President Trump’s 2018 budget includes $2.5 trillion in cuts over the next decade to low-income programs like SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly food stamps) and Medicaid that help struggling families afford the basics.[1] The Administration has justified many of these proposed cuts by suggesting that its policies will result in people finding work, ignoring that many program participants either already work or are unable to do so. When asked about the budget’s massive SNAP cuts, for instance, Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney said, “Folks who are out there who are on food stamps and want to work, we’ll be able to work with them to solve the problem.”[2]

But the proposals put forward in this budget show that this is simply untrue. That’s because the budget’s cuts in job training and a range of other proposals would make it harder for people to succeed in the labor market — and would hurt the millions of program participants already working — making it clear that the budget’s real goal is to make large cuts in these areas, not to help those the economy has left behind get ahead.

A plan to increase employment and earnings among jobless or under-employed workers with low skills would include: new investments in high-quality job training, including job training slots for those facing a cutoff of SNAP benefits because they are jobless; efforts to make college more affordable; subsidized jobs for those who need to build work experience and skills; and investments in child care so parents can work or participate in training or education programs. But this budget includes none of these. To the contrary, it features cuts in job training; proposals that would make college more expensive; cuts in programs that support child care; provisions that would increase work disincentives in Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance; and a proposal that would terminate food assistance to certain jobless individuals without offering them job training or work opportunities.

Taken together, these proposals will make it significantly harder for people left behind by the economy to move up the economic ladder.

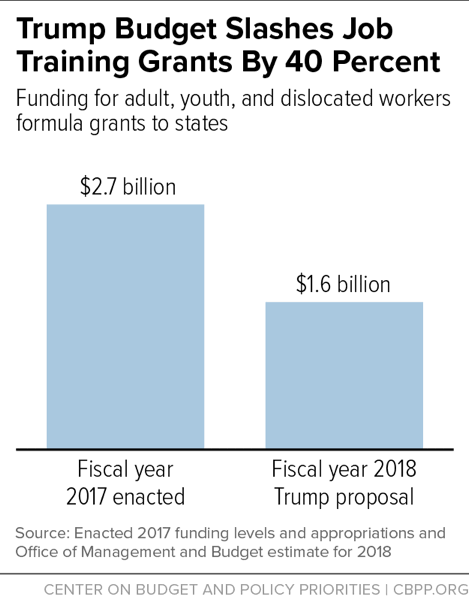

The budget would cut core job training programs by 40 percent in 2018 alone. The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) provides funding to states and communities for job training for adults, dislocated workers (generally those who have recently lost jobs due to layoffs or those who receive or have exhausted unemployment insurance benefits), and young people (with an emphasis on youth who are neither in school nor working). The Administration is proposing to cut funding for these grants by $1.1 billion, from $2.7 billion in 2017 to $1.6 billion in 2018 (see Figure 1). Moreover, these cuts are likely to grow deeper over time under the President’s budget given the sharp cuts in non-defense discretionary funding the budget proposes for the years after 2018.

The Administration has called for these deep cuts despite Congress’ passage in 2014 of bipartisan legislation to update these job training programs, including placing a greater emphasis on training for in-demand occupations, encouraging replication of program models with evidence of effectiveness, and encouraging work-based learning models that allow workers to earn while they are learning.[3] WIOA also strengthened performance measurement so that workers have the information they need to choose the most effective job training programs.

The budget also cuts the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program by $22 billion over ten years, or 13 percent. States use TANF funds to provide limited amounts of basic cash assistance as well as services to poor families with children, including employment services and job training.

The budget would make college less affordable for many low-income students. The budget proposes significant cuts to student aid, including eliminating a campus-based grant program for low-income students, cutting work-study opportunities in half, and making student loans more expensive for many low- and moderate-income students by eliminating subsidized loans, among other changes.[4] It also fails to extend a provision, set to expire after the 2017-2018 school year, that adjusts the Pell Grant for inflation. As a result, Pell Grants will cover a decreasing share of the cost of going to college under the Administration’s plan.[5] Currently, Pell Grants cover only an average of less than 30 percent of the cost of attending a public four-year college, its lowest point in the program’s more than 40-year history.[6] If the Pell Grant does not adjust for inflation, it will become even less sufficient. It is notable that the President’s budget includes more than $140 billion in student loan cuts overall but does not reinvest any of those savings to protect the Pell Grant from inflation.

The budget has no proposals to create subsidized jobs. Subsidized jobs can be used to help those who cannot find work and who need help building skills or work experience. They also provide an opportunity for those who can’t find a job to work and earn money to meet their basic needs. During the recession, using funds from the TANF Emergency Fund, states created 260,000 jobs, which helped people earn money they could use to pay their rent and put food on the table. The President’s budget has no specific proposals to create jobs for those who want, but can’t find, them.

The budget would set funding for the child care block grant just below the 2017 funding level and cut two programs — TANF and the Social Services Block Grant (SSBG) — that many states use to fund child care. Child care is key to helping parents work when their earnings are too low to afford the high cost of care — and is central to parents’ ability to attend job training or go to school. Due to inadequate funding, today just 1 in 6 children who quality for child care assistance because they have low- or moderate- incomes receive it.

Rather than putting forward a plan that would help struggling families afford the high cost of child care, the budget would slightly reduce funding for the basic child care block grant and make significant cuts to two other important funding sources states use for child care — TANF (described above) and the SSBG, the annual funding for which now equals $1.7 billion, and which the budget proposes to eliminate completely.[7] In 2014, some $5.4 billion in TANF and SSBG funds were used for child care.[8]

The budget would put in place new work disincentives in Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance. Medicaid and SNAP currently have provisions that mean when a poor adult is able to get a job or increase her earnings modestly, the individual or family does not lose health care or food assistance entirely because of a “benefit cliff.” The budget would eliminate both provisions and create new work disincentives in both programs. And in housing, the proposed rent increase for those receiving housing assistance would increase rents somewhat more quickly as earnings rise.

-

The Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion currently allows adults (in expansion states) to remain eligible for Medicaid until their incomes reach 138 percent of the poverty line ($16,643 for a single person or $28,180 for a family of three in 2017), at which point they can receive premium tax credits (that phase down as income rises) to purchase private insurance coverage in the marketplace.

The House-passed Republican health bill would effectively eliminate the Medicaid expansion, causing many parents to lose Medicaid coverage except at the very lowest income levels. This would mean that when parents get a job or their earnings rise from very low levels, they will become ineligible for Medicaid — creating a real downside to finding a job or increasing earnings.

The budget, through its inclusion of the House health bill, creates a further disincentive for Medicaid beneficiaries to work by allowing states to freeze their Medicaid expansion enrollment. That means that any low-wage worker who leaves Medicaid — whether for a higher-paying job or to enroll in employer coverage — will be taking a big risk: she probably won’t be able to get Medicaid coverage again if she needs it.[9]

- In SNAP, a state option allows benefits to continue to phase down gradually — falling by about 30 cents for every additional dollar earned — if a family’s income rises modestly above the typical cutoff at 130 percent of the poverty line ($26,546 for a family of three). The budget would eliminate this option, forcing states to terminate modest but important benefits to working families whose income rises modestly above 130 percent and reinstating a benefit cliff.

- The budget proposes to increase rents on some households receiving housing assistance. One of these changes would result in rents increasing from the current 30 percent to 35 percent of income for many families (while also changing how income is measured to increase rental payments further for some families). This change would mean that affected working households would face a higher “marginal tax rate” — that is, as their earnings rose, their rent would rise more quickly.

The budget could make it harder for people with health conditions — including opioid addiction — to find and hold a job. Most non-disabled adults with Medicaid coverage do work. For those who don’t, more than one-third report an illness or disability — such as diabetes or a substance use disorder — that keeps them from working. By assuming passage of the House Republicans’ health bill, the budget would allow states to impose a work requirement on most adults with Medicaid coverage, which could block many people from getting the care they need to improve their health and join the workforce.[10] The House bill includes few protections around the design or implementation of these work requirements, which means that many people could be required to work even if they are taking care of an aging family member, can’t find a job, or can’t work due to a health condition. With access to treatment, some people may be able to join the workforce; by blocking access to care, a work requirement may make it more difficult for people with conditions such as diabetes or opioid addiction to work.

The budget fails to provide work or job training to SNAP recipients facing termination of their benefits because they are jobless while at the same time forcing states to terminate benefits even in areas of high unemployment. The President’s budget would severely restrict SNAP benefits for unemployed childless adults living in areas with high unemployment by allowing waivers of a three-month time limit only for areas with unemployment rates of 10 percent or more — a more stringent standard for high unemployment than is currently in place. Since few areas have sustained unemployment rates that high, close to 1 million individuals could lose benefits in a typical month even if working less than half time or looking for work. Claims that the Administration will “do everything we can to help you find a job”[11] ring hollow as the budget would do nothing to provide job training or work opportunities to individuals facing this time limit; rather those who are out of work and unable to access job training would simply lose food assistance.

The budget assumes large savings from increasing employment among people with disabilities and thereby reducing receipt of Social Security Disability Insurance and the Supplemental Security Income program but has no real plan for how it would do so. The budget calls for testing new approaches to increasing employment among people with disabilities and then assumes large savings will result. But evidence shows that given the age and impairments of those receiving these benefits — and their high death rates — large savings are unlikely.[12]

The Administration’s budget fundamentally misunderstands the individuals and families who receive assistance such as SNAP or Medicaid. Millions of working families are among the programs’ beneficiaries. The President’s budget would lead to sharp cuts in health care and food assistance to these families struggling to make ends meet while working in low-wage jobs.

To be sure, the Administration claims that other parts of its agenda — including its deregulatory agenda, infrastructure proposal, and trade policies — will promote growth and create jobs. While there is bipartisan support for improving the nation’s aging infrastructure, few mainstream economists think that the Administration’s agenda will lead to dramatically faster economic growth. Moreover, while a strong labor market improves employment outcomes and reduces poverty, helping the most disadvantaged workers requires additional efforts — including job training, support for higher education, and child care. Leaving people without access to health care or making it impossible for them to put food on the table will not make them better able to work.