BEYOND THE NUMBERS

President Trump’s 2018 budget reportedly includes more than $1 trillion in cuts over the next decade to “mandatory” programs that help struggling families afford basics like food and health care; assist people with disabilities and their families; or supplement the earnings of low-income working families. With that in mind, let’s look at the facts about mandatory programs (those funded outside the annual appropriations process):

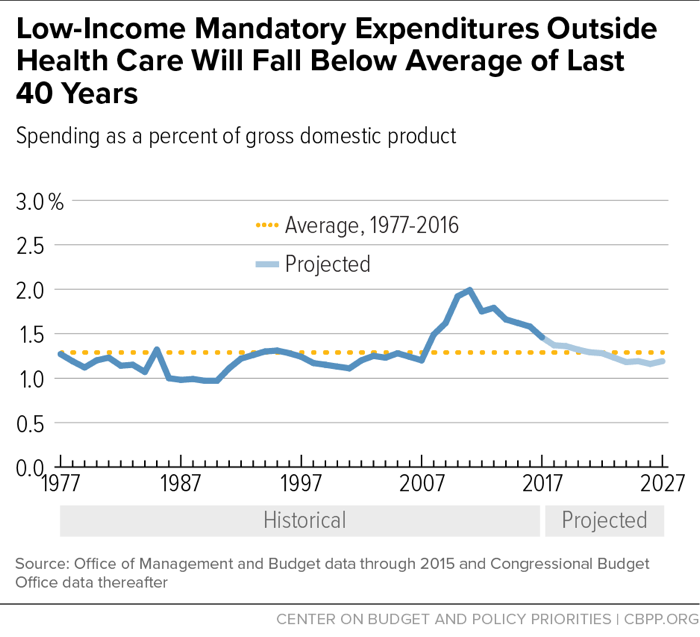

Total spending for mandatory federal low-income programs outside health care is only modestly above its average over the past 40 years, measured as a share of gross domestic product (GDP). And it’s projected to fall as a share of GDP in the future (see graph). Programs that aren’t growing faster than the economy aren’t fueling our long-term fiscal problem.

To be sure, Medicaid is slated to grow faster than GDP. But that’s due to the aging of the population, which will make more seniors (who have higher health care costs) eligible for Medicaid, and to rising costs throughout the U.S. health care system, which partly reflect medical advances that improve health and save lives but add to costs. In fact, Medicaid costs far less per beneficiary than private health insurance, and its costs are rising more slowly. Thus, Medicaid is actually the health insurance system’s most economical and efficient part.

Critics often cite the spending growth in these areas over the past decade to justify large cuts, but the decade really consists of two very different periods. Mandatory spending for low-income programs outside health care — including on SNAP (formerly food stamps) and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) — rose from 1.2 percent of GDP in 2007 to 2.0 percent of GDP in 2011. This reflected increased need during the Great Recession — the worst recession since the Great Depression — and policies adopted in response. It also reflected expansions of the EITC and Child Tax Credit to help low-wage workers better provide for their families.

But as the economy has improved, this spending has dropped significantly since 2011 and is expected to equal 1.5 percent of GDP this fiscal year. (It’s fallen in inflation-adjusted terms as well since 2011.) As one illustration of this pattern, the number of SNAP participants has fallen by 5.5 million since peaking in December 2012. Mandatory spending on low-income programs outside of health is projected to return to the prior 40-year average of 1.3 percent in 2020 and then to fall below the historical average in 2024.

Spending on Medicaid and other low-income health care programs also followed this pattern through 2014: rising during the Great Recession, then starting to fall. This spending then rose in 2015 as the Affordable Care Act provided health coverage to millions of households, producing historic progress in reducing the number of uninsured.

Lower unemployment and higher earnings have recently started significantly reducing the number of people in poverty, but many working families continue to struggle with low earnings, as President Trump himself points out. This means that many families continue to need assistance to afford the basics.

Recent and future trends in spending on mandatory programs thus don’t justify the cuts the Trump budget proposes, particularly since the President has also said he’ll advance large tax cuts — which would primarily benefit high-income people. If deficit reduction is the goal, surely a more balanced approach would make more sense.