- Home

- 13 States Face Total Budget Shortfall Of...

13 States Face Total Budget Shortfall of at Least $23 Billion in 2009; 11 Others Expect Budget Problems

Economy, States’ Past Fiscal Decisions Are Largely To Blame

New Fiscal Year Brings No Relief From Unprecedented State Budget Problems

Summary

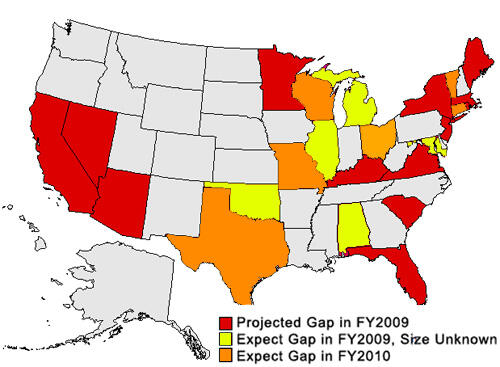

Thirteen states, including several of the nation’s largest, face a combined budget shortfall of at least $23 billion for fiscal 2009. Another 11 states expect budget problems next year or the year after. The initial reports for 2009, which runs from June 2008 to June 2009 for most states, suggest states are returning to a time of budget deficits.

Some of the fiscal problems are due to economic conditions outside states’ control. The bursting of the housing bubble has reduced state sales tax revenue collections from sales of furniture, appliances, construction materials, and the like. Property tax revenues have also been affected, and local governments will be looking to states to help address the squeeze on local and education budgets.

In many states, however, these economic problems are being magnified by endemic budget weaknesses created by past state decisions about taxes and expenditures. Some states have relied on one-time revenues (such as the sale of state assets) to balance their budgets, have enacted tax cuts — often multi-year — without accurately assessing their affordability, and have failed to address structural weaknesses in their budgets.

In November, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reviewed state fiscal reports and conducted a phone and email survey of state legislative and executive budget officials in the 50 states and DC. The findings suggest the combination of a slowing economy and ill-considered state policies has already weakened state fiscal conditions:

- Nearly half of the states surveyed reported that they anticipate budget problems.

- Ten states have prepared revenue and spending projections for FY2009 and have found that revenues will fall short of the amount needed to support current services. They are Arizona, California, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Virginia. Three other states, Florida, Kentucky, and South Carolina are now projecting weaker than expected revenues for FY2009 that they anticipate will lead to budget gaps. The budget gaps total $23 - $30 billion, averaging 7.1 - 9.4 percent of these states’ general fund budgets. (See Table 1.)

| TABLE 1A: | ||

| Amount | Percent of FY2008 General Fund | |

| Arizona | $830 million - $1.8 billion | 7.8 - 16.9% |

| California | $9.8 billion - $14 billion | 9.4% - 13.4 |

| Maine | $57 million | 1.8% |

| Massachusetts | $1.2 billion | 4.2% |

| Minnesota | $373 million | 2.2% |

| Nevada | $286 million | 8.6% |

| New Jersey | $2.5 - $3.5 billion | 7.6 - 10.6% |

| New York | $4.3 billion | 7.9% |

| Rhode Island | $400 - $450 million | 11.8 - 13.2% |

| Virginia | $1.2 billion | 6.9% |

| TABLE 1B: | ||

| Amount | Percent of FY2008 General Fund | |

| Florida | $1.4 - $2.4 billion | 4.5 - 7.8% |

| Kentucky | $212 million | 2.3% |

| South Carolina | $430 million | 6.4% |

| 13-STATE TOTAL | $23.0 - $30.2 billion | 7.0 - 9.4% |

- Another 11 states report that their budgetary balance is precarious, with gaps likely to open up in FY2009 and/or FY2010. In six of them — Alabama, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Oklahoma, and Vermont — it is clear that there will be gaps in the FY2009 budget, but the size of the expected deficit is not clear. Analysts in the five other states — Connecticut, Missouri, Ohio, Texas, and Wisconsin — are projecting budget gaps a little further down the road, in FY2010 and beyond.

This brings the total number of states identified as facing budget gaps to 24 — close to half of all states. The remaining 26 states did not foresee FY2009 budget gaps at the time of the survey either because their budgets remain strong or because they have not yet prepared updated revenue and spending projections for fiscal year 2009. Some mineral-rich states — such as New Mexico, Alaska, Montana and Wyoming — are seeing revenue growth as a result of high oil prices. Other regions’ economies are less affected by the national economic problems. For example, states with high levels of exports are benefiting from the falling value of the dollar. Nevertheless, the list of states facing budget gaps is likely to grow as additional states take stock of their FY2009 budgets in preparation for the upcoming legislative session.

In many of these states, past policies are adding to the stress caused by economic conditions:

- Florida, Michigan, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Virginia are feeling the effects of past tax reductions that are proving unaffordable.

- Arizona, New York, and Rhode Island have enacted tax cuts that are being phased in over a number of years. While revenues were sufficient to balance the budget in the year the tax cuts were adopted, problems are developing as the state faces the tax cuts’ full cost.

- Many of the states projecting budget gaps — Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Illinois, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia — face a structural budget imbalance, which means that revenues routinely grow more slowly than the cost of providing the same level of state services.

- By using one-time funding sources or surpluses to fund ongoing tax cuts or expenditure increases, Arizona, California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Texas, and Virginia ended up with budget gaps when these funding sources were depleted.

In states facing budget gaps, the consequences could be severe — for residents as well as the economy. Unlike the federal government, states cannot run deficits when the economy turns down; they must cut expenditures, raise taxes, or draw down reserve funds to balance their budgets. Even if the economy does not fall into a recession as it did in the earlier part of this decade, actions will have to be taken to close the budget gaps states are now identifying. The experience of the last recession is instructive as to what kinds of actions states may take.

- Cuts in services like health and education. In the last recession, some 34 states cut eligibility for public health programs, causing well over 1 million people to lose health coverage, and at least 23 states cut eligibility for child care subsidies or otherwise limited access to child care. In addition, 34 states cut real per-pupil aid to school districts for K-12 education between 2002 and 2004, resulting in higher fees for textbooks and courses, shorter school days, fewer personnel, and reduced transportation.

- Tax increases. Tax increases may be needed to prevent the types of service cuts described above. However, the taxes states often raise during economic downturns are regressive — that is, they fall most heavily on lower-income residents.

- Cuts in local services or increases in local taxes. While the property tax is usually the most stable revenue source during an economic downturn, that is not the case now. If property tax revenues decline because of the bursting of the housing bubble, localities and schools will either have to get more aid from the state — a difficult proposition when states themselves are running deficits — or reduce expenditures on schools, public safety, and other services.

Expenditure cuts and tax increases are problematic policies during an economic downturn because they reduce overall demand and can make the downturn deeper. The federal government — which can run deficits — can provide assistance to states and localities to avert these “pro-cyclical” actions.

States’ Own Actions Have Left Them More Vulnerable to a Downturn

Unaffordable tax cuts, unaddressed structural budget problems, and the use of gimmicks and one-time revenues to balance budgets have weakened state fiscal conditions. These problems can leave states especially vulnerable to economic swings.

Many Tax Cuts Proving Unaffordable

During periods of economic growth, it is common for states to feel flush with funds and to cut taxes. But some of these tax cuts can cause lasting harm. When states overestimate their ability to afford tax cuts, they undermine the revenue streams necessary to pay for education, transportation, health care, and other public services.

For example, during the economic boom of the middle and late 1990s, many states enacted tax cuts, a number of them quite large. Proponents argued that big tax cuts would improve their state’s fiscal and economic performance. A Center study of the 16 states that enacted the largest tax cuts, however, found that the promised improvements did not occur.[1] Moreover, when the economic boom ended six years ago, states that had enacted costly tax cuts had larger budget problems and larger job losses than states that had shown more fiscal restraint.

State Spending Remains Below Pre-Recession Levels

Many states have never fully recovered from the fiscal crisis in the early part of the decade. This fact heightens the potential impact on public services of the deficits states are now projecting.

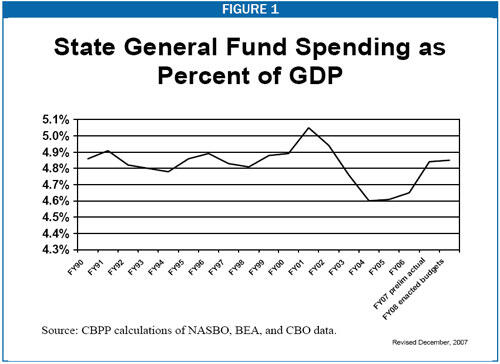

State expenditures fell sharply relative to the economy during the 2001 recession, and for all states combined they remain below the FY2001 level. (See Figure 1.) In 18 states, general fund spending for FY2008 — six years into the economic recovery — remains below pre-recession levels as a share of the gross domestic product.

This pattern is resurfacing in the current slowdown. States that have cut taxes significantly in recent years, such as Florida, Michigan,[2] New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Virginia,[3] now face significant budget gaps.

Part of the problem is that the true cost of many of the recent tax cuts was hidden at the time they were adopted. For example, nine of the ten states that enacted significant tax cuts in 2006 “backloaded” them so the bulk of the costs would occur in future years — i.e., in years for which budgets had not yet been written.[4] By 2009, these tax cuts will become much more costly. Backloaded tax cuts are one of the reasons Arizona, New York,[5] and Rhode Island are projecting budget gaps

Structural Budget Problems Are Common

State revenues have an imperfect track record as a stable and reliable source of funding for services. Part of the problem is cyclical: state revenues decline when the economy experiences a downturn like the current one. In addition, many states face a more enduring problem, often called a structural deficit — the chronic inability of state revenues to grow in tandem with economic growth and the cost of government.

Structural deficits largely result from a state’s failure to modernize its revenue system to reflect changes in the economy, such as the growing importance of the service sector. Several states have changed their revenue systems little since the 1930s or 1940s; others have revenue systems that are 20 to 30 years out of date.

No research has definitively determined how many states have structural deficits, but most states are generally thought to have this problem to some degree. The Center has identified ten factors that make a state vulnerable to structural budget problems.[6] Eleven of the states currently facing fiscal problems — Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia — have at least seven of these ten factors and thus are at highest risk of a structural deficit. In addition, state-level analyses in Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, and New York have identified long-standing structural gaps.

Use of One-Time Revenue and Budget Gimmicks

When a state balances its budget using one-time resources or surpluses, it requires faster than normal growth the following year simply to maintain existing programs. This is because the state must replace the one-time revenue in the budget and also find funds to cover the normal growth in the cost of services. States that have gone down this road are likely to find a revenue slowdown like the current one doubly difficult to deal with.

Arizona, California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Texas, and Virginia balanced their budgets in FY2006 and FY2007 using significant amounts of one-time revenues and/or budget gimmicks. This includes the use of temporary budget surpluses or proceeds from sales of assets, “borrowing” from pension funds by skipping or postponing deposits, securitizing revenue streams such as tobacco settlement payments,[7] and delaying major payments such as aid to local governments. The budget gaps these states now must struggle to close are one consequence of these actions.

Inadequate Rainy-Day Funds

Times of economic growth provide an opportunity for states to build up rainy-day funds and other reserves. At the end of FY2006, state general fund balances totaled 11.5 percent of total state spending, roughly the same level of reserves states had going into the last recession — and an amount that proved inadequate to avoid major spending cuts. Most states’ rainy day funds in FY2006 were well below the threshold of 15 percent of annual spending that the Government Finance Officers Association suggests is prudent and that CBPP research suggest would be needed to weather a recession.[8]

Despite this, balances declined in FY2007 to 9.6 percent of budgets and are projected to decline again in FY2008, to 6.7 percent. This decline is another indication of the extent to which states have used one-time resources to balance their budgets in good fiscal times. It also leaves many states ill-prepared to face an economic slowdown.

An economic slowdown is not the time for states to build up their reserves. But by demonstrating the consequences of inadequate reserves, it can encourage states to change the policies that determine how much money they set aside in good economic times so they are in a better position when the next slowdown occurs.

Conclusion

Some of the reasons that many states’ fiscal health is deteriorating — such as economic doldrums and reduced federal assistance — are out of state policymakers’ control. But state policy influences many aspects of state fiscal conditions.

States that need to close a current or projected deficit should consider all of their options, including increasing ongoing revenues. States that enacted deep tax cuts during the recent period of economic growth should be particularly concerned about whether their revenue system can maintain the public services residents want and need.

In addition, if the economy does fall into a recession the federal government should consider aiding states earlier, rather than waiting until the downturn is nearly over — as it did in the early part of the decade.

| APPENDIX | ||

| State | Source | Notes |

| Alabama | Arise Policy Project | Gap is likely due to expiration of Katrina aid, inflation, and health costs increases but don’t know size. |

| Arizona | Joint Legislative Budget Committee | Deficits projected for FY2008 and FY2009. High estimate assumes FY2008 gap is carried over to FY2009. |

| California | Legislative Analysts Office (low); Press reports of Governor’s budget staff estimates (high) | Assumes $2 billion gap carried over from FY2008. |

| Connecticut | ||

| Florida | Revenue Estimating Conference | Shortfalls are projected for FY2008 and FY2009. High estimate assumes FY2008 gap is carried over to FY2009. |

| Illinois | Voices for Illinois Children based on reports from the Comptroller and the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability | |

| Kentucky | State Budget Director | Revenues falling short of projections. |

| Maine | Press reports on Revenue Forecasting Committee report | |

| Maryland | Maryland Budget and Tax Policy Center | Gap will occur if $500 million in spending cuts assumed in special session bill are not enacted in budget. About $350 million of cuts were specified. The rest are at the discretion of the governor. |

| Massachusetts | Executive Office of Administration and Finance | |

| Michigan | Michigan League for Human Services | |

| Minnesota | Minnesota Department of Finance | |

| Missouri | Missouri Budget Project | |

| Nevada | Press reports of governor’s budget staff projections | |

| New Jersey | Press reports | |

| New York | Division of Budget | |

| Oklahoma | Community Action Project | |

| Ohio | The Center for Community Solutions | |

| Rhode Island | Revenue Estimating Conference | |

| South Carolina | Revenue Forecasting Council | Revenues falling short of projections. |

| Texas | Center for Public Policy Priorities | |

| Vermont | Public Assets Institute | |

| Virginia | Commonwealth Institute | |

| Wisconsin | Legislative Fiscal Bureau | |

End Notes

[1] Nicholas Johnson and Brian Filipowich, “Tax Cuts and Continued Consequences,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 19, 2006.

[2] Michigan continues to feel the effect of significant tax cuts it made in the 1990s, which put the Single Business Tax on a path to elimination and sharply cut the personal income tax. In 2007 the state adopted a revised business tax as a replacement for the Single Business Tax; it also raised income taxes to close a large deficit and adopted a business tax surcharge. Despite this, revenues are still substantially lower than they would have been in the absence of the earlier tax cuts. Moreover, the increases enacted in 2007 are temporary.

[3] Virginia has both cut and raised taxes in recent years. In the 1990s, the state cut the personal property tax on cars — a major revenue source for local governments — but the state reimbursed local governments for the lost revenue. More recently, Virginia raised the sales tax and other taxes, though these tax increases were not enough to offset the impact of the earlier tax cuts on state revenue.

[4] Nicholas Johnson and Sarah Farkas, “Tax Cuts on Layaway,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 10, 2006.

[5] New York enacted a significant property tax relief program that is being phased in through FY2010.

[6] Iris J. Lav, Elizabeth McNichol, and Robert Zahradnik, “https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/5-17-05sfp.pdf,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 2005.

[7] Securitization in this context refers to “selling” a revenue stream (such as the payments to a state from the national tobacco settlement) to a private entity. This gives the state a one-time, up-front payment in place of an ongoing series of annual payments.

[8] Elizabeth McNichol and Brian Filipowich, “Rainy Day Funds: Opportunities for Reform,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised April 17, 2007.

More from the Authors