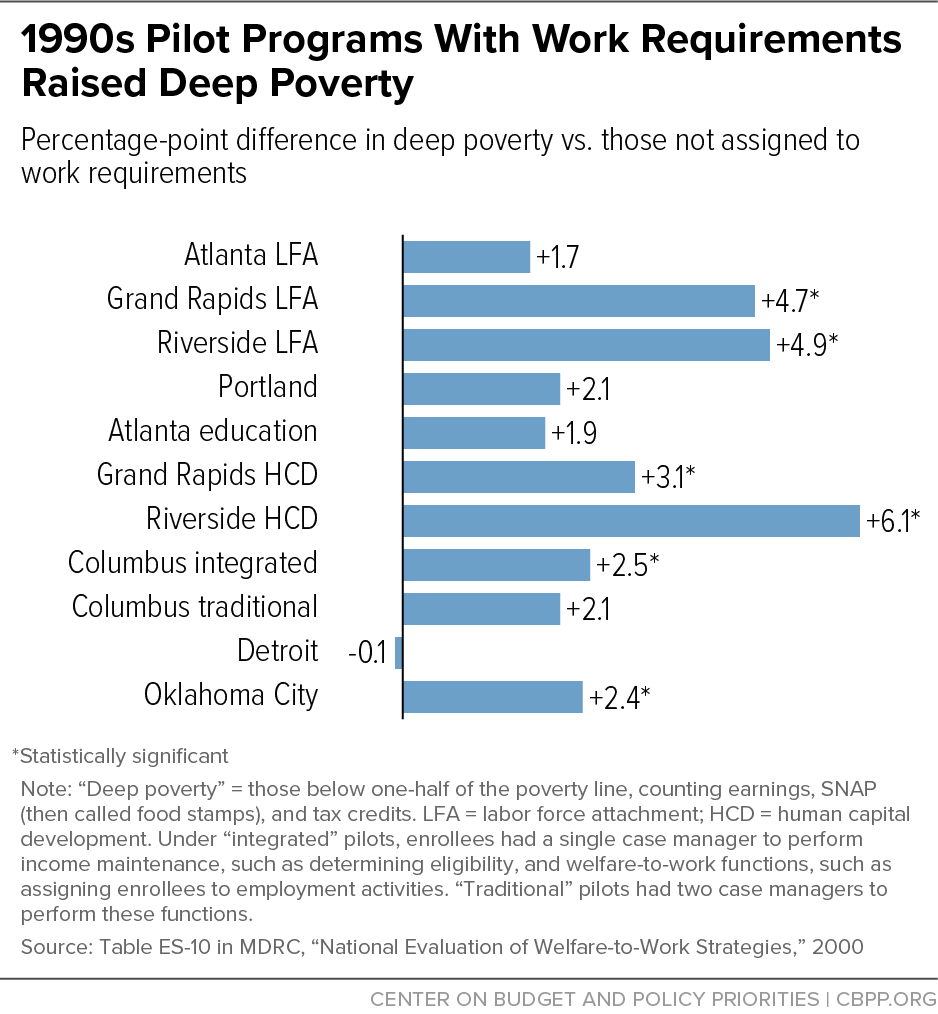

Contrary to claims that work requirements help families reach economic independence, large randomized controlled trials, the gold standard of research, in the 1990s offered scientific evidence that AFDC/TANF work requirements caused a rise in deep poverty for recipient families. The study examined 11 pilot programs — local forerunners of TANF’s work requirements — and found that while most of them slightly improved short-term employment and overall poverty rates, the deep poverty rates rose by a statistically significant amount in six of the 11 programs and didn’t fall significantly as many families had their benefits reduced or taken away.

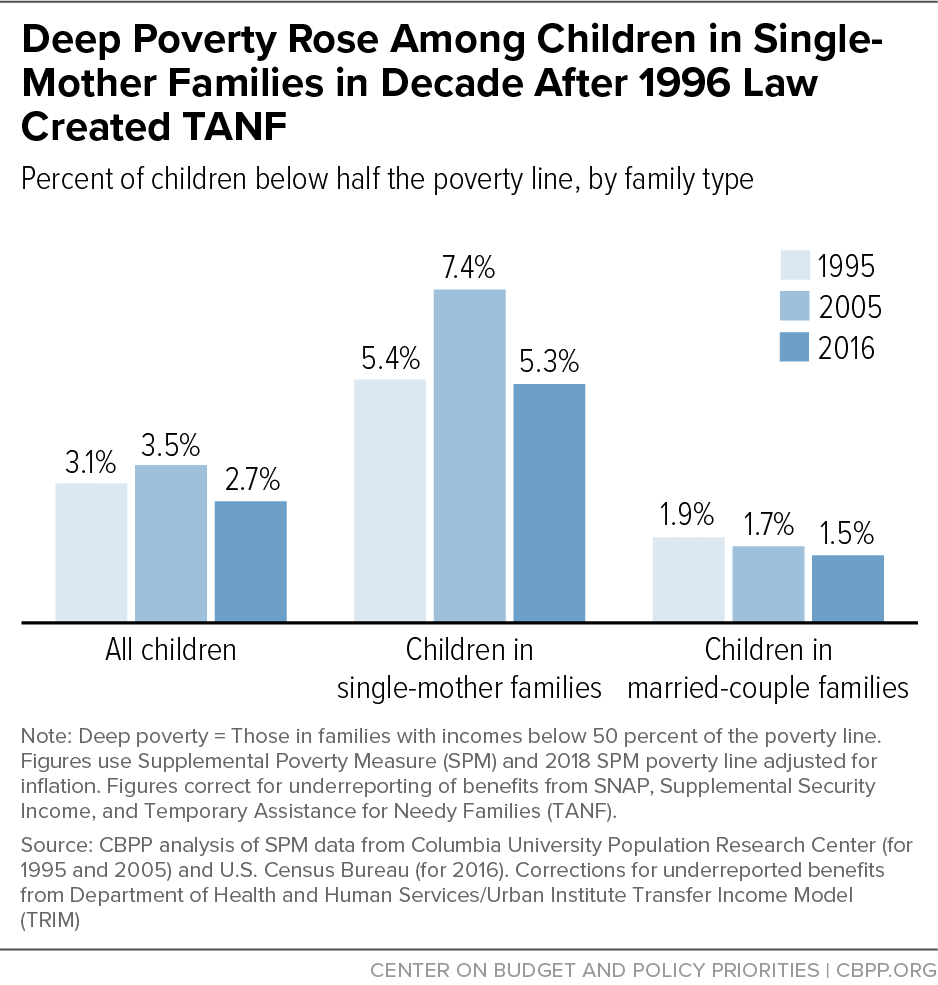

During TANF’s first decade, work requirements and time limits contributed to a rise in deep poverty among children as millions of families lost cash assistance. Between 1995 and 2005, deep poverty rose from 5.4 percent to 7.4 percent among children in single-mother families, whom the replacement of AFDC with TANF most affected. The period between 1995 to 2005 is most suitable for examining the effects of the 1996 law that created TANF because it extends from the year before the law’s enactment until ten years later, when the law’s major changes had mostly played out, and before significant additional changes in other low-income policies began blunting its negative impact on deep poverty.

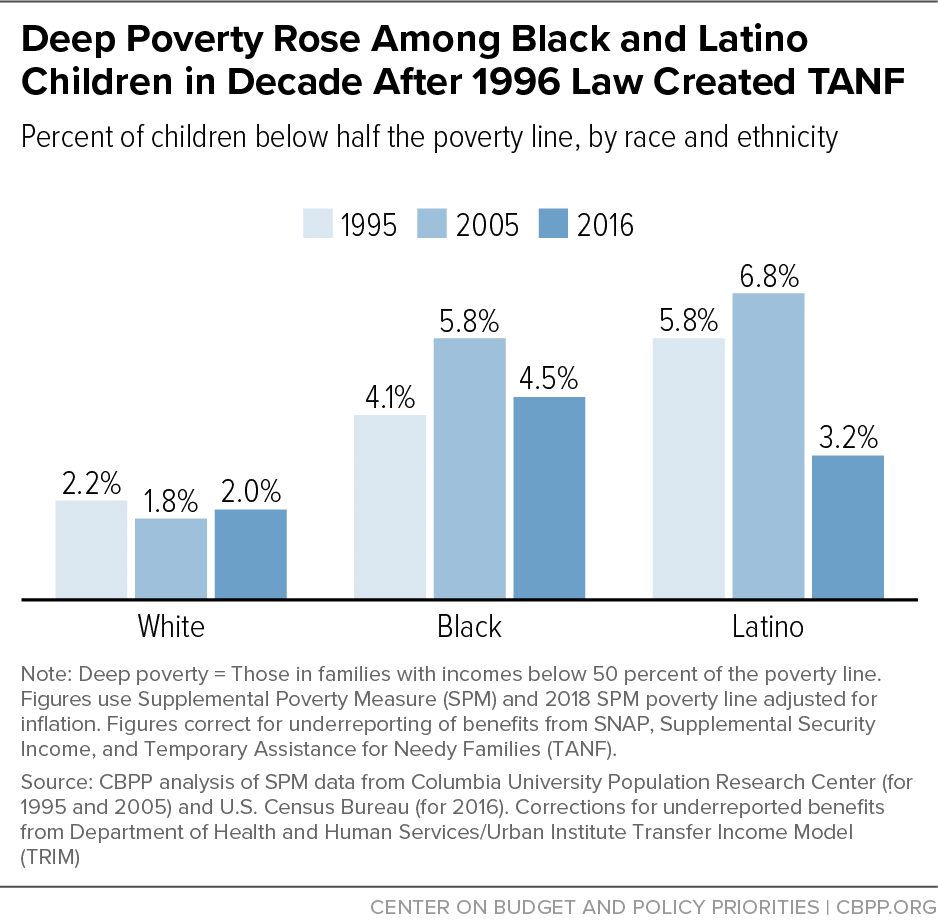

When looking at changes in deep poverty among children in TANF’s first decade, racial disparities are also evident. Black and Latino children experienced higher levels of deep poverty than white children during that same decade. Black families were at particular risk of deep poverty as TANF weakened, in part because of structural racism in the labor market and government policies. Studies have also shown that, all else being equal, states with higher concentrations of Black residents have more punitive and less generous TANF policies, and those states tend to spend less on basic cash assistance. Black and other TANF participants of color are also significantly more likely to be sanctioned than white families. For Latino children, the 1996 law’s reduction in access to cash and other government assistance for immigrants who recently arrived or who lack documented status also had a major effect on deep poverty. More recently, deep poverty rates receded for Black and Latino children due to the strengthening of other economic security programs and an improving economy, but racial disparities remain high.

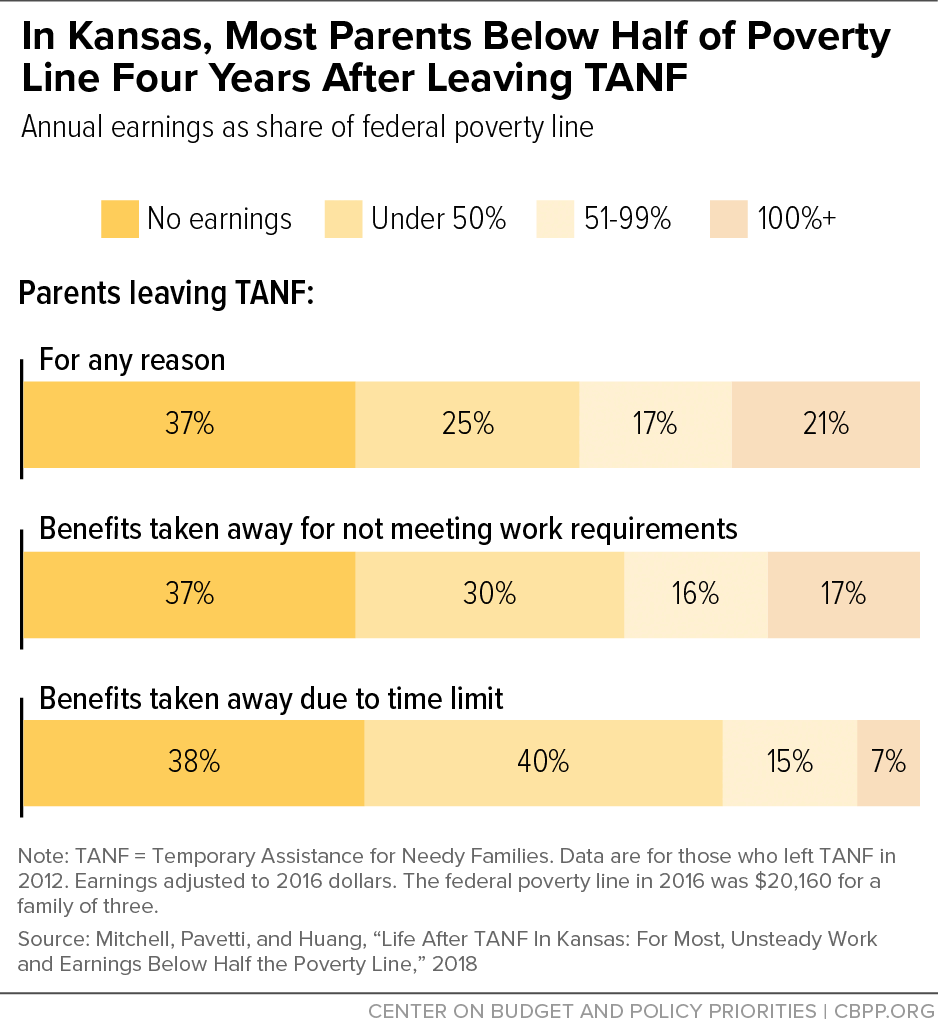

While employment that pays sufficient wages and provides regular hours can be a path out of poverty and toward financial stability, most TANF participants are not on that path, a recent look at employment outcomes of parents who left TANF in nine states found. Most parents worked before and after leaving TANF, but in unstable jobs where they often did not earn enough to escape deep poverty. In Kansas, 7 in 10 parents worked in the year after they left TANF, but only half as many earned wages that kept them above deep poverty. Additionally, most Kansas leavers had no or very low earnings four years later. Parents who left TANF because their benefits were taken away due to work requirements or time limits fared even worse. These poor employment outcomes are partially driven by underfunded work programs that rely on racist policies that seek to get parents into jobs as quickly as possible, without regard to job quality or fit, and perpetuate occupational segregation that keeps women — especially Black women — in low-paid, unstable jobs that lead many to TANF in the first place. Fortunately, states have the flexibility to move their work programs in an antiracist direction that honors parents’ choices and supports them as they pursue work or education that can lead to long-term stability.