BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Similar to its estimates of the House-passed bill, the Senate Republican health bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would cause 22 million people to lose coverage by 2026 and drive $772 billion in federal Medicaid cuts over the next ten years, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) found today. This means the bill would result in nearly the same number of people losing their health insurance coverage as under the House-passed bill. It also means that the bill would reverse all of the historic coverage gains achieved since the ACA was enacted in 2010.

The bill — known as the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 (BCRA) — would effectively end the ACA’s Medicaid expansion starting in 2021 and radically restructure Medicaid by converting virtually the entire program to a per capita cap starting in 2020. It would also sharply cut the ACA’s marketplace tax credits and subsidies in 2020 and immediately end the ACA’s individual and employer mandates to buy and provide health coverage, respectively. The Senate bill would require insurers to impose a six-month waiting period on individuals who don’t maintain continuous coverage. It would also permit states to obtain waivers to eliminate the ACA requirement that insurers cover essential health benefits like prescription drugs and mental health treatment, which would also allow the return of annual and lifetime coverage limits. The bill would also drop the bar against insurers charging older people more than three times what they charge younger people.

Among CBO’s key findings:

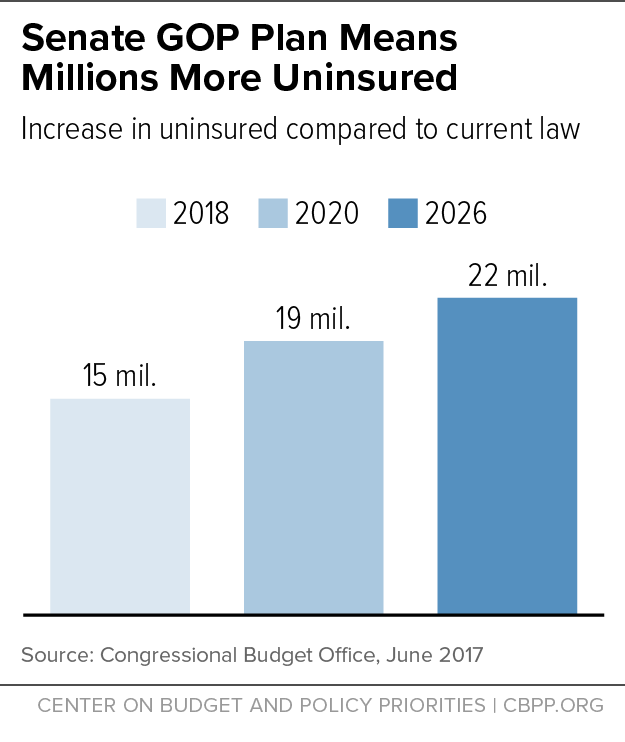

- In 2018, the number of uninsured would rise by 15 million, relative to current law. That number would further rise to 19 million by 2020. By 2026, the number of uninsured would increase by 22 million — or 75 percent higher than under current law (see first chart, below). This means that, by 2026, the historic coverage gains achieved under the ACA would be eliminated and the resulting uninsured rate among the non-elderly would be the same as the 2010 level. According to CBO, like with the House bill, the increase in the number of uninsured would be disproportionately larger among people aged 55-64 with income less than 200 percent of the federal poverty line.

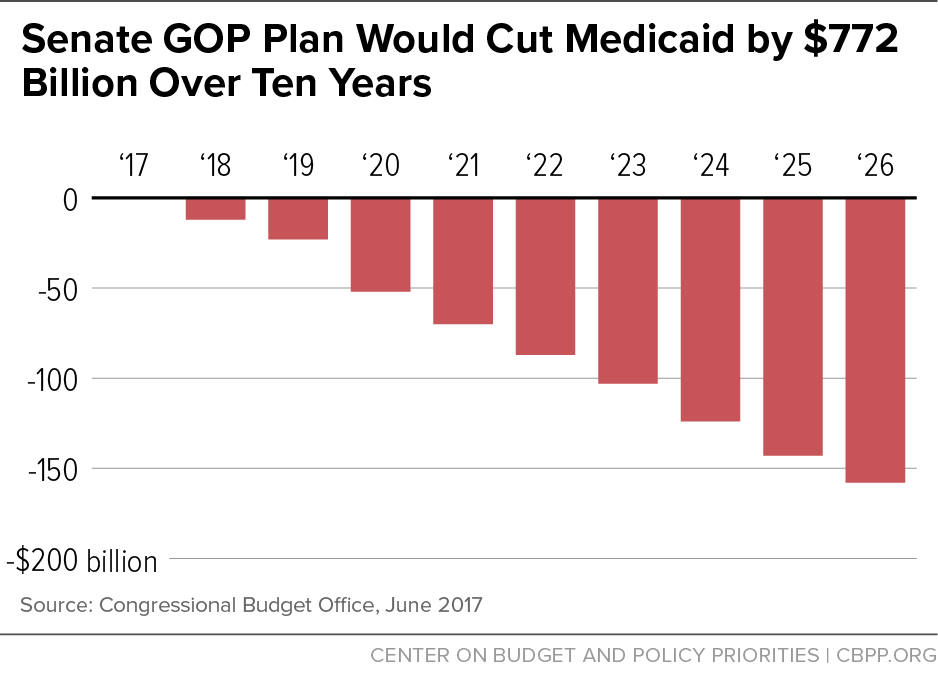

- Federal Medicaid spending would be cut by $772 billion or 15 percent over the next ten years, relative to current law, due to the effective elimination of the Medicaid expansion starting in 2021 and conversion of Medicaid to a per capita cap starting in 2020. (States would also have the option of a Medicaid block grant for non-expansion adults.) By 2026, the annual cut in federal spending would rise to $158 billion, a reduction of 25 percent, relative to current law (see second chart, below). That’s actually $8 billion larger than even under the House bill, likely largely because the Senate bill further lowers the growth rate for federal funding under the per capita cap to general inflation starting in 2025, even below the House bill’s already inadequate level. As a result, the number of Medicaid beneficiaries would fall by 15 million in 2026, or 1 million more than under the House bill.

As the per capita cap cuts become ever larger, CBO expects after 2026 that “enrollment in Medicaid would continue to fall relative to what would happen under current law.” Most of those losing Medicaid would likely end up uninsured. As CBO notes, while “those people would instead be eligible for a premium tax credit under this legislation … because of the expense for premiums and the high deductibles most of them would not purchase insurance….”

- Marketplace enrollees receiving subsidies would face significantly higher premiums and other out-of-pocket costs. Today, premium tax credits are based on the value of “silver plan” coverage: coverage with a 70 percent actuarial value. Under the Senate bill, tax credits would instead be based on the cost of a plan with an actuarial value of 58 percent — roughly equivalent to current “bronze plan” coverage. This would mean much higher deductibles: in 2016, the median deductible for bronze plans was about twice as high as the median deductible for silver plans — $6,300 versus $3,000. As a result, according to CBO, “despite being eligible for premium tax credits, few low-income people would purchase any plan….”

The bill also rearranges the current tax credit schedule, generally reducing premium tax credits for older people while increasing them for younger people. And it eliminates tax credits entirely for people with incomes between 350 percent and 400 percent of the poverty line — about $42,000 to $48,000 for a single person. For example, according to CBO, a 64-year-old with income at 375 percent of the federal poverty line would have to pay $13,700 more in premiums in 2026 for a silver plan because he would no longer be eligible for financial assistance.

Finally, like the House bill, the Senate bill would eliminate the ACA’s cost-sharing subsidies, which help lower deductibles and copayments for low-income marketplace enrollees, and would not replace them. This means that the typical deductible would jump from about $500 to $6,300 for people with incomes between 150 percent and 200 percent of the federal poverty line. As CBO notes, for a person with income at 75 percent of the federal poverty line, the deductible would be more than half his annual income.

- Today’s estimate confirms that older low-income individuals would be particularly hard hit. CBO finds that a typical 64-year-old with income at 175 percent of the federal poverty line would pay in 2026, on average, $4,800 more in premiums in 2026 than under current law to purchase a silver plan, while also having to pay thousands of dollars more in deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs because he would no longer be eligible for cost-sharing reductions.

Notably, CBO’s estimates focus on the average impact nationwide and do not take into account how residents of high-cost states would experience even larger, unaffordable increases in their premiums and other out-of-pocket costs. That’s because the across-the-board cuts to the premium tax credits would be larger in these states than in other states. In states where health costs — and hence premiums — are high, the difference in premiums between more and less generous coverage also is greater.

- CBO estimates that states with about half of the nation’s population would take up “section 1332” waivers that the Senate bill would dramatically expand, primarily to eliminate or weaken the ACA requirement that insurers cover essential health benefits. This, in turn, would lower the premium subsidies that would otherwise be spent, with states using these “pass-through” savings to help stabilize the health insurance market or provide subsidies in different ways. In a small fraction of the affected population, these changes would actually result in fewer people insured because subsidies would be redirected to individuals who would otherwise already purchase coverage or to purposes other than health insurance coverage.

As CBO noted in its earlier analysis of the House-passed bill, people living in such states could experience “substantial increases in out-of-pocket spending on health care or would choose to forgo the services” entirely. Such excluded services would include: maternity care, mental health and substance use disorder treatment, rehabilitative and habilitative services, and pediatric dental care. CBO notes that out-of-pocket costs associated with maternity care and mental health and substance abuse services could increase “by thousands of dollars” and that annual and lifetime limits on benefits would also no longer apply.

Those with the greatest health care needs would see their out-of-pocket payments rise the most in states that eliminated or substantially altered the essential health benefits requirement.

- Overall premiums in the individual market would rise by 20 percent in 2018 and 10 percent in 2019, relative to current law, due to the immediate repeal of the individual mandate as fewer healthy, lower-cost people enroll. In addition, total individual market enrollment would shrink by 7 million in these years. Moreover, after 2019, CBO expects that a fraction of the population will reside in areas where no insurers participated in the individual market or the only insurance available charged very high premiums. This would be due to both the reduction in the subsidies and the deterioration of the risk pool as fewer healthy people enrolled.