BEYOND THE NUMBERS

CBO: Senate Bill Would Raise Premiums, Deductibles, or Both for Most Marketplace Consumers

Hoping to deflect concerns about the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) estimate that the Senate’s Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) would cause 22 million people to lose health coverage, its defenders are arguing — as they did with the House-passed health bill — that CBO has at least shown the bill would reduce marketplace premiums. For example, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell released a statement saying that CBO “confirmed” the bill would “reduce the growth in premiums under Obamacare.” In making these claims, the bill’s defenders are either mischaracterizing or misunderstanding what CBO says — which is that most marketplace consumers would pay more in premiums, deductibles, or both, with older consumers facing the highest cost increases. And in many cases, they’d be buying insurance that covered fewer benefits and offered fewer protections.

CBO shows that a typical, middle-aged marketplace consumer would face either higher premiums or higher deductibles. CBO offers the example of a 40-year-old with an annual income of $26,500 — in other words, someone at about the middle of the income and age distribution for someone buying marketplace coverage. Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), CBO estimates that individual would face “sticker price” premiums of about $6,500 for a so-called “silver plan,” which (with the benefit of cost-sharing subsidies) would have annual deductibles of about $800. After tax credits, that person would pay only $1,700 in net premiums.

Under the BCRA, that person would have a choice:

- Continue to buy a silver plan — in which case the sticker price premium would drop by $100, but their tax credit would fall by $1,400. In total, they would pay $1,300 more in premiums to stay in a silver plan — and their deductible would still rise by $2,800 due to the elimination of cost-sharing subsidies.

- Buy a skimpier “bronze” plan — in which case the sticker price premium would fall by $1,500 but their tax credit would fall by $1,400, for net premium savings of just $100. And in return, they would face a much higher deductible of $6,000 a year.

So technically, the sticker price premium numbers would fall in either case. But in reality, this consumer would pay $1,300 more in premiums and see their deductible spike by $2,800, or they would pay about the same in premiums and see their deductible spike by $5,200.

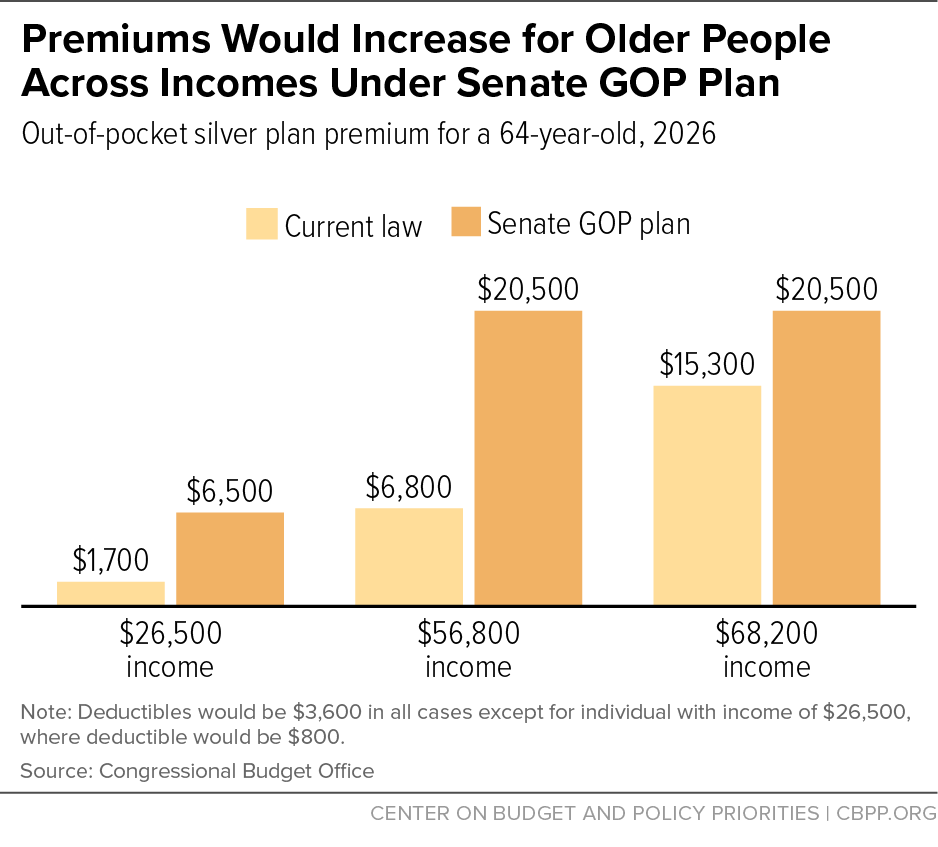

The Senate bill would be even worse for older people. Consider 64-year-olds at three different income levels (see chart).

- For a 64-year-old making $26,500 a year, any option would involve both higher net premiums and deductibles. The choice would be between paying $4,800 more in premiums with $2,800 higher deductibles for a silver plan, or $300 more in premiums with $5,200 higher deductibles for a bronze plan.

- For a 64-year-old making $56,200 a year, costs would rise the most, as he or she would no longer be eligible for a tax credit. That would mean paying either $13,700 more in out-of-pocket premiums to see deductibles stay the same, or paying $9,200 more and seeing deductibles rise by $2,400.

- Even a 64-year-old making $68,200 a year — who doesn’t get tax credits under current law — would be worse off under the Senate bill, as they would either see their premiums rise by $5,200 to pay the same deductibles or pay $700 higher premiums with deductibles rising $700.

Low-income people — many of whom would lose Medicaid coverage — would have access to insurance in name only. For low-income Americans, the Senate bill would effectively end the ACA’s Medicaid expansion — which has provided quality coverage for 11 million newly eligible low-income Americans — and fuel additional eligibility cuts through the Medicaid per capita cap while providing access to tax credits to buy insurance. In practice, as CBO makes clear, it would be access in name only: “[E]ven with the net premium of $300 shown in the illustrative examples for a person with income at 75 percent of the [federal poverty level] ($11,400 in 2026), the deductible would be more than half their annual income. The net premium of a silver plan for a 40-year-old would be about 15 percent of their annual income, and the deductible would be more than one-third of their annual income.” CBO anticipates that among those losing coverage due to the end of Medicaid expansion, “because of the expense for premiums and the high deductibles, most… would not purchase insurance,” meaning that they would become uninsured.

A minority of consumers would be better off, but their gains would be limited. Some marketplace consumers would be better off under the Senate plan — mainly younger, healthy people with higher incomes. But these “winners” would generally see modest benefits compared to what losers would lose: 40-year-olds making $56,800 or $68,200 a year would see premiums for higher-quality silver plans drop by only $100, while 21-year-olds at these income levels would benefit slightly more with premiums dropping by about $1,000 a year.

All the while, people would be buying worse insurance — leaving many people without coverage for essential benefits or facing annual or lifetime coverage limits. Importantly, CBO also emphasizes that the quality of insurance that people buy could be substantially worse. In about half the country, CBO anticipates that states would apply for federal waivers that would let insurers offer plans that don’t cover or severely limit coverage of certain “Essential Health Benefits” (EHBs). CBO writes that: “if the EHBs were modified to drop coverage of services that have high costs and are used by few people, coverage for maternity care, mental health care, rehabilitative and habilitative treatment, and certain very expensive drugs could be at risk.” Previously, CBO noted that supplementary coverage for maternity care, for example, could cost well over $1,000 a month.

CBO also makes clear that these EHB waivers mean that “some enrollees could see large increases in out-of-pocket spending because annual or lifetime limits would be allowed.” As a recent Brookings Institution analysis showed, under the Senate bill, plans could return to imposing annual or lifetime limits on coverage for people receiving insurance through their employers, as well as for those in the individual market.