- Home

- How State Tax Policies Can Stop Increasi...

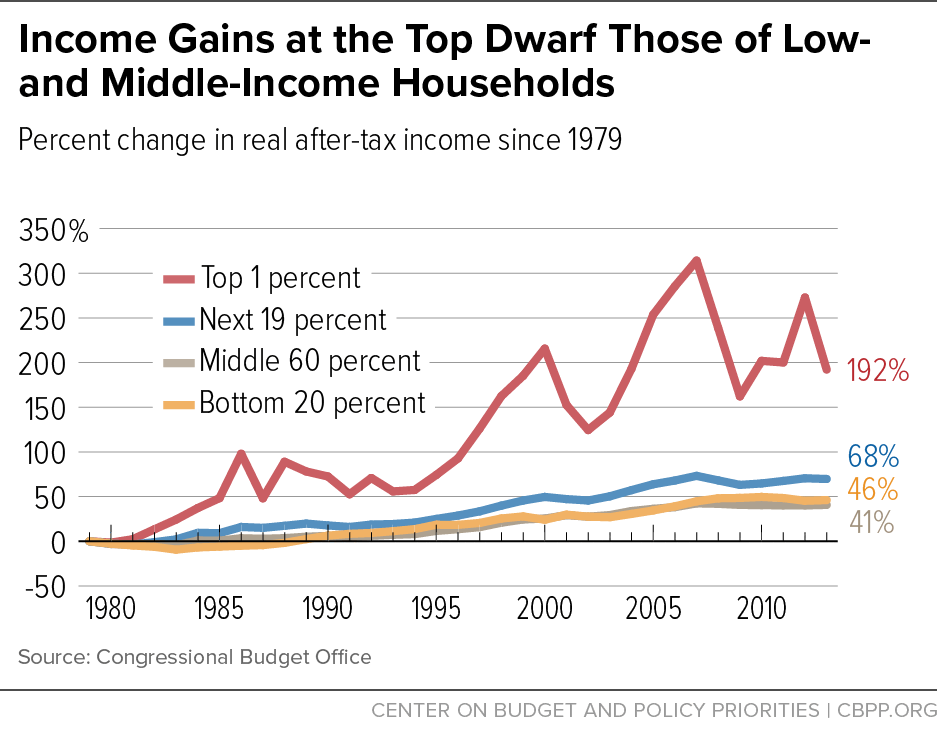

Income gains in the economy have accrued largely to the richest households, reducing opportunities for working people striving to get ahead.Over the last three and one-half decades, income gains in the American economy have accrued largely to the richest households, while many middle- and lower-income Americans haven’t shared in the nation’s growing prosperity. This has reduced opportunities for working people striving to get ahead and weakened our overall economy. Though the growth in inequality reflects a host of long-standing national and global economic trends that are largely outside state policymakers’ control (see box below), state policy choices can make matters worse or improve them.

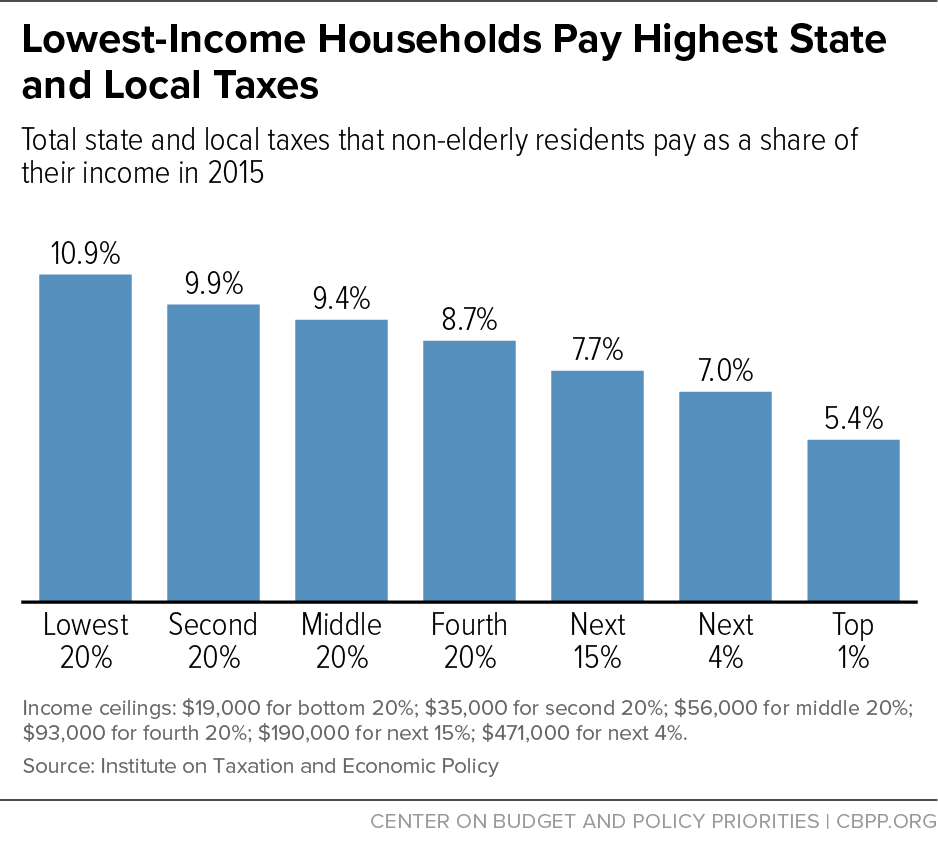

For example, virtually all states collect more taxes from moderate- and lower-income families, as a share of their income, than high-income families (see Figure 1). This increases inequality by reducing after-tax incomes more deeply among low- and middle-income families than high-income families.

The mechanisms by which state tax systems ask less of the wealthy than of poor and middle-income families have developed over time, often through closed-door negotiations resulting in special tax breaks that benefit a relative few. To reverse these trends, states should avoid actions — such as cutting income taxes or raising sales taxes — that worsen inequality by shifting taxes further to lower-income residents. Instead, they should ensure that high-income earners pay their share and lower-income earners don’t face increased tax responsibility. For example, states could:

- Make their income taxes more effective at reducing inequality through steps such as levying higher rates on high-income taxpayers or capping itemized deductions.

- Establish or expand taxes on inherited wealth, such as estate taxes.

- Strengthen taxes on corporations, such as by eliminating costly tax breaks — which enable many profitable corporations to pay zero state income taxes in some states where they do business — and establishing strong minimum taxes or adopting “combined reporting” (a reform that nullifies three of the most common state corporate tax shelters).

- Broaden the sales tax base to include more services purchased by wealthy individuals.

- Boost incomes among low- and moderate-wage working families by enacting state earned income tax credits.

- Maintain an overall tax system that raises sufficient revenue to pay for the building blocks of shared prosperity, such as education and access to health care.

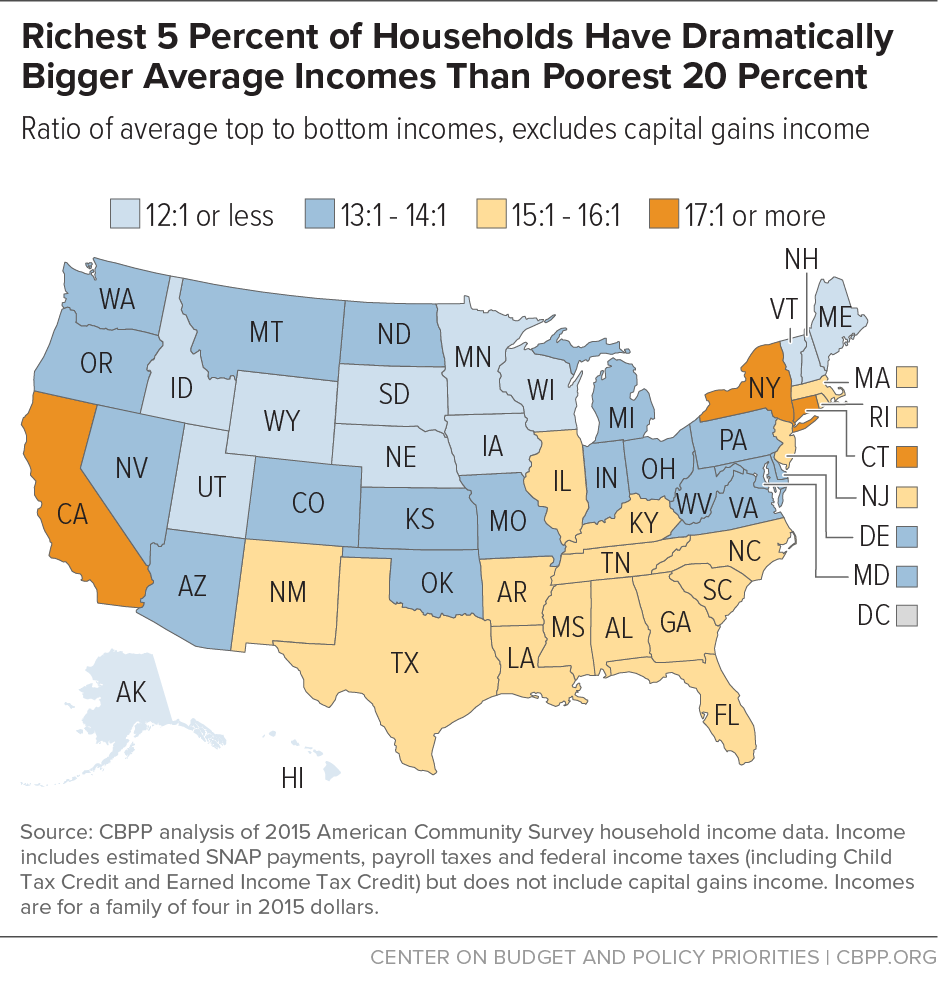

Across the country, the wealthiest residents have been the overwhelming beneficiaries of the uneven growth in incomes. The average income of the top 5 percent of households is now at least ten times that of the bottom 20 percent in every state, according to 2015 American Community Survey data. In the typical state, the average income of the top 5 percent was $325,928 compared to just $22,014 for the bottom 20 percent and $66,165 for the middle 20 percent. Moreover, these figures understate income disparities because they omit capital gains income, which is heavily concentrated among the richest households.[1] (Tables 1-4 provide comparative income data by state.)

The fact that the lion’s share of income gains has gone to the wealthiest residents contradicts the basic American belief that hard work should pay off — that the people who contribute to the nation’s economic growth should reap their share of the benefits of that growth. It also harms the health of those falling behind and diminishes educational opportunities for children growing up in less affluent areas. In short, such inequality is both a barrier to Americans striving to provide for themselves and their families and a drag on future economic growth. Reducing it should be a high priority for state policymakers.

Income Inequality Has Increased Dramatically Since 1970s

Today’s level of income inequality reflects three and a half decades of unequal income growth. The main facts of this story are well known.[2] The years from the end of World War II into the 1970s saw substantial economic growth and broadly shared prosperity. Incomes grew rapidly and at roughly the same rate up and down the income ladder, roughly doubling in inflation-adjusted terms between the late 1940s and early 1970s. The income disparity between the richest Americans and everyone else — while substantial — did not change much during this period.

Beginning in the 1970s, this pattern changed. Economic growth slowed and the income gap widened. Today, inequality between low- and high-income households — and between middle- and high-income households — is significantly greater than in the late 1970s. The concentration of income at the very top of the distribution has risen to levels last seen nearly a century ago, during the “Roaring Twenties.”

The income gains since the 1970s have gone disproportionately to the wealthiest households not only nationally, but in each state as well. (See Table 5.) The top 1 percent’s share of overall income rose in every state and the District of Columbia (and doubled nationally, from 10 percent to 20 percent) between 1979 and 2013, according to a recent analysis of IRS data.[3] Income inequality abated somewhat due to the Great Recession, but then resumed growing during the recovery. In 24 states, the top 1 percent captured at least half of all income growth between 2009 (when the recession officially ended) and 2013 (the most recent year for which state data on the top 1 percent are available).[4]

Why Is Inequality Worsening?

There are three broad reasons:

- Wages have become more unequal. This is by far the largest factor, since wages compose about three-quarters of total family income. Over the past four decades, wages have grown substantially at the top but only slowly if at all at the bottom and in the middle. Longer periods of high unemployment have left workers with less leverage when asking for higher pay. More intense competition from foreign firms and a decline in higher-paying manufacturing jobs have also slowed wage growth at the bottom and middle of the wage scale. Falling union membership has weakened the position of working households, as well. At the same time, the typical worker is more skilled and experienced and thus contributes more to the economy’s productivity growth but has less to show for it.a

- Investment income has become a bigger slice of the economic pie. Income from investments, such as capital gains, dividends, interest, and rent, goes primarily to high-income households, so the growth in investment income as a share of overall income has widened the gap between the wealthy and everyone else. (Our measure of household income doesn’t include capital gains because of data limitations, so our report almost certainly underestimates the rise in inequality in recent decades.)

- Government actions — and in some cases inaction — have also played a role. The federal minimum wage provides an important backstop to declining wages, but policymakers have failed to maintain its purchasing power over time; it has shrunk by 25 percent since 1968 due to inflation. Also, the safety net has weakened — most notably, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) helps many fewer needy families than it used to — and the federal and state governments have provided insufficient support for workers’ collective bargaining rights. Changes in federal, state, and local tax policy have, in many cases, made things worse.

For more details, see Chad Stone et al., A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 7, 2016; Josh Bivens et al., “Raising America’s Pay: Why It’s Our Central Economic Policy Challenge,” Economic Policy Institute, June 4, 2014; Elizabeth McNichol et al., “Pulling Apart: A State-by-State Analysis of Income Trends,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 15, 2012; Larry Mishel et al., “State of Working America,” Economic Policy Institute, 2012.

a Since the 1970s, the Labor Quality Index, a measure of workers’ aggregate contribution to productivity growth based on their skills, experience, and education, has grown steadily but median pay has stagnated.

Worsening inequality is not inevitable. In the later part of the 1990s, for example, this picture improved modestly, as persistent low unemployment, an increase in the minimum wage, and rapid productivity growth fueled real wage gains at the bottom and middle of the income scale. Those few years of more broadly shared growth were insufficient to counteract the decades-long pattern of growing inequality. Low- and moderate- income families are once again seeing income growth. With the continued drop in unemployment, incomes grew dramatically across the board in 2015, and the incomes of low- and moderate-income households have finally returned close to pre-recession levels.[5] If this more broadly shared income growth continues — and if federal and state policies provide an added boost — the growth in income inequality will likely slow and could reverse.

A Snapshot of Inequality in the States

The concentration of incomes among the wealthiest residents is striking in every state, even without taking capital gains income — which is heavily concentrated among the richest households — into account:[6]

- In every state, the average income of the top 5 percent of households is at least ten times that of the bottom 20 percent, according to 2015 American Community Survey data. The ten states with the largest disparities are New York, California, Connecticut, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Illinois, New Jersey, Florida, Georgia, and Texas.

- In the nation, the average income of the richest 5 percent of families ($325,928) dwarfs that of the poorest 20 percent ($22,014) and middle-income families ($66,165).

- In the typical (median) state, the richest 5 percent of households receive 19 percent of income in the state.

- In 19 states, the top 20 percent of households receive more than 45 percent of all income in the state.

Table 1 and Figure 3 compare the average incomes of the top 5 percent and bottom 20 percent of families in each state. Table 2 compares the average incomes of the top 20 percent and bottom 20 percent of families. Table 3 shows the share of income received by each fifth of families. Table 4 shows the average income by fifth for each state.

Methodology

This analysis uses the latest (2015) household income data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) to measure the post-federal-tax incomes of high-, middle- and low-income households. Estimated Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program payments were added to household income, which is adjusted for payroll taxes and federal income taxes (including the Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit). Note that ACS income data do not include capital gains. Average incomes were adjusted for household size before being sorted into quintiles; average incomes shown are for a family of four in 2015 dollars. See the appendix for more details.

State Tax Policy Can Push Back Against Growing Inequality

Nearly every state collects more taxes from poor families than high-income families, relative to their incomes. States (including their local governments) also generally collect more taxes from middle-income families than high-income families.[7] These disparities increase income inequality by reducing the after-tax incomes of low- and middle-income families more deeply than those of high-income families.

No single decision resulted in this inequitable treatment. Rather, in a series of policy decisions reaching back more than a century, state policymakers have tended to choose tax policies that favor the wealthy over the poor and favor corporations over workers.

Many major state taxes were first put in place in the first half of the 20th Century, a period in which many Americans (especially African Americans in the South) were barred from voting, and in which urban areas in many states were underrepresented in state legislatures. Moreover, right up to the present, a small number of legislators and staff typically construct tax policy in most state legislatures, often with the input of corporate lobbyists. And state tax policy is sufficiently arcane that many policy decisions do not receive the broad attention they deserve, particularly when their immediate revenue effects are modest.

As a result, state tax codes are regressive, meaning low- and middle-income families pay a bigger share of their income in taxes than wealthy families. In 2015, the poorest fifth of married, non-elderly families paid twice as large a share of their incomes in state and local taxes as the wealthiest 1 percent of such families, on average (10.9 percent versus 5.4 percent).[8]

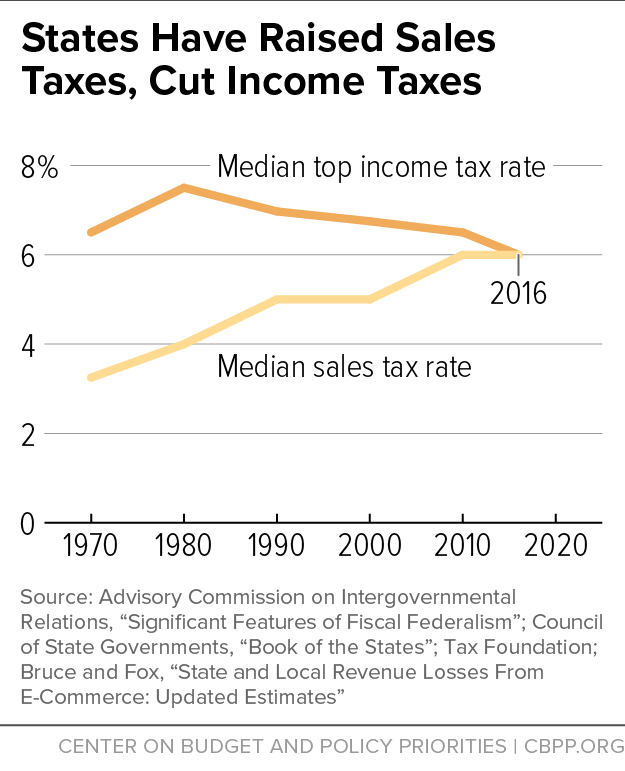

One major reason is that most states rely heavily on sales taxes. Sales taxes disproportionately affect low-income families, largely because they spend (rather than save or invest) a larger share of their income than higher-income families do. Property taxes also generally hit low- and middle-income families more heavily than high-income families.

The income tax is the one major state revenue source that typically reduces inequality, but many states have weak income tax systems that do too little in this regard. A graduated-rate income tax, which taxes higher incomes at higher rates, affects high-income families more than low-income families, and in a few states this balances out the effects of sales and property taxes. But many state income taxes are flat (meaning all income is taxed at the same rate) or nearly flat, and a few states don’t have an income tax. As a result, some states do much more than others to reduce inequality through their tax codes.

Many states have made their tax systems even more out of balance since the late 1970s, even as inequality has risen, by increasing their reliance on sales taxes rather than income taxes. For example, the sales tax rate in the typical state has doubled since 1970 while the top income tax rate has remained unchanged.[9] (See Figure 4.)

The shift away from states taxing the wealthy has continued since the Great Recession hit. In the depths of the downturn in 2009 and 2010, for example, a number of states raised taxes as part of their response to recession-induced revenue declines, but while they raised both income taxes and sales taxes, the income tax increases were almost uniformly temporary while half of the sales tax-rate increases were permanent. Some states have cut income taxes as the economy recovers.

States can reverse these trends and use tax policy to reduce income inequality by taking the following actions.

- Strengthen their income tax’s inequality-reducing impact. Tax increases on high-income individuals — who are best able to afford the higher tax and least likely to spend substantially less as a result of the increase — can reduce inequality directly while raising revenue to invest in a more broadly prosperous future. Policymakers can raise taxes on high-income households by raising income tax rates at the top end and by capping itemized deductions and other tax breaks for high-income taxpayers.

- Establish or expand taxes on inherited wealth, such as the estate tax. Only the very wealthiest taxpayers pay estate taxes — just 2.56 percent of estates, on average, in the states with the tax. Some 18 states plus Washington, D.C. have an estate or inheritance tax. States with an estate tax can avoid increasing inequality by resisting calls to reduce or eliminate the tax. States without an estate tax can reduce inequality by adopting one.

- Eliminate costly and ineffective tax breaks for corporations. State corporate income taxes are declining; the share of tax revenue supplied by this tax in the 45 states that levy it fell from nearly 10 percent in the late 1970s, to only a little more than 5 percent today. Many profitable corporations pay nothing in state income taxes in some states where they do business. States can strengthen taxes on corporations by carefully examining and eliminating costly tax breaks. They can also establish strong minimum taxes — a floor on the amount of tax owed each year. In addition, states that have not already done so can adopt a reform known as combined reporting, which nullifies three of the most common state corporate tax shelters.[10] Evidence does not support the claim that these kinds of changes will drive large numbers of affluent people and businesses to other states.[11]

- Broaden the sales tax base. States can make their tax systems fairer by broadening the sales tax base to include more services that high-income families consume, such as investment counseling or country club memberships. While this would shift more of the responsibility for paying the sales tax to wealthier families, the effect would be relatively small; states should accompany such changes by other measures that go further to reduce inequality.

-

Enact state earned income tax credits. States can boost the incomes of low- and moderate-wage working families or offset the impact on these families of other tax changes by enacting or expanding a state earned income tax credit (EITC). Many states have created EITCs to build on the strengths of the federal EITC, which offsets low-wage workers’ payroll taxes, supplements the earnings of low- and moderate-income families, and helps families move from welfare to work. [12]

Over half of the states with an income tax and one state without an income tax — in all, 26 states plus the District of Columbia — have established EITCs.[13]

-

Avoid costly tax shifts and tax cuts aimed at the wealthy. Public discussions about strengthening the economy often center on tax cuts, despite growing evidence that they don’t create many jobs or promote broad prosperity.[14] Maintaining and improving schools, transportation networks, and other public services shown to generate growth will require resources, both now and in the future.

As state revenues slowly recover from the Great Recession, some states, such as Louisiana and North Carolina, have considered extreme tax changes such as replacing the income tax with a higher, broader sales tax. That would sharply raise taxes for low- and middle-income households and threaten the state’s ability to maintain many of the services necessary to assist families left behind in the current economy. Other states, such as Kansas, Mississippi, and North Carolina, have deeply cut income taxes for individuals and businesses without replacing the lost revenues, which over time will force drastic cuts in services like schools, transportation, and public safety.

Many states have enacted less extreme but still costly income tax cuts that benefit individuals at the top and profitable businesses but do little or nothing for low- and middle-income households and damage the state’s ability to invest in more effective ways.

If these trends continue, they will tilt state tax systems even more against low- and middle-income households. States choosing to cut taxes as the economy grows can do so while reducing the impact of their taxes on low- and moderate-income families by enacting tax credits targeted to low-income taxpayers or by raising the personal exemption or standard deduction, rather than cutting top income tax rates or capital gains taxes.

| TABLE 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Richest 5 Percent of Households Have Dramatically Bigger Incomes Than Poorest Households (Figures exclude capital gains) | ||

| Ratio of Avg. Income for Richest 5% to Poorest 20% of Households | Rank | |

| New York | 19.90 | 1 |

| California | 16.73 | 2 |

| Connecticut | 16.60 | 3 |

| Louisiana | 15.84 | 4 |

| Massachusetts | 15.76 | 5 |

| Illinois | 15.64 | 6 |

| New Jersey | 15.61 | 7 |

| Florida | 15.60 | 8 |

| Georgia | 15.55 | 9 |

| Texas | 15.44 | 10 |

| Kentucky | 15.24 | 11 |

| New Mexico | 14.89 | 12 |

| Mississippi | 14.77 | 13 |

| North Carolina | 14.71 | 14 |

| Tennessee | 14.69 | 15 |

| Alabama | 14.63 | 16 |

| South Carolina | 14.62 | 17 |

| Arkansas | 14.54 | 18 |

| Rhode Island | 14.50 | 19 |

| Oklahoma | 14.40 | 20 |

| Virginia | 14.31 | 21 |

| Arizona | 14.22 | 22 |

| Pennsylvania | 13.84 | 23 |

| Maryland | 13.57 | 24 |

| Michigan | 13.38 | 25 |

| Ohio | 13.25 | 26 |

| Delaware | 13.23 | 27 |

| Missouri | 13.07 | 28 |

| Kansas | 13.06 | 29 |

| Colorado | 13.00 | 30 |

| Montana | 12.98 | 31 |

| Washington | 12.87 | 32 |

| Oregon | 12.87 | 33 |

| North Dakota | 12.81 | 34 |

| West Virginia | 12.76 | 35 |

| Nevada | 12.61 | 36 |

| Indiana | 12.47 | 37 |

| Minnesota | 12.32 | 38 |

| Vermont | 11.95 | 39 |

| Nebraska | 11.81 | 40 |

| Iowa | 11.69 | 41 |

| Idaho | 11.47 | 42 |

| Maine | 11.46 | 43 |

| South Dakota | 11.32 | 44 |

| Wisconsin | 11.20 | 45 |

| Wyoming | 11.16 | 46 |

| Alaska | 11.05 | 47 |

| New Hampshire | 10.61 | 48 |

| Hawaii | 10.42 | 49 |

| Utah | 10.34 | 50 |

| District of Columbia | 28.24 | |

| United States | 14.81 | |

Source: CBPP analysis of 2015 American Community Survey (ACS) data Note: ACS income data do not include capital gains. Households were size-adjusted before being sorted into quintiles.

| TABLE 2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Richest 20 Percent of Households Have Dramatically Bigger Incomes Than Poorest Households (Figures exclude capital gains) | ||

| Ratio of Avg. Income for Richest 20% to Poorest 20% of Households | Rank | |

| New York | 10.84 | 1 |

| California | 9.83 | 2 |

| Louisiana | 9.61 | 3 |

| Connecticut | 9.51 | 4 |

| New Jersey | 9.42 | 5 |

| Massachusetts | 9.42 | 6 |

| New Mexico | 9.18 | 7 |

| Georgia | 9.14 | 8 |

| Illinois | 9.12 | 9 |

| Mississippi | 8.95 | 10 |

| Texas | 8.95 | 11 |

| Alabama | 8.9 | 12 |

| Rhode Island | 8.83 | 13 |

| Virginia | 8.83 | 14 |

| Florida | 8.82 | 15 |

| Kentucky | 8.78 | 16 |

| North Carolina | 8.64 | 17 |

| South Carolina | 8.63 | 18 |

| Arizona | 8.56 | 19 |

| Tennessee | 8.51 | 20 |

| Arkansas | 8.49 | 21 |

| Oklahoma | 8.31 | 22 |

| Maryland | 8.27 | 23 |

| Pennsylvania | 8.26 | 24 |

| Michigan | 8.1 | 25 |

| Delaware | 8.08 | 26 |

| West Virginia | 8.04 | 27 |

| Ohio | 7.95 | 28 |

| Washington | 7.85 | 29 |

| Oregon | 7.81 | 30 |

| Colorado | 7.81 | 31 |

| Montana | 7.69 | 32 |

| Missouri | 7.67 | 33 |

| Kansas | 7.61 | 34 |

| Nevada | 7.51 | 35 |

| Indiana | 7.41 | 36 |

| North Dakota | 7.35 | 37 |

| Minnesota | 7.23 | 38 |

| Iowa | 7.06 | 39 |

| Maine | 7.05 | 40 |

| Nebraska | 7.01 | 41 |

| Vermont | 6.97 | 42 |

| Idaho | 6.92 | 43 |

| Alaska | 6.88 | 44 |

| New Hampshire | 6.77 | 45 |

| Wisconsin | 6.71 | 46 |

| South Dakota | 6.71 | 47 |

| Hawaii | 6.62 | 48 |

| Wyoming | 6.53 | 49 |

| Utah | 6.37 | 50 |

| District of Columbia | 16.31 | |

| United States | 8.71 | |

Source: CBPP analysis of 2015 American Community Survey (ACS) data

Note: ACS income data do not include capital gains. Households were size-adjusted before being sorted into quintiles.

| TABLE 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richest Households Capture Largest Share of Income (Figures exclude capital gains) | |||||||

| Bottom 20% | Lower 20% | Middle 20% | Next 20% | Top 20% | (Next 15%) | (Top 5%) | |

| Alabama | 5.0% | 10.5% | 16.0% | 23.5% | 44.9% | 26.4% | 18.5% |

| Alaska | 6.1% | 11.5% | 16.6% | 23.6% | 42.2% | 25.3% | 16.9% |

| Arizona | 5.3% | 10.6% | 15.8% | 22.9% | 45.3% | 26.5% | 18.8% |

| Arkansas | 5.4% | 10.7% | 15.8% | 22.7% | 45.5% | 26.0% | 19.5% |

| California | 4.9% | 9.6% | 14.9% | 22.6% | 48.0% | 27.6% | 20.4% |

| Colorado | 5.7% | 11.0% | 16.3% | 22.7% | 44.3% | 25.8% | 18.4% |

| Connecticut | 4.9% | 10.3% | 15.8% | 22.4% | 46.6% | 26.2% | 20.3% |

| Delaware | 5.4% | 11.4% | 16.7% | 23.1% | 43.4% | 25.7% | 17.8% |

| Florida | 5.3% | 10.4% | 15.3% | 22.3% | 46.7% | 26.1% | 20.7% |

| Georgia | 5.1% | 10.3% | 15.5% | 22.7% | 46.4% | 26.7% | 19.7% |

| Hawaii | 6.2% | 12.0% | 17.2% | 23.3% | 41.3% | 25.0% | 16.2% |

| Idaho | 6.2% | 11.6% | 16.4% | 22.7% | 43.0% | 25.2% | 17.8% |

| Illinois | 5.1% | 10.4% | 15.7% | 22.8% | 46.1% | 26.3% | 19.8% |

| Indiana | 5.9% | 11.3% | 16.4% | 22.9% | 43.5% | 25.2% | 18.3% |

| Iowa | 6.0% | 11.8% | 16.8% | 22.8% | 42.6% | 25.0% | 17.6% |

| Kansas | 5.8% | 11.1% | 16.2% | 22.7% | 44.2% | 25.2% | 19.0% |

| Kentucky | 5.2% | 10.7% | 15.9% | 22.8% | 45.4% | 25.7% | 19.7% |

| Louisiana | 4.8% | 10.1% | 15.7% | 23.5% | 46.0% | 27.0% | 18.9% |

| Maine | 6.1% | 11.5% | 16.5% | 22.9% | 43.0% | 25.5% | 17.5% |

| Maryland | 5.3% | 11.1% | 16.4% | 23.1% | 44.0% | 26.0% | 18.1% |

| Massachusetts | 4.8% | 10.6% | 16.4% | 23.2% | 45.0% | 26.2% | 18.8% |

| Michigan | 5.4% | 11.0% | 16.3% | 23.2% | 44.1% | 25.9% | 18.2% |

| Minnesota | 6.0% | 11.4% | 16.6% | 22.6% | 43.4% | 24.9% | 18.5% |

| Mississippi | 5.0% | 10.8% | 16.0% | 23.5% | 44.7% | 26.3% | 18.4% |

| Missouri | 5.8% | 11.2% | 16.1% | 22.7% | 44.2% | 25.4% | 18.8% |

| Montana | 5.7% | 11.3% | 16.5% | 22.8% | 43.8% | 25.3% | 18.5% |

| Nebraska | 6.1% | 11.5% | 16.6% | 22.8% | 43.0% | 24.9% | 18.1% |

| Nevada | 5.9% | 11.2% | 16.1% | 22.8% | 44.0% | 25.5% | 18.5% |

| New Hampshire | 6.2% | 12.0% | 16.9% | 23.0% | 42.0% | 25.5% | 16.4% |

| New Jersey | 4.9% | 10.2% | 16.0% | 23.1% | 45.8% | 26.8% | 19.0% |

| New Mexico | 5.0% | 10.4% | 15.5% | 23.2% | 46.0% | 27.3% | 18.6% |

| New York | 4.5% | 9.5% | 15.0% | 22.2% | 48.8% | 26.4% | 22.4% |

| North Carolina | 5.3% | 10.4% | 15.6% | 22.8% | 45.9% | 26.3% | 19.5% |

| North Dakota | 5.8% | 11.6% | 16.9% | 22.7% | 43.0% | 24.2% | 18.7% |

| Ohio | 5.5% | 11.1% | 16.5% | 23.1% | 43.8% | 25.6% | 18.3% |

| Oklahoma | 5.5% | 10.9% | 15.9% | 22.4% | 45.4% | 25.7% | 19.7% |

| Oregon | 5.7% | 10.8% | 16.1% | 22.9% | 44.5% | 26.2% | 18.3% |

| Pennsylvania | 5.4% | 10.9% | 16.2% | 22.9% | 44.6% | 25.9% | 18.7% |

| Rhode Island | 5.0% | 10.6% | 16.5% | 23.5% | 44.4% | 26.2% | 18.2% |

| South Carolina | 5.2% | 10.8% | 16.0% | 23.0% | 45.0% | 26.0% | 19.1% |

| South Dakota | 6.3% | 12.1% | 16.9% | 22.6% | 42.1% | 24.3% | 17.8% |

| Tennessee | 5.3% | 10.7% | 15.8% | 22.7% | 45.5% | 25.9% | 19.6% |

| Texas | 5.2% | 10.2% | 15.3% | 22.6% | 46.7% | 26.6% | 20.2% |

| Utah | 6.6% | 11.9% | 16.6% | 22.6% | 42.2% | 25.1% | 17.1% |

| Vermont | 6.2% | 11.6% | 16.4% | 22.4% | 43.4% | 24.8% | 18.6% |

| Virginia | 5.1% | 10.5% | 15.9% | 23.0% | 45.4% | 27.0% | 18.4% |

| Washington | 5.6% | 10.9% | 16.2% | 23.1% | 44.2% | 26.1% | 18.1% |

| West Virginia | 5.4% | 11.2% | 16.8% | 23.6% | 43.1% | 26.0% | 17.1% |

| Wisconsin | 6.3% | 11.8% | 17.0% | 22.9% | 42.1% | 24.5% | 17.6% |

| Wyoming | 6.4% | 11.9% | 16.7% | 22.8% | 42.0% | 24.1% | 18.0% |

| District of Columbia | 3.1% | 8.1% | 14.3% | 23.33% | 51.2% | 29.0% | 22.15% |

| United States | 5.3% | 10.5% | 15.8% | 22.8% | 45.7% | 26.3% | 19.4% |

Source: CBPP analysis of 2015 American Community Survey (ACS) data

Note: ACS income data do not include capital gains. Households were size-adjusted before being sorted into quintiles. Average incomes shown are for a family of four in 2015 dollars

| TABLE 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Household Income in 2015 by Quintile, for Family of Four (Figures exclude capital gains) | ||||||

| Bottom 20% | Lower 20% | Middle 20% | Next 20% | Top 20% | (Top 5%) | |

| Alabama | $17,486 | $36,385 | $55,585 | $81,551 | $155,646 | $255,862 |

| Alaska | 28,439 | 53,159 | 76,840 | 109,484 | 195,687 | 314,268 |

| Arizona | 20,005 | 40,113 | 59,852 | 86,587 | 171,287 | 284,503 |

| Arkansas | 17,879 | 35,596 | 52,674 | 75,637 | 151,847 | 259,930 |

| California | 22,110 | 43,432 | 67,532 | 102,451 | 217,316 | 369,940 |

| Colorado | 25,718 | 49,944 | 74,070 | 103,246 | 200,851 | 334,288 |

| Connecticut | 26,764 | 56,555 | 86,346 | 122,359 | 254,404 | 444,303 |

| Delaware | 23,095 | 48,910 | 71,805 | 99,404 | 186,697 | 305,638 |

| Florida | 20,343 | 39,821 | 58,642 | 85,677 | 179,505 | 317,341 |

| Georgia | 19,422 | 39,432 | 59,154 | 87,047 | 177,592 | 302,015 |

| Hawaii | 30,046 | 57,737 | 82,948 | 112,285 | 198,920 | 313,108 |

| Idaho | 21,997 | 41,124 | 58,135 | 80,443 | 152,183 | 252,321 |

| Illinois | 22,282 | 45,800 | 69,212 | 100,354 | 203,217 | 348,399 |

| Indiana | 21,748 | 41,987 | 60,951 | 84,823 | 161,207 | 271,248 |

| Iowa | 23,881 | 46,663 | 66,648 | 90,175 | 168,555 | 279,052 |

| Kansas | 23,726 | 45,529 | 66,031 | 92,639 | 180,459 | 309,887 |

| Kentucky | 18,336 | 38,049 | 56,570 | 81,123 | 161,070 | 279,483 |

| Louisiana | 17,113 | 36,087 | 56,044 | 83,911 | 164,431 | 270,985 |

| Maine | 23,883 | 44,927 | 64,726 | 89,609 | 168,391 | 273,708 |

| Maryland | 27,846 | 57,853 | 85,984 | 120,927 | 230,248 | 377,760 |

| Massachusetts | 25,163 | 55,653 | 86,492 | 121,866 | 236,938 | 396,611 |

| Michigan | 20,854 | 42,173 | 62,596 | 88,877 | 168,920 | 279,121 |

| Minnesota | 27,717 | 52,887 | 76,720 | 104,409 | 200,443 | 341,378 |

| Mississippi | 15,312 | 32,978 | 49,185 | 72,082 | 137,105 | 226,084 |

| Missouri | 22,024 | 42,680 | 61,731 | 86,816 | 169,000 | 287,907 |

| Montana | 21,800 | 43,145 | 63,141 | 87,312 | 167,545 | 282,953 |

| Nebraska | 24,546 | 45,846 | 66,587 | 91,208 | 172,014 | 289,832 |

| Nevada | 21,860 | 41,648 | 59,962 | 85,065 | 164,149 | 275,723 |

| New Hampshire | 30,449 | 58,827 | 83,074 | 112,895 | 206,285 | 323,125 |

| New Jersey | 25,646 | 54,049 | 84,184 | 121,848 | 241,673 | 400,367 |

| New Mexico | 17,064 | 35,379 | 52,747 | 78,997 | 156,728 | 254,096 |

| New York | 21,611 | 45,473 | 72,001 | 106,211 | 234,199 | 430,117 |

| North Carolina | 19,816 | 38,870 | 58,120 | 84,980 | 171,126 | 291,461 |

| North Dakota | 25,905 | 51,630 | 74,835 | 100,575 | 190,473 | 331,841 |

| Ohio | 21,232 | 42,733 | 63,457 | 88,856 | 168,887 | 281,267 |

| Oklahoma | 19,823 | 39,453 | 57,699 | 81,226 | 164,722 | 285,546 |

| Oregon | 23,212 | 44,238 | 65,588 | 93,519 | 181,350 | 298,683 |

| Pennsylvania | 22,638 | 45,955 | 68,133 | 96,112 | 187,074 | 313,265 |

| Rhode Island | 22,102 | 46,800 | 72,714 | 103,301 | 195,205 | 320,433 |

| South Carolina | 18,578 | 38,323 | 56,969 | 81,756 | 160,290 | 271,525 |

| South Dakota | 23,766 | 45,755 | 64,073 | 85,546 | 159,438 | 269,129 |

| Tennessee | 19,430 | 38,815 | 57,474 | 82,649 | 165,437 | 285,446 |

| Texas | 20,807 | 40,582 | 60,865 | 90,009 | 186,280 | 321,326 |

| Utah | 26,373 | 47,492 | 66,123 | 89,859 | 167,921 | 272,594 |

| Vermont | 27,806 | 51,855 | 73,514 | 99,945 | 193,805 | 332,271 |

| Virginia | 24,647 | 50,594 | 76,454 | 110,564 | 217,638 | 352,641 |

| Washington | 25,635 | 49,458 | 73,808 | 104,954 | 201,185 | 329,925 |

| West Virginia | 17,637 | 36,820 | 55,182 | 77,725 | 141,718 | 224,972 |

| Wisconsin | 25,455 | 47,917 | 68,833 | 92,783 | 170,893 | 285,101 |

| Wyoming | 27,426 | 50,847 | 71,256 | 97,227 | 178,985 | 306,021 |

| District of Columbia | 20,110 | 51,859 | 91,541 | 149,555 | 327,959 | 567,911 |

| United States | $22,014 | $44,043 | $66,165 | $95,504 | $191,704 | $325,928 |

Source: CBPP analysis of 2015 American Community Survey (ACS) data Note: ACS income data do not include capital gains. Households were size-adjusted before being sorted into quintiles. Average incomes shown are for a family of four in 2015 dollars

| TABLE 5 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Incomes Grew Much Faster Among Richest 1 Percent of Households Than Rest of Households (Percent Growth Between 1979 and 2013) | ||

| Top 1 Percent | Bottom 99 Percent | |

| Alabama | 83% | 12% |

| Alaska | 85% | -23% |

| Arizona | 73% | -16% |

| Arkansas | 110% | 9% |

| California | 148% | -3% |

| Colorado | 125% | 10% |

| Connecticut | 291% | 15% |

| Delaware | 45% | 3% |

| Florida | 128% | -9% |

| Georgia | 107% | 1% |

| Hawaii | 54% | -9% |

| Idaho | 106% | 3% |

| Illinois | 137% | 1% |

| Indiana | 76% | 0% |

| Iowa | 82% | 18% |

| Kansas | 110% | 16% |

| Kentucky | 60% | -3% |

| Louisiana | 83% | 5% |

| Maine | 96% | 16% |

| Maryland | 122% | 20% |

| Massachusetts | 291% | 38% |

| Michigan | 84% | -18% |

| Minnesota | 129% | 18% |

| Mississippi | 56% | 3% |

| Missouri | 98% | 5% |

| Montana | 102% | 5% |

| Nebraska | 107% | 34% |

| Nevada | 88% | -37% |

| New Hampshire | 145% | 30% |

| New Jersey | 190% | 20% |

| New Mexico | 55% | -9% |

| New York | 272% | 5% |

| North Carolina | 100% | 12% |

| North Dakota | 261% | 44% |

| Ohio | 74% | -4% |

| Oklahoma | 98% | 12% |

| Oregon | 76% | -11% |

| Pennsylvania | 125% | 12% |

| Rhode Island | 112% | 30% |

| South Carolina | 93% | -3% |

| South Dakota | 201% | 29% |

| Tennessee | 111% | 9% |

| Texas | 110% | 4% |

| Utah | 135% | 6% |

| Vermont | 133% | 20% |

| Virginia | 147% | 20% |

| Washington | 142% | -1% |

| West Virginia | 41% | 0% |

| Wisconsin | 120% | 4% |

| Wyoming | 272% | -9% |

| District of Columbia | 155% | 53% |

| United States | 141% | 4% |

Source: EPI analysis of IRS data. Estelle Sommeiller, Mark Price, and Ellis Wazeter, “Income Inequality in the U.S. by state, metropolitan area, and county,” Economic Policy Institute, June 16, 2016

Methodology

Overview:

This analysis uses the latest (2015) household income data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) to measure the post-federal-tax incomes of high-, middle- and low-income households. Estimated Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) payments were added to household income, which is adjusted for payroll taxes and federal income taxes (including the Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit). Note that ACS income does not include capital gains. Average incomes were adjusted for household size before being sorted into quintiles; average incomes shown are for a family of four in 2015 dollars.

Methods:

Income data source: The analysis used the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ multiyear ACS tax model using 2015 income data. Tax parameters are for tax year 2015, incomes are in 2015 dollars, and SNAP imputations are for 2015. Group quarters persons are dropped from the sample.

Tax units: The ACS income data is reported for households, or related and unrelated individuals and families who live together. (“Unrelated” here refers to the person’s relationship with the householder — the person in whose name the housing unit is owned or rented — not with each other.) A household may include one or more tax units. In order to estimate taxes paid by the household, individuals within households are assigned to tax units using the following rules:

Persons related to the householder:

Subfamily IDs are used to group subfamilies into their own tax units.

All other persons related to the householder are grouped into the householder’s tax unit.

Persons unrelated to the householder:

Married unrelated persons are assigned an opposite sex spouse when available.

Unrelated children are assigned to an unrelated parent if available, and, if not, to the householder.

Unrelated couples and parent-child relationships are used to create tax units that consist of unrelated persons.

Unrelated individuals become single person tax units.

Tax filers:

The householder becomes the tax filer for the householder’s tax unit.

For other tax units, whichever spouse is listed first becomes the tax filer.

If there is no spouse, the single parent becomes the tax filer.

Adjusted gross income: The adjusted gross income (AGI) for each tax unit is estimated as follows: Total cash income (PINCP) of the tax filer (and spouse if present) is calculated. Cash assistance (PAP), Social Security (SSP), and Supplemental Security (SSIP) income is subtracted. Half of the self-employment tax (calculated) is subtracted. The taxable portion of Social Security is added.

Refinements:

- For all tax units, the AGI of the spouse is added to the AGI of the tax unit head. This is the tax unit’s AGI.

- The same is true for all other income measures of the tax unit; that is, the tax filer’s incomes, taxes, etc. always include the spouses if present.

- Subfamily tax units with no earnings are reassigned to the householder’s tax unit.

- Adult childless workers (not dependents) who are in the householder’s tax unit with an AGI greater than the personal exemption are treated as their own individual tax unit.

- If the AGI of the householder is below $3,000 and there are adult childless workers being treated as separate tax units in the household, then the adult childless worker with the largest AGI becomes the tax filer for the householder’s tax unit.

- All single unmarried children in a tax unit less than 17 years old are marked as CTC eligible dependents

- All single unmarried children in a tax unit less than 19 years old or less than 24 years old and enrolled in school — or any relative of any age who is disabled and not working (unless that relative is a parent) — are marked as EITC eligible dependents.

- CTC and EITC eligible dependents are summed by tax unit.

Tax liability: The estimated amount of taxes owed is determined based on these tax units:

Filing status: Tax filers are assigned as single, head of household, or married filing jointly, based on tax unit composition.

Itemized deductions: Itemized deductions are estimated for every filer based on the sum of three components:

- Real estate tax deduction is estimated for those with a mortgage based on reported property tax or is otherwise set to 0.

- Mortgage interest deduction is estimated for those with a mortgage based on state averages for each of the ten IRS income classes or is otherwise set to 0.

- All other itemized deductions are estimated based on state averages for each of the ten IRS income classes.

(IRS Statistics of Income data for 2014 by state were used for numbers 2 and 3.)

Standard deduction: The standard deduction is calculated based on tax unit size and composition.

Taxable income is estimated by taking AGI and then subtracting the personal exemption and either the calculated standard deduction or estimated itemized deduction, whichever is larger. Income tax liability is then estimated by applying the income tax brackets to taxable income. Payroll taxes are estimated based on wage and salary earnings. Self-employment payroll taxes are estimated from self-employment earnings. CTC and EITC benefits are calculated based on the number of eligible dependents, AGI, and earnings.

Size-adjusted post-tax, post-transfer (PTPT) household income: The tax units’ incomes are then converted back into household units. For each tax filer, income tax and payroll tax liability is subtracted from total cash income and then the CTC and EITC tax credits are added to yield a post-tax, post-credit income at the tax unit level. Tax unit post-tax, post-credit income is then summed at the household level, along with imputed SNAP benefits.

Average incomes: The final step is the calculation of average household income by quintile. The resulting PTPT household income is then adjusted by dividing by the square root of household size. Persons are then sorted by state and within state by their adjusted household PTPT income into fifths (income quintiles). Negative and zero incomes are left in the sample. The average and maximum of adjusted household PTPT income for each quintile is then calculated. Finally, the average and maximum incomes are adjusted back up to a family of four by multiplying 2 (the square root of 4).

States’ Income and Poverty Gains Even More Widespread in 2015 Than Initially Reported

End Notes

[1] The 4 percent of taxpayers with the highest incomes — those with federal adjusted gross incomes over $200,000 — accounted for 80 percent of all taxable capital gains in 2013, according to IRS data analyzed by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (http://itep.org/itep_reports/2016/08/the-folly-of-state-capital-gains-tax-cuts-1.php#.WC3I9mczVD8).

[2] See Chad Stone et al., “A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated November 7, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/a-guide-to-statistics-on-historical-trends-in-income-inequality.

[3] Estelle Sommeiller, Mark Price, and Ellis Wazeter, “Income Inequality in the U.S. by state, metropolitan area, and county,” Economic Policy Institute, June 16, 2016, http://www.epi.org/publication/income-inequality-in-the-us/.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Isaac Shapiro and Arloc Sherman, “States’ Income and Poverty Gains Even More Widespread in 2015 Than Initially Reported,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 25, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/states-income-and-poverty-gains-even-more-widespread-in-2015-than.

[6] As footnote 1 above explains, the 4 percent of taxpayers with the highest incomes — those with federal adjusted gross incomes over $200,000 — accounted for 80 percent of all taxable capital gains in 2013, according to IRS data analyzed by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (http://itep.org/itep_reports/2016/08/the-folly-of-state-capital-gains-tax-cuts-1.php#.WC3I9mczVD8).

[7] “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 2015, http://www.itepnet.org/whopays.htm.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Elizabeth C. McNichol, “Strategies to Address the State Tax Volatility Problem,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 18, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/strategies-to-address-the-state-tax-volatility-problem.

[10] Michael Mazerov, “State Corporate Tax Shelters and the Need for Combined Reporting,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 26, 2007, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-corporate-tax-shelters-and-the-need-for-combined-reporting.

[11] Michael Mazerov, “State Job Creation Strategies Often Off Base,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 3, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-job-creation-strategies-often-off-base.

[12] For more information on state EITCs, see Policy Basics: State Earned Income Tax Credits, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated June 17, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/policy-basics-state-earned-income-tax-credits.

[13] State EITCs are in effect in California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, Wisconsin, and the District of Columbia.

[14] Michael Leachman and Michael Mazerov, “State Personal Income Tax Cuts: Still a Poor Strategy for Economic Growth,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 14, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-personal-income-tax-cuts-still-a-poor-strategy-for-economic.