West Virginia would be among the worst-harmed states in the nation under the latest version of the Senate health bill, the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA). The Senate bill would effectively end the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid; cap and cut federal Medicaid funding for seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children; increase premiums and deductibles for millions of people who get coverage through the ACA marketplaces; and weaken key protections for people with pre-existing health conditions, all while cutting taxes by hundreds of billions of dollars, largely for corporations and high-income households.

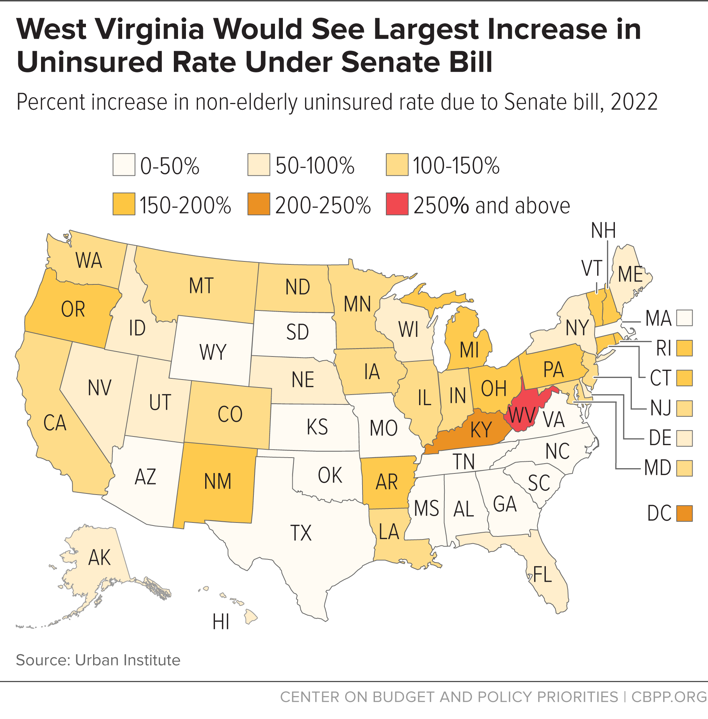

The BCRA would cause 211,000 West Virginians to lose coverage in 2022.[1] That would increase the state’s non-elderly uninsured rate from 5.0 percent to 19.8 percent, meaning that 1 in every 7 non-elderly West Virginians who would have coverage under current law would lose it as a result of the Senate bill. In percentage terms, West Virginia’s uninsured rate would increase by 299 percent, the largest increase in any state. (See Figure 1.)

Any bill that reduces access to coverage or weakens consumer protections would have a disproportionately harmful effect on West Virginians. Both the Senate bill and the House bill that passed in May are based on policies that would cause hundreds of thousands of people in West Virginia to lose access to comprehensive coverage as would repealing the ACA:

- Medicaid cuts. Medicaid covers more than half of West Virginia’s children, and one in four seniors and people with disabilities. Under the BCRA, West Virginia would see a 47 percent cut in Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) funding by 2022 (compared to a 26 percent cut nationally). Medicaid enrollment in the state would fall by more than one-half, or 263,000 people during that time. [2]

- Limited financial assistance in the marketplace. Four in ten West Virginians with marketplace coverage are age 55 or older, making consumers in West Virginia particularly vulnerable to out-of-pocket cost increases and the loss of market reforms under the Republican bills.[3] Likewise, many moderate-income families in the state could see their costs skyrocket under these proposals.

- Rolling back consumer protections. West Virginia is the state with the greatest share of people with disabilities[4] and has been among the hardest hit by the opioid epidemic. [5] Rolling back insurance protections for people with pre-existing conditions — including allowing insurers to offer plans without comprehensive benefits such as substance use disorder treatment — would put needed care out of reach for large numbers of West Virginians.

West Virginia Senator Shelly Moore Capito recently stated, “I did not come to Washington to hurt people… I have serious concerns about how we continue to provide affordable care to those who have benefits from West Virginia's decision to expand Medicaid, especially in light of the growing opioid crisis. All of the Senate health care discussion drafts have failed to address these concerns adequately.”[6] Senator Capito’s concerns can’t be addressed by any bill that maintains the BCRA’s basic structure: ending the Medicaid expansion, capping federal funds for Medicaid, and rolling back financial assistance and consumer protections in the marketplace.

Hundreds of thousands of West Virginians obtain coverage through Medicaid, including 180,000 who gained coverage through the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults. The Senate bill would end the ACA’s enhanced federal match rate for Medicaid expansion and radically overhaul — and sharply cut — the underlying Medicaid program.

The Senate bill would likely make it impossible for West Virginia to maintain its Medicaid expansion. Since the bill does not offer alternative private coverage that would be a realistic option for people in poverty, most of those losing Medicaid expansion coverage would become uninsured.

Under the Senate bill, West Virginia’s cost to maintain its expansion would rise by 50 percent compared to current law in 2021, 100 percent in 2022, and 150 percent in 2023, and would increase to 2.7 times its current-law cost — an increase of over $175 million per year — starting in 2024.[7] Faced with these cost increases, West Virginia, which has had persistent budget problems in recent years, would almost certainly find it fiscally unsustainable to continue expansion.

Since West Virginia expanded Medicaid, its adult uninsured rate has fallen by two-thirds, the largest drop in the nation.[8] Studies have found that Medicaid expansion has increased access to primary and preventive care and improved health and financial security; reduced uncompensated care costs; and put hospitals — especially small and rural hospitals –— on firmer financial footing.[9] Medicaid expansion also covered more than 100,000 low-wage workers in West Virginia.[10] Expansion has also significantly increased access to mental health and substance use disorder services, including opioid addiction treatment, according to West Virginia state officials. Thirty-three percent of Medicaid expansion enrollees in the state used mental health or substance use disorder services in 2014.[11] Rolling back expansion would roll back these gains.

Senator Capito has stated that, if Medicaid expansion were to end, she would want to see the expansion population transition to “coverage that’s just as good as the Medicaid coverage that folks are on.”[12] But while people losing coverage under expansion could access marketplace subsidies under the Senate bill, the private health insurance that would be available to them comes nowhere close to meeting Senator Capito’s standard. Instead, as the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) concluded, the large majority of those losing Medicaid expansion coverage would become uninsured: “because of the expense for premiums and the high deductibles, most of them would not purchase insurance.”[13]

- First, premiums alone would put coverage out of reach for many people with incomes below the poverty line. Under the Senate bill, this group would have to pay premiums equaling 2 percent of their income to purchase individual market coverage. A large body of research finds that premiums at this level — or even lower — put coverage out of reach for many people in poverty.[14]

-

More important, because the Senate bill eliminates cost-sharing reduction subsidies that reduce deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs for lower-income consumers, and because it links tax credits to less generous coverage (as discussed below), the benchmark plans people could purchase would have deductibles of $13,000 by 2026, according to CBO estimates.[15]

Even if they could afford their premiums, lower-income people enrolled in benchmark coverage could not afford the deductibles, copayments, and other out-of-pocket costs required to obtain health care. And, knowing that, they would be even less likely to sign up for coverage and cut back on other expenses like rent, transportation, or food in order to stay current on premiums.

- In addition, the Senate bill would allow states to waive the ACA’s requirements that plans cover essential health benefits. Evaluating a similar provision of the House bill, CBO concluded that it could result in individual market plans in up to half the country dropping coverage for services including mental health and substance use treatment.[16] People who have gained coverage under Medicaid expansion are disproportionately likely to need mental health and substance use treatment services.[17] The revised bill goes even further by allowing insurers to discriminate against people with pre-existing conditions.

The revised bill also includes $45 billion over ten years to fund treatment for opioid addiction. That funding is intended to compensate for the bill’s elimination of the ACA Medicaid expansion, which has dramatically increased access to treatment for opioid use disorders, and perhaps to compensate for waivers that would allow private plans to exclude coverage for substance use treatment.[18]

Not only would the $45 billion fall short of what experts estimate is needed for opioid treatment,[19] but replacing health insurance coverage with grant funding for treatment would always fall short as a response to the opioid epidemic. Opioid use disorder is often accompanied by other physical and mental health needs, including depression and anxiety, and people struggling with opioid use disorder need access to mental and physical health care, not just treatment for their addiction.[20] Senator Capito recently stated, “any health care bill to replace Obamacare must provide access to affordable health care coverage for West Virginians, including our large Medicaid population and those struggling with drug addiction.” Offering limited grant funding in place of coverage doesn’t meet this test.

The Senate Bill Caps and Cuts Medicaid Funding for Other West Virginians

The Senate bill would also convert virtually the entire Medicaid program to a per capita cap, with cap rates set well below projected medical costs. Today, Medicaid is a federal-state partnership, with the federal government covering a fixed share of the total cost of providing health care to vulnerable populations. Starting in 2020, the Senate bill would replace that partnership with an arbitrary cap on per-enrollee federal Medicaid funding (a “per capita cap”), which would cover a falling share of actual costs over time. Consequences include:

-

Deep cuts to federal funding. The Senate bill’s cuts due to the per capita cap would be even deeper than the already deep cuts in the House-passed health bill. CBO estimates that the bill would cut federal Medicaid funding, other than for the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, by $43 billion, or 9 percent, in 2026.

The cuts would grow even deeper in the second decade. Largely because of growing cuts from the per capita cap, CBO estimated that the total cut to federal Medicaid funding under the Senate bill would grow from 26 percent in 2026 to 35 percent in 2036.[21]

- Growing cuts to eligibility and benefits. To absorb the large and growing federal funding cuts under the per capita cap, West Virginia would have to limit eligibility, cut benefits, or — most likely — both. Certain services could be especially vulnerable to cuts. For example, home- and community-based services are an optional benefit that West Virginia already limits based on available funds. Faced with large federal funding cuts, West Virginia would almost certainly further reduce access to these services. Home- and community-based services helped some 21,000 West Virginia seniors and people with disabilities remain in their homes in 2013, instead of having to be placed in a nursing home.[22]

- Making it harder for states to respond to crises. Cuts from the per capita cap would be deepest precisely when need is greatest, since federal Medicaid funding would no longer increase automatically in response to public health emergencies like the opioid epidemic or natural disasters, such as floods.

- Disproportionate cuts for West Virginia. The state would face disproportionately large cuts due in part to the state’s relatively fast growth in per beneficiary spending. Since the cap amounts would adjust each year by a national growth rate, states with higher-than-average growth in per beneficiary costs would face deeper cuts than other states — even if this growth reflected factors beyond the state’s control, such as the aging of its senior population. West Virginia’s growth rate for several key groups has been significantly higher than the national average over the past decade, including seniors, parents, and children.

About 30,000 mostly moderate-income West Virginians obtain coverage through the marketplace. Effects on these consumers would vary by age and income, but overall, most people would be left significantly worse off, and thousands would become uninsured.

The Senate bill would make coverage and care significantly less affordable for four groups of West Virginia marketplace consumers.

-

Older marketplace consumers with incomes between 350 and 400 percent of the poverty line (about $42,000 to $48,000 for a single person). The Senate bill eliminates premium tax credits for people in this income range. In West Virginia, that would mean that a 60-year-old with income just above 350 percent of the poverty line would lose $9,764 in tax credits in 2020 and see premiums increase to at least 32 percent of her income.[23]

Marketplace consumers with incomes between $42,000 and $48,000 are often entrepreneurs, self-employed people, and early retirees, who depend on the individual market for health insurance coverage and rely on tax credits to afford it.

-

Most marketplace consumers with incomes between 200 and 350 percent of the poverty line (about $24,000 to $42,000). The Senate bill makes two major changes to tax credits for people in this income range. First, it rearranges the ACA tax credit schedule, so that older people would pay a larger share of their income in premiums and younger people a smaller share. Second, it cuts tax credits across the board by linking them to less generous coverage — effectively basing them on bronze rather than silver plans.

The latter change would leave consumers with a choice: purchase coverage with far higher deductibles, or pay more to maintain the coverage they have now. CBO projects that the deductible for a typical benchmark plan under the Senate bill would be $13,000 in 2026, compared to $5,000 under current law. Thus, most West Virginians with incomes between about $24,000 and $42,000 would either see their deductibles increase dramatically or pay significantly more in premiums to maintain the coverage they have now.

On top of that, older people in this income range would see higher premiums even if they switched to higher deductible plans, because of the Senate bill’s changes to the tax credit schedule. For example, a 60-year-old West Virginian with income of $40,000 in 2020 could choose between paying about $1,500 more in premiums and seeing her deductible double, or paying even more in premiums to maintain her current coverage.

-

Consumers with incomes between 100 and 200 percent of the poverty line (about $12,000 to $24,000 for a single person). Starting in 2020, the Senate bill eliminates the cost-sharing reduction subsidies that currently bring down deductibles, copays, and other out-of-pocket costs for lower-income marketplace consumers.[24] In combination with the bill’s provision basing tax credits on bronze plans, the result is that deductibles for people in this income group would increase from under $1,000 to about $13,000 in 2026, according to CBO.

Deductibles at these levels would almost certainly prevent lower-income people from accessing needed care. And, faced with deductibles that would prevent them from actually using their health insurance, many low-income people would likely drop coverage altogether.

-

Older people at higher income levels. For higher-income West Virginians purchasing unsubsidized coverage through the marketplace (or in the off-marketplace individual market), the major change in the Senate bill is the provision allowing insurers to charge older people premiums five times as high as younger people. In general, this change would result in premiums rising for older people, while younger people’s premiums would fall. But the increase for older people would be much larger than the decrease for younger people. For example, CBO estimates that silver plan premiums would rise by $4,450 on average (nationally) for 64-year-olds in 2026, while falling by only $1,200 for 21-year-olds.

Taking into account all of the changes discussed above, the Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that the Senate bill would result in West Virginians paying an average of twice as much in premiums (net of tax credits) for silver plans as they would under current law.[25]

The revised Senate bill further weakens protections for people with pre-existing conditions by allowing insurers to discriminate based on pre-existing conditions. The so-called “Cruz amendment” would allow insurers that offer at least one “community-rated” plan (that is, a plan where premiums would not vary based on health status) to offer additional plans subject to “medical underwriting” (plans for which insurers could vary premiums based on health history or deny coverage outright to people with expensive pre-existing conditions).[26] Under such a system, healthier people would naturally gravitate toward underwritten plans, which would offer them lower premiums. Meanwhile, the community-rated plans would disproportionately enroll people with expensive pre-existing conditions, and insurers would price them accordingly.[27]

This “adverse selection” means that, in practice, people with pre-existing conditions would face sharply higher premiums because of their health status, whether they purchased “underwritten” or “community-rated” plans. While lower-income people would be partially protected from higher premiums by the Senate bill’s subsidies, people with pre-existing conditions with incomes over 350 percent of the poverty level (about $42,000 for a single adult) would face high, sometimes unaffordable premiums, with no financial assistance.[28]

In addition, all West Virginians purchasing individual market coverage could be impacted by the Senate bill provision allowing states to waive essential health benefit standards. Commenting on a similar provision of the House bill, CBO found that states comprising about half of the nation’s population would choose to waive at least some essential health benefits rules, and that “maternity care, mental health and substance use benefits, rehabilitative and habilitative services, and pediatric dental benefits” would be the most at risk. As CBO explained, people needing these services “would face increases in their out-of-pocket costs. Some people would have increases of thousands of dollars in a year.” Likewise, services like maternity care would likely only be available as coverage “riders,” which would be priced based on the assumption that only people who needed the relevant services would buy them. CBO noted that supplemental coverage for maternity care could cost more than $1,000 a month.

Weakening essential health benefits standards would be especially harmful to people with pre-existing conditions. In 2015, 20 percent of West Virginians not living in institutions reported having a disability — the highest of any state. West Virginia has also been among the states hardest hit by the opioid epidemic, with the highest share of opioid overdose deaths of any state.[29] Undermining essential health benefits standards would jeopardize care for many people, including those with disabilities and those who need substance use disorder services. As the American Cancer Society explains, “While the Senate bill preserves the pre-existing condition protections, it allows states to waive the essential health benefits (EHBs) which could render those protections meaningless. Without guaranteed standard benefits, insurance plans would not have to offer the kind of coverage cancer patients need or could make that coverage prohibitively expensive.”[30]

The Senate bill could also result in the return of annual and lifetime limits on coverage for a significant share of the roughly 700,000 West Virginians with employer coverage.

That’s because the ACA’s prohibition on annual and lifetime limits only applies to coverage of services classified as essential health benefits. So if states eliminated or greatly weakened essential health benefits standards, plans could go back to imposing coverage limits on any services excluded from essential health benefits — including for people covered through their employer. Moreover, because large employer plans are currently allowed to select any state’s definition of essential health benefits to abide by, essential health benefits waivers in any state could mean a return to annual and lifetime limits for people in employer plans nationwide.[31] Before the ACA, 581,000 West Virginians, most of them with employer plans, had lifetime limits on their coverage.[32]

In addition, tens of millions of people each year (nationwide) lose job-based coverage and either enroll in individual market coverage or become uninsured. Thus, the availability of affordable, comprehensive individual market coverage is an important protection for West Virginians with employer coverage as well.