The share of jobless individuals receiving benefits through the regular federal-state unemployment insurance (UI) system has declined over several decades (excluding the temporary pandemic-related expansions that have now expired). Some of this decrease is attributable to UI failing to keep up with changes in the workforce since the system was established in the 1930s, including the increase of women in the workforce and the more recent rise of so-called gig workers. The biggest driver in declining UI coverage for at least the last decade, however, is the deliberate effort to reduce access to these benefits by many states, including several that have cut UI benefits in the wake of the COVID-19 recession.

After the Great Recession of 2007-2009, ten states reduced the number of weeks of regular unemployment benefits unemployed workers could receive, in some cases slashing the duration of benefits — which typically last 26 weeks — by more than half.[1] A similar pattern is beginning now. Four state legislatures passed legislation in 2022 to reduce the number of weeks of unemployment benefits, and others have actively considered such bills. More states may consider legislation next year.

These cuts will increase economic insecurity and hardship among workers who need UI while they look for their next job, reduce the UI system’s ability to respond to future economic shocks, and likely result in some individuals dropping out of the labor force (UI recipients generally must continually look for work to be eligible for benefits). Erecting additional barriers to unemployment benefits, especially those related to duration, also will disproportionately hurt workers of color who face greater barriers to employment and therefore experience longer average spells of joblessness. Finally, recent research illustrates that slashing unemployment benefits will not significantly boost employment, despite rhetoric to the contrary. The number of individuals claiming unemployment benefits is now at its lowest level in over 50 years, further indicating that UI is not holding back job growth.

Federal policymakers should establish basic national standards for coverage to give unemployed workers in all states adequate benefits when they need them, in a timely way, so a temporary stint of joblessness does not mean an immediate financial crisis for them and their families.

Enacted in 1935 as part of the Social Security Act, the unemployment insurance system is primarily administered and financed at the state level within general parameters established by federal law. Under this structure, states generally determine eligibility standards and benefit amounts. The percentage of unemployed workers receiving benefits under this system, while rising and falling somewhat based on prevailing economic conditions, generally hovered around 50 percent for much of the 1950s, and then declined in subsequent decades.[2] Preceding the 2020 recession, the UI recipiency rate had fallen to record lows of near 25 percent.

Recipiency rates vary considerably by state; before the pandemic, Florida and North Carolina served less than 11 percent of jobless workers while Massachusetts and New Jersey served roughly 50 percent. States can adopt broader or more restrictive eligibility criteria and can take administrative steps to make the system more or less accessible, all of which affect recipiency rates. Some of these variables include: the amount of past wages needed to be eligible for UI; whether all previous wages are counted when determining eligibility; whether an individual can leave work for a compelling family reason and be eligible; whether an individual can seek only part-time employment while receiving benefits; the severity of job search requirements; the accessibility of the UI application, including for those with language barriers; and the amount of time an individual is permitted to receive benefits.

Until 2009, every state provided at least a maximum of 26 weeks of regular, state-funded unemployment benefits. Now, ten states provide less, having made such cuts in the aftermath of the Great Recession. As discussed below, that count is now rising with Iowa, Kentucky, and Oklahoma recently enacting cuts to the weeks of benefits available to their workers.

States also set basic benefit levels and they, too, vary widely. Maximum weekly UI benefits are less than $250 in Arizona and Mississippi, while over $800 in Washington State and Massachusetts.

During economic downturns, the federal government usually provides additional federally funded weeks of unemployment benefits; during the Great Recession, the federal government also temporarily increased unemployment benefit amounts modestly.[3] In response to the recent pandemic-driven recession, Congress provided additional weeks of benefits, as well as far more substantial temporary increases in the weekly UI payment amount and significant expansions in UI eligibility that allowed tens of millions of people to access benefits who would have been ineligible under the regular program. These pandemic-related emergency UI programs ended nationwide the first weekend of September 2021, but about half of the states prematurely ended these federal benefits before that date.

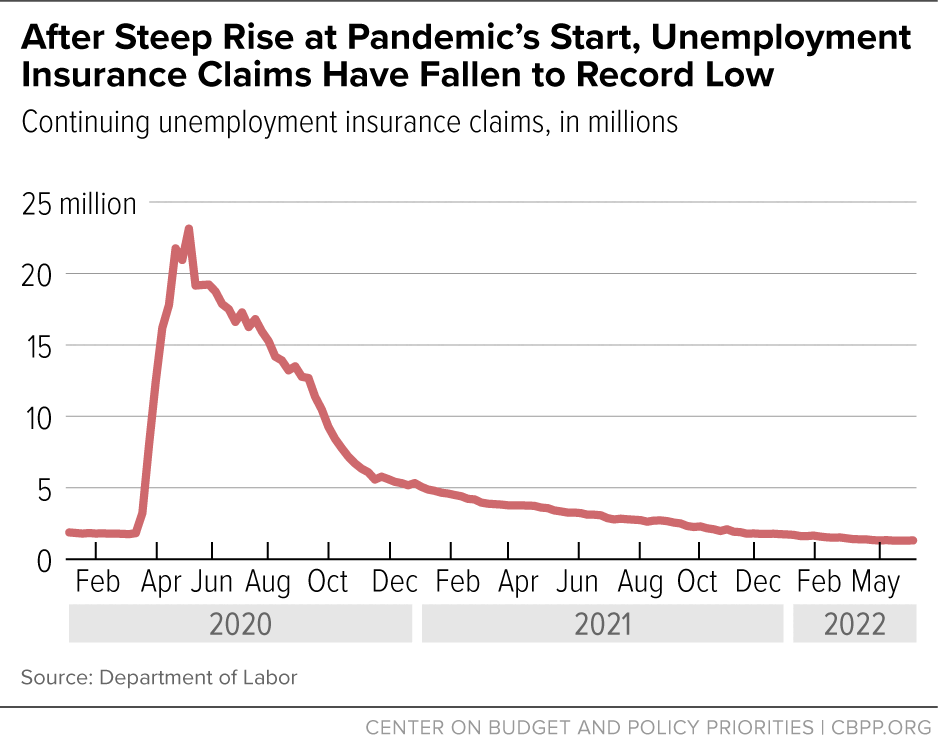

While the unemployment rolls soared in response to the economic shutdown caused by COVID-19, they have receded to record low levels as the economy has recovered. For the week ending June 11, just over 1.3 million jobless workers were receiving unemployment benefits nationwide, the lowest level since 1970.[4] (See Figure 1.)

Legislation has been introduced in 2022 in at least nine states, passing four legislatures so far, to take away unemployment benefits for workers who have lost their jobs through no fault of their own and are looking for new employment. These measures have primarily focused on reducing the number of weeks an individual may receive unemployment benefits. However, some states have considered other restrictive provisions, including requiring UI claimants to accept nearly any job, with little or no consideration of skills match, proximity, and wage levels.

Cuts to UI duration have followed two tracks: (1) a reduction in the number of weeks of UI in all economic circumstances; or (2) in a policy that has been described as indexing, cutting the number of weeks based on a state’s unemployment rate, or its rate of individuals claiming UI benefits.

Legislation from the four state legislatures passing UI restrictions so far this year — Kentucky, Iowa, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin — is summarized below. Bills to cut the duration of unemployment benefits and otherwise restrict access to UI also have been introduced this year in Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, and West Virginia.

In March, the Kentucky legislature passed HB 4, which cuts regular unemployment benefits by more than half, from 26 to 12 weeks.[5] Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear vetoed the bill, but his veto was overridden. Under the new statute, which will take effect January 1, 2023, the duration of regular unemployment benefits will vary based on the state’s unemployment rate (which is measured with a considerable lag). When the unemployment rate is below 4.5 percent, 12 weeks of benefits are available. Benefits rise by one week for every additional ½ point increase in the state’s unemployment rate and cannot exceed 24 weeks.

Under this formula, even if Kentucky’s unemployment rate doubled from its current level of 3.8 percent, the state would provide only 18 weeks of UI benefits, eight less than prior law. This scheme also includes a significant lag in time to trigger an increase in the duration of UI benefits based on rising unemployment. Finally, HB 4 significantly increases verified work search activities for UI recipients (up from one to five per week), and it requires individuals to accept a job paying at least 120 percent of their weekly UI benefit after receiving benefits for just six weeks.

The Iowa legislature passed an amended version of House File 2355 in April that reduces regular unemployment benefits from 26 weeks to 16 weeks.[6] This cut in benefits, which Governor Kim Reynolds signed into law on June 16, occurs regardless of the state’s unemployment rate (a longer benefit would be available in limited circumstances for business closings). The measure also requires a UI claimant to accept a job that pays lower wages than their prior job after just one week of UI benefits, rather than five. After just eight weeks of benefits, a UI claimant is required to accept a position that pays only 60 percent of their prior wage.

The Oklahoma legislature passed House Bill 1933 in May, and Governor Kevin Stitt signed the legislation into law on May 20. The measure will cut the duration of unemployment benefits from 26 weeks to 16 weeks for calendar years 2023 and 2024. Starting in 2025, the legislation will provide between 16 and 26 weeks of benefits, depending on the amount of UI claims in the state. Under the measure, the state will not provide 26 weeks of benefits unless the state’s weekly UI claims exceed 40,000, a threshold reached only three times for short periods since the 1980s, according to the Oklahoma Policy Institute.[7] Additionally, the claims data used to determine the benefit duration in the first half of a year will come from the third quarter of the prior year, creating a significant lag between any increase in joblessness and a rise in UI benefits.

The Wisconsin legislature passed Assembly Bill 937 in February; Governor Tony Evers vetoed the bill on April 15.[8] The legislation would cut the duration of regular unemployment benefits on a variable basis from 26 weeks down to 14 weeks, depending on the state’s unemployment rate. The number of weeks of benefits available would start at 14 when the state’s unemployment rate is 3.5 percent or less and rise by one week for every half-point increase in the unemployment rate until reaching 26 weeks of benefits when Wisconsin’s unemployment rate exceeds 9 percent.

The proposals to cut UI access in Kentucky, Iowa, Oklahoma, Wisconsin and several other states don’t account for basic facts about the unemployment insurance system. Some ignore individual workers’ needs, local differences, and barriers to employment. They mistakenly point to worker benefits as the cause of the system’s solvency problems and play into a narrative that workers who have lost jobs don’t want to find their next job expeditiously. They won’t help unemployed workers find jobs or protect their households against financial ruin during temporary periods of unemployment. Finally, they will weaken the ability of the UI system to respond to future recessions.

Cutting the duration of benefits based on a state’s unemployment rate fails to reflect individual needs, regional circumstances, and barriers to employment.

Spikes in unemployment may not generate a timely increase in benefits if the data used to determine the increase are many months old. One method used for linking a rise in unemployment to an increase in the duration of UI benefits is to compare the average unemployment rate in the first or second half of a year to the average rate in the third quarter of the prior year or the first quarter of the current year, respectively. This creates a significant delay — of up to nine months — between an increase in unemployment and a rise in the duration of benefits. For example, in his veto message of the Wisconsin legislation, Governor Evers highlighted that had the bill been in effect in April 2020, when the state’s unemployment rate was nearly 15 percent, a UI claimant would have been eligible for benefits based on the state’s unemployment rate in the third quarter of 2019, when its unemployment rate was barely above 3 percent. This would have resulted in just 14 weeks of benefits for an unemployed worker, rather than the state’s current 26 weeks.

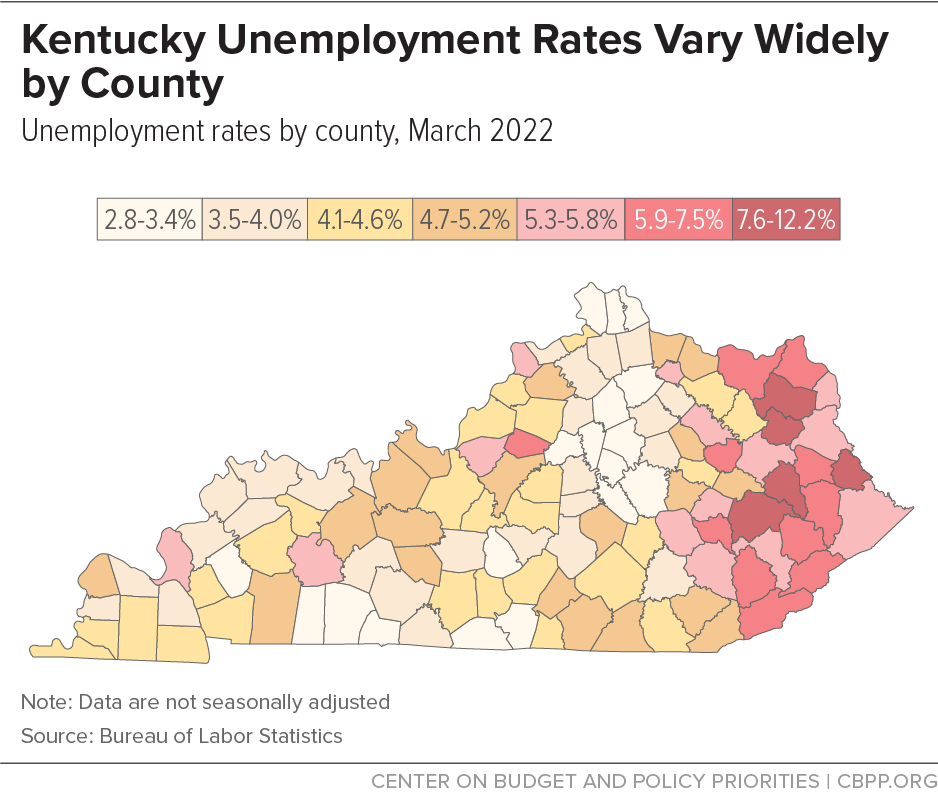

Statewide unemployment rates do not reflect much higher rates in certain portions of a state. In Kentucky, for example, the statewide unemployment rate was 4 percent in March 2022, but 15 mostly rural counties had rates at least 50 percent higher than the state average, ranging from 6.2 percent to 12.2 percent.[9] (See Figure 2.) Workers in these counties face more difficult labor markets and therefore may need longer to find new employment.

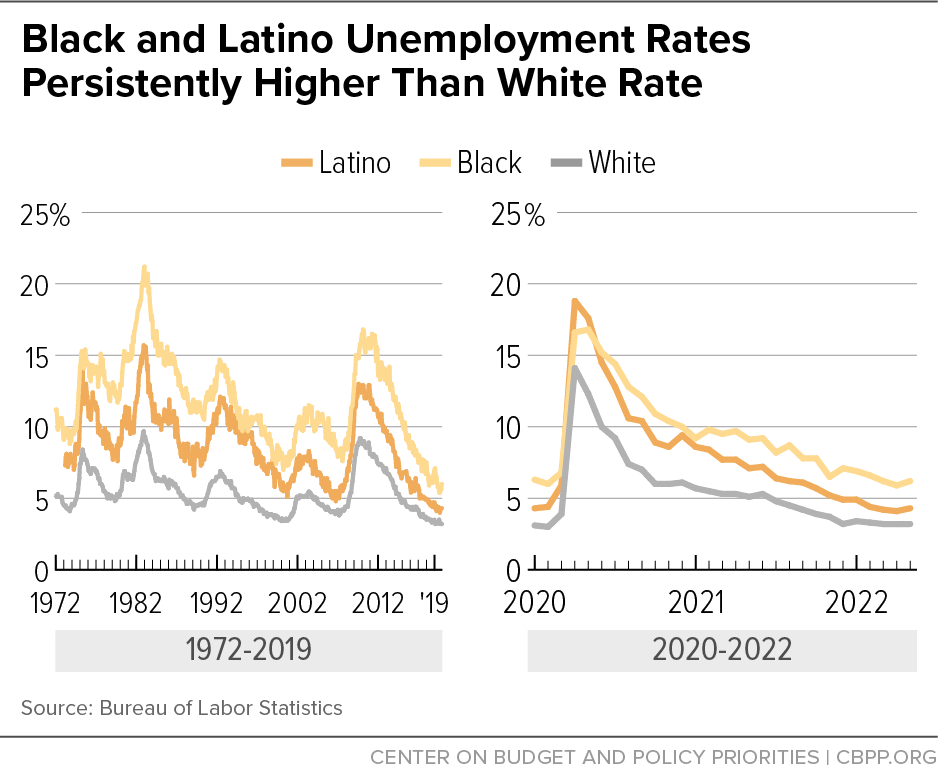

Basing benefit duration on general unemployment rates disproportionately affects workers of color. Black and Latino workers have consistently higher unemployment rates than white workers. (See Figure 3.) Furthermore, Black, Latino, and Asian workers all have longer average durations of unemployment than white workers, indicating that workers of color will disproportionately suffer from cuts to the duration of UI benefits.[10] These inequities stem from employment discrimination still present today and from other barriers to employment that people of color may be more likely to face — like less robust professional networks or fewer academic credentials — because of long-standing discrimination that has limited opportunities for many people of color.

Reductions in the number of weeks of benefits also disadvantage other groups of workers, including people with disabilities, whose unemployment rates are twice as high as those without a disability and who may face longer stints of unemployment as they seek work.

By providing adequate time for job searches, unemployment benefits help match workers with the jobs that they’re best suited for — given their education, talents, and experience, research finds.[11] This is good for: (1) workers, because they earn higher wages; (2) businesses, because it makes them more efficient; and (3) the overall economy, because it improves productivity.

Long-term UI solvency problems are linked to tax reductions for employers, not benefits for workers.

While the rapid, temporary increases in unemployment claims brought on by COVID-19 strained the current solvency of states’ UI trust funds, low and declining unemployment revenues prior to the pandemic are a greater long-term threat to both state trust funds’ solvency and the mission of the UI system. For example, Kentucky’s UI tax rate as a percentage of its total labor force was at an all-time low prior to the recent recession, according to the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy.[12]

In 2021, only eight states had employer UI tax rates sufficient to adequately finance their unemployment programs, the U.S. Department of Labor found.[13] The revenues states raise to finance UI benefits are maintained in dedicated trust funds, and when these funds become insolvent, states often borrow from the federal government to continue to pay benefits. Research has found that outdated limits on the amount of wages subject to UI taxes, known as the taxable wage base, has adversely affected UI solvency in many states.[14] The taxable wage base for federal UI taxes, which acts as a floor for state tax levels, has not been increased since 1983.

UI taxes are very modest in many states. For example, in Florida, businesses are charged between $7 and $378 per year for each employee.[15] (UI tax levels on employers are generally experience-rated, so that businesses laying off more workers pay higher rates.) By comparison, employers pay up to a maximum of $9,114 in annual Social Security taxes for each worker.

Lawmakers worried about rebuilding depleted UI trust funds before the next recession should focus first on raising UI taxes to more adequate levels, a key step to restoring the long-term health of UI systems. States that fail to do so could use federal recovery funds provided by the American Rescue Plan to shore up their trust funds rather than cut benefits.

Such investments of federal recovery dollars effectively reduce future taxes on employers and should therefore only be made when paired with reforms that make a state’s UI program more accessible and more equitable for workers. Instead, both Iowa and Kentucky used federal recovery funds to replenish their UI trust funds and then slashed the duration of UI benefits for workers.[16]

Cutting UI benefits will not boost employment, and it will hurt unemployed workers.

About half of the states prematurely ended federally funded unemployment benefits that were provided during the pandemic. Several studies concluded that increased hardship for jobless workers dwarfed any effect on employment from terminating these benefits.[17] For example, one study found that through the first week of August 2020, average UI benefits for workers in states ending pandemic unemployment benefits early fell by $278 per week, while earnings rose only by $14 per week, offsetting just 5 percent of the benefit loss.

The most recent research on this topic, released by Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco in April 2022, confirms that “UI withdrawals had limited direct impacts on hiring rates, which suggests the enhanced UI benefits were not an important source of labor shortages in 2021.”[18] With UI claims now at the lowest level in over 50 years, it makes even less sense to point to unemployment benefits as a major factor in any labor shortages.

Finally, regular unemployment benefits are not generous, providing a national average weekly benefit of just $363 in the last quarter of 2021.

Not all states are moving in the wrong direction. Using federal recovery funds, a few have pushed forward with proposals to increase access to unemployment benefits. For example, Colorado recently passed several UI improvements as part of an agreement to use $600 million in recovery funds to help restore the solvency of its UI trust fund.[19] These provisions will permanently allow UI recipients to earn more from part-time work without losing benefits, eliminate a one-week waiting period for UI benefits if the program is maintaining certain solvency standards, expand information on UI that employers provide to separated employees, and establish a benefit recovery fund to provide assistance to workers who have lost their job through no fault of their own but who do not receive unemployment benefits because of their immigration status.

Other states have focused federal recovery dollars on improving the UI system’s administrative infrastructure, including revising procedures for accepting claims and updating their IT systems. New Jersey, for example, has invested in making its UI application mobile-friendly and less complicated, upgrading and coordinating its program software, and hiring more staff to process claims.

Without congressional action, the weak UI system will be further eroded as states pursue cuts like those passed in Iowa, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin. Permanent, comprehensive UI reform would expand eligibility, raise benefit levels, and establish a floor of 26 weeks of UI in all states (with additional weeks available during recessions). To strengthen UI, policymakers should also improve the system’s financing, starting with an increase in the federal unemployment tax’s wage base. (Under the federal unemployment tax, employers pay taxes only on the first $7,000 of an employee’s wages per year, a level that has not been raised in 40 years.)

A shored-up UI system would better serve workers during normal economic times and would be ready to respond during recessions. The temporary measures that policymakers put in place after the pandemic hit provided enormous help for millions of workers and their families, but those measures didn’t work as well as they should have because the weak underlying UI system was overwhelmed by the number of jobless workers who needed help.

As occurred after the last recession, states are cutting their regular UI programs, especially the duration of benefits. Such changes will only further weaken a UI system that has provided assistance to fewer unemployed workers over time. The result will be higher poverty, greater racial disparities, and a reduced role in mitigating economic downturns. Federal legislation establishing basic national standards for coverage is needed to prevent any further erosion of the unemployment insurance system.