Medicaid Expansion: Frequently Asked Questions

End Notes

[1] KFF, Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid and Multiplier for FY 2024, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/federal-matching-rate-and-multiplier. These matching rates do not reflect the higher matching rates made available through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, as amended by the 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act.

[2] Robin Rudowitz and MaryBeth Musumeci, “‘Partial Medicaid Expansion’ with ACA Enhanced Matching Funds: Implications for Financing and Coverage,” KFF, February 20, 2019, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/partial-medicaid-expansion-with-aca-enhanced-matching-funds-implications-for-financing-and-coverage/.

[3] Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Chapter 4: Annual Analysis of Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital Allotments to States,” March 2023, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Chapter-4-Annual-Analysis-of-Medicaid-DSH-Allotments-to-States.pdf.

[4]Meghana Ammula and Madeline Guth, “What Does the Recent Literature Say About Medicaid Expansion?: Economic Impacts on Providers,” KFF, January 18, 2023, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/what-does-the-recent-literature-say-about-medicaid-expansion-economic-impacts-on-providers/.

[5] Bryce Ward, “The Impact of Medicaid Expansion on States’ Budgets,” Commonwealth Foundation, May 5, 2020, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/may/impact-medicaid-expansion-states-budgets

[6]Ibid.

[7] Jesse Cross-Call, “Medicaid Expansion Continues to Benefit State Budgets, Contrary to Critics’ Claims,” CBPP, October 9, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-expansion-continues-to-benefit-state-budgets-contrary-to-critics-claims.

[8] CBPP estimates using 2022 data from the Medicaid Budget Expenditure System, May 2023 Congressional Budget Office baseline projections, and the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission’s Medicaid and CHIP Data Book.

[9] Matthew Buettgens and Urmi Ramchandani, “2.3 Million People Would Gain Health Coverage in 2024 if 10 States Were to Expand Medicaid Eligibility,” Urban Institute, October 23, 2023, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/23-million-people-would-gain-health-coverage-2024-if-10-states-were-expand.

[10] Benjamin D. Sommers and Jonathan Gruber, “Federal Funding Insulated State Budgets from Increased Spending Related to Medicaid Expansion,” Health Affairs, 36 (5): 938–44. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1666.

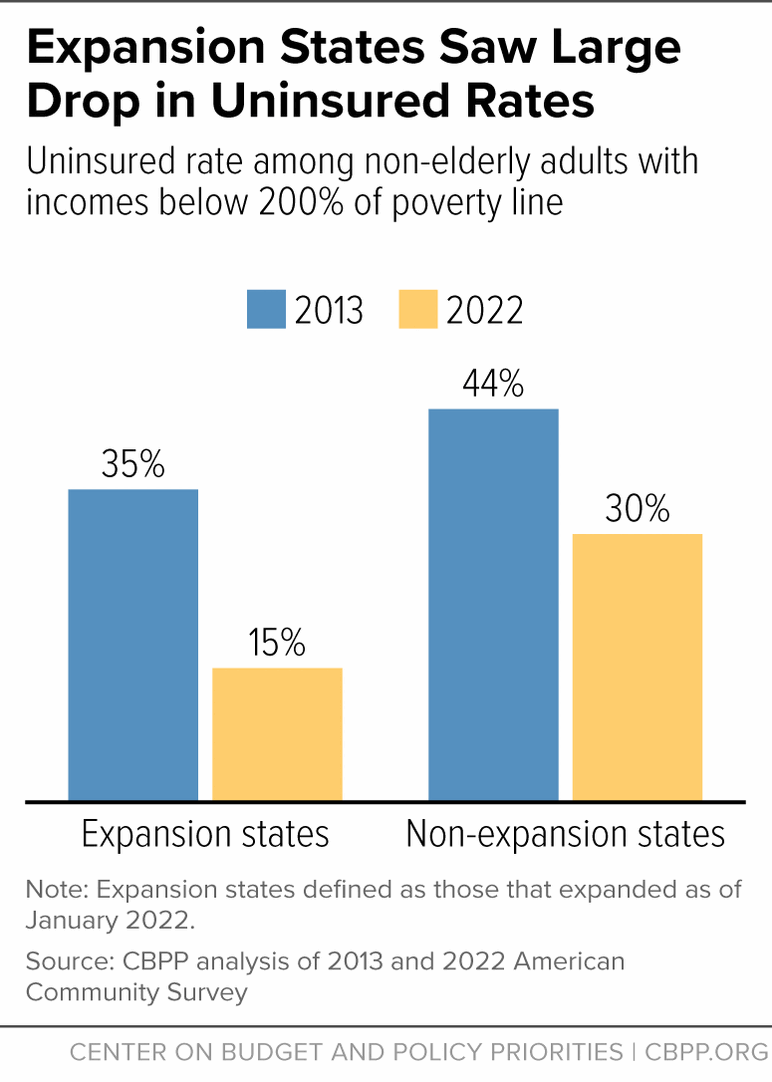

[11] CBPP analysis of American Community Survey data. As noted later in this report, the Medicaid continuous coverage requirement was in place from March 2020 to April 2023 and prevented people from being disenrolled from Medicaid, leading to record low uninsured rates in 2022. However, the results would be similar using data from years prior to the pandemic. For example, between 2013 and 2019, the uninsured rate fell from 35 to 17 percent in expansion states and from 43 to 34 percent in non-expansion states.

[12] CBPP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey.

[13] KFF State Health Facts, “Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults as a Percent of the Federal Poverty Level,” as of January 1, 2023, https://www.kff.org/affordable-care-act/state-indicator/medicaid-income-eligibility-limits-for-adults-as-a-percent-of-the-federal-poverty-level/?currentTimeframe=0&selectedRows=%7B%22states%22:%7B%22alabama%22:%7B%7D,%22florida%22:%7B%7D,%22georgia%22:%7B%7D,%22kansas%22:%7B%7D,%22mississippi%22:%7B%7D,%22south-carolina%22:%7B%7D,%22tennessee%22:%7B%7D,%22texas%22:%7B%7D,%22wisconsin%22:%7B%7D,%22wyoming%22:%7B%7D%7D%7D&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Parents%20(in%20a%20family%20of%20three)%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D.

[14] CBPP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey.

[15] Buettgens and Ramchandani, op cit.

[16] CBPP analysis of American Community Survey.

[17] Madeline Guth and Meghana Ammula, “Building on the Evidence Base: Studies on the Effects of Medicaid Expansion, February 2020 to March 2021,” KFF, May 6, 2021, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/building-on-the-evidence-base-studies-on-the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-february-2020-to-march-2021/; Madeline Guth, Rachel Garfield, and Robin Rudowitz, “The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Studies from January 2014 to January 2020,” KFF, March 17, 2020, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review/.

[18] Aaron Parzuchowski et al., “Evaluating the accessibility and value of U.S. ambulatory care among Medicaid expansion states and non-expansion states, 2012–2015,” BMC Health Services Research, July 3, 2023, https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-023-09696-x. The study uses ten measures of high-value care based on a review of the research; one definition is providing “the best care for the patient, with the optimal results for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.” Mark Smith et al., Best Care at a Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America, National Academies Press, 2013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207237/.

[19] Benjamin D. Sommers et al., “Three-Year Impacts of the Affordable Care Act: Improved Medical Care and Health Among Low-Income Adults,” Health Affairs, June 2017, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0293.

[20] Sherry Glied and Mark Weiss, “Impact of the Medicaid Coverage Gap: Comparing States That Have and Have Not Expanded Eligibility,” Commonwealth Fund, September 11, 2023, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/sep/impact-medicaid-coverage-gap-comparing-states-have-and-have-not

[21] Benjamin B. Albright et al., “Impact of Medicaid expansion on women with gynecologic cancer: a difference-in-difference analysis,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, August 7, 2020, https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(20)30835-8/fulltext.

[22] Susan Dorr Goold et al., “Primary Care, Health Promotion, and Disease Prevention with Michigan Medicaid Expansion,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, December 2019, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11606-019-05370-3.

[23] Sommers et al., op cit.

[24] Kevin N. Griffith and Jacob H. Bor, “Changes in Health Care Access, Behaviors, and Self-reported Health Among Low-income US Adults Through the Fourth Year of the Affordable Care Act,” Medical Care, Vol. 58, No. 6, June 2020, https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001321.

[25] Guth and Ammula, op. cit.

[26] Justin M. Le Blanc et al., “Association of Medicaid Expansion Under the Affordable Care Act with Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis,” JAMA Surgery, July 2020, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/article-abstract/2767686.

[27] Miranda B. Lam et al., “Medicaid Expansion and Mortality Among Patients With Breast, Lung, and Colorectal Cancer,” JAMA Network, November 2020, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2772535.

[28] Shailender Swaminathan et al., “Association of Medicaid Expansion With 1-Year Mortality Among Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease,” JAMA, December 2018, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2710505.

[29] Xu Ji et al., “Survival in Young Adults With Cancer Is Associated With Medicaid Expansion Through the Affordable Care Act,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, April 1, 2023, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36525612/.

[30] Mark Olfson et al., “Medicaid Expansion and Low-Income Adults with Substance Use Disorders,” Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, November 6, 2020, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11414-020-09738-w.

[31] Nicole Kravitz-Wirtz et al., “Association of Medicaid Expansion With Opioid Overdose Mortality in the United States,” JAMA Network, January 10, 2020, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2758476.

[32] Carrie E. Fry and Benjamin D. Sommers, “Effect of Medicaid Expansion on Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care Among Adults With Depression,” Psychiatric Services, August 28, 2018, https://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ps.201800181.

[33] Priscilla Novak, Andrew C. Anderson, and Jie Chen, “Changes in Health Insurance Coverage and Barriers to Health Care Access Among Individuals with Serious Psychological Distress Following the Affordable Care Act,” Administration and Policy in Mental Health, November 2018, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6477535/.

[34] Griffith and Bor, op. cit.

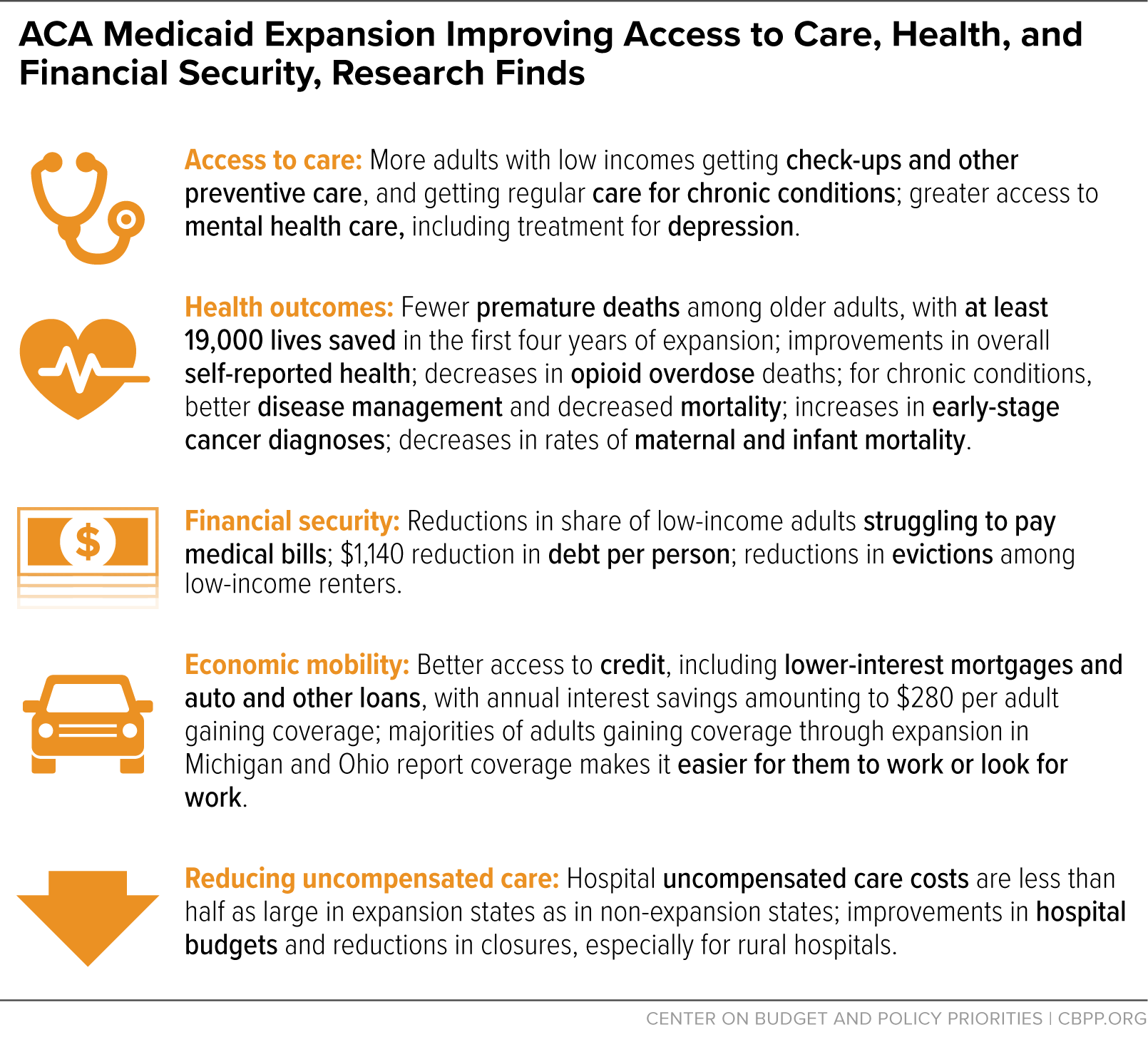

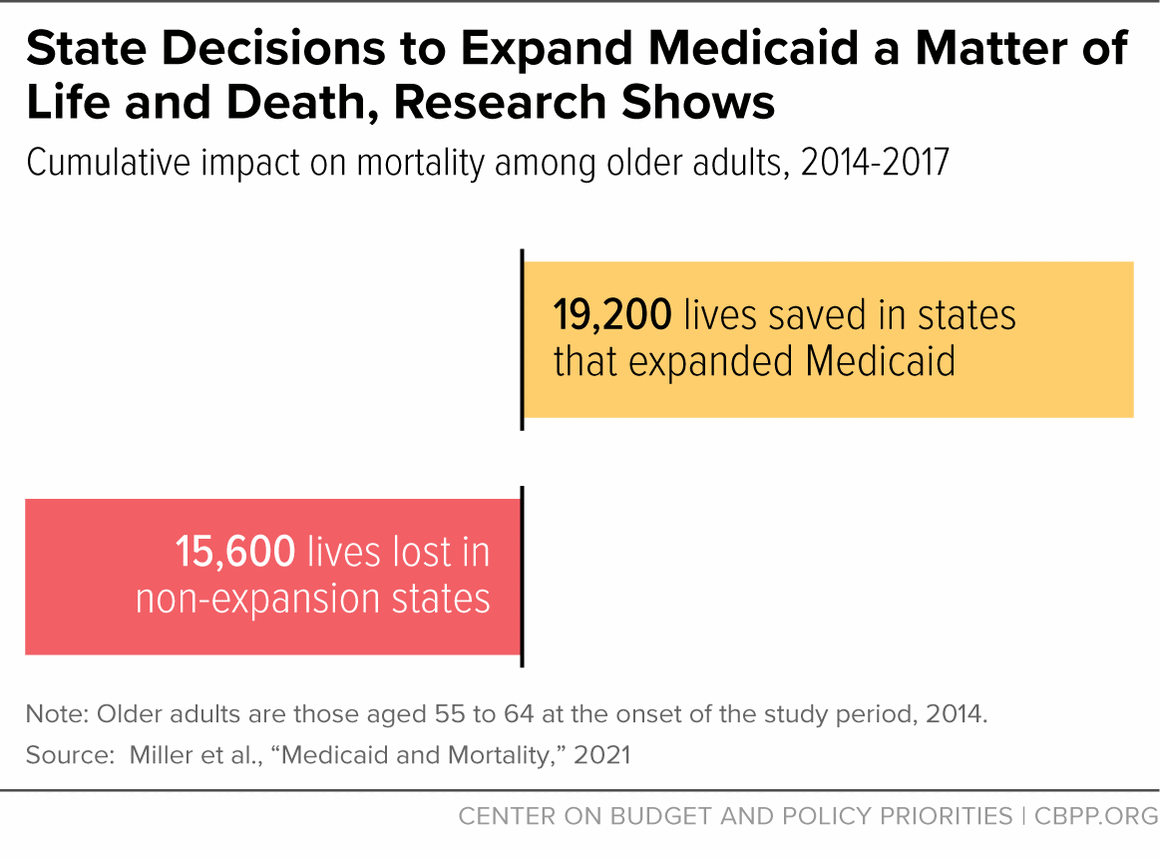

[35] Sarah Miller et al., “Medicaid and Mortality: New Evidence from Linked Survey and Administrative Data,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, January 30, 2021, https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/136/3/1783/6124639?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

[36] Matt Broaddus and Aviva Aron-Dine, “Medicaid Expansion Has Saved at Least 19,000 Lives, New Research Finds,” CBPP, November 6, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-expansion-has-saved-at-least-19000-lives-new-research-finds.

[37] Before the ACA, low-income women were eligible for Medicaid while pregnant and for 60 days postpartum, but eligibility before and after pregnancy was very restrictive.

[38] Erica Eliason, “Adoption of Medicaid Expansion Is Associated with Lower Maternal Mortality,” Women’s Health Issues, February 2020, https://www.whijournal.com/article/S1049-3867(20)30005-0/fulltext.

[39] Joanne Constantin and George L. Wehby, “Effects of Recent Medicaid Expansions on Infant Mortality by Race and Ethnicity,” American Journal of Preventative Medicine, March 2023, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0749379722004986.

[40] Chintan B. Bhatt and Consuelo M. Beck-Sagué, “Medicaid Expansion and Infant Mortality in the United States,” American Journal of Public Health, April 2018, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5844390/.

[41] Maria W. Steenland and Laura R. Wherry, “Medicaid Expansion Led To Reductions In Postpartum Hospitalizations,” Health Affairs, January 2023, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00819.

[42] Rebecca Myerson, Samuel Crawford, and Laura R. Wherry, “Medicaid Expansion Increased Preconception Health Counseling, Folic Acid Intake, and Postpartum Contraception,” Health Affairs, November 2020, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00106.

[43] Kenneth Brevoort, Daniel Grodzicki, and Martin Hackmann, “Medicaid and Financial Health,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 24002, November 2017, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w24002/w24002.pdf.

[44] Raymond Kluender et al., “Medical Debt in the US, 2009-2020,” JAMA, July 20, 2021, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8293024.

[45] Luojia Hu et al., “The Effect of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions on Financial Wellbeing,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 22170, February 2018, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w22170/w22170.pdf.

[46] Hannah Shadowen, “Virginia Medicaid Expansion: New Members Report Reduced Financial Concerns During The COVID-19 Pandemic,” Health Affairs, July 20, 2022, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01910.

[47] Brevoort, Grodzicki, and Hackmann, op. cit.

[48] Heidi Allen et al., “Early Medicaid Expansion Associated With Reduced Payday Borrowing In California,” Health Affairs, October 2017, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0369.

[49] Heidi Allen et al., “Can Medicaid Expansion Prevent Housing Evictions?” Health Affairs, September 2019, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05071.

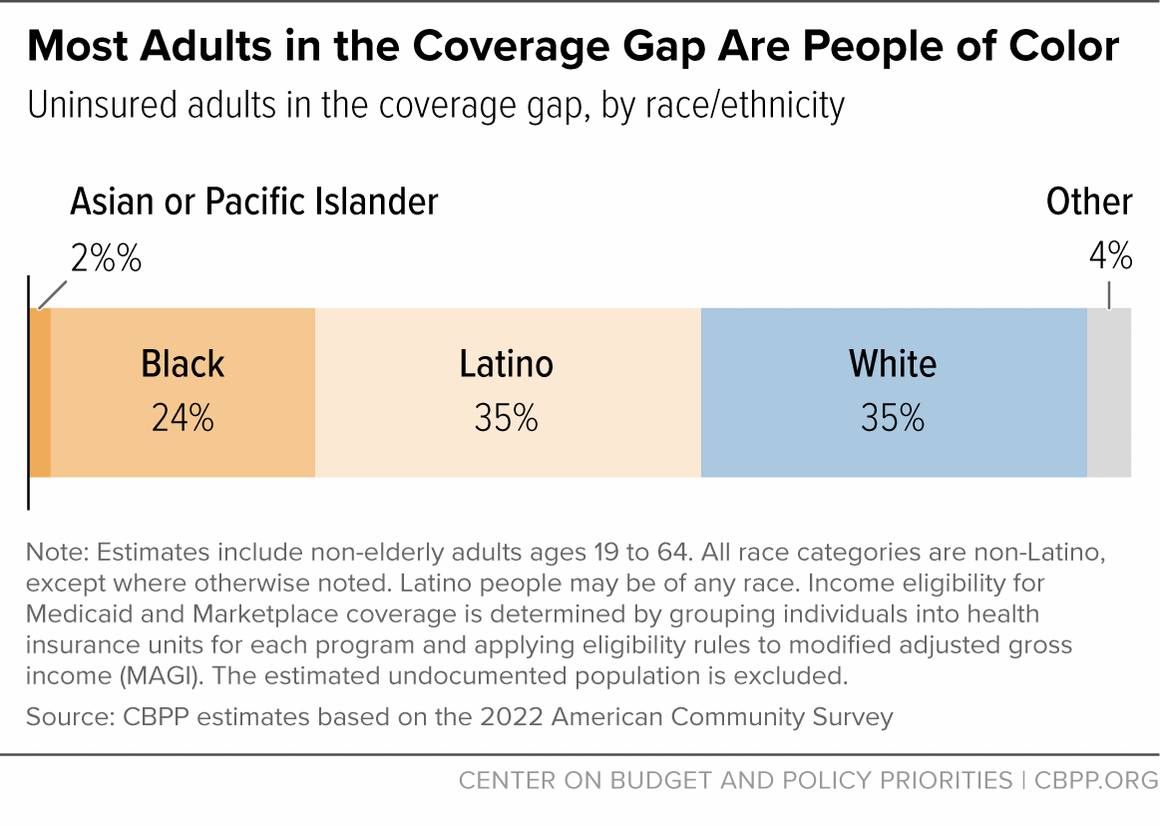

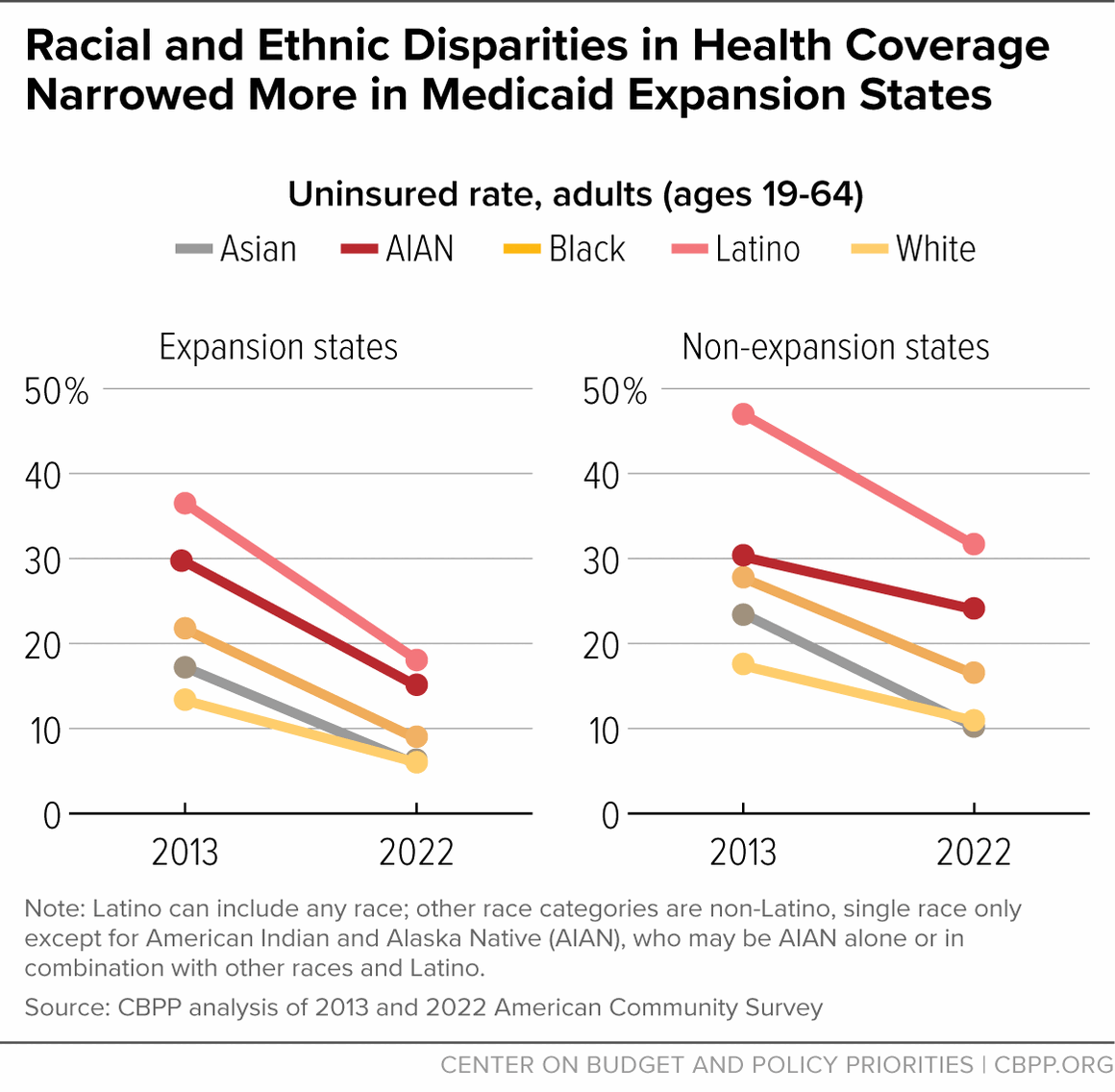

[50] CBPP analysis of 2013 and 2022 American Community Survey data. Black and white categories include individuals classified as single race, not Latino. The Latino category can include people who identify as any race.

[51]Ibid. The American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) category may be AIAN alone or in combination with other races and ethnicities.

[52]Swaminathan et al., op. cit.

[53]Erica L. Eliason, “Adoption of Medicaid Expansion Is Associated with Lower Maternal Mortality,” Women’s Health Issues, February 25, 2020, https://www.whijournal.com/article/S1049-3867(20)30005-0/fulltext.

[54] Asako S. Moriya and Sujoy Chakravarty, “Racial And Ethnic Disparities In Preventable Hospitalizations And ED Visits Five Years After ACA Medicaid Expansions,” Health Affairs, January 2023, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00460.

[55] Gregory A Metzger et al., “Association of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion with Trauma Outcomes and Access to Rehabilitation among Young Adults: Findings Overall, by Race and Ethnicity, and Community Income Level,” Journal of the American College of Surgeons, December 2021, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34656739/.

[56]Minal R. Patel et al., “Examination of Changes in Health Status Among Michigan Medicaid Expansion Enrollees From 2016 to 2017,” JAMA Network, July 10, 2020, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2768102.

[57] Buettgens and Ramchandani, op. cit.

[58] KFF State Health Facts, op. cit.

[59]Ibid.

[60]Lisa Dubay and Genevieve Kenney, “Expanding Public Health Insurance to Parents: Effects on Children’s Coverage under Medicaid,” Health Services Research, October 7, 2003, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1475-6773.00177.

[61]Julie Hudson and Asako S. Moriya, “Medicaid Expansion For Adults Had Measurable ‘Welcome Mat’ Effects on Their Children,” Health Affairs, September 2017, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0347?journalCode=hlthaff.

[62]Maya Venkataramani et al., “Spillover Effects of Adult Medicaid Expansions on Children’s Use of Preventive Services,” Pediatrics, December 2017, https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/140/6/e20170953.

[63] Jessica Schubel, “Expanding Medicaid for Parents Improves Coverage and Health for Both Parents and Children,” CBPP, updated June 14, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/expanding-medicaid-for-parents-improves-coverage-and-health-for-both-parents-and.

[64] MaryBeth Musumeci and Kendal Orgera, “People with Disabilities Are At Risk of Losing Medicaid Coverage Without the ACA Expansion,” KFF, November 2, 2020, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/people-with-disabilities-are-at-risk-of-losing-medicaid-coverage-without-the-aca-expansion/.

[65] Timothy B. Creedon et al., “Effects of Medicaid expansion on insurance coverage and health services use among adults with disabilities newly eligible for Medicaid,” Health Services Research, December 2022, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35811358/.

[66] Jean P. Hall et al., “Effect of Medicaid Expansion on Workforce Participation for People With Disabilities,” American Journal of Public Health, February 2017, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5227925/.

[67] Molly O’Malley Watts, MaryBeth Musumeci, and Priya Chidambaram, “State Variation in Medicaid LTSS Policy Choices and Implications for Upcoming Debates,” KFF, February 26, 2021, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/state-variation-in-medicaid-ltss-policy-choices-and-implications-for-upcoming-policy-debates/.

[68] Jesse Cross-Call, “Opponents Recycling Falsities About Medicaid Expansion’s Impact on Seniors, People With Disabilities,” CBPP, October 11, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/opponents-recycling-falsities-about-medicaid-expansions-impact-on-seniors-people-with.

[69] Alice Burns, Maiss Mohamed, and Molly O’Malley Watts, “A Look at Waiting Lists for Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Services from 2016 to 2023,” KFF, November 29, 2023, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/a-look-at-waiting-lists-for-medicaid-home-and-community-based-services-from-2016-to-2023https://www.kff.org/report-section/key-state-policy-choices-about-medicaid-home-and-community-based-services-appendix-tables/; KFF, “Medicaid HCBS Waiver Waiting List Enrollment, by Target Population and Whether States Screen for Eligibility,” https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-hcbs-waiver-waiting-list-enrollment-by-target-population-and-whether-states-screen-for-eligibility/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

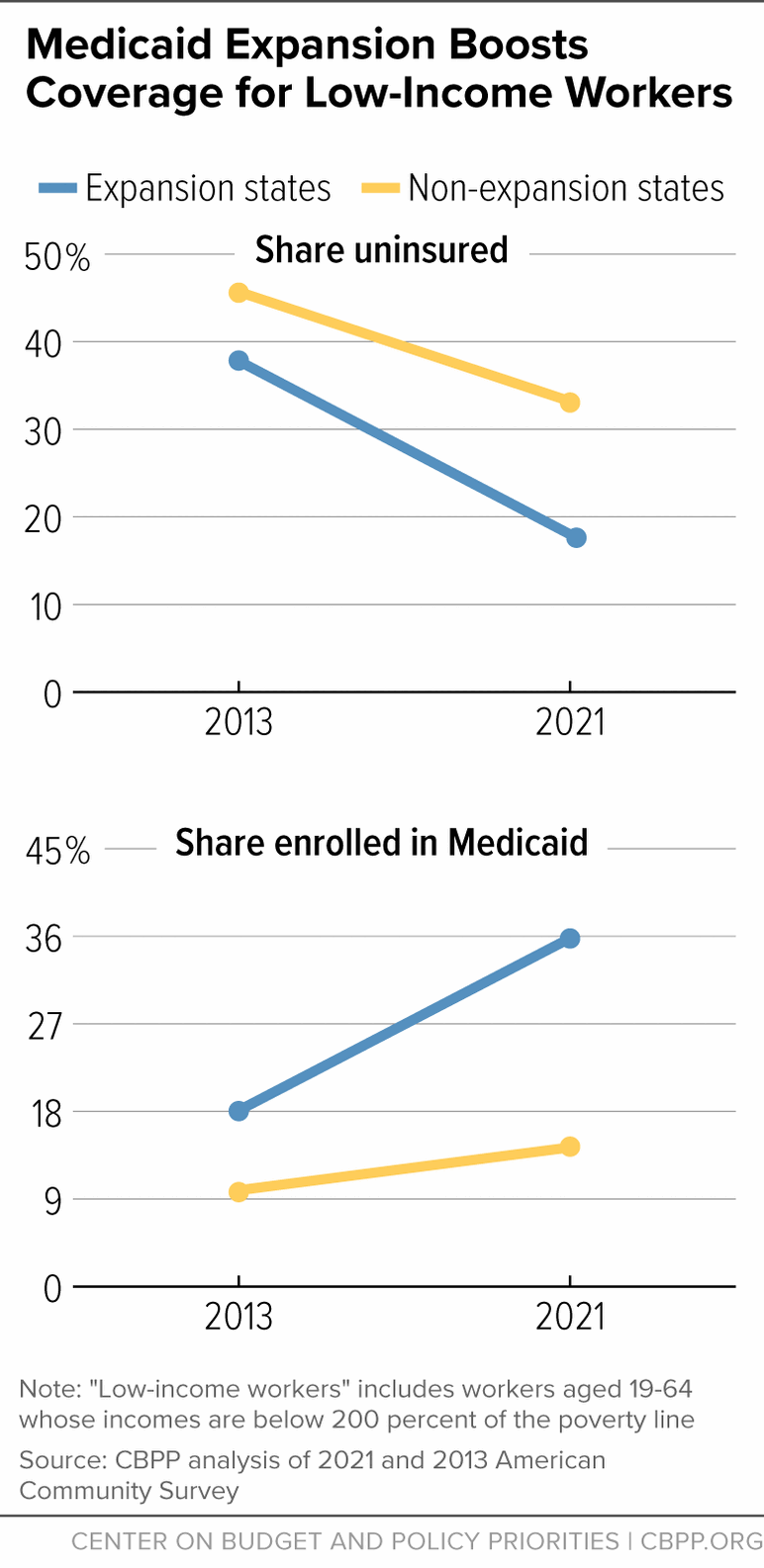

[70] Madeline Guth et al., “Understanding the Intersection of Medicaid & Work: A Look at What the Data Say,” KFF, April 24, 2023, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/understanding-the-intersection-of-medicaid-work-a-look-at-what-the-data-say/. Includes adults under age 65 who were not receiving Supplemental Security Income or Medicare. CBPP analysis of 2023 March Current Population Survey.

[71] For example, one study found that low-income workers in expansion states did not lose jobs, switch jobs, or change from full- to part-time work more frequently than low-income workers in non-expansion states. Angshuman Gooptu et al., “Medicaid Expansion Did Not Result In Significant Employment Changes Or Job Reductions In 2014,” Health Affairs, January 2016, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0747.

[72] Ohio Department of Medicaid, “2018 Ohio Medicaid Group VIII Assessment: A Follow‐Up to the 2016 Ohio Medicaid Group VIII Assessment,” August 2018, https://medicaid.ohio.gov/static/Resources/Reports/Annual/Group-VIII-Final-Report.pdf; Renuka Tipirneni et al., “Changes in Health and Ability to Work Among Medicaid Expansion Enrollees: A Mixed Methods Study,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 34, No. 2, February 15, 2019, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30519839/.

[73] Jean P. Hall et al., “Effect of Medicaid Expansion on Workforce Participation for People With Disabilities,” American Journal of Public Health, February 2017, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5227925/.

[74] Laura Harker, “Pain But No Gain: Arkansas’ Failed Medicaid Work-Reporting Requirements Should Not Be a Model,” CBPP, August 8, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/pain-but-no-gain-arkansas-failed-medicaid-work-reporting-requirements-should-not-be

[75] Ibid.

[76] Ibid.

[77] LaDonna Pavetti et al., “Expanding Work Requirements Would Make It Harder for People to Meet Basic Needs,” CBPP, March 15, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/expanding-work-requirements-would-make-it-harder-for-people-to-meet.

[78] Leah Chan, “Money Matters: Comparing the Costs of Full Medicaid Expansion to the Pathways to Coverage Program,” GBPI, January 11, 2023, https://gbpi.org/money-matters-comparing-the-costs-of-full-medicaid-expansion-to-the-pathways-to-coverage-program/.

[79] Uncompensated care refers to “health care or services provided by hospitals or other health care providers that don’t get reimbursed.” (Retrieved from https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/uncompensated-care/.) Operating margin refers to “net income from patient care (operating revenue minus operating expenses) divided by revenue from patient care.” (Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10114034/.)

[80] Ammula and Guth, op. cit.

[81] David Dranove, Craig Garthwaite, and Christopher Ody, “The Impact of the ACA’s Medicaid Expansion on Hospitals’ Uncompensated Care Burden and the Potential Effects of Repeal,” Commonwealth Fund, May 2017, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2017/may/impact-acas-medicaid-expansion-hospitals-uncompensated-care.

[82] Fredric Blavin and Christal Ramos, “Medicaid Expansion: Effects on Hospital Finances and Implications for Hospitals Facing COVID-19 Challenges,” Health Affairs, January 2021, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00502.

[83] Richard C. Lindrooth et al., “Understanding The Relationship Between Medicaid Expansions And Hospital Closures,” Health Affairs, January 2018, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0976.

[84] Joan Alker and Jack Hoadley, “Health Insurance Coverage in Small Towns and Rural America: The Role of Medicaid Expansion,” Georgetown University Center for Children and Families and the University of North Carolina NC Rural Health Research Program, September 2018, https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/FINALHealthInsuranceCoverage_Rural_2018.pdf.

[85] Zachary Levinson, Jamie Godwin, and Scott Hulver, “Rural Hospitals Face Renewed Financial Challenges, Especially in States That Have Not Expanded Medicaid,” KFF, February 23, 2023, https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/rural-hospitals-face-renewed-financial-challenges-especially-in-states-that-have-not-expanded-medicaid/.

[86] Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, “Rural Hospital Closures,” accessed February 1, 2024, https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures/.

[87] Michael Topchik et al., “The Rural Health Safety Net Under Pressure: Rural Hospital Vulnerability,” Chartis Center for Rural Health, February 2020, https://www.chartis.com/sites/default/files/documents/Rural%20Hospital%20Vulnerability-The%20Chartis%20Group.pdf.

[88] American Hospital Association, “Rural Report: Challenges Facing Rural Communities and the Roadmap to Ensure Local Access to High-quality, Affordable Care,” February 2019, https://www.aha.org/system/files/2019-02/rural-report-2019.pdf; National Institutes of Health, “Rural Hospital Closures Fuel Rising Demand and Costs at Nearby Hospitals,” March 7, 2023, https://ncats.nih.gov/news-events/news/rural-hospital-closures-fuel-rising-demand-and-costs-at-nearby-hospitals.