- Home

- Remote Identity Proofing: Impacts On Acc...

Remote Identity Proofing: Impacts on Access to Health Insurance

Executive Summary

Most people seeking to apply online for affordable health coverage programs — Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and private health plans through the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Marketplaces — must complete a remote identity proofing (RIDP) process before submitting their application online. RIDP is not an eligibility requirement but rather a way to ensure that online applicants are who they say they are by having them answer a series of personal questions (drawn from their credit files and other sources) that only the actual person could likely answer correctly.

RIDP is intended to protect consumers from unauthorized access to their personal information held by trusted sources like the Social Security Administration, the Internal Revenue Service, and the Department of Homeland Security that is now routinely checked during the online application process, rather than being checked after the application is submitted. However, individuals may encounter a number of challenges during the RIDP process that prevent them from submitting a timely application. As a result, eligible individuals may be less likely to apply for benefits or may experience delays. This report explains the rationale for RIDP, examines the problems it can cause for some applicants, and recommends ways to address them.

Certain groups of individuals are especially likely to experience challenges in completing RIDP. For example:

- People with limited credit histories are unlikely to complete RIDP because, in many cases, the system will lack the information needed to generate questions about them. An estimated 35 million to 54 million American adults either have no credit report or have insufficient information in it to generate a credit score.

- Victims of identity theft who have a fraud alert on their record cannot complete RIDP; they must submit identifying documents for manual review in order to apply online. This process can cause significant delays. In 2014 alone, an estimated 17.6 million Americans were victims of identity theft.

- People with inaccuracies in the data used for RIDP may not be able to complete RIDP. In 2013, the Federal Trade Commission found that one in five consumers had an error on at least one of their credit reports. These errors could interfere with the data matching process needed for RIDP to succeed. They also could prevent an applicant from completing RIDP if his or her answers to the personal questions are accurate but do not match the erroneous information in the system.

- Children under 18 (including emancipated minors) are not permitted to complete the RIDP process and therefore cannot apply online without an adult.

- Certain immigrant parents seeking to apply on behalf of their citizen children are unlikely to complete the RIDP process because they have limited credit histories and may not be able to produce other proof of their identity.

Individuals who experience RIDP-related barriers are disproportionately likely to be uninsured. Without clear pathways to coverage for these groups, including young people and immigrants, achieving the ACA’s coverage goals will be more difficult.

Moreover, RIDP may affect individuals’ access to other human services programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps). Many states opt to have online multi-benefit applications that connect low-income families to more than one program, such as Medicaid and SNAP; many of these applications pre-date the ACA. The RIDP process established for Medicaid and other affordable health coverage programs may conflict with consumer protections under other benefit programs, such as SNAP rules regarding applicants’ right to file an application without delay. As a result, states face challenges in providing online multi-benefit applications that meet all programs’ requirements.

Most federal and state health and human services agencies had little or no experience with RIDP in online applications for public programs prior to the ACA. After two years of ACA implementation, it is appropriate to re-examine the RIDP procedures to identify opportunities for improvement and ensure that the new modernized online application and enrollment services work for all eligible individuals. By re-assessing the risks of unauthorized access to private information in online applications, federal and state agencies can identify the circumstances in which RIDP is needed and consider improvements to minimize barriers to access to coverage. Doing so would promote health insurance among the uninsured.

Recommended improvements to enable more eligible applicants to enroll in affordable health coverage without experiencing RIDP-related barriers include:

- Allowing all applicants to submit online applications before completing RIDP. Online applications could be revised to give applicants who cannot complete RIDP the option to submit applications without having information about their identity checked by federal data sources in “real time” (that is, while they complete the online application). The information in the online application would then be checked against trusted data sources after the application is submitted and the results would be delivered by mail, similar to the paper application process.

- Expanding the data sources used in the RIDP process. To reduce RIDP-related barriers for applicants with limited credit histories, other data sources — such as information held by health and human services programs — could be used to generate questions to be used for RIDP.

- Engaging assisters in the RIDP process. Professional assisters who help people apply for health insurance and subsidies, such as navigators and certified application counselors, could be allowed to submit identity proofing documents on behalf of applicants directly to the reviewing entity, thereby expediting the RIDP process.

- Eliminating unnecessary steps in the process. Certain individuals, such as victims of identity theft and people with insufficient credit histories to generate RIDP questions, are required to try to complete RIDP steps online and by phone even when they clearly cannot complete them. Online applications could instead allow these individuals to upload or mail identity documents immediately, without first having to fail the phone step.

- Expanding the list of acceptable identity documents. Applicants whose identity is not confirmed online or by phone must submit specific identity documents to prove identity. Expanding the list of acceptable documents would reduce the barrier that this documentation step can present.

- Preventing the RIDP process from causing applicants to miss enrollment deadlines. Eligible individuals can enroll in Marketplace coverage only during certain open enrollment periods or after a change in their personal circumstances that allows them a special enrollment period. Application processes could be modified to extend the open and special enrollment periods for those who encounter RIDP-related barriers that delay an eligibility determination.

- Monitoring and publishing RIDP performance data. Establishing metrics for RIDP performance and monitoring, and publishing performance data, would help federal and state agencies improve the RIDP process as needed.

- Reassessing appropriate security approaches given current knowledge about risks. After two years of ACA implementation, it is appropriate for federal agencies to reassess the risks of unauthorized access to personal information during the online application process and to adopt technical solutions that may be needed. This reassessment would allow the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to protect consumers' information while promoting access to health coverage for young adults and others experiencing barriers to applying online.

Streamlined access to health insurance and protection of personal information are both critical priorities. Neither should come at the other’s expense. The steps identified in this paper can help avoid RIDP-related barriers that prevent or delay eligible consumers from obtaining health insurance.

Box 1: Work Support Strategies

This report was written in coordination with the Work Support Strategies Project. Work Support Strategies (WSS) is a multi-year, multi-state initiative to help low-income families get and keep the package of work supports for which they are eligible. With philanthropic support, WSS has worked directly with Colorado, Idaho, Illinois, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and South Carolina since 2011. Through grants and expert technical assistance, WSS helps states reform and align the systems delivering work support programs intended to increase families’ well-being and stability — particularly SNAP, Medicaid and CHIP, and child care assistance through the Child Care and Development Block Grant. Through WSS, states seek to streamline and integrate service delivery, use 21st century technology, and apply innovative business processes to improve administrative efficiency and reduce burdens on states and working families with the overall goal of increasing participation and retention to support work and well-being. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities coordinates the technical assistance for the project in partnership with CLASP, which also provides project management, and the Urban Institute, which is conducting the evaluation. Our work in this effort helped to inform this paper.

For more information about WSS, see: http://www.clasp.org/wss.

Background

The Affordable Care Act calls for streamlined eligibility processes for affordable health coverage programs, including Medicaid, CHIP, and qualified health plans offered through federal and state Marketplaces. This streamlining includes increased availability of online services, including online applications, online Marketplace health plan selection, and the use of electronic data sources to verify certain eligibility factors and deliver eligibility results in “real time” — that is, during the online application process. These enhancements are intended to enable individuals to apply for benefits at a time, place, and pace of their choosing and to promote timely access to benefits.

An array of security and privacy measures protect consumer information under these streamlined eligibility and enrollment processes. One aspect of the overall security and privacy plan that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has built into the HealthCare.gov online application and made available to state-based Marketplaces (SBMs) and state Medicaid and CHIP agencies for their online applications is remote identity proofing (RIDP).[1] RIDP is not an eligibility requirement but rather a process to protect consumer information by confirming that online users are who they say they are, based on their answers to a series of personal questions that only the actual consumer is likely to answer correctly. These questions are largely drawn from information in the consumer’s credit history.

HHS contracts with Experian, one of the three major credit reporting agencies, to support RIDP for HealthCare.gov users. HHS also makes the Experian RIDP service available to SBMs and state Medicaid and CHIP agencies through the federal data services hub, a mechanism for state and federal agencies to exchange information for administering the ACA.[2] States have the option of using this service, augmenting it with additional identity proofing processes, or using different processes that comply with privacy and security standards.[3] Most states use the RIDP service provided through the federal data services hub.

Most applicants can complete identity proofing online or on the phone, in real time. However, a significant number of applicants are unable to complete this process online in real time as intended because there is not enough information in their credit history to generate the questions necessary to satisfy the RIDP process. They must go through one or more extra steps offline to prove their identity before submitting an online application for health coverage programs. (This paper uses the term “applicants” to refer to all consumers seeking information about or access to affordable health coverage programs through an online application such as HealthCare.gov, whether or not they actually complete and submit an application. These individuals may include people seeking health insurance for themselves and/or for others, such as their children.)

Rationale for Remote Identity Proofing

When federal agencies share personal information, they are required to adopt consumer protections to keep it private and secure “commensurate with the risk and magnitude of harm that could result from the loss, misuse, or unauthorized access to or modification of such information.”[4] For internet transactions, federal agencies must specifically assess the potential for and likelihood of harm resulting from sharing information with someone whose identity has not been confirmed. The greater the risk, the greater the level of assurance needed that the person seeking information access is who he or she claims to be. Federal agencies must identify the lowest level of assurance that will protect against all of the identified risks and then implement an appropriate technical solution to achieve that level of assurance, based on National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) guidelines.[5]

In implementing online services for Medicaid, CHIP, and qualified health plans offered through federal and state Marketplaces under the ACA, HHS determined that RIDP was necessary to achieve the level of assurance required to protect consumers’ information.[6] The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service’s (CMS) guidance to states regarding RIDP indicates the determination was based primarily on the interaction between online applications for benefits and the federal data services hub.[7] When people apply for benefits online, the application system accesses the hub in real time (i.e., during the same session in which the applicant enters and submits application data) in order to compare data provided by the applicant to personal data held by the agencies connected to the hub, including the Social Security Administration (SSA), Internal Revenue Service, and Department of Homeland Security.[8] No data held by the agencies are shown to the online applicant, but the applicant may learn that there are inconsistencies between what he or she entered and the data held by the other agencies or may infer that the information he or she entered was verified.[9]

The following examples of the HealthCare.gov process illustrate how government information held by other agencies might be shared with applicants indirectly, indicating the risks of unauthorized access to personal information if an online applicant is not who he or she claims to be.

- When an applicant using HealthCare.gov enters a Social Security number (SSN), HealthCare.gov sends that number and other identifying information about the applicant to the hub, which in turn forwards the information to SSA’s systems for comparison against SSA data in real time. The SSA’s systems send the results of the comparison back to the hub, which forwards the results to HealthCare.gov. If there is an inconsistency, the applicant is given a limited number of attempts to re-enter the SSN. At no point does the applicant see any information held by the SSA, but if the applicant is prompted to re-enter the SSN he or she can infer that there was an inconsistency.

- Similarly, when HealthCare.gov provides eligibility results to an applicant, the results may indicate that he or she needs to provide documentation of certain eligibility factors, such as income or citizenship. The applicant does not see any information held by the other agencies but may infer from the results that the other agencies either have insufficient data to verify the information in the application or that the information is not close enough to what other federal agencies have on file.

HHS determined that RIDP was required as part of an overall security plan to protect consumers against harm if personal information were disclosed to someone whose identity has not been confirmed.[10]

Identity Proofing by the Federally Facilitated Marketplace

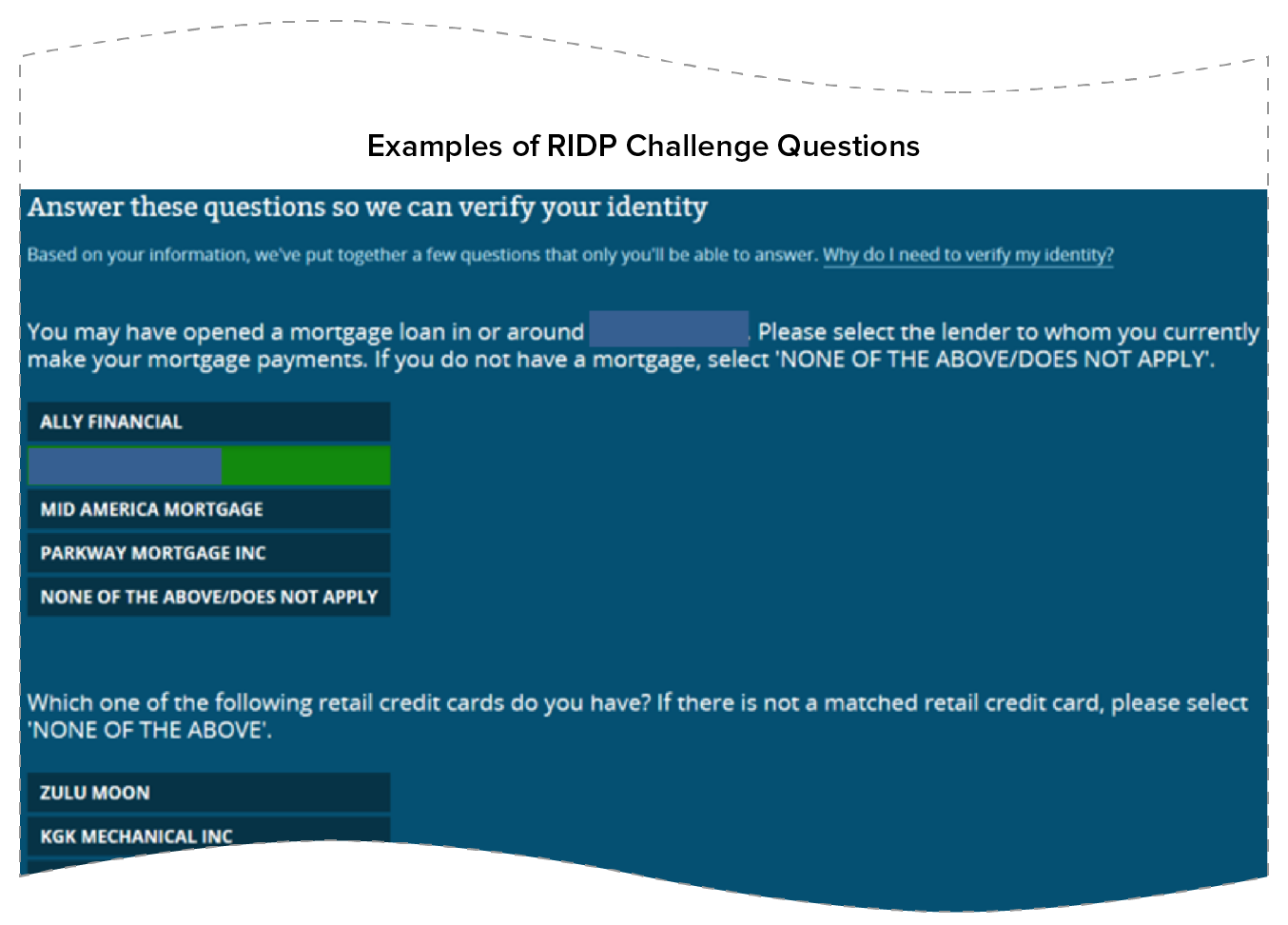

RIDP is a process for confirming the identity of an online user without requiring in-person interaction. Typically, applicants are asked a series of individually tailored questions generated automatically by the online system, based on data from credit bureaus and other sources. These knowledge-based questions, also known as “out of wallet” questions, are likely to be answered correctly only by the actual consumer. For example, the consumer might be asked to select the name of his or her mortgage lender or the range of his or her auto loan payment. Similar processes are sometimes used in other online transactions like opening up a new bank account. If the applicant successfully answers the questions, the RIDP process is complete; the system has a reasonable assurance that the applicant is who he or she claims to be and allows the applicant to move forward accordingly.

The RIDP process used by the federally facilitated Marketplace (FFM) for people applying for Medicaid, CHIP, and qualified health plans and subsidies through HealthCare.gov is described in greater detail below. State-based Marketplaces and state Medicaid and CHIP agencies are permitted to use the same RIDP service through the FFM’s RIDP contractor, Experian. Most have chosen to do so.

RIDP is just one component of the ACA privacy and security plan for protecting consumers against unauthorized access to their information held by government agencies. For example, CMS encrypts electronic data, retains minimal data from the federal data services hub, and has role-based security controls to limit employees’ and contractors’ access to information only as needed to perform their duties.[11] Unlike other privacy and security measures, however, RIDP uniquely affects individuals’ access to benefits under the ACA.

It is important to note that while RIDP can pose a barrier to access, identity proofing is not an eligibility requirement. RIDP focuses on confirming the applicant’s identity in order to gain a level of assurance that the applicant is who he or she claims to be; it provides no indication of whether the applicant is eligible for benefits. Many eligibility factors such as citizenship, immigration status, and income must be verified by submitting proof and/or by providing key document numbers that are verified against data held by government agencies and other trusted sources.

Beginning Online

Applicants using HealthCare.gov to apply for coverage online are first instructed to set up an account. They are required to provide an email address, create a password, and select key questions and answers that can be used if they need to re-set their passwords. HealthCare.gov sends applicants a link to the email address provided; the applicant must use that link to verify the email address and access the new account.

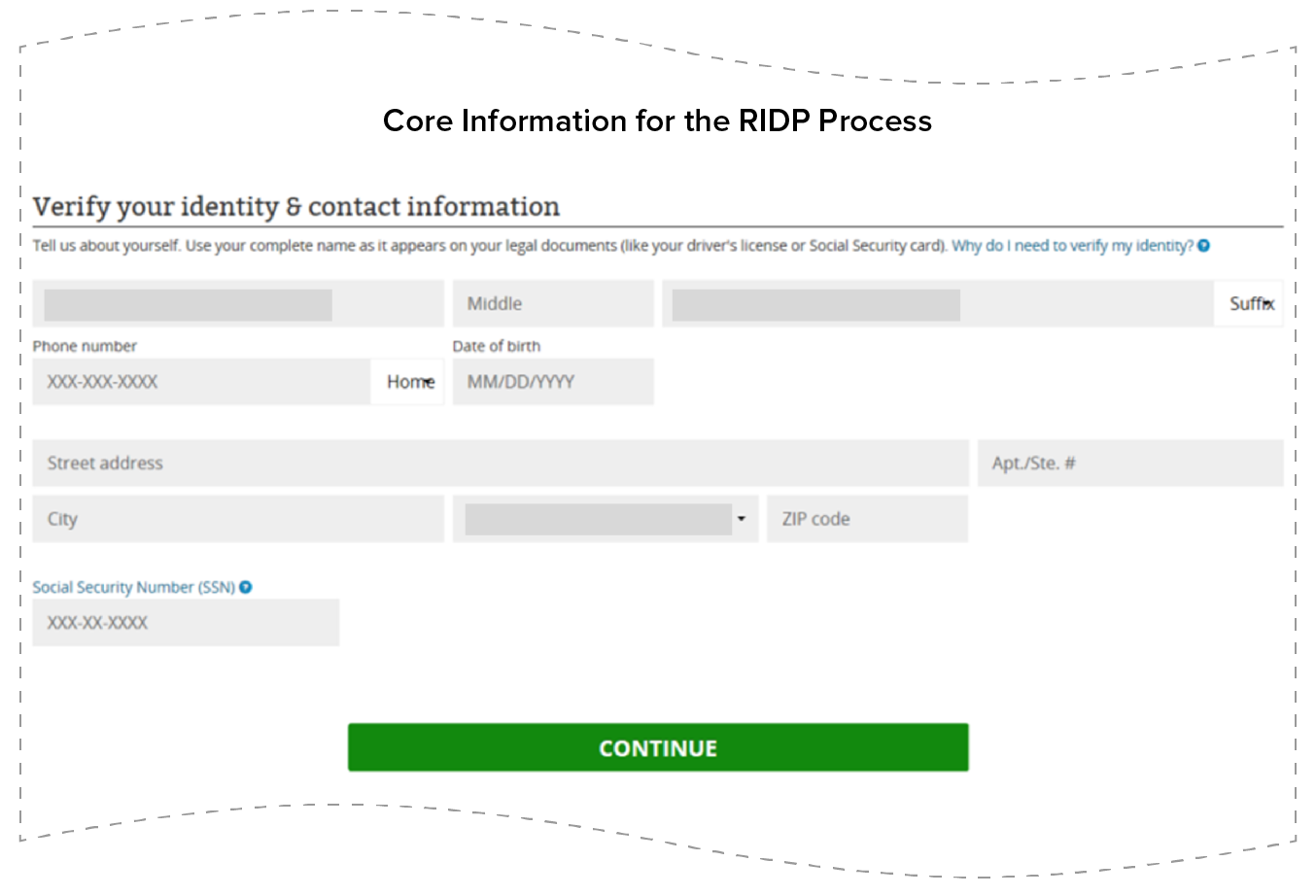

Shortly after setting up their accounts, applicants begin the RIDP process by providing core information about the application filer (i.e., the person completing the online form), including name, address, phone number, and date of birth. The application filer’s SSN may also be provided but is not required (see Figure 1). HealthCare.gov then sends the core information to Experian.

Experian matches the core information provided about the application filer against information in its extensive database, which includes (but is not limited to) information related to credit history.[12] If Experian cannot find matching data, it prompts HealthCare.gov to ask the applicant to re-enter the core information to correct for any data entry errors. If Experian finds a match, it uses additional data about the application filer from its database to generate challenge questions in real time. Challenge questions vary greatly and depend on the specific information Experian has for the individual. For example, questions may ask about past addresses, name of a mortgage company, names of schools attended, names of active credit cards, or vehicles owned (see Figure 2).

If Experian has sufficient data about the application filer to create challenge questions, the questions are sent to HealthCare.gov and presented to the applicant. If the applicant successfully answers the questions, he or she has passed RIDP and can complete and submit the application online and get an eligibility determination.

Continuing by Phone

Application filers who do not pass RIDP at this point — i.e., those who do not answer the challenge questions to the satisfaction of Experian or who never receive challenge questions because Experian lacks enough information to create questions — are directed to call the Experian Help Desk. The Experian Help Desk will then try to ask the applicant challenge questions over the telephone, if there is sufficient data to generate challenge questions.

Application filers who pass the RIDP process over the phone are instructed to log into their HealthCare.gov account (if not already logged on) and resume the application. Application filers may be able to do this immediately or may have to wait up to 48 hours until the system is ready for them to resume. Once the system is ready, applicants return to the same screen where they were instructed to contact the Experian Help Desk. A button on this screen allows the applicant to indicate that he or she called the Experian Help Desk. When the application filer clicks that button, he or she will be prompted to re-enter the core information (name, address, phone number, date of birth), with one opportunity to retry. The core information will again be matched against Experian’s systems. If the core information is correctly entered and the match indicates that the applicant has already passed the RIDP process through the Experian Help Desk, the application filer can proceed with the online application without answering additional challenge questions beyond those already answered through the Experian Help Desk.

Submitting Documents as Needed

If an application filer is unable to answer the challenge questions over the phone or if no challenge questions could be generated, Experian instructs the individual to log back into his or her HealthCare.gov account if not already logged on, as described above. When the application filer logs in and clicks the button to indicate that he or she has called the Experian Help Desk, the matching process with Experian’s systems will indicate that he or she was not able to pass the RIDP process through the Experian Help Desk and will prompt the applicant to provide documents that can prove his or her identity. Application filers will be given instructions on how to upload the necessary documents online or submit them by mail. The majority of consumers who turn in documents to prove their identity mail them rather than uploading them electronically. Until the required documents are submitted and processed, application filers cannot submit an online application. Figure 3 lists the acceptable identity documents.

| FIGURE 3 | |

|---|---|

| Acceptable Identity Proofing Documents | |

| Submit one of these: | Alternatively, submit two of these: |

|

|

Once the documents are received, a CMS contractor reviews them to see if they are sufficient to authenticate identity. If they are, the contractor updates the applicant’s HealthCare.gov account with this status, sends a notice to the applicant by mail, and calls the applicant to encourage him or her to revisit HealthCare.gov.[13] When the application filer logs back into his or her HealthCare.gov account, he or she will have full access to the account and will be able to complete steps such as submitting an application online, using plan comparison tools, reviewing notices about his or her eligibility in the personal account, reporting changes in income or other personal circumstances, and renewing coverage the following year. So long as the applicant continues to use the same HealthCare.gov account, he or she will not be required to repeat the RIDP process.

Application filers who do not successfully complete the identity proofing process or are waiting for the process to be completed can continue with the online application and provide all of the requested information. However, HealthCare.gov does not allow applicants to submit an application online until the identity proofing process is completed successfully. This differs from traditional health and human services applications, which allow consumers to submit applications even if they are incomplete in order to preserve the effective date of benefits for use once the application process is complete.

RIDP Impedes Access to Health Insurance for Some Applicants

Precise data on the success rate of the RIDP process are not available. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), about 78 percent of people who attempted the Experian RIDP process through HealthCare.gov or a state using Experian’s service through the federal data services hub completed it successfully.[14] It is not clear whether they did so without having to call the Experian Help Desk or submitting identity documents, or whether some of them needed to take those additional steps. It also is not clear what happened to the remaining 22 percent of applicants. Experian officials noted that in “many cases” Experian was not able to generate challenge questions or the applicant did not respond to the questions that were generated.[15] None of these individuals would have been able to submit an online application unless they completed identity proofing over the phone or by submitting documents.

Growing evidence suggests that RIDP is a significant challenge for some applicants. Much of this evidence comes from professional assisters who help people as they apply for health insurance and subsidies, including navigators, certified application counselors, and federally qualified health center employees. In a 2015 survey, 11 percent of assisters said that all or most of their clients sought help proving identity in ways unrelated to citizenship; this figure was a significant increase from the previous year’s 7 percent.[16] In a separate 2015 survey of assisters who work with immigrant households in FFM states, about 40 percent indicated that identity proofing is often or almost always a problem when applying for coverage online. About 53 percent of assisters in this survey listed improving the identity proofing process as one of the top three ways the FFM could improve the application process for immigrant applicants and individuals in immigrant families.[17]

Individuals seeking to apply online for ACA coverage and subsidies may encounter a number of challenges during the RIDP process. As a result, eligible individuals may be less likely to apply for benefits or may experience delays in the online application process, meaning their health coverage will be delayed or denied and they may have to forgo needed medical treatment. Some consumers who experience RIDP challenges will seek help from an assister; others will apply by mail or phone. Examples of challenges applicants may face in the RIDP process include:

- RIDP will never succeed for certain types of applicants. Experian will not produce RIDP challenge questions when there is a fraud alert in the records matching the core information. A fraud alert is placed in a credit file when someone has been a victim of identity theft. An estimated 17.6 million Americans were victims of identity theft in 2014.[18] RIDP limitations in the case of a fraud alert are not clearly indicated at the beginning of the RIDP process, so applicants who have been victims of identity theft may go through the RIDP process unnecessarily and experience avoidable delays. In addition, children under 18 (including emancipated minors) are not permitted to complete the RIDP process and therefore cannot apply online without an adult.[19]

- RIDP is unlikely to be successful for people with limited credit histories. Experian officials have indicated that the 78 percent success rate of the RIDP process they use under the ACA is marginally lower than the general success rate for identity-proofing services they provide, likely because the Marketplace applicant population is less likely to have an “electronic footprint” upon which identity proofing is based.[20] Because Experian draws heavily upon credit report data to produce the challenge questions, it is unlikely to be able to generate challenge questions for people with limited or no credit histories. An estimated 35 million to 54 million American adults either have no credit report or have insufficient information in it to generate a credit score;[21] they include disproportionate numbers of young adults, immigrants, and recently divorced or widowed individuals with limited credit histories.[22] Such individuals are unlikely to be able to complete the RIDP process online or through the Experian Help Desk.

- The Experian Help Desk’s RIDP success rate is low. Experian officials report receiving about 560,000 calls to the Experian Help Desk from October 2013 to April 1, 2015, after applicants did not pass the online RIDP process. In about 35 percent of those cases, identity could be verified.[23] All applicants who do not pass the online RIDP process on HealthCare.gov are referred to the Experian Help Desk, even if Experian had insufficient data to generate challenge questions. It is unclear whether the Experian Help Desk draws from a different set of data sources than the Experian online process and therefore is likely to resolve RIDP challenges for applicants in this situation. If it does not draw on more data or from different data sources to generate questions, then applicants who did not get challenge questions online are unlikely to get them through the Experian Help Desk and will not be able to pass the RIDP process over the phone.

- Some applicants may experience delays after calling the Experian Help Desk. According to HHS guidance for assisters, applicants may need to wait up to 48 hours after calling the Experian Help Desk before logging back into their accounts and proceeding with next steps.[24] It is not clear whether the waiting period is technically necessary. Nevertheless, assisters relying on this guidance may ask their clients to schedule a return visit to the assister to complete the application once this waiting period has passed. This return visit may not happen right away due to scheduling challenges for applicants who may have to alter work and/or child care plans. If the waiting period is not technically necessary, the guidance to assisters is misleading and may unnecessarily prevent or delay applicants from receiving needed assistance.

- Submitting identity documents lengthens the application process. CMS reports a nearly 100 percent identity proofing success rate for those who submit documents, with most documents reviewed and proofing complete within 48 hours of document receipt. However, CMS receives nearly 10 times more identity documents by mail than uploaded online through HealthCare.gov, which adds to processing times and administrative burdens because documents must be carefully associated with the correct case file.[25] It is not clear why applicants prefer mailing documents, but reasons may include lack of access to scanning equipment and unfamiliarity with the uploading process. In addition, applicants may not have, or may require additional time and expense to obtain, the specific documents required for identity proofing.[26] It is unclear how many applicants never submit identity-proofing documents. Finally, consumers completing the process close to the end of an enrollment period face the risk that they will not be cleared to submit the application online before the period ends.

- RIDP imposes additional challenges for certain immigrant parents seeking to apply on behalf of their citizen children. The RIDP process being used by the FFM and many state agencies may be inconsistent with long-standing federal program requirements intended to reduce administrative barriers that inappropriately discourage eligible individuals in immigrant families, such as children, from seeking needed assistance.[27] Some adults do not have an “eligible immigration status” and thus are not applying for benefits for themselves, but are seeking benefits for their children or other family members. Many of these immigrants are unlikely to be able to pass the RIDP process online or over the phone due to limitations in the data sources used to generate RIDP challenge questions. In these circumstances, they are asked to provide proof of their identity in order to submit an application on behalf of their eligible family members. Many of these individuals will not have proof of their identity or the ability to get such proof and may abandon the application process altogether for their eligible family members.

- Inaccuracies in the data used for identity proofing contribute to failures. In 2013, the Federal Trade Commission found that one in five consumers had an error on at least one of their credit reports.[28] These errors may include inaccuracies or inconsistencies in name, address, SSN, or other information; mingling of data related to different people of the same or similar names; outdated information that does not reflect a recent move or name change (e.g., due to marriage); or information resulting from identity theft. These errors may create mismatches between the core information provided by the applicant and the information held by Experian, which may in turn result in insufficient data to generate challenge questions or the generation of challenge questions that are not relevant to the applicant and are therefore not a reasonable basis for identity proofing. Applicants’ access to health insurance may be delayed while they attempt to correct these errors or overcome related RIDP failures.

- Applicants who fail online RIDP and phone RIDP and cannot provide documents to prove their identities will not have access to important online features to help them enroll and retain coverage. They may be able to get comparison information online using the HealthCare.gov or SBM window shopping features, but the information may not be completely accurate because it will be based on simple screening questions rather than the applicant’s actual eligibility. In addition, they will not be able to select a plan online, but must make their selection by telephone. Comparing plans over the phone is extremely difficult and time consuming, as call center operators must read all plan specifics. As a result, these applicants may not get sufficient information to make the best plan choice. Similar challenges occur once enrollment is complete, as enrollees who have not completed RIDP will not be able to access online account features such as reporting changes in their income and other circumstances that may affect their eligibility; nor will they be able to complete the renewal process and change health plans online during the next open enrollment period. As a result, they may find it more difficult to retain coverage that meets their needs over time.

Identity Proofing by States Offers Promising Practices

CMS requires state-based Marketplaces and state Medicaid and CHIP agencies to perform identity proofing as part of the online application process. Most states rely on the Experian identity proofing service provided by HHS through the federal data services hub. However, some states using this service have adopted complementary processes to help applicants avoid some of the challenges described above. For example, New York and California have state-based Marketplaces and rely on the federal RIDP service but have implemented variations from the FFM process.

- New York’s process varies from the FFM process in at least two ways. First, New York has expanded the data sources it uses for identity proofing. When the Experian RIDP process is not successful, New York uses state DMV and Medicaid records to attempt to confirm an applicant’s identity in real time. Second, New York has found ways to engage assisters in the identity proofing process. It established a dedicated unit within its call center that assisters can contact if their clients can’t pass the online RIDP process. All assisters can fax identity documents to this call center, where they are manually processed on an accelerated basis, thus speeding completion of the identity proofing process and allowing assisters to help their clients continue applying online. Up to 15,000 cases per month go through this process. In addition, navigators in New York — a subset of assisters who have contracts with the state and are highly trained — can call the dedicated unit at the call center to request an override of the RIDP process in real time, on the condition that the navigator has reviewed the necessary identity documents and will upload them along with the applicant’s submitted application.[29]

- California has also incorporated assisters into the identity proofing process. Assisters can visually verify and upload identity documents as an alternative to helping applicants through the federal RIDP process. An assister who is working with a client and registered with the state can log onto the assister’s online account in the state system and access the assister version of the online application. This version provides an option for the assister to attest that he or she has visually verified the applicant’s identity and upload satisfactory identity documents. The assister can then help the client complete and submit the online application without the client having to go through the federal RIDP process.[30]

Identity Proofing in Other Federal Programs Does Not Present the Same Access Barriers

Federal programs have differing approaches for confirming online users’ identities. Online services provided by the Department of Education’s Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and the Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) eBenefits system illustrate some of the options. In both cases, individuals can access basic online services, such as completing and submitting an application for benefits, without completing identity proofing but must confirm their identity before accessing personal information and using more advanced online tools.

- The FAFSA is an application for federal financial aid to help students pay for higher education. Individuals can complete the FAFSA online. When they do so, they have the option to obtain a user-created username and password called the Federal Student Aid ID (FSA ID). Individuals can complete and submit the FAFSA online without an FSA ID, but they must have an FSA ID in order to access or correct their information online or to pre-fill a new FAFSA using information already provided on a prior year’s FAFSA.[31] An FSA ID is also required to use the IRS Data Retrieval Tool, which allows applicants to obtain the FAFSA-required tax filing information directly from the IRS and import it into the FAFSA.[32] To obtain an FSA ID, individuals must provide a username, password, and email address and enter personal information such as name, date of birth, SSN, and address. Once the ID is created, it can be immediately used to electronically sign a new FAFSA. In order to complete a renewal, access previously entered information, or access other FSA websites such as StudentLoans.gov, however, the name, date of birth, and SSN associated with the FSA ID must be verified by the Social Security Administration. This verification process takes 1-3 days.[33]

- The VA eBenefits system is a web portal that allows people to research, access, and manage their VA and military benefits. Individuals must have an account to use eBenefits; there are two types of accounts. A Basic eBenefits Account allows users to apply for some benefits online and access personal information they have entered. A Premium eBenefits Account allows users to access personal information about themselves held in VA and Department of Defense systems and use the full range of eBenefits features, such as checking the status of claims, messaging physicians, and ordering medical supplies. To get a Premium eBenefits Account, users must have their identity verified online or by phone by correctly providing information from military accounts or identification cards, or by providing identification in person at specified locations.[34]

Implications for Other Health and Human Services Programs

The ACA requires a single streamlined application for Medicaid, CHIP, and health plans through the ACA Marketplaces. While the ACA does not expressly require the application to include SNAP and other non-health programs,[35] many states have online multi-benefit applications that give low-income families a convenient one-stop connection to multiple programs, such as Medicaid and SNAP; many of these applications pre-date the ACA. Federal agencies are encouraging states to move toward these kinds of integrated approaches.[36] In doing so, however, states must comply with the rules of each program.

Multi-benefit online applications can significantly reduce burden and duplication of work for families and states because much of the information that states need to establish eligibility, such as details about family members and their incomes, is common across the programs. Furthermore, a large share of individuals who qualify for one program also qualify for others. SNAP, for example, is generally available to households with gross income below 130 percent of the federal poverty line, while Medicaid now covers individuals in families up to 138 percent of the federal poverty line in states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA.

Complying with all program rules within one multi-benefit application can be challenging for states. For example, SNAP and Medicaid have long-standing consumer protections that preserve the date of application and allow people to submit incomplete applications. This is because eligible individuals are often at risk of hunger and/or experiencing a medical need when they start the application process and may not have immediate access to all of the information needed to complete the application. The ability to submit an incomplete application protects the applicant’s date of eligibility, which is the date from which benefits are calculated. Once an application is submitted, SNAP applicants have 30 days to provide all necessary information, including verification of their circumstances and proof of their identity. If applicants had to wait until they had every piece of information requested in the application before submitting it, their date of eligibility would be delayed and they could miss out on benefits for which they are eligible. The Food and Nutrition Services (FNS), the federal SNAP agency, has clarified that this ability to submit an incomplete application is a consumer protection that must be provided in all modes of application, including online.[37]

A state seeking to establish or maintain an online multi-benefit application that includes Medicaid and SNAP must reconcile these long-standing SNAP requirements with the new RIDP practices used by Medicaid agencies. States have developed different approaches to meet this challenge.

- Some states that use the federal RIDP service for their Medicaid online application have moved away from multi-benefit applications, at least temporarily. They have a single streamlined online application for health programs and one or more separate online applications for SNAP, TANF, and other social service programs. RIDP is required only for the online health application. Having separate, duplicative applications for these programs is more burdensome for states and applicants alike and increases the risk that people who qualify for multiple programs will not receive all the benefits for which they qualify.

- Other states have opted to use the federal RIDP service as part of their multi-benefit online application but use it only for applicants for health benefits. When someone applies only for SNAP and/or TANF, the state uses an alternative application flow that does not include RIDP, consistent with those programs’ requirements. This approach requires significant IT complexity but preserves many of the efficiencies for applicants and states that multi-benefit applications offer. However, states taking this approach must be mindful of the potential barriers to SNAP or TANF that RIDP may present when people opt to apply jointly for these programs and health programs. Specifically, they must adopt approaches that allow people to submit applications for those programs without delay, regardless of RIDP results.

- Other states that are committed to a multi-benefit application approach have opted not to use the Experian RIDP service offered by CMS through the federal data services hub. Instead, they have created their own standards and methods for identity proofing, including using different data sources for generating identity proofing challenge questions. These data sources may be of greater relevance to the populations served by SNAP and TANF, mitigating some of the risks of RIDP to those applicants. Nevertheless, careful monitoring of barriers to access is warranted.

Recommendations

Because individuals likely to experience RIDP-related barriers are also disproportionately likely to be uninsured, RIDP may weaken ACA outreach and enrollment efforts. For example, the uninsured rate for young adults in 2014 ranged from 17.7 percent at age 19 to 25.1 percent at age 26, the highest uninsured rate for any age.[38] People with lower household income and non-citizens had lower health insurance rates than people with higher household income and citizens.[39] As federal and state agencies seek to increase health insurance rates by reaching out to those who are likely eligible but uninsured, they must also work to eliminate barriers, including those related to RIDP, that may prevent or delay these individuals from applying for and enrolling in coverage. Ensuring that all people seeking health insurance have equal access to all means of applying, including applying online, will help to accomplish the ACA’s coverage goals.

Moreover, streamlined eligibility and enrollment processes under the ACA, including practices used by the FFM, are establishing a direction for all online applications for benefits, including multi-benefit applications. Therefore, it is increasingly important to examine the impacts of those practices on eligible individuals’ access to health insurance and other essential human service programs. RIDP is not an eligibility requirement for health and human services programs, yet it has become a barrier to enrollment for individuals seeking to apply for programs online. With more than two years of ACA RIDP experience gained, this is an opportune time to revisit implementation approaches with an eye to ensuring that online applications provide access to benefits for all eligible individuals.

Allow All Applicants to Submit Online Applications

A well-designed online application follows federal and state program rules and offers applicants potential advantages. For example, dynamic online applications can be less confusing and easier to navigate than paper applications and can reduce or eliminate unnecessary data collection. These advantages are not currently available to all applicants due to RIDP. If RIDP continues to be deemed necessary under NIST standards, CMS can give individuals the option of an alternative online application that retains many of the advantages of an online application but does not share information with the applicant in ways that invoke the need for RIDP.

CMS already has such an alternative online application process at least partially in use on HealthCare.gov. Applicants who have attempted but not yet completed RIDP have the option to complete — but not submit — an online application. This approach allows applicants to make progress while awaiting contact with the Experian Help Desk (which is not open at all hours) or processing of documents they have submitted. This version of the online application simply collects information from the applicant and does not display any information to the applicant that is derived from the federal data sources or other third-party sources. For example, applicants are not prompted to re-enter an SSN based on a failure to find a matching SSN in the SSA database. Without such information sharing, there is no risk of unauthorized disclosure to an online user who is not who he or she claims to be.

Building on this approach, CMS could allow applicants to submit this existing alternative online application once completed and not display the eligibility results to the applicant in real time. Instead, this alternative online application could be processed and results conveyed to the applicant in the same manner as paper applications. CMS could either make this alternative online application process available to all applicants or continue to make it available only to applicants who have attempted but not yet completed RIDP. In either case, applicants who would like the advantages of ongoing online services, such as the ability to see the status of their application, amend their application, report changes, manage their benefits (e.g., change health plans after reporting a change in circumstances that affects their eligibility for subsidies), or streamline the renewal process using pre-populated data, would need to complete the identity proofing process successfully. This approach is akin to the process the Department of Education uses for financial aid (described above).

Improve the Identity Proofing Process

There are a number of steps the FFM, state-based Marketplaces, and state Medicaid and CHIP agencies could take to reduce or eliminate the barriers applicants face in the RIDP process, without compromising security and privacy protections. Potential improvements include:

- Expand the data sources used in the RIDP process. In many cases in which applicants cannot successfully complete identity proofing online or through the Experian Help Desk, the failure results from Experian’s inability to generate RIDP challenge questions due to a lack of data. States such as New York have addressed this challenge by using alternative data sources, such as data from state programs, for identity proofing. Expanding the data sources that are available to complete identity proofing in real time, rather than referring applicants to the Experian Help Desk, would reduce RIDP-related delays while promoting successful identity proofing.

- Engage assisters in the RIDP process. Applicants who experience problems with identity proofing often turn to assisters for help, but assisters generally have no options other than helping these individuals file an application by phone or on paper. However, states like California and New York have found ways to incorporate assisters into the identity proofing process to improve success rates and retain the advantages of online applications. Building on these states’ examples, CMS and states could allow assisters to submit identity proofing documents on behalf of applicants online or directly to the reviewing entity specified by CMS or the state, thereby allowing applicants to accelerate or bypass the online RIDP process.

- Eliminate unnecessary steps in the process. All online applicants are required to go through the online RIDP process and may be required to call the Experian Help Desk, even in the circumstances described above where it is clear that these steps cannot succeed. The following approaches would help applicants avoid unnecessary delays: First, federal and state agencies can provide clear instruction at the beginning of the RIDP process to help applicants understand what to expect and provide alternative options for those likely to experience challenges, such as emancipated minors and people with fraud alerts on their credit reports. Second, in the event no RIDP challenge questions can be generated online for an applicant, federal and state agencies can give the applicant an opportunity to upload or mail identity documents immediately without first having to call the Experian Help Desk. Third, federal and state agencies can direct applicants who experience RIDP-related delays to an assister (if there is a mechanism for assisters to accelerate or bypass RIDP as described above) and/or to a call center to submit an application by phone.

- Allow individuals to complete as much of the online application process as possible while identity proofing is pending. As described above, the HealthCare.gov application allows individuals who have not yet successfully completed the RIDP process to fill out all data fields in the online application but not submit it. Some state online applications, however, do not allow individuals to move forward with the online application process at all until the RIDP process is completed successfully. This approach may create even greater access barriers. Introducing the RIDP process as late in the application process as possible would allow them to make more progress toward a complete application. At a minimum, all states can follow the HealthCare.gov approach of allowing applicants to fill out all application fields but not submit an online application while RIDP is pending. Another approach would be to let consumers fill out all application fields first and then introduce the RIDP process right before the consumer submits the application. Consumers who pass RIDP could have their eligibility factors checked in real time and get an immediate eligibility determination. Consumers who don’t pass RIDP could upload documents to prove their identity at that time. Furthermore, all states and the FFM could ensure that when application filers submit documents to prove their citizenship or immigration status, those documents are also used to satisfy the identity proofing requirement whenever possible.

- Expand the list of acceptable identity documents. Applicants whose identity is not confirmed through the online RIDP process or the Experian Help Desk must submit specific identity documents. Expanding the list of acceptable documents would reduce the barrier this documentation step can present. For example, when an applicant cannot produce an identity-verifying document (e.g., in the case of a homeless person), California will accept an affidavit signed by a third party under penalty of perjury.[40] Other documents that could be considered include notices from a public benefits agency or a combination of documents such as foreign driver’s licenses or federal electoral photo cards, official school or college transcripts that include the applicant’s date of birth, or a signed lease agreement with an address that conforms to the address shown on a photo ID.[41]

- Prevent applicants from missing enrollment deadlines due to the RIDP process. As described above, there are many ways in which the RIDP process can prevent or delay applicants from submitting an application, receiving an eligibility result, and enrolling in coverage. Because eligible individuals can only enroll in exchange coverage during certain open enrollment periods or when they experience a change that allows them a special enrollment period, these RIDP-related barriers may cause applicants to miss their enrollment windows. Federal and state agencies can avoid this result by extending the open and special enrollment periods for those who encounter RIDP-related barriers that delay an eligibility determination.

- Monitor and publish RIDP performance data. Much information about the RIDP process is unavailable, such as success rates, failure rates, reasons for failures, or variations in performance over time, by step in the process, by state, or by applicant characteristics. The FFM and state exchanges can promote improvements in system performance, security, and access by establishing metrics for RIDP performance, monitoring and publishing the data, and making evidence-based improvements as needed.[42]

Reassess Appropriate Security Approaches Given Current Knowledge About Risks

Federal agencies are required to perform risk assessments and implement solutions to protect consumers against the identified risks of unauthorized access to information. The greater the risk, the greater is the level of assurance needed that the person seeking information access is who he or she claims to be. Federal agencies must identify the lowest level of assurance that will protect against all of the identified risks and then implement an appropriate technical solution to achieve that level of assurance, based on NIST guidelines. Federal agencies must also periodically reassess information systems “to determine technology refresh requirements.”[43]

If assumptions about how the application process would work have changed since the original assessment, a new risk assessment based on the actual application system and process is warranted. For example, the actual risks of unauthorized disclosure of consumer information may be lower than was initially assumed, if the ACA systems as implemented don’t share information in the manner originally envisioned. Following the risk assessment, HHS can determine the appropriate level of assurance and consider other security approaches available under the NIST guidelines that may reduce or eliminate the need for RIDP. This reassessment should allow HHS to protect consumers’ information while also promoting access to benefits for young adults and others experiencing barriers to applying online.

Conclusion

Streamlined access to health insurance and the protection of personal information are both priorities. Neither should come at the other’s expense. While remote identity proofing is one option for protecting consumers’ information, it presents multiple barriers that can prevent or delay consumers’ enrollment in health insurance. Many of these barriers can be avoided by taking steps identified in this paper. We encourage federal and state agencies to work together to make these improvements and to carefully consider the appropriate use of remote identity proofing, particularly when considering whether and how to implement RIDP in the context of multi-benefit online applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to representatives of the following organizations who generously shared their time and contributed information and insights about the remote identity proofing process: Federal Student Aid, U.S. Department of Education; New York Department of Health; California Pan-Ethnic Health Network; Consumers Union; Georgetown University Health Policy Institute Center for Children and Families; Kaiser Family Foundation; National Immigration Law Center; and Young Invincibles. The authors would also like to thank Stacy Dean, Dottie Rosenbaum, Judy Solomon, and Jennifer Wagner for providing valuable technical and editorial feedback and Olivia Hoppe for coordinating work related to the paper. Thanks also to John Springer who edited the paper and Rob Cady who formatted it.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities thanks the following organizations for their support for this paper:

- Center for Law and Social Policy and the Work Support Strategies Project

- California HealthCare Foundation (CHCF) based in Oakland, California

- Ford Foundation

- The JPB Foundation

- MAZON: A Jewish Response to Hunger

- Packard Foundation

- W.K. Kellogg Foundation

- Wal-Mart Foundation

Policy Basics

Health

End Notes

[1] “Guidance Regarding Identity Proofing for the Marketplace, Medicaid, and CHIP, and the Disclosure of Certain Data Obtained through the Data Services Hub,” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, June 11, 2013, http://hbex.coveredca.com/regulations/PDFs/CMS%20FAQ%20-%20Guidance%20Regarding%20Identity%20Proofing.pdf.

[2] Federal Register: Volume 78, Number 25, February 6, 2013, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-02-06/html/2013-02666.htm.

[3] “Guidance Regarding Identity Proofing for the Marketplace, Medicaid, and CHIP, and the Disclosure of Certain Data Obtained through the Data Services Hub.”

[4] “Circular No. A-130,” Office of Management and Budget, February 8, 1996, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars_a130.

[5] “E-Authentication Guidance for Federal Agencies,” Office of Management and Budget, December 16, 2003, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/memoranda/fy04/m04-04.pdf; William Burr et al., “NIST Special Publication 800-63-2: Electronic Authentication Guide,” National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce, August 2013, http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-63-2.pdf.

[6] There are four levels of assurance discussed in the NIST guidelines for electronic authentication. The lowest level, Level 1, does not require identity proofing. Levels 2 and 3 require identity proofing and allow for remote identity proofing. Level 4 requires in-person identity proofing. Ibid. CMS determined that ACA implementation requires Level 2 assurance; see “Guidance Regarding Identity Proofing for the Marketplace, Medicaid, and CHIP, and the Disclosure of Certain Data Obtained through the Data Services Hub.”

[7] “Guidance Regarding Identity Proofing for the Marketplace, Medicaid, and CHIP, and the Disclosure of Certain Data Obtained through the Data Services Hub.”

[8] Federal Register: Volume 78, Number 25, February 6, 2013, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-02-06/html/2013-02666.htm.

[9] Conversation with CMS, July 29, 2015.

[10] “Guidance Regarding Identity Proofing for the Marketplace, Medicaid, and CHIP, and the Disclosure of Certain Data Obtained through the Data Services Hub.”

[11] “Healthcare.gov: Actions Needed to Address Weaknesses in Information Security and Privacy Controls,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, GAO 14-730, September 16, 2004, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-730.

[12] Experian states that it has data on more than 215 million consumers, including credit report data and demographic data from more than 400 sources. “Precise ID: An integrated approach to the world of identity risk management,” Experian Information Solutions, 40638-0906CS, September 2006, https://www.experian.com/whitepapers/precise_id_whitepaper.pdf.

[13] Conversation with CMS, July 29, 2015.

[14] “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Observations on 18 Undercover Tests of Enrollment Controls for Health-Care Coverage and Consumer Subsidies Provided under the Act,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, GAO-15-702T, July 16, 2015, http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/671441.pdf.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “2015 Survey of Health Insurance Marketplace Assister Programs and Brokers,” Kaiser Family Foundation, August 6, 2015, http://files.kff.org/attachment/topline-2015-survey-of-health-insurance-marketplace-assister-programs-and-brokers; “Survey of Health Insurance Marketplace Assister Programs,” Kaiser Family Foundation, July 15, 2014, http://files.kff.org/attachment/survey-of-health-insurance-marketplace-assister-programs-topline.

[17] Conversation with Georgetown University Health Policy Institute Center for Children and Families, July 30, 2015.

[18] “Victims of Identity Theft, 2014,” Bureau of Justice Statistics, September 2015, http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/vit14_sum.pdf.

[19] “Application, Eligibility, and Enrollment Frequently Asked Questions,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Insurance Marketplace, https://marketplace.cms.gov/technical-assistance-resources/application-eligibility-and-enrollment-faqs.pdf.

[20] “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Observations on 18 Undercover Tests of Enrollment Controls for Health-Care Coverage and Consumer Subsidies Provided under the Act.”

[21] Michael Turner et al., “The Credit Impacts on Low-Income Americans from Reporting Moderately Late Utility Payments,” Policy & Economic Research Council (PERC), August 2012, http://www.perc.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/ADI_ML_Impacts.pdf.

[22] Ericca Maas, “Credit scoring and the credit-underserved,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, May 1, 2008, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/publications/community-dividend/credit-scoring-and-the-creditunderserved-population.

[23] “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Observations on 18 Undercover Tests of Enrollment Controls for Health-Care Coverage and Consumer Subsidies Provided under the Act.”

[24] “Application, Eligibility, and Enrollment Frequently Asked Questions,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Insurance Marketplace, https://marketplace.cms.gov/technical-assistance-resources/application-eligibility-and-enrollment-faqs.pdf.

[25] Discussion with CMS, July 29, 2015.

[26] “2011 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households,” Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, September 2012, https://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/2012_unbankedreport.pdf; Angel Padilla and Alicia Atkinson, “The Use (and Overuse) of Credit History: Credit-based ID verification creates barriers to ACA access,” National Immigration Law Center and Corporation for Enterprise Development, August 2014, http://cfed.org/blog/inclusiveeconomy/Credit_Use_Overuse.pdf.

[27] “Policy Guidance Regarding Inquiries into Citizenship, Immigration Status and Social Security Numbers in State Applications for Medicaid, State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and Food Stamp Benefits,” Letter from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture, http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/triagencyletter.pdf; “Questions and Answers,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/a-QsAsonCitizenship_0.pdf.

[28] “In FTC Study, Five Percent of Consumers Had Errors on Their Credit Reports That Could Result in Less Favorable Terms for Loans,” Federal Trade Commission, February 11, 2013, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2013/02/ftc-study-five-percent-consumers-had-errors-their-credit-reports.

[29] Discussion with New York Department of Health officials, July 30, 2015.

[30] “Job Aid: Identity Proofing in CalHEERS,” Covered California, July 11, 2014, http://hbexmail.blob.core.windows.net/eap/Job_Aid_-_Identity_Proofing_in_CalHEERS.pdf.

[31] “What is an FSA ID, and will I need it to complete the FAFSA?,” Office of Federal Student Aid, https://fafsa.ed.gov/help/FSAIDfaq01.htm.

[32] “How does the IRS Data Retrieval Tool work?,” Office of Federal Student Aid, https://fafsa.ed.gov/help/irshlp8.htm.

[33] “How do I get an FSA ID?,” Office of Federal Student Aid, https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/fafsa/filling-out/fsaid#how.

[34] “What’s the difference between a Basic and a Premium eBenefits account?,” U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, December 7, 2010, https://iris.custhelp.com/app/answers/detail/a_id/1667/~/what%E2%80%99s-the-difference-between-a-basic-and-a-premium-ebenefits-account%3F; “eBenefits Fact Sheet,” U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, https://www.ebenefits.va.gov/ebenefits-portal/downloads/eBenefits_factsheet.pdf.

[35] Section 1561 of the ACA requires the Secretary of HHS to “develop interoperable and secure standards and protocols that facilitate enrollment of individuals in Federal and State health and human services programs, as determined by the Secretary.” These standards and protocols must allow for an ability “to apply streamlined verification and eligibility processes to other Federal and State programs, as appropriate.” Section 1561 of the Affordable Care Act.

[36] Letter from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture, July 20, 2015, http://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/SMD072015.pdf.

[37] Letter from U.S. Department of Agriculture, August 7, 2013, http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/SNAP-080213.pdf.

[38] Jessica C. Smith and Carla Medalia, “Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2014,” U.S. Census Bureau, September 2015, http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p60-253.pdf.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Letter from State of California Health and Human Services Agency, Department of Health Care Services, March 24, 2015, http://www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/medi-cal/eligibility/Documents/MEDIL2015/MEDIL15-10.pdf.

[41] Letter from Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Los Angeles et al., May 21, 2014, http://board.coveredca.com/meetings/2014/5-22/PDFs/MASTER%20Comments%20to%20the%20Board%20-%20Table%20of%20Contents_May%2022,%202014.pdf.

[42] According to Experian, “It is critical to understand past and current performance of risk-based authentication policies to allow for the adjustment over time of such policies.” “A risk-based approach to agency identity proofing: Experian’s lessons learned and best practices for government,” Experian Information Solutions, Inc., 2013, http://www.experian.com/assets/public-sector/white-papers/experian-identity-proofing-white_paper.pdf.

[43] “NIST Special Publication 800-63-2: Electronic Authentication Guide.”

More from the Authors

Terri Shaw is Director of Policy at Social Interest Solutions.