BEYOND THE NUMBERS

4 Reasons Why Disability Insurance Is Especially Important to Less-Educated Workers

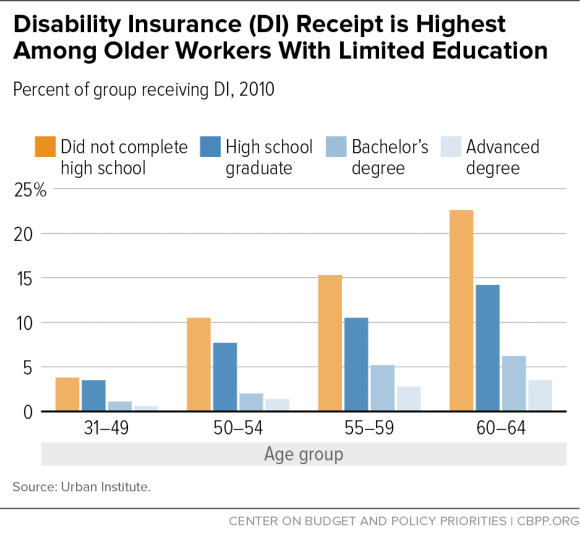

Social Security Disability Insurance (DI) — which pays modest but vital benefits to people with severe and long-lasting medical impairments who can no longer support themselves by working — is especially important to workers who’ve earned only a high-school diploma, or less (see graph). New research has identified several reasons why this group is far likelier to receive DI benefits than those who’ve gone to college.

The new paper, by three top economists with the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), summarizes four major reasons why less-educated workers are likelier to collect DI.

- Poorer health. Less-educated workers consistently report worse health than workers with more education — and poor health was by far the strongest predictor of subsequent DI receipt. The links between education and health are complex, encompassing factors like smoking, obesity, knowledge about health risks and ability to comply with complex care regimens, access to health insurance, and so forth. For many of the same reasons, education is also linked to longer life.

- Lower wealth. Differences in wealth between less- and more-educated workers are even starker than in health. Wealth isn’t directly tied to DI eligibility, but it may serve as a buffer for people who suffer health shocks, and its absence is harrowing for those at the economic margins.

- Blue-collar work. People with less education often work in blue-collar jobs — which are often associated with heavy physical demands or challenging conditions like outdoor toil, exposure to hazardous substances, noisy conditions, and so forth. And people with limited education can’t readily switch to more sedentary work — a reality that the Social Security Administration recognizes in its vocational criteria.

- Employment. People must have a strong work history to qualify for DI — but their ability to work falters as their disability worsens. Less-educated workers are less likely to be employed shortly before qualifying for DI than their better-educated peers, possibly because they can no longer do their old job, and they struggle to find another.

These associations help to explain why DI receipt varies geographically and is highest in areas with lower educational attainment.

In good news, the authors note that overall educational attainment is rising; there will be fewer high-school dropouts, and more college graduates, in the future pool of workers who might qualify for DI. But they also find distressing signs that health and wealth gaps by level of education are widening, not shrinking.

This new paper buttresses a point we’ve made elsewhere: that government benefits such as Social Security, refundable tax credits, and health insurance under the Affordable Care Act are disproportionately important to working-class adults who lack college degrees.