BEYOND THE NUMBERS

This month marks 50 years since the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program was signed into law. SSI was initially intended to help prevent people with disabilities and older adults from living in poverty. But due to woefully outdated benefits and rules, the program not only fails to provide enough benefits to lift its beneficiaries living independently above the poverty line, it penalizes work, savings, and receipt of Social Security and other benefits, effectively keeping many beneficiaries in poverty. In the upcoming lame-duck session, policymakers should pass a bipartisan bill to increase SSI’s asset limits — a step toward providing low-income elderly or disabled people with the assistance they need and deserve.

SSI is crucial for its 7.6 million beneficiaries who are disabled or elderly and have little income and few assets; more than half of SSI beneficiaries have no other source of income. SSI reduces hardship for beneficiaries and lessens the need for support from family members and others

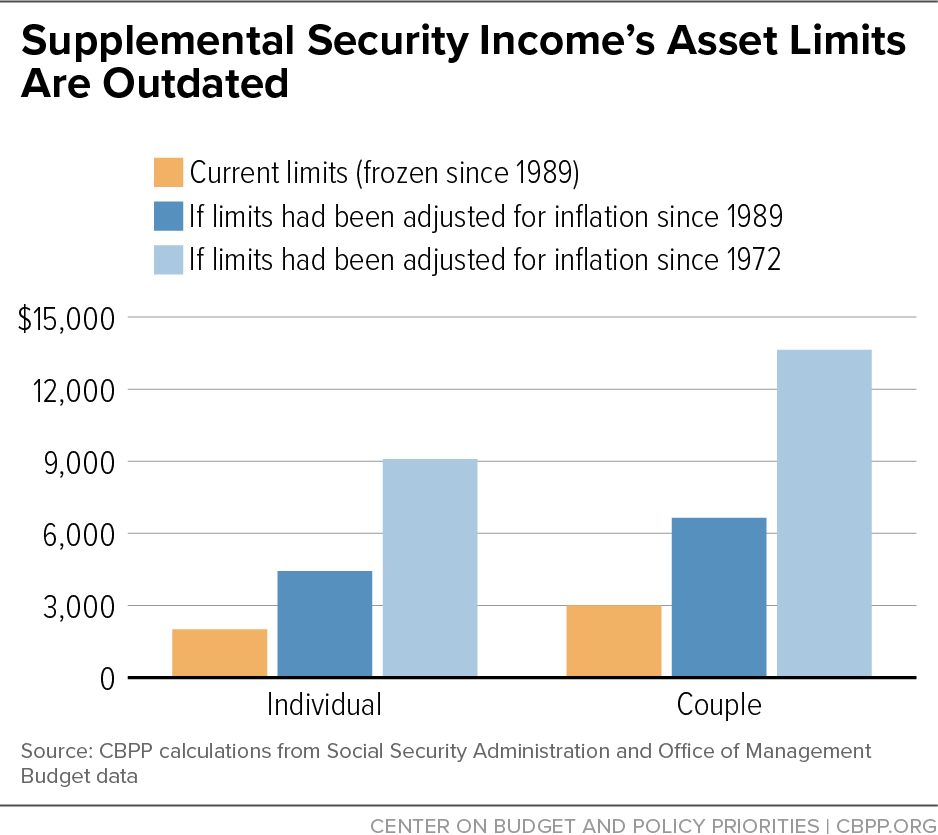

SSI’s asset limits have been frozen since 1989. Beneficiaries can keep $2,000 in savings — far less than what people need to weather emergencies, let alone provide stability for themselves and their families or invest in their futures. Had SSI’s asset limits been indexed since 1972, when the law first passed, they’d be more than four times as high (see chart). Further, the limits erode more in value each year due to inflation, effectively forcing beneficiaries to save less every year. When the rules regarding savings were established in 1972, Individual Retirement Arrangements and 401(k) plans did not yet exist. So while workers today are expected to save for their retirements, SSI beneficiaries are penalized for doing so.

Under the program’s income disregards, beneficiaries who work can keep only $65 of their earnings each month, after which benefits are reduced by $1 for every $2 earned. Those reductions apply even when working beneficiaries’ total incomes are below the poverty line, which penalizes work and keeps working beneficiaries in poverty.

SSI’s treatment of unearned income allows beneficiaries to keep only $20 of most of their other income, such as veteran’s benefits, after which their SSI benefits are reduced dollar-for-dollar. This also includes Social Security benefits, which one-third of SSI beneficiaries receive. On paper, the Social Security benefits average about $570 per month, but SSI beneficiaries may only keep $20 of their Social Security without a reduction in their SSI benefits.

SSI’s “in-kind support and maintenance” rules are also outdated. They require beneficiaries to disclose any material help they receive from family and friends. Each $1 worth of assistance shrinks SSI benefits by $1. No other federal program counts in-kind support when determining eligibility or benefit levels.

Further, SSI’s rules penalize beneficiaries who marry one another. They receive lower benefits and have a lower asset limit than if they remained unmarried. Under the marriage penalty, their asset limit decreases by 25 percent, from $4,000 for two single individuals ($2,000 per individual) to $3,000 for a married couple. And their monthly maximum federal benefit decreases by 25 percent, from $1,682 for two individuals ($841 per individual) to $1,261 for a married couple in 2022.

If the rules governing assets, earnings, and in-kind support are modernized, SSI would make fewer payment errors and be less burdensome for both beneficiaries and administrators. SSI overpayments occur most frequently when beneficiaries’ savings are above the $2,000 asset limit; when their wages exceed $65 in a month; and when they receive in-kind support from family and friends. All of these factors can affect a beneficiary’s eligibility and benefit amount; if the limits were set at more reasonable levels, fewer beneficiaries would exceed them.

These complex and intrusive rules also make SSI more expensive to administer. Administration of SSI benefits requires 35 percent of the Social Security Administration’s (SSA) budget. In contrast, 20 percent of SSA’s budget goes toward administering Social Security’s disability insurance benefits, even though nearly 1.5 million more people receive those benefits compared to SSI.

SSI’s antiquated rules particularly affect communities of color, who make up most of SSI’s beneficiaries. Due to long-standing oppression, including systematic barriers to health care, employment, and other racial and ethnic discrimination, people of color are likelier to live with disabilities, have incomes below the poverty line, and meet SSI’s medical and financial requirements. Improving SSI is a targeted, cost-efficient way to address the hardship stemming from these inequities.

Policymakers have an important opportunity this year to update SSI, ensuring that low-income seniors and people with disabilities have the resources they need to afford rent, food, and other basic needs. Senators Sherrod Brown and Rob Portman’s bipartisan bill to increase SSI asset limits would be a first step toward this goal by allowing beneficiaries to save for emergencies and improve their economic security. It would also reduce administrative burdens, help streamline the application process, and reduce payment errors and program churn.