The 2017 Trump Tax Law Was Skewed to the Rich, Expensive, and Failed to Deliver on Its Promises

A 2025 Course Correction Is Needed

End Notes

[1] Tax Policy Center (TPC), “T17-0314 - Conference Agreement: The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act; Baseline: Current Law; Distribution of Federal Tax Changes by Expanded Cash Income Percentile, 2025,” December 18, 2017, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/conference-agreement-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-dec-2017/t17-0314-conference-agreement.

[2] Ibid. This includes the effects of all the law’s provisions in 2025, including its permanent provisions and those that expire after 2025.

[3] Congressional Budget Office (CBO), “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018 to 2028,” April 9, 2018, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651.

[4] CBO, “Budgetary Outcomes Under Alternative Assumptions About Spending and Revenues,” May 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-05/59154-Budgetary-Outcomes.pdf.

[5] Council of Economic Advisers, “Corporate Tax Reform and Wages: Theory and Evidence,” October 2017, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/documents/Tax%20Reform%20and%20Wages.pdf.

[6] Patrick J. Kennedy et al., “The Efficiency-Equity Tradeoff of the Corporate Income Tax: Evidence from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” November 14, 2023, https://patrick-kennedy.github.io/files/TCJA_KDLM_2023.pdf. The $114,000 threshold for the 90th percentile of the within-firm earnings distribution appears in an earlier version of the paper, dated December 9, 2022 (Table 5, Panel A).

[7] Lucas Goodman et al., “How Do Business Owners Respond to a Tax Cut? Examining the 199A Deduction for Pass-through Firms,” NBER Working Paper 28680, January 2024, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28680/w28680.pdf. See also Chuck Marr and Samantha Jacoby, “The Pass-Through Deduction Is Tilted Heavily to the Wealthy, Is Costly, and Should Expire as Scheduled,” CBPP, June 8, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/the-pass-through-deduction-is-tilted-heavily-to-the-wealthy-is-costly-and.

[8] An analysis of the Bush tax cuts by Brookings Institution economist William Gale and Dartmouth professor Andrew Samwick, former chief economist on George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers, found that “there is, in short, no first-order evidence in the aggregate data that these tax cuts generated growth.” William Gale and Andrew Samwick, “Effects of Income Tax Changes on Economic Growth,” Brookings Institution, February 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/09_Effects_Income_Tax_Changes_Economic_Growth_Gale_Samwick_.pdf.

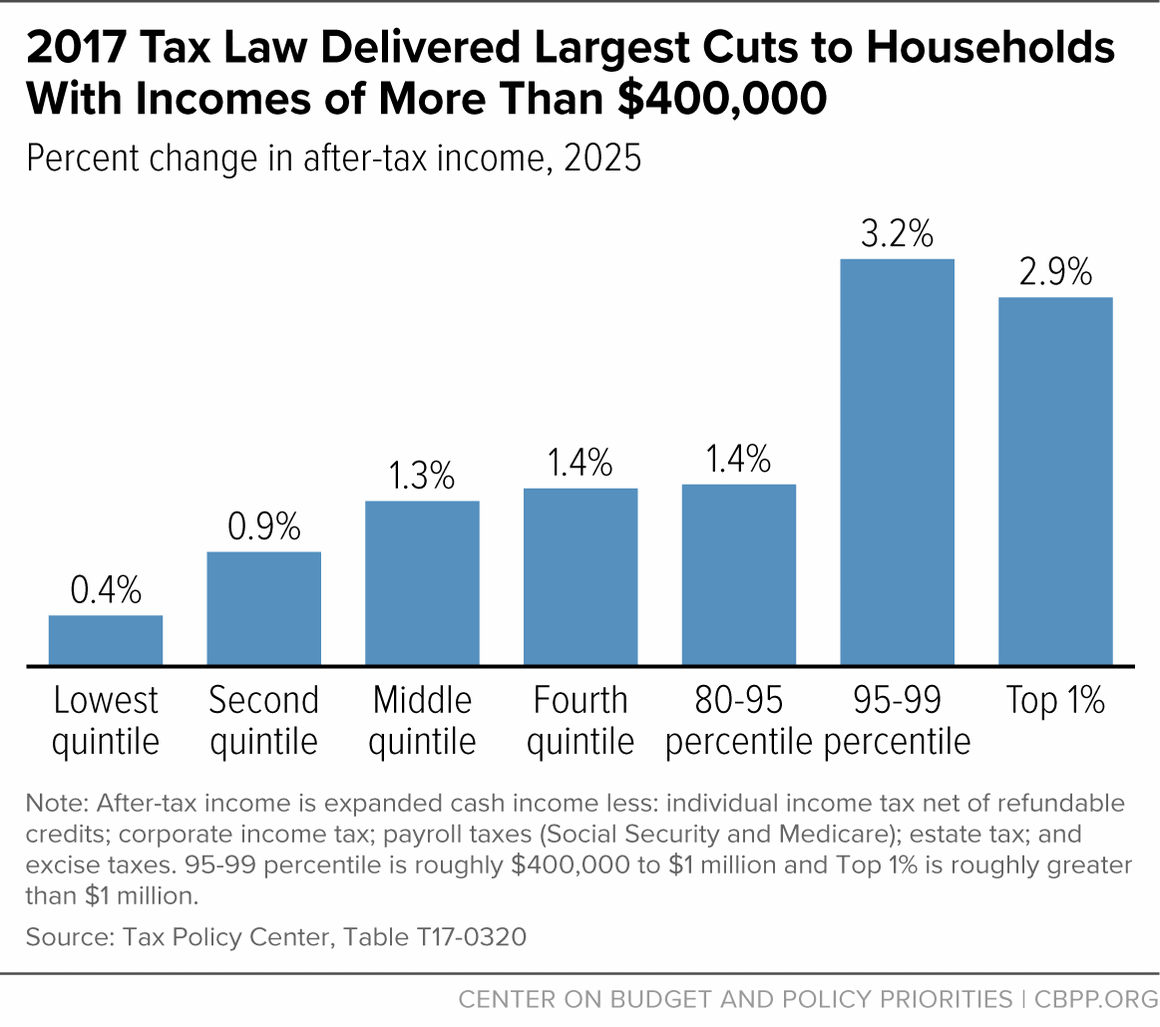

[9] TPC estimated that in 2010, the year the Bush tax cuts were fully phased in, they raised the after-tax incomes of the top 1 percent of households by 6.6 percent, compared to 2.6 percent for the middle 20 percent of households. The bottom 20 percent of households received the smallest cuts, with their after-tax incomes increasing by just 0.5 percent.TPC, “T10-0232 – Current Law; Baseline: Pre-EGTRRA Law; Distribution by Cash Income Percentile, 2010,” September 14, 2010, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/distributional-impact-bush-tax-cuts-2004-2010/current-law-baseline-pre-egtrra-law-12.

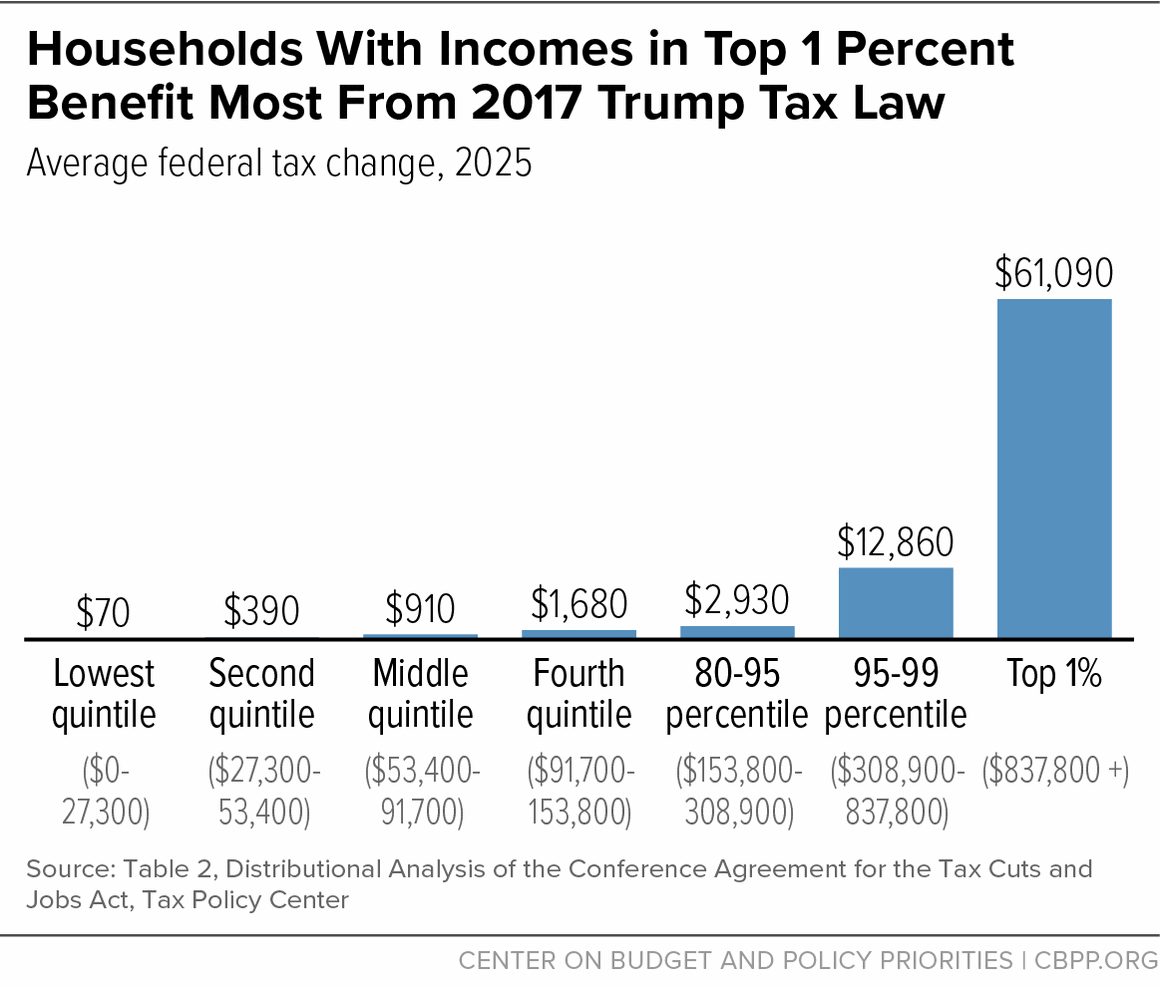

[10] 2025 is when the law is fully phased in and is before many provisions in the law are scheduled to expire. TPC, “T17-0314 - Conference Agreement: The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act; Baseline: Current Law; Distribution of Federal Tax Changes by Expanded Cash Income Percentile, 2025,” December 18, 2017, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/conference-agreement-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-dec-2017/t17-0314-conference-agreement.

[11] Due to racial barriers to economic opportunity, households of color are overrepresented among households with incomes in the bottom of the distribution, while non-Hispanic white households are heavily overrepresented among households with incomes at the top of the distribution. The 2017 law’s core provisions tilt heavily to households with incomes at the top of the distribution: white households in the highest-earning 1 percent receive 23.7 percent of the law’s total cuts, far more than the 13.8 percentage share that the bottom 60 percent of households of all races receive. Chye-Ching Huang and Roderick Taylor, “How the Federal Tax Code Can Better Advance Racial Equity,” CBPP, July 25, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/how-the-federal-tax-code-can-better-advance-racial-equity.

[12] Chuck Marr and Samantha Jacoby, “The Pass-Through Deduction Is Tilted Heavily to the Wealthy, Is Costly, and Should Expire as Scheduled,” CBPP, June 8, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/the-pass-through-deduction-is-tilted-heavily-to-the-wealthy-is-costly-and.

[13] The law also added a $10,000 cap on the deduction for state and local taxes (SALT). This has an offsetting effect for some taxpayers when combined with the law’s changes to the alternative minimum tax (AMT). See Kimberly A. Clausing and Natasha Sarin, “The Coming Fiscal Cliff: A Blueprint for Tax Reform in 2025,” The Hamilton Project, September 2023, https://www.hamiltonproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/20230927_THP_SarinClausing_FullPaper_Tax.pdf.

[14] The law doubled the Child Tax Credit’s maximum value from $1,000 to $2,000 per child but denied millions of children in families with low and moderate incomes the full increase. As of tax year 2022, roughly 19 million children get less than the full $2,000 Child Tax Credit or no credit at all because their families’ incomes are too low. TPC, “T22-0123 – Distribution of Tax Units and Qualifying Children by Amount of Child Tax Credit (CTC), 2022,” October 18, 2022, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/children-and-other-dependents-receipt-child-tax-credit-and-other-dependent-tax. Further, the law was estimated in 2017 to have ended the Child Tax Credit for about 1 million children who weren’t eligible for a Social Security number because of their immigration status but might have been claimed as tax dependents using an Individual Tax Identification Number. CBPP, “2017 Tax Law’s Child Credit: A Token or Less-Than-Full Increase for 26 Million Kids in Working Families,” August 27, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/2017-tax-laws-child-credit-a-token-or-less-than-full-increase-for-26-million-kids-in.

[15] The 2017 law permanently switched from the Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers (CPI-U) to the “chained” CPI to adjust tax brackets and certain provisions for inflation each year. The chained CPI generally rises more slowly over time than traditional the CPI-U. This slower growth erodes the value of certain provisions, such as the EITC, and is expected to push more taxpayers into higher tax brackets over time.

[16] TPC, “T22-0144 – Make the Individual Income Tax and Estate Tax Provisions in the 2017 Tax Act Permanent, by ECI Percentiles, 2026,” November 30, 2022, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/make-individual-income-tax-and-estate-tax-provisions-2017-tax-act-permanent-1.

[17] Ibid.

[18] TPC, “Distributional Analysis of the Conference Agreement for the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” December 18, 2017, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/publication/150816/2001641_distributional_analysis_of_the_conference_agreement_for_the_tax_cuts_and_jobs_act_0.pdf.

[19] Ibid.

[20] CBPP analysis of the 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF). In our SCF analysis, household income is market income (income from all sources except for Supplemental Security Income, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program).

[21] We will soon release a paper detailing the tax cuts this group received from the 2017 law.

[22] CBO, “The Distribution of Household Income, 2018,” August 4, 2021, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57061.

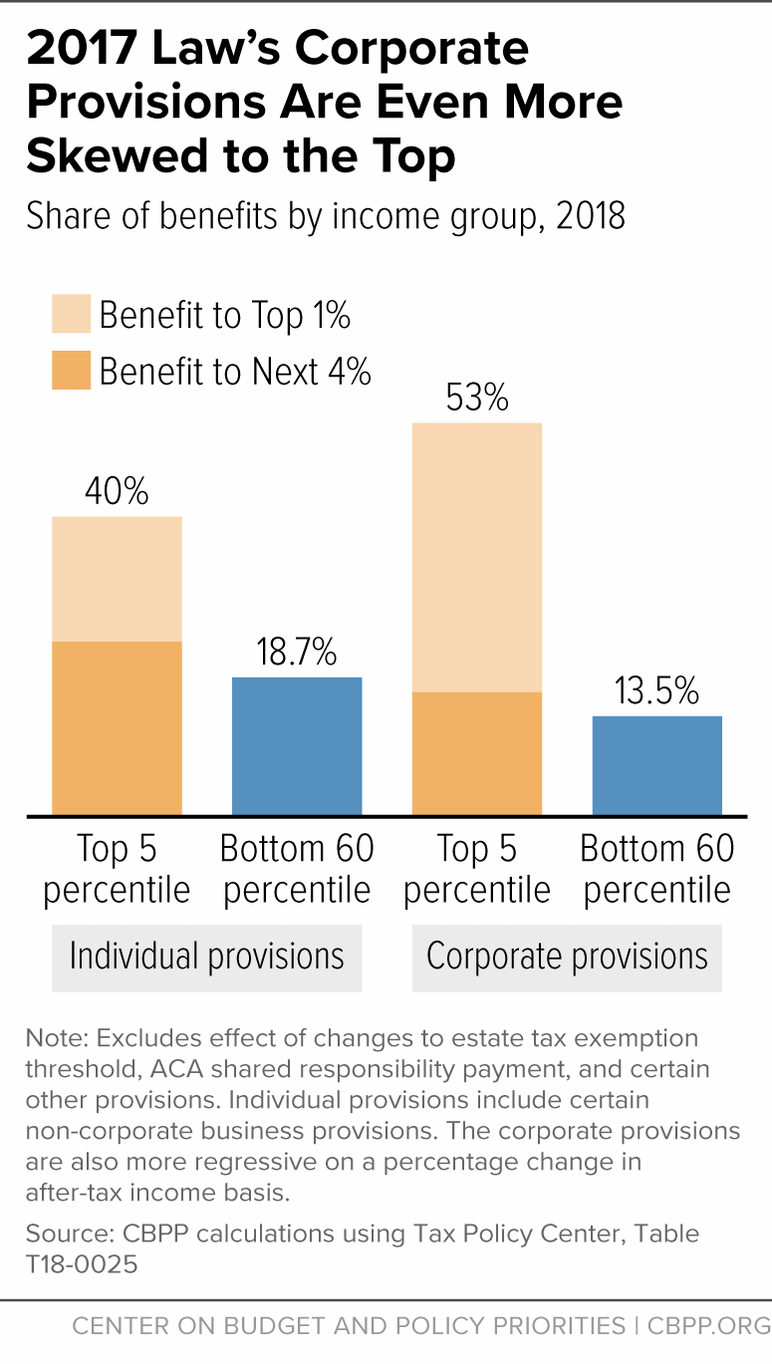

[23] TPC, “Table T18-0025 – The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA): All Provisions and Individual Income Tax Provisions, Distribution of Federal Tax Change by Expanded Cash Income Percentile, 2018,” February 16, 2018, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/individual-income-tax-provisions-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-tcja-february-2018/t18-0025. TPC’s analysis of the law’s individual income tax provisions includes the effect of certain pass-through business tax provisions, which business owners claim on their individual income tax returns.

[24] The Hamilton Project, “Taking on Tax: The past, present, and future,” September 27, 2023, https://www.hamiltonproject.org/event/taking-on-tax-policy/?_ga=2.26669821.1398658866.1707148521-1235817300.1707148521.

[25] Bobby Kogan, “Tax Cuts Are Primarily Responsible for the Increasing Debt Ratio,” Center for American Progress, March 27, 2023, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/tax-cuts-are-primarily-responsible-for-the-increasing-debt-ratio/.

[26] This figure is based on a compilation of CBO cost estimates that includes both the revenue and outlay effects of all major tax legislation enacted during the George W. Bush Administration. Based on analysis in Kathy Ruffing and Joel Friedman, “Economic Downturn and Legacy of Bush Policies Continue to Drive Large Deficits,” CBPP, February 28, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economic-downturn-and-legacy-of-bush-policies-continue-to-drive-large-deficits. For a detailed description of methodology used in this analysis, see box, “What Did Bush-Era Tax Cuts Cost through 2011?” in Kathy Ruffing and James R. Horney, “Downturn and Legacy of Bush Policies Drive Large Current Deficits,” CBPP, updated October 10, 2012, https://www.cbpp.org/research/downturn-and-legacy-of-bush-policies-drive-large-current-deficits.

[27] CBO, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018 to 2028.”

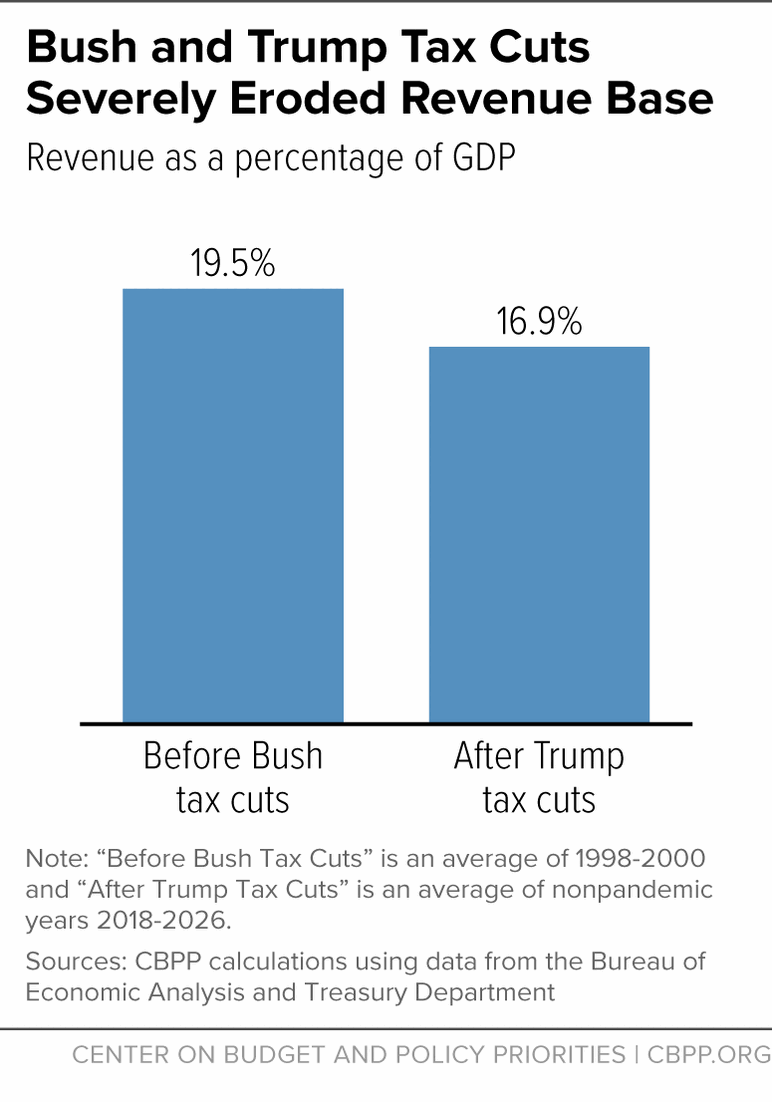

[28] Annual revenues averaged 16.8 percent as a share of GDP since 1946. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Federal Receipts as Percent of Gross Domestic Product,” February 28, 2024, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FYFRGDA188S.

[29] Paul N. Van de Water, “Federal Spending and Revenues Will Need to Grow in Coming Years, Not Shrink,” CBPP, September 6, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/federal-spending-and-revenues-will-need-to-grow-in-coming-years-not-shrink.

[30] CBO estimates that the cost of “major health care programs,” including Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, and the ACA, will rise to 6.7 percent of GDP in 2034, up from 4 percent in 2008.

[31] Van de Water, op. cit.

[32] OECD, “Poverty Rate (indicator),” 2024, https://data.oecd.org/inequality/poverty-rate.htm.

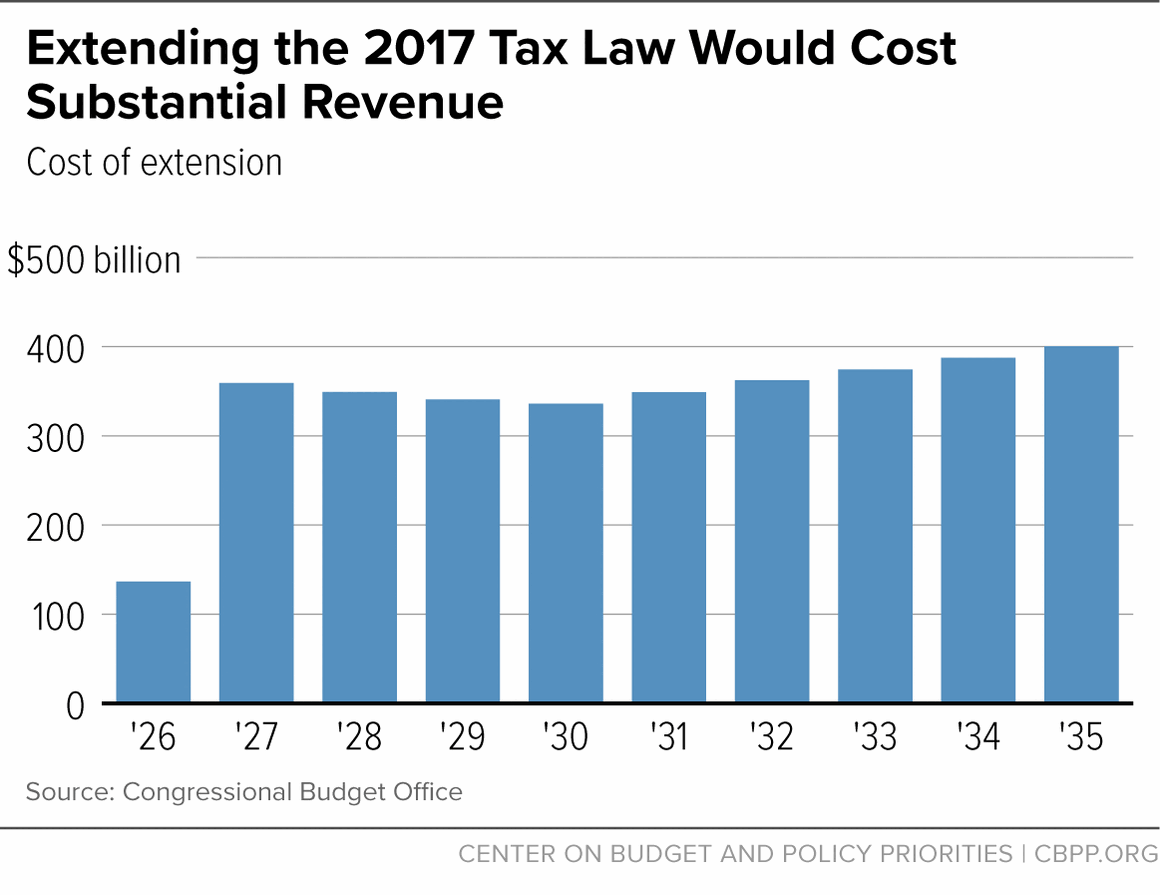

[33] CBPP calculations based on CBO, “Budgetary Outcomes Under Alternative Assumptions About Spending and Revenues.”

[34] Council of Economic Advisers, op. cit.

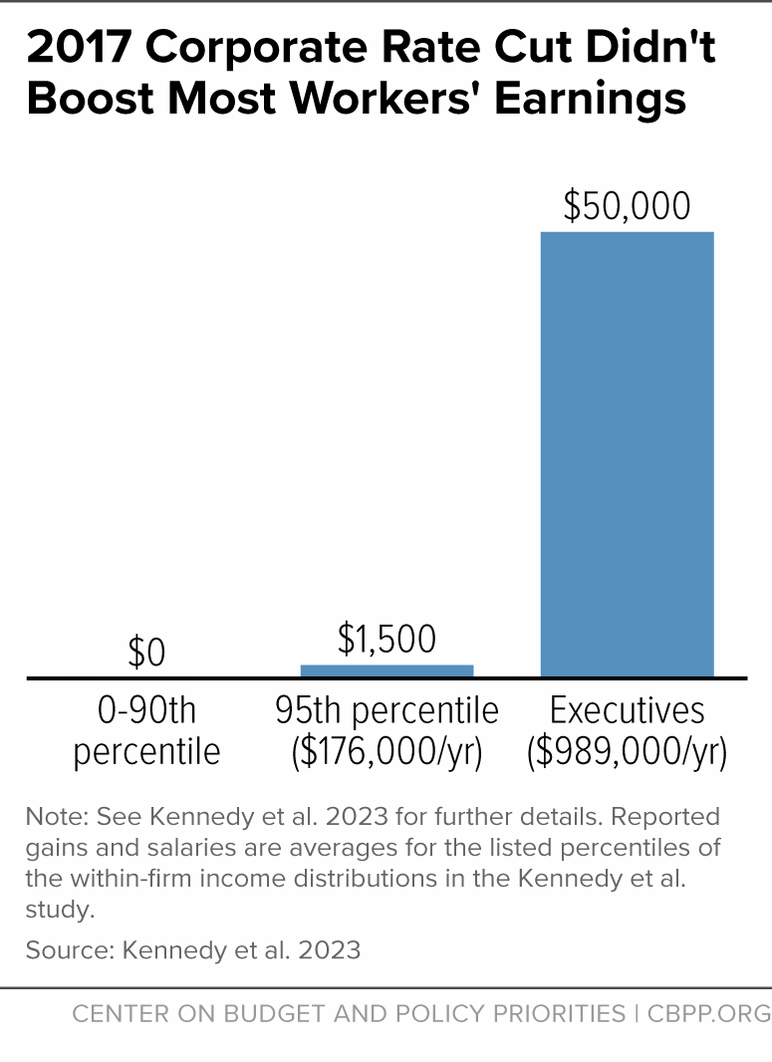

[35] Jane G. Gravelle and Donald J. Marples, “The Economic Effects of the 2017 Tax Revision: Preliminary Observations,” Congressional Research Service, updated June 7, 2019, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45736.

[36] William Gale and Claire Haldeman, “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act: Searching for supply-side effects,” Brookings Institution, July 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/20210628_TPC_GaleHaldeman_TCJASupplySideEffectsReport_FINAL.pdf.

[37] Kennedy et al., op. cit. The $114,000 threshold for the 90th percentile appears in an earlier version of the paper, dated December 9, 2022 (Table 5, Panel A). The sample period is 2013-2019, and gains from the tax cut are reported in nominal dollars.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Robert Gebeloff, “Who Owns Stocks? Explaining the Rise in Inequality During the Pandemic,” New York Times, January 26, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/26/upshot/stocks-pandemic-inequality.html.

[40] Gabriel Chodorow-Reich et al., “Tax Policy and Investment in a Global Economy,” NBER Working Paper, March 2024, https://www.nber.org/papers/w32180. The authors show that even when corporate tax cuts increase economic activity, there are countervailing, dynamic revenue impacts. On the one hand, more economic activity could expand the tax base and therefore increase tax collections; on the other, increased investment leads firms to take more depreciation deductions, which decreases tax collections. This study concludes that these two forces nearly offset in the near term, such that “the total revenue effect closely mirrors the mechanical corporate effect.” In the long run, the paper projects that dynamic effects could “close roughly 20 percent of the mechanical revenue decline.” Regarding claims that the 2017 tax law would pay for itself, see e.g., Kate Davidson, “Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin: GOP Tax Plan Would More Than Offset Its Cost,” Wall Street Journal, September 28, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/treasury-secretary-steven-mnuchin-gop-tax-plan-would-more-than-offset-its-cost-1506626980.

[41] Jim Tankersley, “Trump’s Tax Cut Fueled Investment but Did Not Pay for Itself, Study Finds,” New York Times, March 4, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/04/us/politics/trump-corporate-tax-cut.html.

[42] For example, around 70 percent of the income of partnerships, a common pass-through structure, flows to the top 1 percent of households. Michael Cooper et al., “Business in the United States: Who Owns It, and How Much Tax Do They Pay?” Tax Policy and the Economy, Vol. 30, No. 1, 2016, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/685594#.

[43] CBO, “The Distribution of Household Income, 2019,” November 15, 2022, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58353.

[44] IRS Statistics of Income, 2019, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-prior/p1304--2021.pdf.

[45] Steven Mufson, “Sen. Johnson Is a ‘No’ on the Tax Bill. He Says it Hurts Businesses (Like His Own),” Washington Post, November 16, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/sen-johnson-is-a-no-on-the-tax-bill-he-says-it-hurts-businesses-like-his-own/2017/11/16/c47b2a56-ca54-11e7-b0cf-7689a9f2d84e_story.html.

[46] Matthew J. Belvedere, “Mnuchin: GOP Tax Reform Would Give Small Business Owners the Lowest Rates ‘Since the 1930s,’” CNBC, November 17, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/11/17/mnuchin-gop-tax-plan-gives-small-business-lowest-rates-since-1930s.html.

[47] Goodman et al., op. cit.

[48] Marr and Jacoby, op. cit.

[49] Jason DeBacker et al., “The Impact of State Taxes on Pass-Through Businesses: Evidence from the 2012 Kansas Income Tax Reform,” September 29, 2017, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2958353. See also Michael Mazerov, “Kansas Provides Compelling Evidence of Failure of ‘Supply-Side’ Tax Cuts,” CBPP, January 22, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/kansas-provides-compelling-evidence-of-failure-of-supply-side-tax-cuts.

[50] Max Risch, “Trickle-Down Revisited,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 2023, https://www.law.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/2023-02/Trickle_Down_Feb14%20%281%29.pdf.